1. Overview

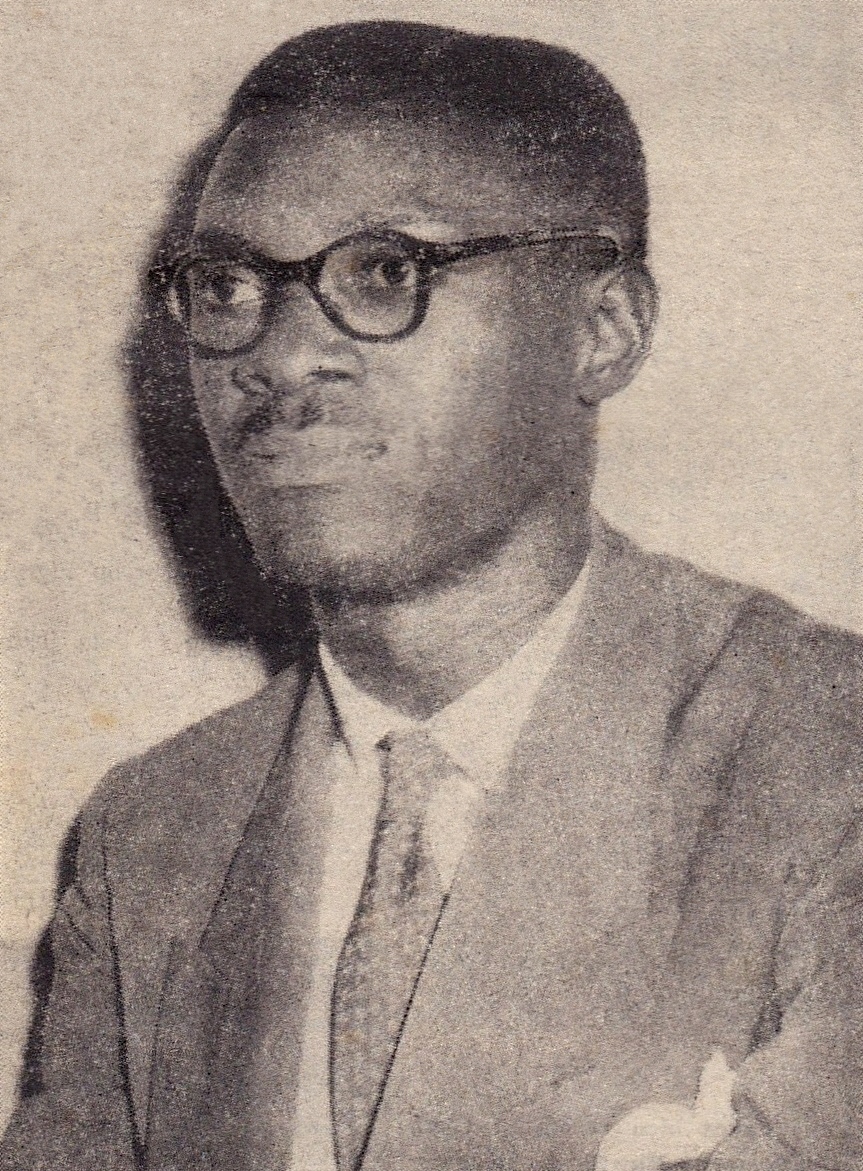

Patrice Émery Lumumba was a pivotal Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from June to September 1960. His leadership was instrumental in transforming the Belgian Congo from a colonial territory into an independent republic, driven by strong African nationalism and pan-Africanist ideals. Lumumba's brief but impactful tenure was marked by the tumultuous Congo Crisis, which saw army mutinies, secessionist movements, and significant foreign intervention. His appeals for international support, particularly from the United Nations and later the Soviet Union, were met with suspicion by Western powers, who feared his perceived communist leanings during the Cold War. This geopolitical struggle, coupled with internal power dynamics and the machinations of external actors, ultimately led to his downfall. Lumumba was overthrown in a coup, arrested, and brutally assassinated in January 1961 by separatist Katangan authorities with the direct involvement of Belgian mercenaries and the complicity of Belgian, United States, and United Kingdom intelligence services. His tragic death, a direct consequence of foreign intervention and the struggle for self-determination, cemented his status as a martyr for anti-colonial and pan-African movements worldwide, highlighting the profound social and political impacts of external interference on newly independent nations.

