1. Overview

Field Marshal Jeffery Amherst (1717-1797) was a prominent British Army officer and Commander-in-Chief credited with orchestrating Britain's successful conquest of New France during the Seven Years' War. Under his command, British forces captured pivotal cities and fortresses, including Louisbourg, Quebec City, and Montreal, effectively ending French rule in North America. He subsequently served as the first British Governor-General in the territories that later became Canada.

Despite his significant military achievements, Amherst's legacy is marked by profound controversy, particularly concerning his policies towards North American Native Americans. His actions, including his explicit advocacy for the use of smallpox-infected blankets against disaffected tribes during Pontiac's War, have led to severe criticism and an ongoing reassessment of his historical role. This aspect of his career reflects a deeply troubling disregard for indigenous lives, which, from a center-left perspective, highlights a darker side of colonial expansion and warfare. Consequently, numerous places and institutions previously named in his honor have been renamed or are undergoing reevaluation, acknowledging the suffering caused by his policies and promoting reconciliation.

2. Early Life and Military Beginnings

Jeffery Amherst's early life laid the foundation for a distinguished, yet controversial, military career within the British Army, beginning with a traditional upbringing in Kent and progressing rapidly through the ranks.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Jeffery Amherst was born in Sevenoaks, England, on 29 January 1717. He was the son of Jeffrey Amherst, a lawyer from Kent, and Elizabeth Amherst (née Kerrill). From an early age, he served as a page to the Duke of Dorset, a position that likely offered him an early introduction to prominent social and political circles.

2.2. Early Military Service

Amherst began his military career at the age of 14, joining the army as an ensign in the Grenadier Guards in 1735. His early service included participation in the War of the Austrian Succession, where he served as an aide to General John Ligonier. During this conflict, he saw action at the Battle of Dettingen in June 1743 and the Battle of Fontenoy in May 1745. Demonstrating early promise, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 25 December 1745 and later participated in the Battle of Rocoux in October 1746. He subsequently became an aide to the Duke of Cumberland, then commander of British forces, and saw further combat at the Battle of Lauffeld in July 1747.

3. Seven Years' War and North American Conquest

Amherst gained widespread fame during the Seven Years' War, particularly for his pivotal role in the North American theater, often referred to as the French and Indian War, which culminated in the end of French colonial power in the region.

3.1. German Front

In February 1756, Amherst was appointed commissar to the Hessian forces, which were assembled to defend Hanover as part of the Army of Observation. With a French invasion of Britain appearing imminent, Amherst was tasked in April with arranging the transportation of thousands of German troops to southern England to bolster Britain's defenses. He was made colonel of the 15th Regiment of Foot on 12 June 1756.

By 1757, as the immediate threat to Britain subsided, these troops were moved back to Hanover to join a growing allied army under the Duke of Cumberland. Amherst fought alongside the Hessians under Cumberland's command at the Battle of Hastenbeck in July 1757. The allied defeat there forced the army into a steady retreat northward to Stade, near the North Sea coast. This retreat and the subsequent Convention of Klosterzeven, where Hanover agreed to withdraw from the war, left Amherst dispirited. He began preparations to disband his Hessian troops, only for the convention to be repudiated and the allied force reformed, allowing the campaign to continue.

3.2. French and Indian War

Amherst's significant contributions to the Seven Years' War were predominantly made in North America during what is known as the French and Indian War. His leadership as commander-in-chief of British forces proved decisive in dismantling French colonial power.

In June 1758, he led the successful attack on Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, a critical French fortress. Following this victory, he was appointed commander-in-chief of the British army in North America and colonel-in-chief of the 60th (Royal American) Regiment in September 1758.

Under his command, several key objectives were achieved. In July 1759, Amherst led an army against French forces on Lake Champlain, successfully capturing Fort Ticonderoga. Concurrently, another British force under William Johnson captured Fort Niagara in the same month. Further bolstering British gains, James Wolfe besieged and ultimately captured Quebec City with a third army in September 1759. Amherst also served as the nominal Crown Governor of Virginia from 12 September 1759.

