1. Overview

Pontiac or Obwaandi'eyaagObwaandi'eyaagotw (c. 1714/20 - April 20, 1769) was an Odawa war chief who became a prominent leader in the indigenous resistance movement against British colonial expansion in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War. His pivotal role in the conflict, which became known as Pontiac's War (1763-1766), stemmed from widespread Native American dissatisfaction with new British policies regarding trade, land, and overall treatment. While early 19th-century accounts often portrayed Pontiac as the singular mastermind behind the uprising, modern historical scholarship generally views him as an important local leader who influenced and helped spread a wider, decentralized resistance movement rather than commanding it entirely. His actions significantly contributed to the British Crown's issuance of the Proclamation of 1763, an attempt to regulate colonial settlement and preserve Native American territories. Pontiac's legacy continues to be debated and commemorated, reflecting his complex role as a symbol of indigenous autonomy and resistance.

2. Early Life and Background

Pontiac was born between 1712 and 1725, with some sources suggesting his birth around 1714, possibly in an Odawa village situated near the Detroit River or Maumee River. The city of Defiance, Ohio also identifies a park at the confluence of the Maumee and Auglaise rivers as his birthplace. His birth name was ObwandiyagObwandiyagotw, which later evolved into "Pontiac" through English pronunciation of "Bwondiac" in the 19th century.

Historians remain uncertain about the specific tribal affiliations of both his parents. According to an 18th-century Odawa tradition, his mother was a Chippewa (or Ojibwe) and his father an Odawa. However, some accounts propose that one of his parents may have been from the Miami people, or even that Pontiac was born a Catawba and subsequently adopted into the Odawa tribe after being taken captive. Despite these variations, Pontiac was consistently identified as Odawa by those who knew him. Since 1723, he lived in close proximity to Fort Detroit, a location that would later become central to his leadership. Pontiac married a woman named Kantuckee Gun in 1716, and they had two sons. They also had a daughter, Marie Manon, who was described as a Salteuse or Saulteaux Indian and is buried in Assumption Cemetery in Windsor, Ontario.

3. Tribal Leadership and Early Alliances

By 1747, Pontiac had risen to prominence as a war leader among the Odawa people. In this role, he formed an alliance with New France to counter a resistance movement led by Nicholas Orontony, a Huron leader. Orontony had permitted the English to construct a trading post, Fort Sandusky, near Sandusky Bay in Ohio Country in 1745, which Pontiac and his allies opposed.

Pontiac continued to lend his support to the French during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), a conflict against British colonists and their Native American allies. Although direct evidence is lacking, he may have participated in the notable French and Indian victory over the Braddock Expedition on July 9, 1755. His involvement in forming a tribal alliance, including the Odawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe, further solidified his standing as a significant figure in inter-tribal politics.

In 1760, Robert Rogers, a renowned British frontier soldier, claimed to have met Pontiac, though the details of Rogers' account are largely considered unreliable by historians. Nevertheless, Rogers' play, Ponteach: or the Savages of America (1765), played a significant role in elevating Pontiac's fame and contributed to the early mythologizing surrounding him, making him, according to historian Richard White, "the most famous Indian of the eighteenth century."

4. Pontiac's War (1763-1766)

Pontiac's War was a major indigenous resistance movement that erupted in the Great Lakes region and Ohio Valley following the French and Indian War, driven by deep-seated grievances against British policies.

4.1. Background and Causes

The French and Indian War, which concluded in 1760 with the British conquest of Quebec, marked the defeat of New France and fundamentally altered the balance of power in North America. This shift led to widespread discontent among Native American allies of the defeated French. British trading practices became a major point of contention, diverging sharply from the previous French customs. For instance, General Jeffery Amherst, the architect of British Indian policy, ordered the construction of Fort Sandusky in 1761 on the south shore of Sandusky Bay, despite treaty assurances that the British would not build forts in Ohio Country.

Amherst further aggravated Native American nations by cutting back on the practice of giving customary gifts, which the French had provided but Amherst considered mere bribes. He also restricted the distribution of essential supplies such as gunpowder and ammunition, which indigenous peoples relied on for hunting. Many Native Americans believed that these British policies were aimed at subjugating or even destroying them. Following the war, British colonists began entering lands previously under French influence, leading to increased land encroachment.

