1. Early Life and Education

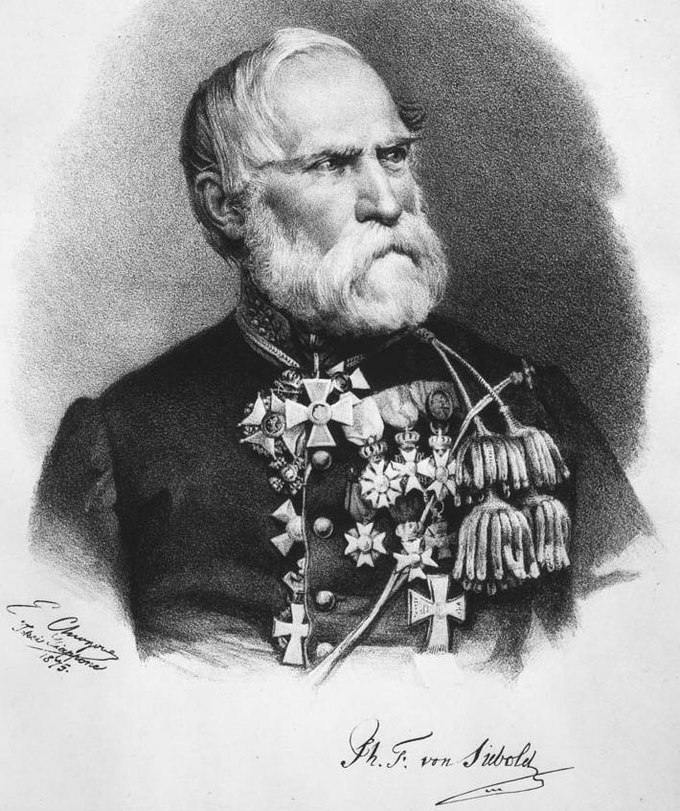

Philipp Franz von Siebold was born on February 17, 1796, in Würzburg, then part of the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg within the Holy Roman Empire (now in Bavaria, Germany). His family was a distinguished lineage of physicians and professors of medicine; his father, Johann Georg Christoph von Siebold, was a professor of obstetrics at University of Würzburg but died when Philipp was only one year and one month old. Philipp was subsequently raised by his maternal uncle in Heidingsfeld, which is now part of Würzburg. The Siebold family was ennobled, adding "von" to their name, and registered into the nobility of the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1816, when Philipp was 20 years old.

He entered the University of Würzburg in November 1815, initially studying philosophy before shifting to medicine, following his family's tradition. During his university years, he resided with his anatomy and physiology professor, Ignaz Döllinger (1770-1841), who profoundly influenced him. Döllinger was one of the first professors to approach medicine as a natural science, fostering an environment where Siebold regularly interacted with other scientists. Siebold was also a member of the Corps Moenania Würzburg, a student fraternity, and served as its chairman. Possessing a strong sense of pride in his noble background, he was known for his high self-esteem and reportedly engaged in 33 duels, leaving scars on his face. His passion for natural science was further ignited by reading the works of renowned naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, which fostered his desire to travel to distant lands.

Siebold received his Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree in 1820 and began his medical practice in Heidingsfeld. His early academic recognitions included being appointed a corresponding member of the Senckenberg Society for Natural Science Research, a member of the Royal Leopold-Caroline Academy of Natural Scientists, and a full member of the Wetterau Natural History Society in 1822. These appointments came with a commission to collect type specimens for a newly established museum in Frankfurt.

2. Assignment to East Asia and First Arrival in Japan

2.1. Activities in the Dutch East Indies

Siebold's ambition to travel to the Dutch colonies led him to apply for a position as a military physician in the Netherlands, after being invited by a family acquaintance. He officially entered Dutch military service on June 19, 1822, and was appointed ship's surgeon aboard the frigate Adriana, which sailed from Rotterdam to Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia). During the five-month voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, he diligently practiced his Dutch and quickly learned Malay, while also commencing a collection of marine fauna.

Upon his arrival in Batavia on February 18, 1823, Siebold was initially assigned to an artillery unit as an army medical officer. However, an illness led him to recover for three weeks at the residence of the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, Baron Godert van der Capellen. His intellectual prowess and erudition deeply impressed Governor-General van der Capellen and Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt, the director of the botanical garden at Buitenzorg (now Bogor). They recognized in Siebold a worthy successor to previous esteemed physicians and botanists who had served at Dejima, the Dutch trading post in Japan, such as Engelbert Kaempfer and Carl Peter Thunberg. In April 1823, Siebold was elected a member of the Batavian Academy of Arts and Sciences. Shortly thereafter, he received a new assignment: to serve as a resident physician and scientist at Dejima in Nagasaki, Japan.

2.2. Arrival and Role in Dejima

Siebold departed Batavia for Dejima on June 28, 1823. His journey was perilous; he narrowly escaped drowning when his ship was struck by a powerful typhoon in the East China Sea. He finally arrived at Dejima, a small artificial island and trading post in Nagasaki, on August 11, 1823. During Japan's period of isolation, the Tokugawa shogunate permitted only a very limited number of Dutch personnel to reside on Dejima. Consequently, Siebold assumed a dual role as both physician and scientist. The European tradition of sending doctors with botanical training to Japan had been established by figures like Engelbert Kaempfer, a German physician and botanist who served in Japan from 1690 to 1692 for the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and Carl Peter Thunberg, a Swedish botanist and physician who arrived in 1775.