From July 1760, Amherst embarked on a major offensive down the Saint Lawrence River from Fort Oswego. He orchestrated a three-pronged attack, joining forces with Brigadier Murray from Quebec and Brigadier Haviland from Ile-aux-Noix. This coordinated effort culminated in the capture of Montreal on 8 September 1760, effectively ending French rule in North America. Amherst's refusal to grant the French commanders the honours of war infuriated them, leading the Chevalier de Lévis to burn the French colours rather than surrender them.

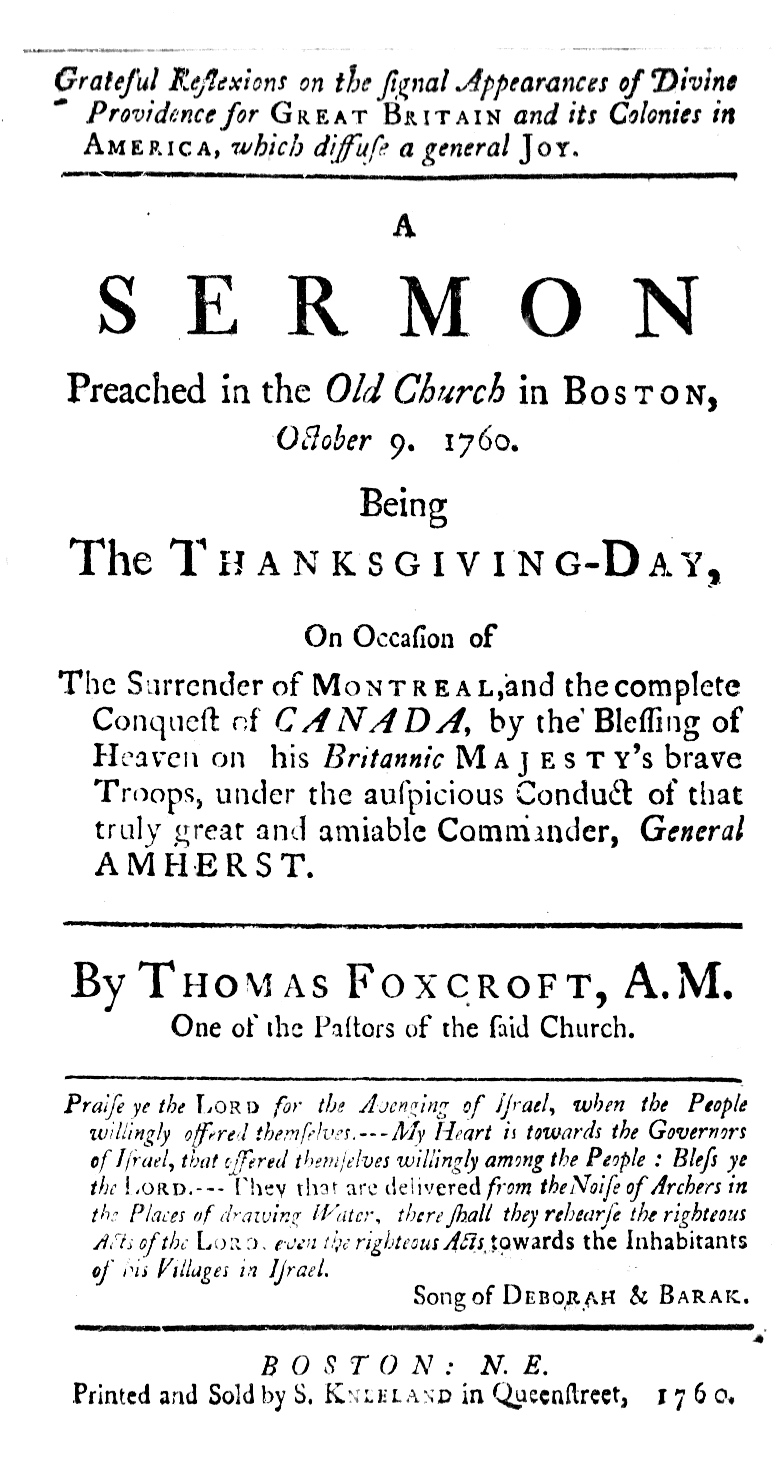

The British settlers greeted this victory with immense relief, proclaiming a day of thanksgiving. Boston newspapers of the time describe celebrations with parades, a grand dinner in Faneuil Hall, music, bonfires, and cannon fire. The Reverend Thomas Foxcroft of the First Church in Boston encapsulated the sentiment, stating, "The Lord hath done great things for us, whereof we are glad... Canada must be conquered, or we could hope for no lasting quiet in these parts; and now, through the good hand of our God upon us, we see the happy day of its accomplishment."

In recognition of these decisive victories, Amherst was appointed the first Governor-General of British North America in September 1760 and was promoted to major-general on 29 November 1760. He was also appointed a Knight of the Order of the Bath on 11 April 1761. From his base in New York, Amherst oversaw the dispatch of troops under Monckton and Haviland to participate in British expeditions in the West Indies, which resulted in the capture of Dominica in 1761 and Martinique and Cuba in 1762.

3.2.1. Key Battles and Victories

Jeffery Amherst's command during the French and Indian War was characterized by a series of strategically important sieges and campaigns that led to decisive British victories.

- Siege of Louisbourg (1758)**: Amherst led the British attack on the formidable French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island in June 1758. The successful siege and capture of Louisbourg were crucial as it secured a vital gateway to the Saint Lawrence River and effectively opened the way for British advances into the heart of New France. French forces, numbering six battalions, surrendered on 26 July 1758.

- Battle of Fort Niagara (1759)**: While not directly commanded by Amherst, the capture of Fort Niagara in July 1759 by a British force under William Johnson was part of the larger strategic offensive orchestrated under Amherst's overall command. This victory cut off French communication and supply lines between Canada and their western territories, significantly weakening their position. Fort Duquesne also fell on 24 November 1758, further eroding French control.

