1. Overview

Piero del Pollaiuolo (Piero del PollaiuoloPYAIR-oh del pol-LY-WOH-lohItalian; born c. 1443, died by 1496), also known as Piero Benci, was an Italian Renaissance painter from Florence. He often collaborated with his older brother, the artist Antonio del Pollaiuolo. While their works reflect classical influences and a deep interest in human anatomy, distinguishing their individual contributions, especially in shared paintings, has historically been a complex challenge for art historians. Early accounts, notably those by Giorgio Vasari, tended to emphasize Antonio's role, overshadowing Piero's individual talent. However, modern scholarship, spearheaded by figures such as Aldo Galli, has led to a significant re-evaluation of Piero's oeuvre, resulting in the re-attribution of many prominent works to him and providing a clearer understanding of his distinct artistic contributions and unique style.

2. Biography

Piero del Pollaiuolo's life was closely intertwined with his family's trades and his artistic collaboration with his older brother, a partnership that largely defined his career.

2.1. Early life and family

Piero del Pollaiuolo was born in Florence around 1443. His birth name was Piero Benci. The surname 'Pollaiuolo' was a nickname derived from his father Jacopo's trade; `pollaioItalian` means "hen coop" in Italian, and `pollaiuoloItalian` signifies a "poulterer." At the time, the poultry trade was considered a luxury business. Jacopo had four sons, and it was unlikely all could find careers within this specific trade. Historical records, such as those from Benedetto Dei, a contemporary Florentine chronicler, indicate that in 1472, Florence had only eight poultry suppliers, contrasting sharply with 44 goldsmiths' workshops, suggesting a competitive environment.

Antonio was the eldest son. The two middle brothers pursued different paths: one eventually inherited the family poultry business, and another became a goldsmith. Piero was the youngest brother, and he and Antonio frequently worked together. Although their workshops were physically separate, they were mutually accessible, facilitating their collaborative efforts.

2.2. Artistic development and collaboration

Piero's artistic training remains somewhat uncertain. The Florentine painter Andrea del Castagno, who died in 1457, has been considered a potential master for both brothers based on stylistic similarities and Vasari's writings. However, dating inconsistencies have led many modern scholars to question this assertion.

The brothers' work distinctly shows both classical influences and a notable interest in human anatomy. According to Vasari, the Pollaiuolo brothers engaged in human dissections to deepen their knowledge of the subject. While this claim has been influential, modern scholars tend to doubt the extent or practicality of such dissections for artists at the time. A surviving letter from Antonio, dated 1494, states that he and a brother (presumed to be Piero) painted three immense canvases depicting the Labours of Hercules for the Medici Palace some 34 years prior. These paintings, renowned in their time, are now lost, but this letter provides rare specific documentation of Antonio's involvement in a painting project, confirming a joint effort. Art historians generally believe Antonio might have misremembered the exact date by a year or two.

A record from Francesco Albertini in 1510 credits Piero alone with painting a six-meter-high fresco of Saint Christopher on the facade of San Miniato fra le Torri, near his residence in Florence. Both the church and the fresco have since disappeared. Albertini also attributed other works, including the *Saint Sebastian* altarpiece (now in London) and the *Cardinal of Portugal's Altarpiece*, solely to Piero.

2.3. Later life and death

Piero del Pollaiuolo's only signed and dated work is the `Coronation of the Virgin`, completed in 1483 for `Sant'Agostino` in `San Gimignano`. Around 1484, when he was about 41 years old, Piero followed Antonio to Rome, and it is believed he spent most of his remaining years there. Not many works are typically attributed to this later Roman period.

The last definitive record of Piero is from November 1485, when he received payment for an unidentified painting in Pistoia Cathedral. His death is confirmed by Antonio's will, dated November 1496, which indicates Piero was already deceased by then. The precise date and circumstances of his death are unknown. Given that his tomb is in Rome, alongside Antonio's, it is presumed he died in the city. Piero never married, but he left an illegitimate daughter named Lisa, whose care was entrusted to Antonio. Antonio later provided 150 ITL for Lisa's dowry when she married.

3. Artistic Contributions

Piero del Pollaiuolo's artistic contributions are marked by both historical ambiguity regarding attribution and a distinct stylistic approach that modern scholarship increasingly recognizes as unique and influential.

3.1. Attribution challenges and re-evaluation

Historically, distinguishing Piero's individual works from those of his elder brother Antonio, or determining the extent of their collaboration, has been a significant challenge. Contemporaries often regarded Antonio as the more accomplished talent, partly because he was also a renowned sculptor, whereas Piero primarily focused on painting. This perception was reinforced by early art historical accounts, most notably Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, written several decades after both brothers' deaths. Vasari emphasized Antonio's prowess in disegno (drawing), suggesting that Antonio likely handled most of the underdrawing for shared works, leaving Piero and their assistants to complete the actual painting. This established a tradition of stressing Antonio's contribution over Piero's in their joint output, a view that largely went unchallenged until the 20th century.