Upon his arrival, Siebold's accent in Dutch, which was distinct from that of native Dutch speakers, aroused suspicion among Japanese interpreters. He explained this by claiming to be a "mountain Dutchman" or "highland Dutchman," an explanation that surprisingly appeased the Japanese, who were unaware that the Netherlands was largely flat terrain. Siebold's arrival marked the beginning of his influential period in Japan, during which he became one of the "Three Scholars of Dejima," alongside Kaempfer and Thunberg, despite none of them being ethnically Dutch.

3. Major Activities in Japan (First Stay)

During his initial period in Japan, Siebold engaged in significant medical and scientific endeavors, playing a crucial role in introducing Western knowledge and extensively documenting Japanese natural history and culture.

3.1. Introduction and Education of Western Medicine

Siebold's medical expertise quickly earned him recognition. After successfully treating an influential local officer, he gained unprecedented permission to leave the confines of the Dejima trading post and treat Japanese patients in the surrounding areas of Nagasaki. He is widely credited with introducing vaccination and pathological anatomy to Japan for the first time.

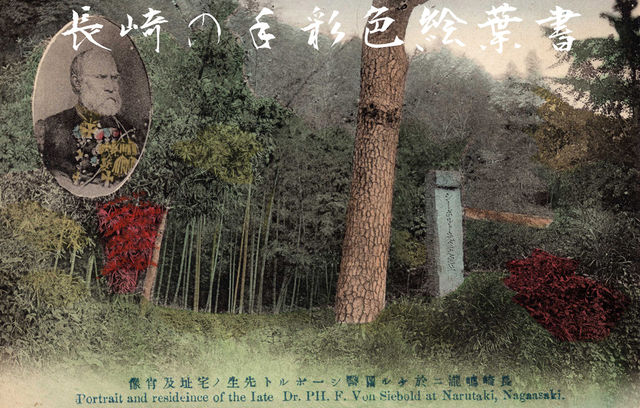

In 1824, Siebold established a private medical school known as the Narutaki-juku in Nagasaki. This institution became a vibrant intellectual hub, attracting around 50 rangaku-sha (scholars of Western learning) from various parts of Japan, including prominent figures such as Takano Chōei, Ninomiya Keisaku, Itō Genboku, Koseki San'ei, and Itō Keisuke. These students not only received instruction in Western medicine but also assisted Siebold in his botanical and naturalistic studies. Dutch became the common language for academic and scholarly exchanges for a generation, a practice that continued until the Meiji Restoration.

Siebold famously refused monetary payment for his medical services, instead accepting various objects and artifacts as tokens of gratitude from his patients. These everyday items, including household goods, woodblock prints, tools, and handcrafted objects, formed the foundation of his extensive ethnographic collection, which later gained significant historical value.

3.2. Research on Japanese Flora, Fauna, and Ethnography

Siebold's primary interest in Japan lay in the comprehensive study of its unique flora and fauna. He meticulously collected as many specimens as possible, amassing over 1,000 native plant species in a small botanical garden established behind his residence on Dejima. He even constructed a greenhouse to cultivate Japanese plants, aiming to acclimate them for transport to the Dutch climate.

He collaborated extensively with Japanese naturalists and artists. Local artists like Kawahara Keiga were employed to create detailed botanical illustrations of his plant collection, as well as depictions of daily life in Japan, which further enriched his ethnographic records. He also hired Japanese hunters to track rare animals and collect specimens. His Japanese collaborators included Keisuke Ito (1803-1901), Mizutani Sugeroku (1779-1833), Ōkochi Zonshin (1796-1882), and Katsuragawa Hoken (1797-1844), a physician to the shogun. His assistant and eventual successor, Heinrich Bürger (1806-1858), an apothecary and mineralogist, proved indispensable, and the painter Carl Hubert de Villeneuve, sent by the Dutch East Indies government in 1825, taught Kawahara Western painting techniques.

Siebold was instrumental in introducing several familiar garden plants to Europe, including the Hosta and the Hydrangea otaksa (named after his Japanese partner, Kusumoto Taki). Notably, he also managed to smuggle germinative seeds of tea plants (Camellia sinensis) to the Buitenzorg botanical garden in Batavia. This act, undertaken without the knowledge of the Japanese government which strictly controlled tea trade, initiated the tea culture on Java, then a Dutch colony. By 1833, Java boasted over half a million tea plants. However, he also introduced Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), which later became a highly invasive weed in Europe and North America, all deriving from a single female plant he collected.

During his stay, Siebold dispatched three shipments containing numerous herbarium specimens to Leiden, Ghent, Brussels, and Antwerp. The shipment to Leiden included the first specimens of the Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus) to reach Europe.

Siebold's demanding personality often led to conflicts with his Dutch superiors, who perceived him as arrogant. This tension resulted in an order for his recall to Batavia in July 1827. However, the ship sent for his return, the Cornelis Houtman, was shipwrecked by a typhoon in Nagasaki Bay in September 1828. The storm severely damaged Dejima and destroyed Siebold's botanical garden. Although the ship was repaired and eventually sailed for Batavia in January 1829 with 89 crates of Siebold's salvaged botanical collection, Siebold himself remained behind on Dejima.