- Capture of Fort Ticonderoga (1759)**: In July 1759, Amherst led his army against French troops on Lake Champlain, where he successfully captured Fort Ticonderoga. This strategic stronghold provided a key position for further British incursions into French territory. Crown Point also fell on 4 August 1759.

- Montreal Campaign (1760)**: Amherst spearheaded the final campaign against Montreal. Beginning in July 1760, he led an army down the Saint Lawrence River from Fort Oswego, coordinating a complex three-way pincer movement with forces led by Brigadier Murray from Quebec and Brigadier Haviland from Île-aux-Noix. This comprehensive campaign resulted in the capture of Montreal on 8 September 1760, compelling the surrender of French forces, including ten battalions, and marking the conclusive end of French colonial rule in North America. Further gains included the surrender of Fort Lévis on 25 August 1760 and the abandonment of Île-aux-Noix on 28 August 1760. Beyond North America, the British also recaptured St. John's, Newfoundland, on 18 September 1762, solidifying their control over key strategic locations.

4. Colonial Administration and Post-War Governance

Following his military triumphs in the French and Indian War, Jeffery Amherst transitioned into administrative roles, overseeing the newly acquired British territories in North America.

4.1. Governor of Virginia Colony

Jeffery Amherst held the nominal title of Crown Governor of Virginia from 12 September 1759 until 1768. However, his duties as Commander-in-Chief in North America kept him occupied elsewhere, meaning he was largely an absentee governor. During this period, the administration of the colony was effectively managed by Francis Fauquier, who served as the acting governor.

4.2. Governor-General of British North America

In September 1760, in recognition of his significant military achievements, Amherst was appointed the first Governor-General of British North America. This role placed him in charge of governing the vast newly acquired territories previously under French control. He served in this capacity until 1763, overseeing the initial integration of these lands into the British colonial system. From his headquarters in New York, he continued to direct military operations, including the dispatch of troops under commanders like Monckton and Haviland to British expeditions in the West Indies. These expeditions resulted in the British capture of Dominica in 1761 and subsequently Martinique and Cuba in 1762, expanding British imperial reach.