2. Early life and background

Patrice Lumumba's early life was shaped by his origins in rural Belgian Congo and his exposure to both traditional African and European educational systems, which fostered an early intellectual curiosity and a critical perspective on colonial rule.

2.1. Early childhood and education

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925 as Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa in Onalua, a village in the Katakokombe region of the Kasai Province in the Belgian Congo. His parents were Julienne Wamato Lomendja and François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer. Both were members of the Tetela people and raised in a Catholic family. His original surname, Okit'Asombo, is derived from the Tetela language words okitáttl/okitɔttl ('heir', 'successor') and asombóttl ('cursed or bewitched people who will die quickly'). Lumumba had three brothers, Charles Lokolonga, Émile Kalema, and Louis Onema Pene Lumumba, and one half-brother, Jean Tolenga.

He received his early education at a Protestant primary school, followed by a Catholic missionary school, and finally a government post office training school, where he completed a one-year course with distinction. Despite the limited resources in missionary schools, such as a lack of electricity and basic textbooks, Lumumba proved to be a bright student. His teachers recognized his quick intellect, lending him their own books to encourage his learning, though some found his frequent and challenging questions troublesome. Lumumba was known for being a vocal and precocious young man, often pointing out his teachers' errors in front of his peers, an outspoken nature that would characterize his later life. He was multilingual, speaking Tetela, French, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba. Beyond his formal studies, Lumumba developed an interest in Enlightenment ideals, reading works by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire. He also admired the literary works of Molière and Victor Hugo, and wrote poetry with strong anti-imperialist themes.

2.2. Early career

After completing his education, Lumumba left his hometown and began his professional life. He worked as a traveling beer salesman in Léopoldville before securing a position as a postal clerk in Stanleyville, where he worked for eleven years. In Stanleyville, he quickly emerged as a community leader, organizing a trade union for postal workers. His activism was encouraged by local members of the Belgian Liberal Party.

In 1952, Lumumba was employed as a personal assistant to French sociologist Pierre Clément, who was conducting a study in Stanleyville. That same year, he co-founded and became president of the Stanleyville chapter of the Association des Anciens élèves des pères de Scheut (ADAPÉS), an alumni association for former students of Scheut schools, despite never having attended one himself. By 1955, Lumumba had become the regional head of the Cercles of Stanleyville and formally joined the Liberal Party of Belgium, actively editing and distributing party literature. Between 1956 and 1957, he wrote his autobiography, which was posthumously published in 1962. Following a study tour in Belgium in 1956, he was arrested and charged with embezzling 2.50 K USD from the post office. He was convicted and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment and a fine a year later. Lumumba was married three times: Henriette Maletaua (divorced 1947), Hortense Sombosia (divorced 1947), and Pauline Opangu (married 1951). His relationship with Pauline Kie resulted in a son, François Lumumba, and he remained close with Kie until his death, though he married Pauline Opangu in 1951.

3. Political career

Patrice Lumumba's political career was characterized by his rapid ascent as a nationalist leader who championed a unified, independent Congo, challenging colonial structures and advocating for self-determination.

3.1. Leader of the Congolese National Movement (MNC)

After his release from prison, Lumumba played a crucial role in co-founding the Congolese National Movement (MNC) party on 10 October 1958, quickly rising to become its leader. Unlike many other Congolese political parties of the era, the MNC deliberately avoided aligning with a specific ethnic group or region, instead promoting a broad platform centered on immediate independence, the gradual Africanisation of government institutions, state-led economic development, and a policy of neutrality in foreign affairs. Lumumba's charismatic personality and exceptional public speaking skills quickly earned him prominence within the party and a large popular following across the Congo. This widespread support provided him with greater political autonomy compared to other contemporary leaders who were often more reliant on Belgian connections.