3.3. Japanese Family

During his time in Japan, Siebold formed a personal relationship with Kusumoto Taki (楠本滝, also known as Sonogi, 1807-1865), as marriage between foreigners and Japanese was forbidden under the isolationist policy. Their daughter, Kusumoto Ine (楠本イネ), was born in 1827. Siebold affectionately called Taki "Otakusa," a name he later used to describe a variety of Hydrangea (Hydrangea otaksa). Kusumoto Ine, with her father's support, went on to become the first Japanese woman to receive formal Western medical training, becoming a highly respected practicing physician and serving as court physician to the Empress in 1882, a position she held until her death in 1903.

3.4. Journey to Edo and Information Gathering

In 1826, Siebold accompanied the Dutch trade post chief on the annual Edo Sampu (journey to Edo), a compulsory court visit to the shogun in Edo. This long journey provided him with a unique opportunity to intensely research Japan's natural environment. Along the way, he collected numerous plants and animals, diligently recording geographical features, vegetation, climate, and astronomical observations.

In Edo, Siebold expanded his network of Japanese scholars and officials, engaging in intellectual exchanges. He befriended figures such as Katsuragawa Hoken, a shogun's physician, and the scholars Udagawo Yoan and Shimazu Shigehide, a former lord of the Satsuma Domain. He also met Mogami Tokunai, an explorer known for his expeditions to northern Japan, including Emishi and Sakhalin, from whom Siebold obtained maps of these northern regions. Furthermore, he interacted with Takahashi Kageyasu, the court astronomer, to whom Siebold gifted a copy of the latest world map by Adam Johann von Krusenstern. In return, Kageyasu provided Siebold with a detailed map of Japan created by Inō Tadataka. This exchange of maps, though seemingly academic, would later have severe consequences due to Japan's strict national isolation policies.

3.5. Siebold Incident and Expulsion

The pivotal event leading to Siebold's expulsion from Japan, known as the "Siebold Incident," occurred following the accidental discovery of forbidden Japanese maps he had acquired during his Edo journey. A ship carrying some of his collected materials, which had previously been shipwrecked in Nagasaki Bay during a typhoon, resurfaced, and among the salvaged items were the detailed maps of Japan and Korea (authored by Inō Tadataka) that Takahashi Kageyasu had given him. Possession of such maps by foreigners was strictly prohibited by the Japanese government, who accused Siebold of high treason and being a Russian spy. Takahashi Kageyasu, implicated in the scandal for providing the maps, was imprisoned and subsequently died in jail.

Siebold was placed under house arrest and eventually expelled from Japan on October 22, 1829, after residing there for six years. Although he initially expected to return after a three-year ban, this hope was not realized immediately. Confident that his Japanese collaborators would continue his scientific endeavors, he departed on the frigate Java for Batavia, taking with him an immense collection of thousands of animals, plants, books, and maps. The ship arrived in Batavia on January 28, 1830, where over 2,000 species from his collection were housed at the Buitenzorg botanical garden. Siebold then returned to the Netherlands, departing Batavia on March 5, 1830, and arriving on July 7, 1830, concluding an eight-year period of his life spent in Japan and Batavia.

4. Return to Europe and Publication of Major Works

4.1. Settlement in Europe and Academic Pursuits

Philipp Franz von Siebold arrived in the Netherlands in 1830, a time of political turmoil that soon led to the Belgian Revolution and Belgium's independence. He swiftly salvaged his ethnographic collections from Antwerp and his herbarium specimens from Brussels, transporting them to Leiden with the assistance of Johann Baptist Fischer. His botanical collections of living plants were sent to the University of Ghent, where their expansion contributed to Ghent's horticultural renown. In gratitude, the University of Ghent presented him with specimens from his original collection in 1841.

Siebold settled in Leiden, bringing with him the majority of his collection. This "Philipp Franz von Siebold collection" became the earliest botanical collection from Japan, containing many type specimens. With approximately 12,000 specimens, from which he could describe about 2,300 species, it remains a subject of ongoing research today. The Dutch government purchased the entire collection for a substantial sum. Siebold also received a significant annual allowance from Dutch King William I starting in 1831, and was appointed "Advisor to the King for Japanese Affairs." In 1842, King William II further honored Siebold by raising him to the nobility as an esquire.

His "Siebold collection" was first opened to the public in 1831. In 1837, he founded a private museum in his home, which eventually evolved into the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden. His successor in Japan, Heinrich Bürger, continued Siebold's work, sending three more shipments of herbarium specimens from Japan. These collections formed the core of the Japanese collections at the National Herbarium of the Netherlands and the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie in Leiden. Both institutions later merged in 2010 to form the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, which now maintains the entire natural history collection brought back by Siebold.

In 1845, Siebold married Helene von Gagern (1820-1877), a German noblewoman. They had three sons and two daughters. From 1852, Siebold began corresponding with Russian diplomats, such as Baron von Budberg-Bönninghausen, the Russian ambassador to Prussia. This led to an invitation for Siebold to visit Saint Petersburg to advise the Russian government on establishing trade relations with Japan, a voyage he undertook without informing the Dutch government, despite still being in their employ. He also consulted with American Naval Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1854 before Perry's expedition to Japan, and notably advised Townsend Harris on how Christianity might be spread to Japan, suggesting that the Japanese "hated" Christianity based on his experiences.

4.2. Major Publications

During his residence in Leiden, Siebold embarked on the monumental task of publishing his findings and observations from Japan.