5. Pontiac's War and Controversy

The period following the French and Indian War saw escalating tensions between the British and Native American tribes, culminating in Pontiac's War, a conflict that profoundly tarnished Amherst's legacy due to his controversial policies and actions, particularly regarding biological warfare.

5.1. Background and Native American Policy

The defeat of France in North America removed a crucial counterbalance to British expansion, leading to increased British territorial ambitions and a shift in policy towards Native Americans. From 1753, when the French first ventured into the territory, until February 1763, when peace was formally declared between the English and French, the Six Nations and their allied tribes consistently maintained that both the French and British should remain east of the Allegheny Mountains. However, the British failed to honor their previous agreements to withdraw from the Ohio Valley and Allegheny valleys after the war, instead beginning to occupy former French forts and expand their presence.

This perceived betrayal and the imposition of restrictive new policies, including the cessation of gift-giving and controls on trade, fueled deep resentment among indigenous peoples. In response to what they saw as an invasion of their lands and a threat to their way of life, a loose confederation of Native American tribes, including the Delawares, Shawnees, Senecas, Mingoes, Mohicans, Miamis, Ottawas, and Wyandots, banded together. Their collective goal was to drive the British out of their ancestral territories, leading to the outbreak of Pontiac's War in early 1763, named after one of its most prominent leaders, Pontiac. Jeffery Amherst's inability to comprehend and respect the customs and rights of Native Americans, coupled with his aggressive and exclusionary policies, was a direct cause of the widespread indigenous resistance.

5.2. Smallpox Blanket Incident

One of the most infamous and widely debated aspects of Jeffery Amherst's legacy involves the proposal and alleged use of smallpox-infected blankets against Native Americans during Pontiac's War, highlighting the ethical depth of his command decisions.

During the Siege of Fort Pitt in June 1763, Colonel Henry Bouquet, the commander of Fort Pitt, and Captain Simeon Ecuyer, without Amherst's prior knowledge of this specific action, made the decision to give smallpox-infected items to Native American representatives. During a parley on 24 June 1763, Ecuyer provided two blankets and a handkerchief, which had been exposed to smallpox, to representatives of the besieging Delawares. The intent was explicitly to spread the disease to end the siege. William Trent, a trader turned militia commander who conceived the plan, later sent an invoice to British colonial authorities for the blankets, explicitly stating their purpose was "to Convey the Smallpox to the Indians." This invoice was subsequently approved by Thomas Gage, who was then serving as Commander-in-Chief, North America. Trent's personal report on the parleys stated: "[We] gave them two Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Small Pox Hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect." Military hospital records further confirm that two blankets and handkerchiefs were "taken from people in the Hospital to Convey the Smallpox to the Indians."

A month later, after learning that smallpox had broken out among the garrison at Fort Pitt and following the loss of other British forts, Amherst himself discussed the use of smallpox blankets in correspondence with Colonel Bouquet. On 16 July 1763, Amherst wrote to Bouquet: "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them."

Bouquet, who was already marching to relieve Fort Pitt, explicitly agreed with Amherst's suggestion in a postscript to his response on 13 July 1763: "P.S. I will try to inoculate - the Indians by means of Blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself. As it is pity to oppose good men against them, I wish we could make use of the Spaniard's Method, and hunt them with English Dogs. Supported by Rangers, and some Light Horse, who would I think effectively extirpate or remove that Vermine."

Amherst's reply, also in a postscript, on 16 July, further cemented his endorsement of these brutal tactics: "P.S. You will Do well to try to Innoculate - the Indians by means of Blankets, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race. I should be very glad your Scheme for Hunting them Down by Dogs could take Effect, but England is at too great a Distance to think of that at present."