However, suspicions regarding these attributions emerged in the late 19th century from art historians like Crowe and Cavalcaselle and later in the 20th century from Martin Davies, a director of the National Gallery. A full and partly successful re-evaluation has been mounted in the 21st century, significantly altering many traditional attributions. This re-assessment has been primarily led by scholars such as Aldo Galli, whose 2014 work, Antonio and Piero Del Pollaiuolo: Silver and Gold, Painting and Bronze, reassigned the actual painting of numerous works to Piero, which had long been attributed solely to Antonio or to both brothers. This revisionist approach often argues that Piero, rather than Antonio, was influenced by the landscape style of Early Netherlandish painting.

While many works are still given joint attributions, particularly larger pieces, smaller works have frequently been reassigned to a single brother. For example, Apollo and Daphne (c. 1470-1480) in the National Gallery in London was long attributed to Antonio but is now described by the museum as solely by Piero. Similarly, the Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1470) in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan, previously often assigned to Antonio, is now regarded by the museum (which is Galli's institutional base) as by Piero. Other similar portraits in Berlin, the Uffizi in Florence, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York form a group of four often given the same attribution, though the plainer Boston portrait is sometimes separated. The Profile Portrait of a Young Lady in Berlin has been attributed to both brothers individually, as well as to several other masters.

A letter from Antonio in 1494 indicates that the original, large-scale `Three Labours of Hercules` paintings, created for the Medici Palace over 30 years prior and now lost, were a joint work by both brothers. This remains the only specific documentation linking Antonio to any painting project. Galli accepts the traditional attribution of the miniature versions of two of these works, now in the Uffizi, to Antonio.

For the largest surviving Pollaiuolo painting, the `Saint Sebastian` altarpiece (completed 1475), now in the National Gallery, differences in quality within the large painted area have often been noted. Traditionally, the highest-quality parts were attributed to Antonio, with lesser areas assigned to Piero or assistants. However, Galli attributes the entire piece to Piero and his team.