His most comprehensive work, Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan und dessen Neben- und Schutzländern: Jezo mit den Südlichen Kurilen, Krafto, Koorai und den Liukiu-Inseln (Archive for the Description of Japan and its Dependencies and Protectorates: Yezo with the Southern Kuriles, Karafuto, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands), was published in seven volumes between 1832 and 1882, with the final parts appearing posthumously. This richly illustrated ethnographical and geographical work provided unprecedented detail about Japan and its surrounding regions, including a report of his journey to the Shogunate Court at Edo. A French abridged version, Voyage au Japon Executé Pendant les Années 1823 a 1830, was also published, containing 72 plates from Nippon. In this work, Siebold famously transcribed the Mamiya Strait as "Mamiya-no-seto," making its name known globally.

The Bibliotheca Japonica, published between 1833 and 1841, was co-authored by Siebold with Joseph Hoffmann (a professor of Chinese and Japanese languages) and Kuo Cheng-Chang, a Javanese man of Chinese descent who accompanied Siebold from Batavia. This work offered a comprehensive survey of Japanese literature and included a Chinese, Japanese, and Korean dictionary. Siebold's writings on Japanese religion and customs significantly influenced early modern European understanding of Buddhism and Shinto, particularly his suggestion that Japanese Buddhism was a form of Monotheism.

The zoological descriptions of Siebold's Japanese animal collection were undertaken by renowned zoologists Coenraad Jacob Temminck (1777-1858), Hermann Schlegel (1804-1884), and Wilhem de Haan (1801-1855). Their collaborative efforts resulted in the monumental Fauna Japonica, a series of monographs published between 1833 and 1850. Primarily based on Siebold's collections (with some contributions from Heinrich Bürger), this work remarkably made the Japanese fauna the best-described non-European fauna at the time. Prominent Japanese species like the Japanese sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus), red sea bream (Pagrus major), and Japanese spiny lobster (Panulirus japonicus) received their first scientific classifications in this publication.