While a reported smallpox outbreak in the Ohio Country from 1763 to 1764 resulted in the deaths of as many as one hundred Native Americans, it remains historically debated whether this outbreak was a direct result of the Fort Pitt incident or if the virus was already circulating among the Delaware people, as outbreaks occurred every dozen years or so. Furthermore, subsequent encounters with the Native American delegates who received the blankets showed no clear signs of them contracting the disease. Contemporary scientific understanding also suggests that the transmission of smallpox through fomites (like blankets) is much less efficient than respiratory transmission, and scabs from smallpox patients have low infectivity. Regardless of the immediate efficacy or direct causation, the correspondence unequivocally documents the intent of top British military officials, including Amherst, to engage in biological warfare and to pursue the "extirpation" of Native American populations, marking a deeply disturbing chapter in British colonial history.

5.3. Aftermath and Recall

Following Pontiac's War, Jeffery Amherst was summoned back to Britain. Although ostensibly recalled for consultations on future military strategies in North America, his return also served as an accountability measure for the recent Native American rebellion. Contrary to his expectation of praise for the conquest of Canada, Amherst found himself pressured to defend his conduct and policies. He faced significant criticism from influential figures such as William Johnson and George Croghan, who actively lobbied the Board of Trade for his removal and permanent replacement by Thomas Gage. Furthermore, he received severe criticism from military subordinates on both sides of the Atlantic, questioning his leadership during the conflict.

Despite these criticisms, Amherst continued to advance in the British military hierarchy. He was promoted to lieutenant-general on 26 March 1765. In November 1768, he became the colonel of the 3rd Regiment of Foot. On 22 October 1772, he was appointed Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, a significant position through which he soon gained the confidence of George III, who had initially hoped the role would go to a member of the Royal Family. Amherst was subsequently made a member of the Privy Council on 6 November 1772.

6. Later Life and Activities in Britain

After his recall from North America, Jeffery Amherst continued to play significant military and political roles in Britain, especially during periods of domestic unrest and international conflict, though his later tenures were met with mixed reception.

6.1. First Tenure as Commander-in-Chief

On 14 May 1776, Jeffery Amherst was elevated to the peerage as Baron Amherst, of Holmesdale in the County of Kent. Two years later, on 24 March 1778, he was promoted to the rank of full general. In April 1778, he attained the prestigious position of Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, granting him a seat in the Cabinet.

During this period, as the American Revolutionary War escalated, Amherst was considered by the government as a potential replacement for William Howe, the British commander in North America, who had requested to be relieved. However, Amherst's insistence that it would require 75,000 troops to fully suppress the American rebellion was deemed unacceptable by the government, leading to Henry Clinton being chosen instead. Following the British setback at the Battle of Saratoga, Amherst successfully advocated for a more limited war strategy in North America. This approach focused on maintaining strategic footholds along the coast, defending Canada, East and West Florida, and the West Indies, while shifting greater emphasis to naval warfare. In a sign of royal favor, King George III and Queen Charlotte visited Amherst at his home, Montreal Park, in Kent on 7 November 1778. On 24 April 1779, he became colonel of the 2nd Troop of Horse Grenadier Guards.

6.2. American War of Independence and Home Defense

Beyond his strategic advice regarding the American War of Independence, Jeffery Amherst played a critical role in organizing Britain's home defenses. A long-standing plan by the French, which gained momentum when Spain entered the war in 1779, involved a potential invasion of Great Britain. The increasingly depleted state of British home forces made such an invasion more appealing to the Bourbon powers. In anticipation of this threat, Amherst meticulously organized Britain's land defenses to counter the planned invasion by the Armada of 1779, which ultimately never materialized. His efforts were crucial in ensuring the preparedness of the home front against external threats during a period of significant international conflict.

6.3. Suppression of the Gordon Riots

In June 1780, Jeffery Amherst was tasked with overseeing the British army's response to the Gordon Riots, a series of severe anti-Catholic uprisings in London. He deployed the small London garrison of Horse and Foot Guards as effectively as possible. However, his efforts were significantly hindered by the reluctance of the civil magistrates to authorize decisive action against the rioters, a common challenge in military interventions during civil unrest.