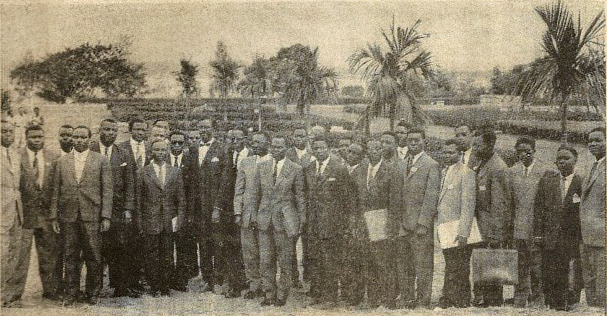

In December 1958, Lumumba represented the MNC at the All-African Peoples' Conference held in Accra, Ghana. This international gathering, hosted by Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah, allowed Lumumba to further solidify his pan-Africanist credentials. Nkrumah was reportedly impressed by Lumumba's intelligence and capabilities. In 1959, the MNC experienced a split, leading to the formation of the majority MNC-L, led by Lumumba, and the more radical and federalist MNC-K. In late October 1959, Lumumba was arrested for inciting an anti-colonial riot in Stanleyville that resulted in 30 deaths and was sentenced to six months in prison. His trial was scheduled to begin on 18 January 1960, coinciding with the first day of the Congolese Round Table Conference in Brussels, which aimed to plan the future of the Congo. Despite his imprisonment, the MNC secured a convincing majority in the December local elections in the Congo. Due to significant pressure from delegates who were upset by his trial, Lumumba was released and permitted to attend the Brussels conference, where his dramatic presence garnered considerable attention from other Congolese leaders.

3.2. Independence and premiership

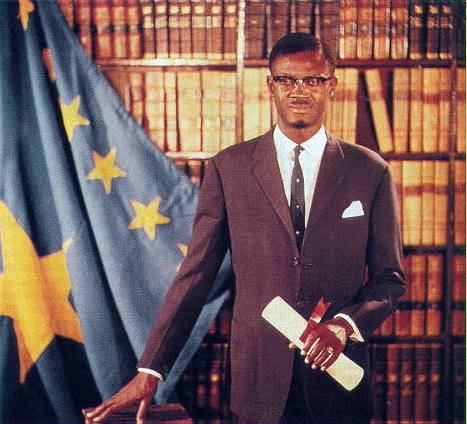

The Brussels conference concluded on 27 January 1960 with a declaration of Congolese independence, setting 30 June 1960 as the independence date and scheduling national elections from 11 to 25 May 1960. The MNC, under Lumumba's leadership, won a plurality of seats in the election, securing 40 out of 137 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and gaining significant positions in four of the six provinces. Six weeks before independence, Walter Ganshof van der Meersch was appointed as the Belgian Minister of African Affairs, effectively becoming Belgium's de facto resident minister in the Congo, administering it jointly with Governor-General Hendrik Cornelis. Ganshof was tasked with advising King Baudouin on the selection of a formateurFrench (a person charged with forming a government).

On 8 June 1960, Ganshof flew to Brussels to consult with King Baudouin, suggesting Lumumba, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, or a third individual as formateurFrench. Upon his return to the Congo on 12 June, Ganshof appointed Lumumba as the informateurFrench, tasked with exploring the possibility of forming a national unity government by 16 June. Simultaneously, the parliamentary opposition coalition, the Cartel d'Union NationaleFrench, was announced. Lumumba initially struggled to connect with members of this cartel, whose positions remained entrenched. Despite Ganshof's attempts to mediate, Lumumba's mission appeared unlikely to succeed, leading Ganshof to terminate his mission on 17 June and advise King Baudouin to name Kasa-Vubu as formateurFrench. Lumumba, however, threatened to form his own government without official approval, announcing the creation of a "popular" government with the support of Pierre Mulele of the PSA.

Kasa-Vubu, like Lumumba, faced difficulties in forming a government without broad support. Most party leaders refused to back a government that excluded Lumumba. The decision to appoint Kasa-Vubu as formateurFrench ironically rallied the PSA, CEREA (Centre de Regroupement AfricainFrench), and BALUBAKAT (Association Générale des Baluba du KatangaFrench) to Lumumba's side, making it improbable for Kasa-Vubu to win a vote of confidence. On 21 June, the Chamber of Deputies elected Joseph Kasongo of the MNC-L as its president with a majority of 74 votes, with vice presidencies secured by PSA and CEREA candidates, both supported by Lumumba. Recognizing Lumumba's parliamentary control, King Baudouin, on Ganshof's renewed advice, appointed Lumumba as formateurFrench.

With Lumumba's bloc controlling parliament, several opposition members sought to negotiate for a coalition government. By 22 June, Lumumba had a government list, but negotiations continued with Jean Bolikango, Albert Delvaux, and Kasa-Vubu. Kasa-Vubu demanded significant ministerial positions and a pledge of support for his presidential candidacy, which Lumumba could not guarantee. Lumumba also offered Albert Kalonji the agriculture portfolio, which he rejected, and Cyrille Adoula a ministerial position, which he refused. On 23 June, Lumumba presented his proposed government to the press, notably excluding the ABAKO and MNC-Kalonji (MNC-K). This exclusion angered the Bakongo of Léopoldville, who called for a general strike. Negotiations resumed, and Kasa-Vubu eventually agreed to Lumumba's earlier offer, though without a presidential candidacy guarantee.