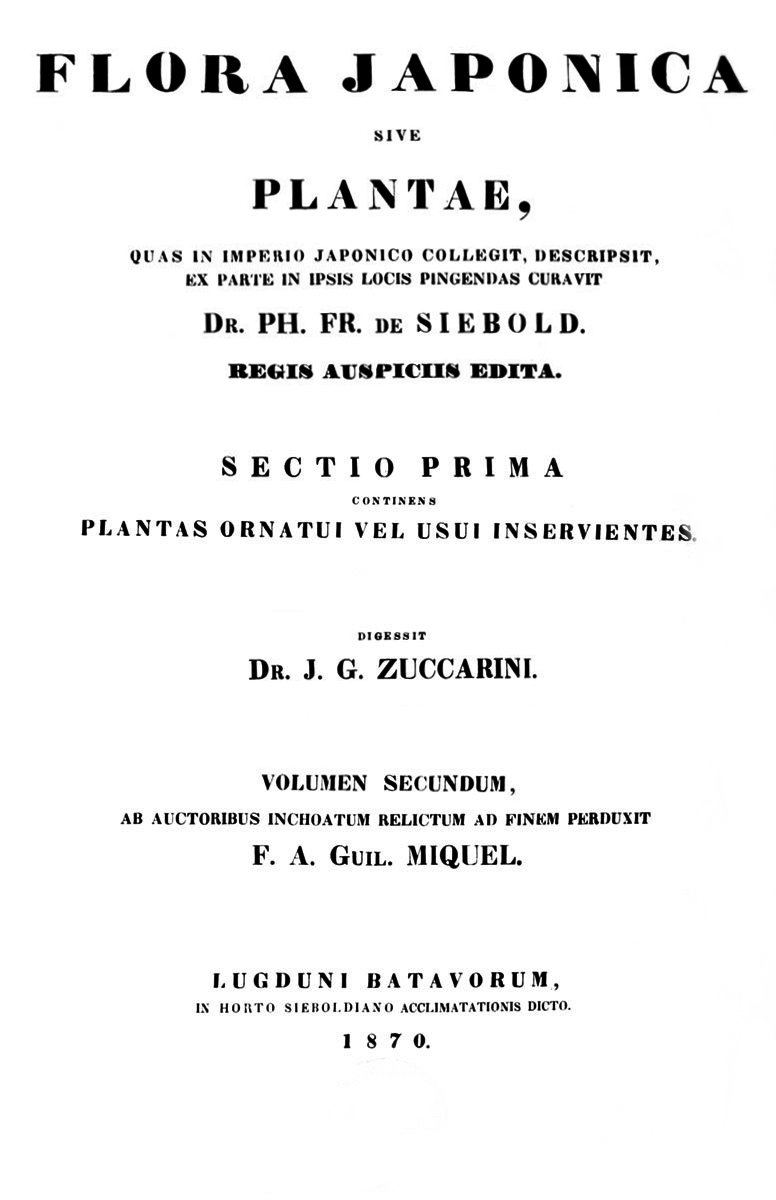

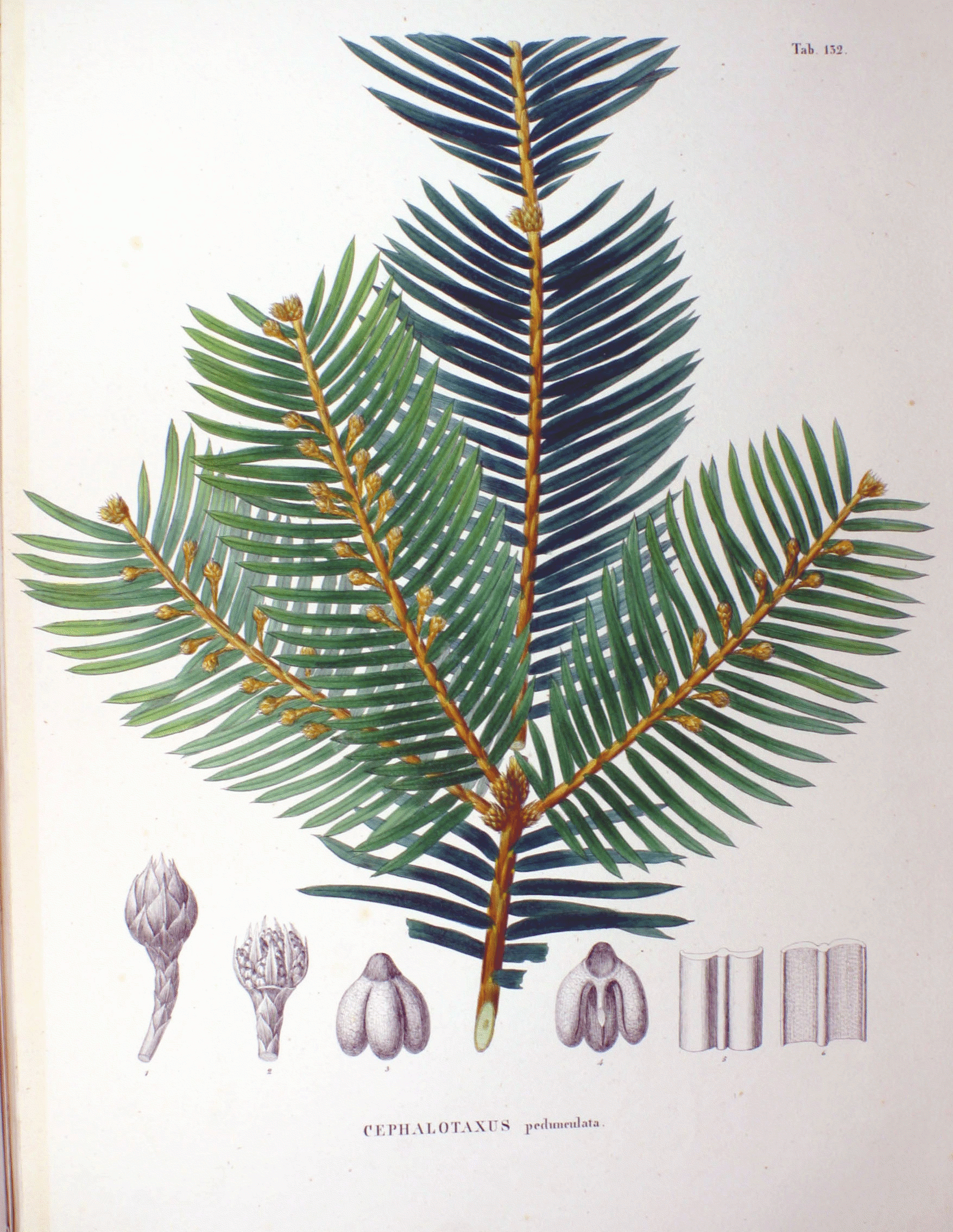

Siebold collaborated with German botanist Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini (1797-1848) on his botanical masterpiece, Flora Japonica. The first parts appeared in 1835, but the work was not fully completed until 1870, after Siebold's death, by F.A.W. Miquel (1811-1871), the director of the Rijksherbarium in Leiden. This publication solidified Siebold's scientific reputation throughout Europe.

Many of the plants Siebold introduced from Japan and cultivated at the Hortus Botanicus Leiden (Leiden Botanical Garden) subsequently spread across Europe and to other parts of the world. Familiar garden plants such as Hosta, Hortensia, Azalea, Japanese butterbur, coltsfoot, and Japanese larch became common in gardens worldwide.

The standard author abbreviation Siebold is used to indicate Philipp Franz von Siebold as the authority when citing a botanical name.

5. Second Visit to Japan and Later Life

5.1. Return to Japan as an Advisor

In 1858, the Japanese government officially lifted the banishment order against Siebold, following the country's opening through the Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1854 and the Dutch-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1858. Siebold returned to Japan on August 4, 1859, serving as an advisor to Albert Bauduin, the agent of the Dutch Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij) in Nagasaki. His eldest son, Alexander, then 12 years old, accompanied him on this journey. However, after two years, the connection with the Trading Society was severed as Siebold's advice was deemed of little practical value. During this period in Nagasaki, he fathered another child with one of his female servants.

In 1861, Siebold secured an appointment as an advisor to the Japanese government and relocated to Edo. He attempted to position himself as an intermediary between foreign representatives and the Japanese authorities. However, this involvement in politics directly contradicted strict admonitions from Dutch authorities prior to his return to Japan. Consequently, the Dutch Consul General in Japan, J.K. de Wit, was ordered to request Siebold's removal from his advisory position.

5.2. Second Period of Activity in Japan and Return to Europe

During his second stay, Siebold continued his extensive collection efforts and natural observations. He also actively provided information on the Japanese situation to various foreign entities, including the Prussian expedition, the Russian Navy, the French minister, and the Dutch colonial minister. His son, Alexander, even presented a Japanese map to the commander of the Russian Far East Expeditionary Corps, Likhachov.