Line troops and militia were brought in from surrounding counties, increasing the forces under Amherst's command to over 15,000 soldiers, many of whom were quartered in tents in Hyde Park. A form of martial law was declared, granting troops the authority to open fire on crowds, but only after the Riot Act had been formally read. Although order was eventually restored, Amherst was personally alarmed by the authorities' initial failure to swiftly suppress the riots, highlighting the complexities and dangers of deploying military forces in civil disturbances.

6.4. Second Tenure as Commander-in-Chief and Criticisms

In the wake of the Gordon Riots, Amherst was compelled to resign as Commander-in-Chief in February 1782, being replaced by Henry Conway. On 23 March 1782, he became captain and colonel of the 2nd Troop of Horse Guards. His career continued to evolve; on 8 July 1788, he became colonel of the 2nd Regiment of Life Guards. Further recognition came on 30 August 1788, when he was created Baron Amherst, this time with the territorial designation of Montreal in the County of Kent. This new title included a special provision allowing it to pass to his nephew, William Pitt Amherst, as Jeffery Amherst had no children, ensuring the continuity of the peerage after the Holmesdale title became extinct upon his death.

With the advent of the French Revolutionary Wars, Amherst was recalled to serve a second tenure as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in January 1793. However, this period of his leadership is generally criticized for allowing the British armed forces to fall into a state of acute decline, which contributed directly to the failures of the early campaigns in the Low Countries. Prominent figures of the time voiced strong disapproval of his performance. Pitt the Younger remarked that Amherst's "age, and perhaps his natural temper, are little suited to the activity and the energy which the present moment calls for." Likewise, Horace Walpole scornfully referred to him as "that log of wood whose stupidity and incapacity are past belief." His critics further lamented that he "allowed innumerable abuses to grow up in the army," and "kept his command, though almost in his dotage, with a tenacity that cannot be too much censured." This period saw his reputation suffer due to perceived mismanagement and a lack of vigor in preparing the army for the new European conflicts.

6.5. Family and Death

Jeffery Amherst was married twice but had no children from either marriage. In 1753, he married Jane Dalison (1723-1765). Following her death, he married Elizabeth Cary (1740-1830), the daughter of Lieutenant General George Cary, on 26 March 1767. Elizabeth later became Lady Amherst of Holmesdale.

He retired from his second tenure as Commander-in-Chief in February 1795, succeeded by the Duke of York. His final promotion came on 30 July 1796, when he was advanced to the rank of field marshal. Jeffery Amherst retired to his private estate at Montreal Park in Kent, where he died on 3 August 1797. He was buried in the Parish Church at Sevenoaks.

7. Legacy and Historical Assessment

Jeffery Amherst's legacy is complex and highly debated, encompassing both his acclaimed military achievements that expanded the British Empire and the severe criticisms stemming from his policies and expressed desires regarding Native Americans. His historical assessment reflects a stark contrast between colonial-era veneration and modern scrutiny focused on human rights and social justice.

7.1. Places and Institutions Named After Him

Numerous places and institutions across North America and Britain were historically named in honor of Jeffery Amherst, reflecting his significance during the British Empire's expansion. These include:

- Canada**:

- Amherst Island, Ontario

- Amherstburg, Ontario, which is also home to General Amherst High School.

- Amherst, Nova Scotia

- United States**:

- Amherst, Massachusetts, notable for hosting the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Hampshire College, and Amherst College.

- Amherst, New Hampshire

- Amherst, New York

- Amherst County, Virginia

7.2. Controversy and Reassessment

Amherst's legacy is now widely viewed through a critical lens, particularly his explicit desire to exterminate indigenous populations, which is regarded as a dark stain on his historical record. This has prompted significant movements to reconsider and remove his name from public spaces and institutions.