The resulting 37-member Lumumba Government was remarkably diverse, encompassing members from various classes, tribes, and political affiliations. Despite questionable loyalties from some members, most did not openly contradict Lumumba due to political considerations or fear. On 23 June, the Chamber of Deputies convened to vote on Lumumba's government. Lumumba delivered a speech promising national unity, adherence to the people's will, and a neutralist foreign policy, which was well-received. However, reaching a majority was challenging as some parties had not been consulted, and individuals were upset about their exclusion. Deputies expressed dissatisfaction over provincial and party representation, with Kalonji threatening secession for Kasaï. The vote saw 74 in favor, five against, and one abstention out of 80 present members, with 57 voluntary absences. This was a disappointment for the MNC-L coalition.

The Senate convened on 24 June, where Iléo and Adoula voiced strong dissatisfaction. Members of the CONAKAT abstained. A decisive vote of approval was taken: 60 in favor, 12 against, and eight abstentions. This officially invested the Lumumba government, effectively reducing the parliamentary opposition to only the MNC-K and a few individuals.

At the outset of his premiership, Lumumba pursued two primary objectives: to ensure that independence translated into tangible improvements in the quality of life for the Congolese people and to unify the country as a centralized state by eradicating tribalism and regionalism. He anticipated swift opposition and recognized the need for decisive action. To achieve the first goal, Lumumba believed in a comprehensive "Africanization" of the administration, despite potential inefficiencies. The Belgians, however, resisted this, fearing an influx of unemployed civil servants into Belgium. Lumumba also proposed reducing sentences for all prisoners and granting amnesty for those serving three years or less, but this was thwarted by Belgian officials who feared it would jeopardize law and order, further souring Lumumba's view of the Belgians and deepening his concern that independence might not feel "real" to the average Congolese citizen.

In his pursuit of national unity, Lumumba was profoundly influenced by Kwame Nkrumah and Ghana's vision for leadership in post-colonial Africa. He aimed to merge the MNC with its parliamentary allies-CEREA, the PSA, and possibly BALUBAKAT-to form a single national party, fostering a following in each province. He hoped this unified party would absorb other political groups and become a cohesive force for the country.

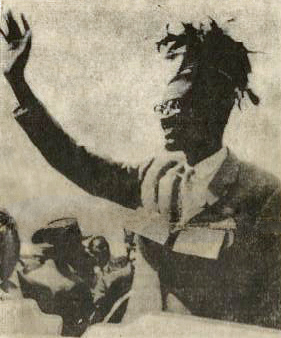

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June 1960 with a ceremony attended by numerous dignitaries, including King Baudouin of Belgium, and extensive foreign press coverage. King Baudouin's speech praised colonial developments and referenced the "genius" of his great-granduncle Leopold II of Belgium, notably omitting the atrocities committed during his reign. He advised against "hasty reforms" and encouraged continued reliance on Belgium. Lumumba, who was not scheduled to speak, delivered an impromptu address that sharply contrasted with the King's remarks. He reminded the audience that Congo's independence was not a gift but had been "won by fighting, a day-to-day fight, an ardent and idealistic fight, a fight in which we were spared neither privation nor suffering, and for which we gave our strength and our blood." He expressed pride in this "noble and just struggle," which was "indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force." This powerful speech shocked most European journalists and drew criticism from the Western media, with Time magazine characterizing it as a "vicious attack."

4. Congo Crisis and downfall

Lumumba's premiership was immediately plunged into the Congo Crisis, a period marked by internal strife, secessionist movements, and escalating foreign intervention that ultimately led to his tragic downfall.

4.1. Army mutiny and secession

The day after independence, on 1 July, Lumumba declared a general amnesty for prisoners, though it was never implemented. On 3 July, Lumumba convened the Council of Ministers to address growing unrest within the Force Publique, the Congolese army. Many soldiers, expecting immediate promotions and material benefits after independence, were disappointed by the slow pace of reform and felt that the new Congolese political class was enriching itself at their expense. On the morning of 5 July 1960, General Émile Janssens, the Force Publique commander, attempted to enforce discipline by writing "before independence = after independence" on a blackboard for emphasis. That evening, Congolese soldiers sacked the canteen in protest, leading to a mutiny that quickly spread from Camp Léopold II to Camp Hardy in Thysville.