Despite his renewed efforts, Siebold's political meddling and financial issues caused friction. He was ordered to return to Batavia and then to Europe, departing Nagasaki with a vast collection of newly acquired materials in May 1862. He arrived back in Bonn, Germany, on January 10, 1863. Upon his return, he requested the Dutch government appoint him as Consul General in Japan, but this request was denied due to the significant debt he had accumulated from loans. He was, however, granted an honorary promotion to Major General in the Dutch East Indies Army in 1863, and his pension continued to be paid, though all other relations with the Dutch government were severed. He attempted to sell his second collection of about 2,500 items to the Dutch government, but the offer was rejected due to its high price.

In 1864, Siebold resigned from his Dutch official position and returned to his hometown of Würzburg. He also collaborated with Ikeda Nagaoki, the chief envoy of the Japanese mission to Europe in Paris, but was notably reluctant to return 20-30 boxes of mineral specimens that had been lent to him by Miyake Gonsai, the father of Miyake Hoshu. Only three boxes were eventually returned years later.

5.3. Later Life and Death

Siebold spent his final years in Europe, continuing his academic pursuits despite facing financial difficulties and a deteriorating relationship with the Dutch government. He organized exhibitions of his Japanese collections, opening a "Japan Museum" in a high school in Würzburg in 1864 and another in Munich in 1866. He persistently sought funding for another expedition to Japan, first from the Russian government, which proved unsuccessful, and then from the French government in Paris in 1865, where he also failed to secure support.

Philipp Franz von Siebold died in Munich on October 18, 1866, at the age of 70, due to complications from a cold and sepsis. His grave, shaped like a Buddhist pagoda, is located in the Old Southern Cemetery of Munich (Alter Münchner SüdfriedhofAl-ter Myun-kner Zyuet-freed-hofGerman). He is further commemorated in Munich through a street named after him and numerous mentions in the city's Botanical Garden.

6. Legacy and Impact

6.1. Academic Legacy

Siebold's influence spanned multiple academic fields, including botany, zoology, and Japanese studies. His meticulous collections and comprehensive publications made significant contributions to scholarly research. His extensive botanical collection, particularly the earliest specimens from Japan, with around 12,000 items from which 2,300 species were described, continues to be a subject of ongoing study. These collections are preserved in various European institutions, including Leiden, Munich, and Vienna. The Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden currently houses his zoological and botanical specimens from his first stay in Japan (1823-1829), comprising 200 mammals, 900 birds, 750 fish, 170 reptiles, over 5,000 invertebrates, 2,000 different plant species, and 12,000 herbarium specimens. The Royal Scientific Academy of Saint Petersburg even purchased 600 colored plates from his Flora Japonica.

His collections were instrumental in founding the ethnographic museums in Munich and Leiden. His son, Alexander von Siebold, later donated much of the material left behind after Siebold's death in Würzburg to the British Museum in London. Another son, Heinrich von Siebold (1852-1908), often called "Little Siebold," continued his father's research, notably in archaeology. He is recognized, alongside Edward S. Morse, as one of the founders of modern archaeological efforts in Japan, having coined the term "archaeology" (考古学, kōkogaku) in Japanese through his work Kōko Setsuryaku.

6.2. Cultural Influence and Assessment

Siebold played a crucial role in fostering cultural exchange and mutual understanding between Japan and the West. His efforts significantly contributed to the dissemination of Western medicine in Japan and provided unparalleled insights into Japanese society, culture, and natural history for European audiences.

Although he is widely recognized and revered in Japan, where he is affectionately known as "Shiboruto-san" and mentioned in school textbooks, he remains less known elsewhere, except among gardeners who recognize the many plants named after him. To commemorate his legacy, the Hortus Botanicus Leiden has established the "Von Siebold Memorial Garden," a Japanese garden featuring plants sent by Siebold himself. This garden, situated under a 150-year-old Zelkova serrata tree that dates back to Siebold's lifetime, attracts numerous Japanese visitors who come to pay their respects.

6.3. Memorial Facilities and Collection Preservation

Several institutions and sites are dedicated to preserving Siebold's work and commemorating his achievements:

- The SieboldHuis in Leiden, Netherlands, is a museum located in Siebold's transformed former home, showcasing highlights from his Leiden collections and Dutch-Japanese history.

- The Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands, houses the vast zoological and botanical specimens Siebold collected during his first stay in Japan (1823-1829).

- The National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, Netherlands, preserves the large ethnographic collection assembled by Siebold during his first Japanese sojourn.

- The State Museum of Ethnology in Munich, Germany, houses Siebold's collections from his second voyage to Japan (1859-1862). It is notable that Siebold himself urged King Ludwig I of Bavaria to establish an ethnology museum in Munich.

- A Siebold-Museum exists in Würzburg, Germany, his birthplace.

- Another Siebold-Museum is located on Brandenstein Castle in Schlüchtern, Germany.