This growing anti-British sentiment was significantly amplified by a religious revival movement spearheaded by Neolin, a Lenape prophet. Neolin preached a message of rejecting European cultural influences and returning to traditional indigenous ways of life. Pontiac, likely already involved in a nascent resistance, attended a 1762 conference on the Detroit River where leaders reportedly issued a call to arms to various tribes, solidifying his role as part of a broader movement for indigenous sovereignty. Pontiac's strong desire for the French to return was so profound that he initially refused to believe that France had truly conceded the territory, viewing it as a British deception.

4.2. Planning and Initial Uprising

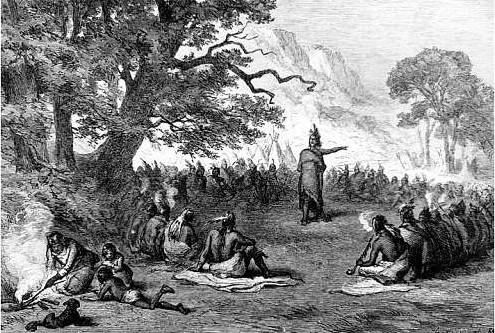

On April 27, 1763, Pontiac convened a large council approximately 10 mile (9.9 mile (16 km)) below Fort Detroit in present-day Council Point Park in Lincoln Park, Michigan. At this gathering, Pontiac passionately urged his listeners to unite and launch a surprise attack on Fort Detroit. To assess the garrison's strength, Pontiac visited the fort on May 1 with 50 Odawa warriors, gathering crucial intelligence for the planned assault.

According to a French chronicler, Pontiac delivered a powerful speech at a second council, articulating the motivations for the uprising:

"It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see as well as I that we can no longer supply our needs, as we have done from our brothers, the French.... Therefore, my brothers, we must all swear their destruction and wait no longer. Nothing prevents us; they are few in numbers, and we can accomplish it. The French are all subdued, But who are in their Stead become our Lords? A proud, imperious, churlish, haughty Band. The French familiarized themselves with us, Studied our Tongue, and Manners, wore our Dress, Married our Daughters, and our Sons their Maids, Dealt honestly, and well supplied our Wants, Used no one ill, and treated with Respect Our Kings, our Captains, and our aged Men; Call'd us their Friends, nay, what is more, their Children. And seem'd like Fathers anxious for our Welfare."

Pontiac's War officially began on May 7, 1763, when Pontiac and 300 followers attempted to execute their surprise attack on Fort Detroit. However, their plan was thwarted because Major Henry Gladwin, the fort's commander, had received a warning from an informer and had prepared his defenses. With the element of surprise lost, Pontiac was forced to withdraw and seek alternative strategies to capture the fort, though without immediate success.

4.3. Siege of Fort Detroit and Major Engagements

Following the failed surprise attack, Pontiac initiated a prolonged Siege of Fort Detroit on May 9, 1763. His initial 300 followers were soon reinforced by over 900 warriors from half a dozen different tribes, collectively besieging the fort and cutting off its supplies and reinforcements.

Despite the sustained siege, Pontiac and his allied forces faced significant challenges in dislodging the British garrison. A major military confrontation occurred in July 1763, known as the Battle of Bloody Run. In this engagement, Pontiac's forces decisively defeated a British detachment, showcasing the fighting prowess of the allied tribes. However, even with this victory, Pontiac was ultimately unable to capture Fort Detroit. In October 1763, Pontiac decided to lift the siege and strategically withdrew his forces to the Illinois Country, where he had relatives and continued to encourage resistance.

4.4. Spread of the Conflict

While Pontiac was actively besieging Fort Detroit, messengers rapidly spread word of his actions and the underlying grievances across the region. This communication catalyzed a widespread uprising that extended far beyond Detroit, transforming local resistance into a broader, decentralized conflict. Native American warriors launched extensive attacks against British forts and Anglo-American settlements throughout the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region. It is important to note that these attacks specifically targeted British and Anglo-American settlements, not those of the French colonists, reflecting the desire to re-establish the French alliance.

During the peak of the conflict, the allied tribes gained control of nine out of eleven British forts in the Ohio Valley. Among their significant victories was the destruction of Fort Sandusky. This widespread success demonstrated the remarkable coordination and determination of the diverse Native American nations, despite operating without a single centralized command structure. Tribal leaders around Fort Pitt and Fort Niagara, for example, had already been advocating for war against the British independently, further illustrating the broad and decentralized nature of this indigenous resistance movement.