The following day, Lumumba dismissed Janssens and promoted all Congolese soldiers by one grade, but the mutinies continued to spread throughout the Lower Congo. Despite government efforts, including Lumumba's radio address promising "thoroughgoing reforms," the unrest persisted. Mutineers in Léopoldville and Thysville only surrendered after the personal intervention of Lumumba and President Kasa-Vubu. On 8 July, Lumumba renamed the Force Publique the Armée Nationale CongolaiseFrench (ANC) and Africanized its leadership, appointing Sergeant Major Victor Lundula as general and commander-in-chief, and former soldier Joseph Mobutu as colonel and Army chief of staff. These promotions were made despite Lundula's inexperience and rumors of Mobutu's ties to Belgian and US intelligence. By 9 July, mutinies had engulfed the entire country, leading to violence against Europeans, including the murder of approximately two dozen. Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu embarked on a national tour to promote peace and appoint new army commanders.

Belgium intervened on 10 July, deploying 6,000 troops to the Congo, ostensibly to protect its citizens. Many Europeans fled to Katanga Province, which held much of the Congo's natural resources. Lumumba, though angered, initially condoned the intervention on 11 July, provided Belgian forces only protected their citizens, followed Congolese military direction, and ceased operations once order was restored. However, the same day, the Belgian Navy bombarded Matadi, killing 19 Congolese civilians and escalating tensions, leading to renewed attacks on Europeans. Belgian forces subsequently occupied cities across the country, including the capital, clashing with Congolese soldiers, which generally worsened the situation for the Congolese armed forces.

On 11 July, the State of Katanga declared independence under regional premier Moïse Tshombe, with significant support from the Belgian government and mining companies like Union Minière du Haut Katanga. Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu, denied access to Élisabethville's airstrip, returned to the capital and protested the Belgian deployment to the United Nations, requesting their withdrawal and replacement by an international peacekeeping force. The UN Security Council passed United Nations Security Council Resolution 143, calling for the immediate removal of Belgian forces and the establishment of the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC). Despite the arrival of UN troops, unrest continued. Lumumba requested UN troops to suppress the rebellion in Katanga, but their mandate did not authorize such action. On 14 July, Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu severed diplomatic relations with Belgium. Frustrated by the West's perceived inaction, they telegraphed Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, requesting close monitoring of the situation.