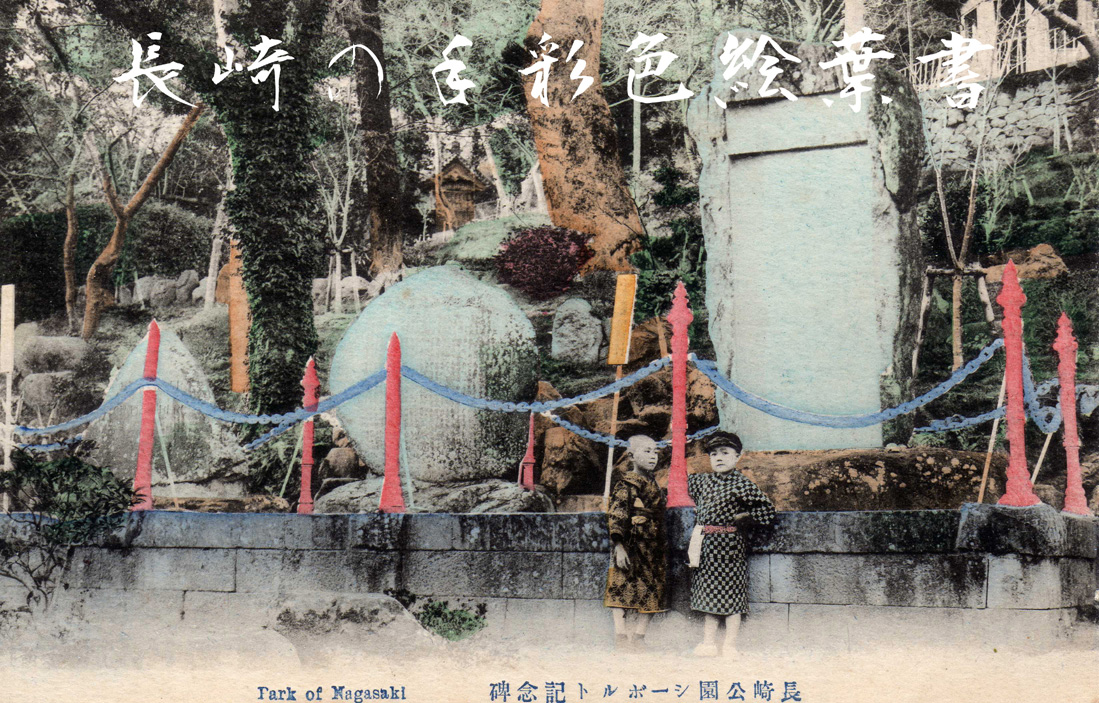

- In Japan, the Siebold Memorial Museum in Nagasaki pays tribute to him, located on property adjacent to his former residence in the Narutaki neighborhood. It is the first museum in Japan dedicated to a non-Japanese individual.

6.4. Family and Descendants

Philipp Franz von Siebold had children with both his Japanese partner and his European wife, and his descendants continue to uphold his legacy.

With Kusumoto Taki, he had his eldest daughter, Kusumoto Ine (1827-1903). Ine went on to become the first Japanese woman to receive Western medical training and a highly regarded physician, serving as a court physician to the Empress. Her daughter, Kusumoto Takako (also known as Yamawaki Taka, 1852-1938), was Siebold's granddaughter. She initially pursued medicine but later married a doctor and published her memoirs.

With his European wife, Helene von Gagern, Siebold had three sons and two daughters:

- Alexander von Siebold (August 16, 1846 - January 23, 1911) was his eldest son with Helene. He accompanied his father on the second visit to Japan in 1859, at the age of 12. Alexander remained in Japan, serving as an interpreter for the British Legation and later as a special secretary to Japanese Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru, maintaining close ties with prominent Meiji-era figures like Mutsu Munemitsu. He authored Siebold Saigo no Nihon Ryoko (Siebold's Last Journey to Japan). He also played a role in assisting the Meiji government with matters such as preventing counterfeit currency.

- Heinrich von Siebold (also known as Henry von Siebold or "Little Siebold") (July 21, 1852 - August 11, 1908) was his second son with Helene. He traveled to Japan in 1869 with his elder brother. While serving as an interpreter and diplomat for the Austro-Hungarian embassy, he undertook significant archaeological research. His work Kōko Setsuryaku (Brief Account of Archaeology) introduced the term "archaeology" to Japan, earning him recognition alongside Edward S. Morse as a co-founder of modern Japanese archaeology. He married Iwamoto Hana in Japan and had a son and a daughter.

- Helene (1848-1927) was his second daughter, who married Baron Maximilian von Ulm zu Erbach.

- Mathilde (1850-1906) was his third daughter, who married Gustav von Brandenstein. Their son Alexander married Helene, the only daughter of Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the famous airship pioneer. Their descendants carry the family name von Brandenstein-Zeppelin. The German Siebold Society, based in Würzburg, is chaired by a descendant of this line.

- Maximilian von Siebold (1854-1887) was his third son, who served as a non-commissioned officer in the Dutch East Indies.

Today, Siebold's direct descendants include the Kusumoto family (through Kusumoto Ine), the Horiuchi family, the Sekiguchi family (through Heinrich), the Inoue family, and the Brandenstein-Zeppelin family in Germany (through Mathilde). Notably, representatives from these branches, including Sekiguchi Tadasuke (Heinrich's descendant), Konstantin Brandenstein-Zeppelin (Mathilde's descendant and chairman of the German Siebold Society), and Kusumoto Sadao (Ine's descendant), were invited to the commemorative ceremony in Nagasaki in 2023, marking 200 years since Siebold's arrival in Japan.

7. Siebold in Popular Culture

Philipp Franz von Siebold has been a subject of various popular culture works, reflecting his enduring presence in the collective memory, particularly in Japan.

- Novels:

- French author Alphonse Daudet featured Siebold in his short story "L'Empereur aveugle" (The Blind Emperor), part of his collection Contes du lundi (Monday Tales). The story explores Daudet's interactions with an aging Siebold.