4.5. Consequences and Resolution

After the failure of the extended siege of Fort Detroit, the British initially believed that Pontiac's influence was waning and that the uprising was effectively quelled. However, Pontiac continued to actively encourage militant resistance among the Illinois and Wabash tribes, and he also sought to recruit French colonists as allies. This period saw Pontiac exert his greatest influence, evolving from a local war leader into a significant regional spokesman for the Native American cause.

Recognizing the tenuous nature of their military dominance despite pacifying some areas, the British decided to enter into negotiations with the Odawa leader. By making Pontiac the central figure of their diplomatic efforts, the British inadvertently elevated his stature, often misinterpreting the decentralized nature of Native American warfare and leadership. On July 25, 1766, Pontiac formally met with Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, at Fort Ontario in Oswego, New York. During this meeting, Pontiac signed a peace treaty, officially ending hostilities and bringing the rebellions to a close.

The aftermath of Pontiac's War led to an ironic outcome: to prevent similar uprisings, the British significantly increased their frontier presence in the years following the conflict, directly opposing Pontiac's original intentions of removing them. Perhaps most notably, Pontiac's War represents the final major indigenous rebellions against British control in the Ohio Country before the formation of the United States. While the war did not result in the full expulsion of the British, it underscored the resilience of Native American resistance and compelled the British Crown to issue the Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains to preserve an area for Native Americans. This policy, though not fully enforced, acknowledged Native American land rights and was a direct consequence of the widespread indigenous resistance.

5. Later Life and Diplomacy

Pontiac's final years saw a shifting landscape of influence and diplomatic engagements. The significant attention and recognition afforded to him by the British Crown following the war, while perhaps intended to facilitate peace, inadvertently encouraged him to exert a level of power among the regional Native American nations that exceeded traditional tribal rights. Historian Richard White noted that "By 1766 he was acting arrogantly and imperiously," assuming authorities that no other Western Indian leader typically possessed. This perceived overreach contributed to his increasing ostracization among some tribal leaders, who traditionally operated within a consensus-based system where chiefs were mediators rather than absolute commanders.

In 1768, as a consequence of these shifting dynamics and possibly declining local support, Pontiac was compelled to leave his Odawa village on the Maumee River. He relocated to an area near Ouiatenon on the Wabash River. On May 10, 1768, in a significant indicator of his altered standing, he dictated a letter to British officials explicitly stating that he was no longer recognized as a chief by the people of his former village on the Maumee. Despite this localized decline, he continued to be seen as a key figure by the British, who had made him the focus of their post-war diplomatic efforts.

6. Ideology and Resistance

Pontiac's resistance against British colonial rule was deeply rooted in a philosophical and cultural ideology that advocated for the preservation of indigenous ways of life and a rejection of European cultural influences. Central to his thinking was the message of the Lenape prophet Neolin, who called for Native Americans to return to traditional practices and resist the assimilation pressures of European presence.

Pontiac strongly believed that the British sought to subjugate or even destroy Native American nations, contrasting their policies with the earlier, more amicable relationship the French had cultivated through trade and respect for indigenous customs. His desire to see the French return was so profound that he initially disbelieved reports of their defeat, viewing it as a British ploy to further their agenda. Pontiac's primary objective was to eliminate British forts and settlers from Native American lands, thereby restoring the friendly and beneficial trade relations that had existed with the French. This vision of indigenous self-determination and the removal of the British was a unifying force for many tribes during Pontiac's War, highlighting his role not just as a military strategist, but as a proponent of cultural and political autonomy.

7. Personal Life

Pontiac's personal life is sparsely documented in historical records, though some details offer a glimpse into his family. He was married to a woman named Kantuckee Gun in 1716. Together, they had two sons. Additionally, Pontiac had a daughter named Marie Manon, who was identified as a Salteuse or Saulteaux Indian. Marie Manon is buried in Assumption Cemetery in Windsor, Ontario, Canada. While his public life was dominated by his military and diplomatic roles, these familial connections underscore his grounding within the social fabric of his Odawa community.

8. Assassination

Pontiac was assassinated on April 20, 1769. The killing occurred near the French town of Cahokia, Illinois, although some accounts suggest it took place in a nearby Native American village. His killer was an unnamed Peoria warrior, whose motive was to avenge his uncle, a Peoria chief named Makachinga (also known as Black Dog). Pontiac had reportedly stabbed and severely wounded Makachinga in 1766. A Peoria band council had, in fact, authorized Pontiac's execution. The Peoria warrior approached Pontiac from behind, stunned him with a club, and then stabbed him to death.