4.2. Foreign intervention and power struggle

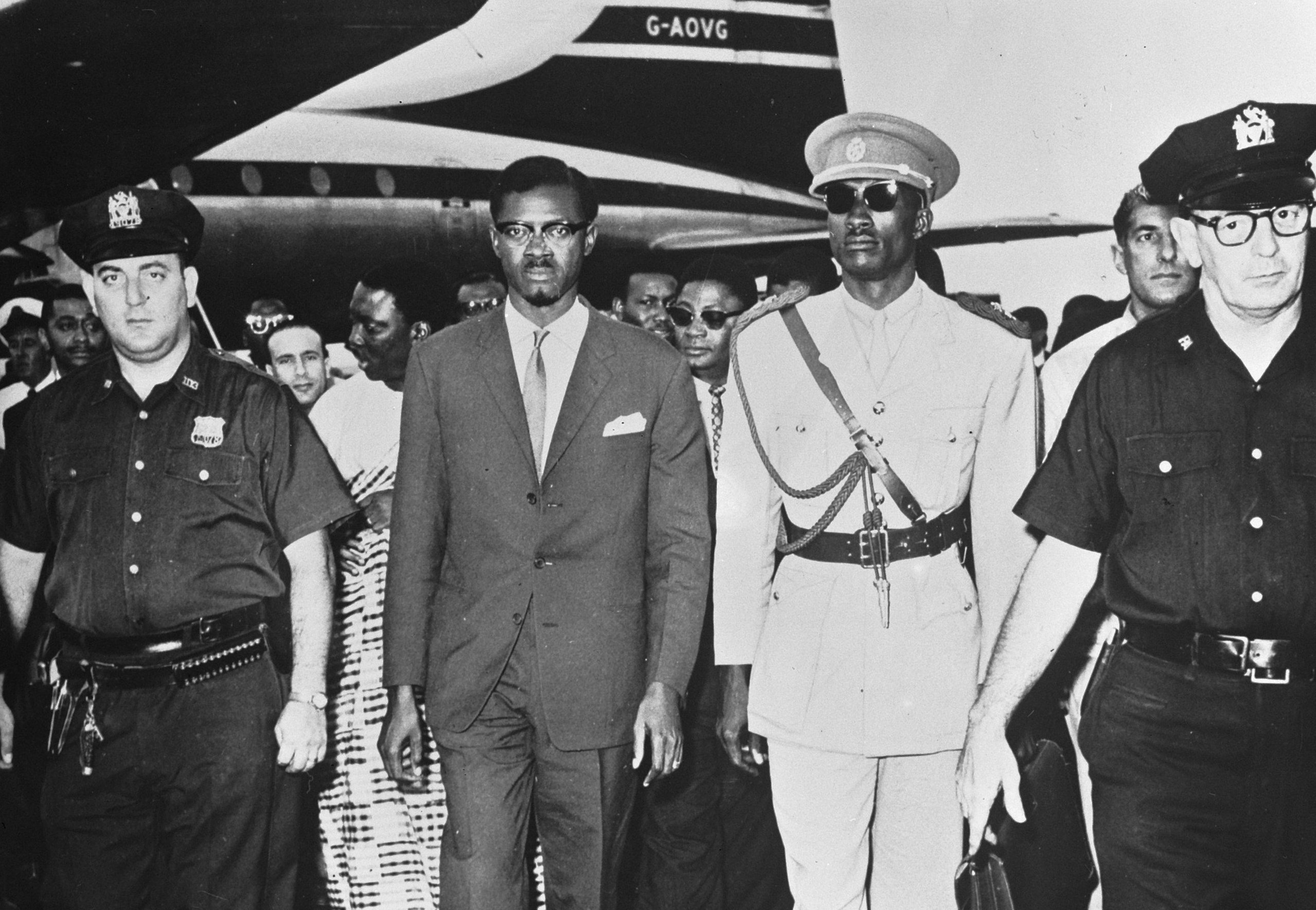

Determined to personally articulate his government's position, Lumumba traveled to New York City to address the United Nations. Before his departure, he announced an economic agreement with the U.S. businessman who established the Congo International Management Corporation (CIMCO), a development corporation intended to invest in and manage certain economic sectors (though it still required parliamentary ratification). He also declared that Soviet aid was "no longer necessary" and expressed his intention to seek technical assistance from the United States. Lumumba and his delegation arrived in New York on 24 July after brief stops in Accra and London. African diplomats, keen for successful meetings, convinced Lumumba to postpone major economic agreements until Congo achieved greater stability. Over three days (24, 25, 26 July), Lumumba met with Dag Hammarskjöld and other UN Secretariat staff, focusing on the withdrawal of Belgian troops and options for technical assistance. In a press conference, Lumumba reaffirmed his government's commitment to "positive neutralism."

On 27 July, Lumumba traveled to Washington, D.C., where he met with the US Secretary of State and appealed for financial and technical assistance. The U.S. government, however, stated it would only provide aid through the UN. The next day, a telegram from Gizenga detailed a clash between Belgian and Congolese forces at Kolwezi. Lumumba felt the UN was obstructing his efforts to expel Belgian troops and defeat Katangan rebels. On 29 July, Lumumba sought help in Ottawa, Canada, but was rebuffed, with Canada also insisting on channeling aid through the UN. Frustrated, Lumumba met with the Soviet ambassador in Ottawa to discuss military equipment donations. Upon his return to New York, his attitude towards the UN was restrained. The U.S. government's stance had grown more negative due to reports of violence by ANC soldiers and Belgian scrutiny, as Belgium regarded Lumumba as communist, anti-white, and anti-Western, a view many other Western governments credited.

Frustrated by the UN's perceived inaction regarding Katanga, Lumumba delayed his return to the Congo, opting instead to tour several African states from 2 to 8 August. This tour aimed to pressure Hammarskjöld or secure bilateral military support to suppress Katanga. He was well-received in Tunisia, Morocco, Guinea, Ghana, Liberia, and Togo, issuing joint communiques with their heads of state. Guinea and Ghana pledged independent military support, while others favored working through the UN. In Ghana, Lumumba signed a secret agreement with President Nkrumah for a "Union of African States" centered in Léopoldville, envisioning a republican federation. They planned an African summit in Léopoldville from 25 to 30 August to further discuss this. Lumumba returned to the Congo confident in potential African military and technical assistance, which put him at odds with Hammarskjöld's goal of funneling support through ONUC, as Lumumba and some ministers were wary of UN functionaries who would not directly answer to their authority.