- Japanese author Yoshimura Akira wrote Fon Siebold no Musume (Siebold's Daughter), a fictionalized account that incorporates elements of Siebold's life and the life of his daughter, Kusumoto Ine. Yoshimura also explored themes related to Siebold's era in Chōei Tōbō (Chōei's Escape).

- Manga:

- He appears in Minamoto Taro's historical manga Fūunji-tachi (Men of the Storm).

- He is featured in Mafune Kazuo's medical manga Super Doctor K.

- Siebold makes an appearance in the gag manga series Masuda Kōsuke Gekijō Gag Manga Biyori, specifically in Chapter 197 of Volume 11.

- The character is also found in Ame Arare's Kagerō Inazuma Mizu no Tsuki within the collection Nagasaki Bōjō.

- Television Dramas:

- Siebold was portrayed by actor Eric Boschick in the 2010 NHK Saturday jidaigeki (period drama) Katsura Chizuru Shinsatsu Niroku.

- Stage Productions:

- A stage play titled "Siebold Oyako-den ~ Aoi Me no Samurai ~" (The Story of Siebold and His Son ~ The Blue-Eyed Samurai ~) has been performed in 2020, 2021, and 2022 at the Tsukiji Honganji Buddhist Hall.

8. Names Commemorating Siebold

Philipp Franz von Siebold's legacy is honored through numerous plants, animals, places, institutions, and services named after him, particularly using the Latinized forms "sieboldii" or "sieboldiana."

- Plants:

- Acer sieboldianum (Siebold's Maple): A species of maple native to Japan.

- Asiasarum sieboldii (Usubasaisin)

- Berberis sieboldii (Hebinoborazu)

- Calanthe sieboldii (Siebold's Calanthe): A terrestrial evergreen orchid found in Japan, Ryukyu Islands, and Taiwan.

- Castanopsis sieboldii (Sudajii)

- Cirsium sieboldii (Kiseruazami)

- Clematis florida var. sieboldiana (syn: C. florida 'Sieboldii' & C. florida 'Bicolor'): A distinctive and sought-after variety of clematis.

- ツノハシバミCorylus sieboldianaJapanese: The Asian beaked hazel, found in northeastern Asia and Japan.

- Dryopteris sieboldii: A fern characterized by leathery fronds.

- Hosta sieboldii: A popular garden plant with many distinct cultivars.

- Hylotelephium sieboldii (Misebaya)

- Magnolia sieboldii: The "Oyama" magnolia, a small tree or large shrub.

- Malus sieboldii (Toringo Crab-Apple): Originally named Sorbus toringo by Siebold, known for its fragrant pink buds fading to white.

- Populus tremula var. sieboldii (Yamanarashi)

- Primula sieboldii (Sakurasou): The Japanese woodland primula.

- Prunus sieboldii: A flowering cherry species.

- Sedum sieboldii: A succulent whose leaves form rose-like whorls.

- Stachys sieboldii (Chorogi)

- Tsuga sieboldii: A Japanese hemlock.

- Viburnum sieboldii (Gomagi): A deciduous large shrub with creamy white flowers and red berries.

Flowering Malus sieboldii (Toringo Crab-Apple). Magnolia sieboldii.

Primula sieboldii. - Animals:

- Anotogaster sieboldii (Onyanma): The largest dragonfly in Japan.

- Conus sieboldii (Reeve, 1848) (Akomegai): A species of cone snail.

- Enhydris sieboldii (Siebold's smooth water snake).

- Nordotis gigantea: Commonly known as Siebold's abalone, prized for sushi.

- Nipponocypris sieboldii (Temminck et Schlegel, 1846) (Numamutsu): A freshwater fish of the Cyprinidae family.

- Pharaonella sieboldii (Deshayes, 1855) (Benigai): A bivalve mollusk related to the Sakuragai.

- Pheretima sieboldi (Horst, 1883) (Sieboldmimuzu): A large earthworm.

- Pristipomoides sieboldii (Bleeker, 1857) (Himedai): A marine fish of the Lutjanidae family.

- Sieboldius: A genus of large gomphid dragonflies.

- Treron sieboldii (Temminck, 1835) (Aobato): A species of forest pigeon.

- Zacco sieboldii: A species of fish.

- Places, Institutions, and Services:

- University of Nagasaki Siebold Campus: Formerly Prefectural Nagasaki Siebold University.

- "Siebold": A former special express train operated by JR Kyushu between Sasebo Station and Nagasaki Station.

- Siebold-dori: A street in Nagasaki City connecting the Siebold residence ruins to the Shindaikumachi shopping district.

- Siebold no Yu: A public bath in Ureshino City, Saga Prefecture.

- SieboldHuis: A museum in Leiden, Netherlands, housed in Siebold's former residence.

- Siebold Memorial Museum: Located in Nagasaki, Japan, near Siebold's former residence in Narutaki.

- Siebold Typhoon: A common name for the typhoon that struck Nagasaki in 1828.

- Juhachi Bank Siebold Branch: A virtual branch used for payment reconciliation services.

- Philipp Franz von Siebold Award: An award commemorating his contributions.

Japanese stamp commemorating Siebold's 200th birthday.

Siebold-dori (Siebold Street) in Nagasaki City. Young Siebold statue by Tominaga Naoki (1979) at Siebold Memorial Museum. - A Japanese stamp was issued to commemorate Siebold's 200th birthday.

- The "Young Siebold" statue by Tominaga Naoki (1979) is displayed at the Siebold Memorial Museum in Nagasaki.