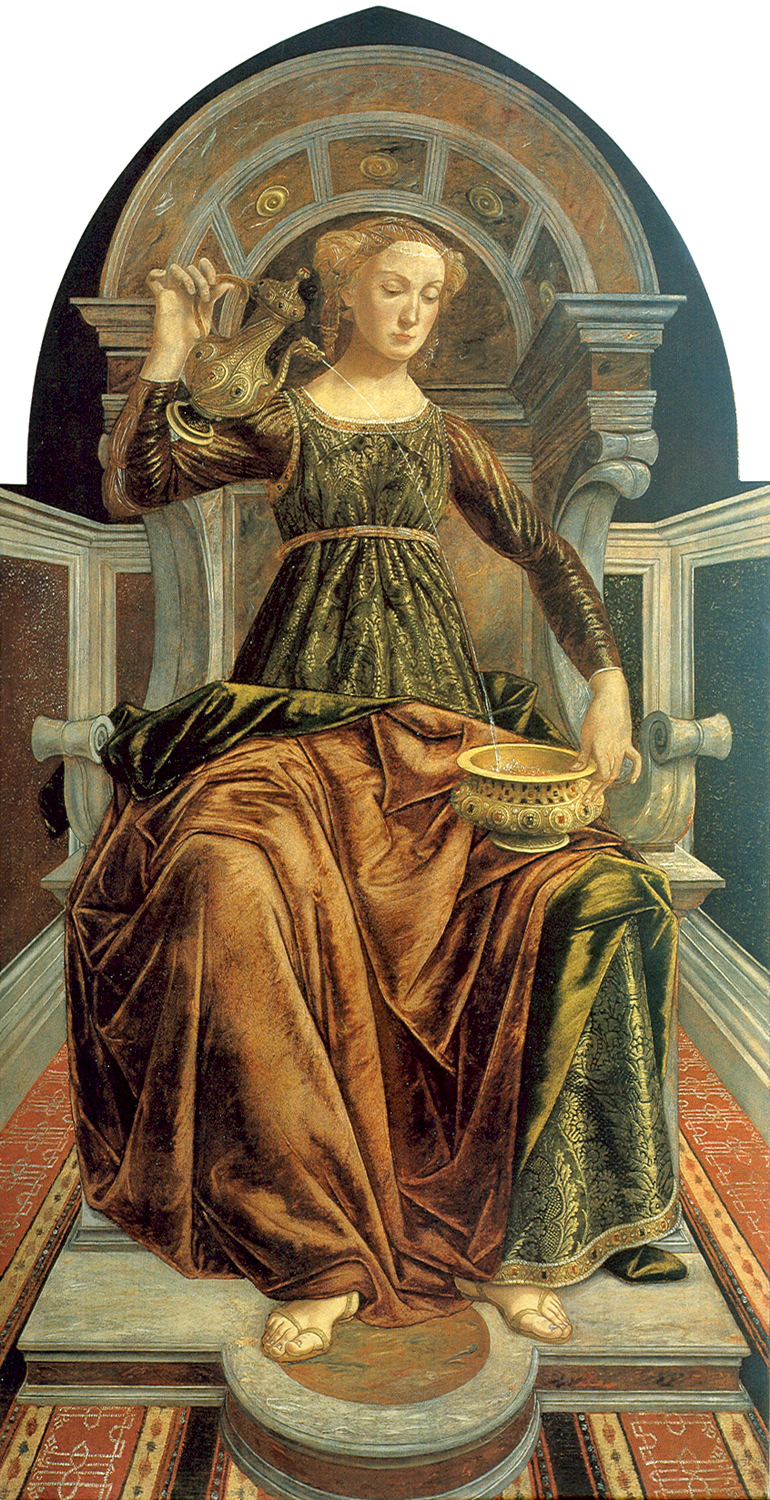

Piero received a significant and highly public commission in 1479 for a series of full-length paintings depicting the Seven Virtues for the Palazzo della Signoria, the seat of government of the Republic of Florence. These works were intended to decorate the room of the `Tribunale della Mercanzia`, the body overseeing all the Guilds of Florence. After some public contention, `Fortitude` was painted by Sandro Botticelli, while Piero completed the other six virtues. All seven are now housed in the Uffizi. Given the brothers' close working relationship, some art historians continue to suggest Antonio's involvement in aspects of these paintings, either in their design or execution, though payments were documented to Piero. Other scholars are content to use the style of these documented works to attribute similar pieces to Piero's workshop.

Aldo Galli's re-attribution of paintings relies not only on stylistic analysis but also on a reassessment of early documentary records predating Vasari, including comments by writers like the `Anonimo Gaddiano` from the 1530s and 1540s. One characteristic and unusual technique attributed to Piero, or sometimes Antonio, is painting directly onto the wood panel without the standard careful preparation of glue and gesso. Examples include the `Lady` in Boston and `Galeazzo Maria Sforza` in the Uffizi. This technique was also seen in the `David` in Berlin, which Galli attributes to Piero, though it was traditionally considered Antonio's.

A recently re-attributed Portrait of a Youth was sold at Sotheby's in 2021 for 4.56 M GBP, equivalent to 6.26 M USD. This was the first "fully attributed work" by Piero to come to auction, having previously been attributed to artists such as Cosimo Rosselli. This portrait, along with that of `Galeazzo Maria Sforza`, constitutes Piero's only known male portraits. The teenage subject is depicted in an almost frontal pose, which was unusual for Florentine portraiture of that period. This re-attribution was supported by leading scholars including Alison Wright and Aldo Galli.

3.2. Style and technique

The characterization of Piero del Pollaiuolo's artistic style is intricately linked to which paintings are attributed to him and his workshop. Earlier critics, such as Wilhelm Bode, complained about what they perceived as arbitrary attributions, especially those influenced by Bernard Berenson, who was particularly dismissive of works he allowed to Piero. Berenson, in 1903, described Piero's `Coronation of the Virgin` in San Gimignano as "a picture of unalloyed mediocrity, with scarcely a touch of charm to repay the absence of life and vigour." Similarly, Frederick Hartt, an admirer of Antonio, labeled Piero "a painter-a dull one, judging by his one signed work."

In stark contrast, Aldo Galli champions the `Coronation of the Virgin` as "a magnificent painting" that exhibits "close stylistic and technical affinities" with other works he attributes to Piero, including the six `Virtues` and the London `Saint Sebastian` altarpiece. According to Galli, these works collectively reveal Piero's distinct style, characterized by "a pronounced taste for precious effects." This includes a "highly efficacious imitation of jewels, brocades, and velvets," achieved through an "illusionistic and tactile treatment" based on the "extensive and experimental use of oil-based binders." This was particularly innovative during a period when tempera was the predominant medium in Florence, and it showcased an "open emulation of the Flemish masters."