On 9 August, Lumumba declared a state of emergency across the Congo and issued several orders to reassert his authority. These included outlawing associations without government sanction, asserting the right to ban publications that discredited the administration, and nationalizing local Belga offices to create the Agence Congolaise de PresseFrench (Congolese Press Agency), aiming to eliminate biased reporting and better communicate government policy. Another order required six days' advance approval for public gatherings. On 16 August, Lumumba announced the implementation of a régime militaire spécialFrench (special military regime) for six months.

Throughout August, Lumumba increasingly relied on a trusted inner circle of officials and ministers, including Maurice Mpolo, Joseph Mbuyi, Kashamura, Gizenga, and Antoine Kiwewa, withdrawing from his full cabinet. His office was disorganized, and his chef de cabinetFrench, Damien Kandolo, was often absent and secretly working for the Belgian government. Lumumba became deeply suspicious due to constant rumors and reports from informants. His press secretary, Serge Michel, even enlisted Belgian telex operators to provide him with copies of all outgoing journalistic dispatches to keep him informed.

Lumumba immediately ordered Congolese troops to suppress the rebellion in secessionist South Kasai, which was strategically vital due to its rail links for a potential campaign in Katanga. The operation succeeded, but it tragically devolved into ethnic violence, with the army involved in massacres of Luba civilians. The people and politicians of South Kasai held Lumumba personally responsible for the army's actions. Kasa-Vubu publicly declared that only a federalist government could bring peace and stability to the Congo, thereby breaking his fragile alliance with Lumumba and shifting political sentiment away from Lumumba's unitary state vision. Ethnic tensions against Lumumba rose, particularly around Léopoldville, and the powerful Catholic Church openly criticized his government. Even with South Kasai subdued, Congo lacked the strength to retake Katanga. Lumumba's African conference in Léopoldville (25-31 August) failed to attract foreign heads of state or military pledges. He again demanded UN peacekeeping assistance, threatening Soviet intervention if refused. The UN denied his request, making a direct Soviet intervention seem increasingly likely.

5. Dismissal

The escalating political crisis and Lumumba's perceived radicalism led to a decisive power struggle, culminating in his dismissal and the subsequent military coup.

5.1. Kasa-Vubu's revocation order

President Kasa-Vubu, fearing a Lumumbist coup, announced on the evening of 5 September that he had dismissed Lumumba and six of his ministers. He cited the massacres in South Kasai and Lumumba's involvement with the Soviets as reasons. Lumumba, upon hearing the broadcast, went to the national radio station, which was under UN guard. Despite orders to bar his entry, UN troops allowed him in, as they had no specific instructions to use force against him. Lumumba denounced his dismissal as illegitimate, labeling Kasa-Vubu a traitor and declaring him deposed. Kasa-Vubu's action was legally invalid because he had not secured the approval of any responsible ministers. Lumumba highlighted this in a letter to Hammarskjöld and a radio broadcast on 6 September. Later that day, Kasa-Vubu obtained the countersignatures of Albert Delvaux, Minister Resident in Belgium, and Justin Marie Bomboko, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and re-announced Lumumba's dismissal over Brazzaville radio.

Lumumba and his loyal ministers ordered the arrest of Delvaux and Bomboko for countersigning the dismissal order. Bomboko sought refuge in the presidential palace, guarded by UN peacekeepers, but Delvaux was detained at the Prime Minister's residence. Lumumba later denied authorizing the arrests and issued an apology to the Chamber of Deputies. The Chamber convened to discuss Kasa-Vubu's order and hear Lumumba's reply. Delvaux made an unexpected appearance, denounced his arrest, and resigned, receiving applause from the opposition. Lumumba then delivered his speech, avoiding a direct personal attack on Kasa-Vubu. Instead, he accused obstructionist politicians and ABAKO of using the presidency to disguise their activities. He noted Kasa-Vubu had never criticized the government before and portrayed their relationship as cooperative. He criticized Delvaux and Minister of Finance Pascal Nkayi for their role in UN Geneva negotiations and for failing to consult the government. Lumumba concluded by analyzing the Loi FondamentaleFrench (Basic Law) and requested Parliament to form a "commission of sages" to address Congo's problems.