Following his death, various rumors circulated about the circumstances, including unfounded claims that the British had hired his assassin. Early historical narratives, such as those by Benjamin Drake in 1848, suggest a widespread retaliatory war against the Peoria and other bands of the Illinois Confederation by an alliance of other tribes, leading to the near-destruction of the Illinois Confederation. Lieutenant Pike, in his travels, also noted that Pontiac's killing sparked a devastating war. However, modern historians largely dispute the existence of a widespread "terrible war of retaliation" as depicted by Francis Parkman in The Conspiracy of Pontiac (1851), finding no evidence of such extensive Native American reprisals for his murder.

Pontiac's exact burial place remains unknown. While some speculate he was buried at Cahokia, evidence and tradition suggest his body was taken across the Mississippi River and interred in St. Louis, a town recently founded by French colonists. In 1900, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a commemorative plaque at the southeast corner of Walnut and South Broadway in St. Louis, indicating a location believed to be near his burial site.

9. Historical Assessment and Legacy

Pontiac's historical significance has been a subject of evolving interpretation, reflecting changes in scholarly understanding of Native American leadership and the complexities of colonial conflicts. His legacy is also visibly commemorated through various place names and other cultural references.

9.1. Historical Interpretations

Early historical accounts of Pontiac's War, particularly from the 19th century, frequently portrayed Pontiac as a singular, ruthless yet brilliant mastermind orchestrating a vast "conspiracy." For instance, Norman Barton Wood famously dubbed him the "Red Napoleon." These interpretations often attributed an almost singular authority to Pontiac, envisioning him as the absolute commander of the entire Native American resistance.

However, contemporary historians generally offer a more nuanced perspective. They agree that Pontiac's actions at Detroit were indeed a crucial spark that instigated the widespread uprising. Furthermore, he played a significant role in expanding the resistance by dispatching emissaries who urged other leaders to join the cause. Despite this, modern scholarship emphasizes that Pontiac did not command the various tribal war leaders as a unified entity. Instead, the diverse Native American groups operated in a highly decentralized manner, with their own leaders independently deciding to engage in resistance. Indian societies, unlike European hierarchies, typically relied on consensus and shared leadership, where a chief served more as a mediator and influential figure rather than an absolute ruler. This contrasts with the British assumption that Native American chiefs wielded more centralized authority than they typically did, leading to their focus on Pontiac in diplomatic efforts.

Historian John Sugden summarizes this view, stating that Pontiac "was neither the originator nor the strategist of the rebellion, but he kindled it by daring to act, and his early successes, ambition, and determination won him a temporary prominence not enjoyed by any of the other Indian leaders." This understanding highlights Pontiac's role as a key local catalyst and a highly influential figure within a broader, multi-tribal movement, rather than its sole commander.

9.2. Criticisms and Controversies

One notable controversy associated with Pontiac involves the alleged killing of Elizabeth "Betty" Fisher, a seven-year-old English colonist. In 1763, during the Siege of Detroit, an Odawa war party attacked the Fisher farm, resulting in the death of Betty's parents and her capture. The following year, while Betty was held captive at Pontiac's village, she became ill with dysentery. According to court testimony, Pontiac became enraged when the girl soiled some of his clothes while trying to warm herself by his fire. He reportedly picked up the naked child, threw her into the Maumee River, and instructed a French-speaking ally to wade into the river and drown her, which was carried out. The French colonist involved was later arrested by the British but had escaped by the time Pontiac was summoned to Detroit in August 1767 to testify in the murder investigation. Pontiac neither confirmed nor denied his role in the incident, and the investigation was eventually dropped. This event is cited by critics as an example of brutality during the conflict, though historical context regarding the widespread violence and tensions of the war period is also considered.

9.3. Legacy and Commemoration

Pontiac's name and image continue to resonate in contemporary culture and geography. Several places across North America are named in his honor, including the cities of Pontiac, Michigan and Pontiac, Illinois in the United States, as well as Pontiac, Quebec, and the Pontiac Regional County Municipality in Canada.

His name also became synonymous with a popular American automobile brand, Pontiac, manufactured by General Motors. The brand, originally based in Detroit, utilized an image of Pontiac in its first logo in 1926 before its discontinuation in 2010. Additionally, a Belgian watch company was reportedly named after him, inspired by a legend that he could tell time by the stars. Numerous streets, buildings, and other public landmarks throughout the United States also bear Pontiac's name, cementing his place in historical memory as a significant figure in Native American resistance.

10. Related Topics

- Pontiac's War

- French and Indian War

- Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst

- Neolin

- William Johnson, 1st Baronet