Galli further describes Piero's compositions as "highly studied, always somewhat artificial, populated with rather lanky and awkward figures, often seen with bottom-to-top perspective, with hands and feet that are nervously articulated, somewhat affected, emerging in their aristocratic pallor from silks and velvets studded with rubies and gilded trimmings." This "refulgent pictorial treatment" is a hallmark of his approach. The revisionist school of thought, particularly Galli's, suggests that Piero was influenced by the landscape style prevalent in Early Netherlandish painting.

Another notable technical feature of some of Piero's works is that they are painted directly onto the wood panel, deviating from the customary meticulous preparation involving glue and gesso. Examples include the `Lady` in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and `Galeazzo Maria Sforza` in the Uffizi. This technique has also been observed in works previously attributed to Antonio, such as the `David` in Berlin, which Galli now attributes to Piero.

3.3. Major works and commissions

Piero del Pollaiuolo undertook several significant commissions and created influential works throughout his career.

His documented, important, and highly public commission was the series of full-length paintings of the `Seven Virtues` for the `Palazzo della Signoria` between 1469 and 1470. These were intended to decorate the `Tribunale della Mercanzia`. While `Fortitude` was completed by Botticelli, Piero painted the other six virtues: `Charity`, `Faith`, `Temperance`, `Prudence`, `Hope`, and `Justice`. All seven are now housed in the Uffizi.

Piero's only signed and dated work is the `Coronation of the Virgin` (1483), an altarpiece located in `Sant'Agostino`, `San Gimignano`.

Notable works attributed to Piero, with some having undergone significant re-attribution, include:

- Profile Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1465) - oil on wood, Berlin. Often previously attributed to Antonio.

- Tobias and the Angel (c. 1465-1470) - Turin, attributed by the museum to both brothers.

- Cardinal of Portugal's Altarpiece (1467-1468) - altarpiece, long given to Antonio, now in the Uffizi.

- Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1470) - Milan, now attributed to Piero.

- Portrait of a Lady (Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum).

- Apollo and Daphne (c. 1470-1480) - National Gallery, London, now attributed to Piero (formerly often Antonio).

- Portrait of Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1471) - tempera on wood, Uffizi. This work was recorded as by Piero in a 1492 Palazzo Medici inventory and has always been attributed to him, though it is in poor condition. Its turning pose with a visible hand was unusual for Florentine portraiture of the time, potentially influenced by the sitter, the Duke of Milan, who was keenly interested in portraiture.

- Portrait of a Woman (c. 1475) - Uffizi, still attributed to Antonio by the Uffizi as of 2023.

- Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (completed 1475) - oil on wood, National Gallery, London. Long attributed to both brothers by the National Gallery, but Aldo Galli attributes it entirely to Piero and his team.

- Portrait of a Youth - a recently re-attributed male portrait sold at Sotheby's in 2021. The teenage subject is depicted in an almost frontal pose, which was uncommon for the period.

4. Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Piero del Pollaiuolo's enduring legacy in art history has been shaped by a significant re-evaluation of his individual contributions, challenging earlier, more dismissive views.

4.1. Shifting critical reception

For centuries, Piero del Pollaiuolo's artistic merit was often overshadowed by his more celebrated brother, Antonio. Critics like Bernard Berenson were particularly harsh, describing Piero's only signed work, the `Coronation of the Virgin`, as "a picture of unalloyed mediocrity." Frederick Hartt similarly characterized Piero as "a painter-a dull one." This largely negative critical reception persisted, limiting the recognition of his unique artistic voice.

However, the 21st century has witnessed a profound shift in this perception, largely driven by the scholarship of Aldo Galli. Galli and other contemporary art historians have mounted a successful challenge to the traditional narrative, re-attributing numerous significant works to Piero and arguing for a distinct and valuable artistic identity. This modern scholarship re-evaluates Piero's stylistic nuances and technical innovations, such as his experimental use of oil-based binders and his "precious effects" in depicting textures, transforming his once-maligned `Coronation of the Virgin` into a "magnificent painting" within this new framework. This re-appraisal underscores a growing appreciation for Piero's individual contribution and unique aesthetic.

4.2. Influence on art history

The re-assessment of Piero del Pollaiuolo's oeuvre has had a significant impact on the understanding of artistic practice in 15th-century Florence. By disentangling his work from Antonio's and highlighting his distinct stylistic traits and technical preferences, scholars have gained a more refined and nuanced view of the Florentine art scene. Piero's documented commissions, such as the `Seven Virtues`, provide crucial insights into the collaborative dynamics of workshops and the evolving patronage of the period. Furthermore, the identification of his unique approach to materials and his possible influence from Early Netherlandish painting broaden the understanding of cross-cultural artistic exchanges in the Renaissance. His re-emerging standing as a distinct master contributes to a richer and more accurate historical narrative of Florentine painting.