In 2007, "The Un-Canadians," an article in The Beaver, included Amherst in a list of contemptible figures in Canadian history due to his support for distributing smallpox-infected blankets to First Nations people. In 2008, Mi'kmaq spiritual leader John Joe Sark strongly condemned the name of Fort Amherst Park on Prince Edward Island, calling it a "terrible blotch on Canada" and drawing a comparison to naming a city in Jerusalem after Adolf Hitler, emphasizing its deeply offensive nature. Sark reiterated these concerns in a letter to the Canadian government in January 2016. Mi'kmaq historian Daniel N. Paul, who asserts Amherst was motivated by white supremacist beliefs, also supports renaming efforts, arguing that nothing should be named after individuals who committed what can be described as "crimes against humanity." Following a formal request, Parks Canada reviewed the matter. An online petition initiated by Sark in February 2016 further formalized the public's desire for change. Consequently, on 16 February 2018, the site was officially renamed Skmaqn-Port-la-Joye-Fort Amherst, integrating a Mi'kmaq word to acknowledge indigenous heritage.

Similar efforts have taken place in municipal contexts. In 2009, Montreal City Councillor Nicolas Montmorency officially requested that Rue Amherst be renamed, stating it was "totally unacceptable that a man who made comments supporting the extermination of Native Americans to be honoured in this way." On 13 September 2017, the city of Montreal decided to rename the street. On 21 June 2019, it was officially renamed Rue Atateken (Atatekenmeaning "those with whom one shares values"Mohawk). Following this trend, Rue Amherst in Gatineau was also renamed Rue Wìgwàs (Wìgwàsmeaning "white birch"Ojibwa) in 2023.

Academic institutions have also engaged in this reassessment. In 2016, Amherst College controversially dropped its "Lord Jeffery" mascot due to student instigation. Further dissociating from his problematic legacy, the campus hotel, previously known as the Lord Jeffery Inn, was renamed the Inn on Boltwood in early 2019. These actions underscore a broader societal movement towards reconciliation and a critical reevaluation of historical figures whose actions conflict with contemporary human rights values.

7.3. Montreal Park Estate

After his decisive capture of Montreal in 1760, Jeffery Amherst established his primary residence in his hometown of Sevenoaks, Kent, naming it Montreal House, which later became known as Montreal Park. This estate served as his private retreat during his later life in Britain.

Historically, the Montreal Park estate held community significance, particularly from the late 19th to the early 20th century, when the Amherst family hosted annual summer picnics for children graduating from a local primary school they had founded in the nearby village of Riverhead, Kent. This school continues to use the Amherst family crest as its emblem, a lingering connection to the estate's benefactors. However, with the decline of the Amherst family's fortunes in the 20th century, Montreal House was eventually demolished, and the land was redeveloped for residential housing.

Today, tangible remnants of the estate include an obelisk and an octagonal gatehouse, which serve as memorials. The obelisk features an inscription, though now fading, that details Amherst's military campaigns in Canada. The inscription, notably, does not explicitly name Amherst himself, which has been interpreted by some as an act of modesty on his part, or perhaps a reflection of the prevailing assumption that his role in these celebrated victories was self-evident. The inscription lists the following key achievements:

- Commemoration of the divine providence and happiness of three brothers meeting at this ancestral home on 25 January 1761, having served for six years in a glorious war across various climates, seasons, and battles with success.

- Dedicated to the most capable statesman, whose operations led to the conquest of Cape Breton Island and Canada, influencing the British Army to achieve unprecedented glory.

- Louisbourg fortress surrendered with six French battalions, 26 July 1758.

- Fort Duquesne fell, 24 November 1758.

- Fort Niagara surrendered, 25 July 1759.

- Fort Ticonderoga fell, 26 July 1759.

- Crown Point fell, 4 August 1759.

- Quebec City occupied, 18 September 1759.

- Fort Lévis surrendered, 25 August 1760.

- Île-aux-Noix abandoned, 28 August 1760.

- Montreal surrendered, with Canada and ten French battalions laying down arms, 8 September 1760.

- St. John's, Newfoundland, recaptured, 18 September 1762.

8. See also

- John Ligonier, 1st Earl Ligonier

- Prince William, Duke of Cumberland

- Seven Years' War

- French and Indian War

- Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

- Fort Ticonderoga

- Fort Niagara

- Montreal

- James Wolfe

- Thomas Gage

- Pontiac's War

- Smallpox

- Biological warfare

- Gordon Riots

- American Revolutionary War

- Field marshal (United Kingdom)