The Chamber, at its presiding officer's suggestion, voted to annul both Kasa-Vubu's and Lumumba's declarations of dismissal, 60 to 19. The following day, Lumumba delivered a similar speech to the Senate, which passed a vote of confidence in his government, 49 to zero with seven abstentions. Article 51 of the constitution granted Parliament the "exclusive privilege" to interpret the constitution. However, with the rupture of relations with Belgium in July, the Belgian Conseil d'État, which would normally resolve such constitutional questions, was no longer available. This left no authoritative interpretation or mediation for the dispute. Numerous African diplomats and the newly appointed ONUC head, Rajeshwar Dayal, attempted to reconcile the president and prime minister but failed. On 13 September, Parliament held a joint session of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Despite being short of a quorum, they voted to grant Lumumba emergency powers.

5.2. Mobutu's coup

On 14 September, Mobutu announced over the radio that he was launching a "peaceful revolution" to resolve the political impasse. He declared the neutralization of the President, Lumumba's and Iléo's respective governments, and Parliament until 31 December. He stated that "technicians" would manage the administration while politicians resolved their differences, and further declared that all Eastern Bloc countries should close their embassies. Lumumba was surprised by the coup, which was reportedly encouraged and supported by Belgium and the United States. That evening, Lumumba went to Camp Leopold II to try and persuade Mobutu to change his mind. He spent the night there but was attacked in the morning by Luba soldiers, who blamed him for the atrocities in South Kasaï. A Ghanaian ONUC contingent managed to extract him, but his briefcase was left behind. His political opponents recovered it and published documents it supposedly contained, including letters from Nkrumah, appeals for support addressed to the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China, a memorandum dated 16 September declaring the presence of Soviet troops within one week, and a letter dated 15 September from Lumumba to the provincial presidents (Tshombe excepted) entitled "Measures to be applied during the first stages of the dictatorship." Some of these papers were genuine, while others, particularly the memorandum and the letter to the provincial presidents, were almost certainly forgeries.

Despite the coup, African diplomats continued to work towards a reconciliation between Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu. According to Ghanaian accounts, a verbal agreement for closer cooperation between the Head of State and the government was put into writing. Lumumba signed it, but Kasa-Vubu unexpectedly refused to reciprocate. The Ghanaians suspected Belgian and United States influence. Kasa-Vubu was eager to reintegrate Katanga into the Congo through negotiation, and Tshombe had stated he would not participate in any discussions with a government that included the "communist" Lumumba.

After consulting with Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba, Mobutu announced a round table conference to discuss Congo's political future. However, Lumumba, from his official residence, continued to act as if he were still prime minister. He held meetings with his government members, senators, deputies, and political supporters, and issued public statements. He frequently left his residence to visit restaurants in the capital, asserting his continued authority. Frustrated by Lumumba's actions and facing intense political pressure, Mobutu, by the end of the month, abandoned reconciliation efforts and aligned with Kasa-Vubu. He ordered ANC units to surround Lumumba's residence, but a cordon of UN peacekeepers prevented his arrest, confining Lumumba to his home. On 7 October, Lumumba announced the formation of a new government, including Bolikango and Kalonji, but later proposed that the UN supervise a national referendum to resolve the government split.

On 24 November, the UN voted to recognize Mobutu's new delegates to the United Nations General Assembly, disregarding Lumumba's original appointees. Lumumba resolved to join Deputy Prime Minister Antoine Gizenga in Stanleyville and lead a campaign to regain power. On 27 November, he left the capital in a convoy of nine cars with Rémy Mwamba, Pierre Mulele, his wife Pauline, and his youngest child. Instead of rushing to the Orientale Province border, where loyal Gizenga soldiers awaited, Lumumba delayed by touring villages and conversing with locals. On 1 December, Mobutu's troops caught up with his party as it crossed the Sankuru River in Lodi. Lumumba and his advisers had crossed to the far side, but his wife and child were captured on the bank. Fearing for their safety, Lumumba took the ferry back, against the advice of Mwamba and Mulele, who bid him farewell, fearing they would never see him again. Mobutu's men arrested him. He was moved to Port Francqui the next day and flown back to Léopoldville. Mobutu claimed Lumumba would be tried for inciting army rebellion and other crimes.

The Secretary-General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, appealed to Kasa-Vubu, requesting that Lumumba be treated according to due process. The Soviet Union denounced Hammarskjöld and the First World as responsible for Lumumba's arrest and demanded his release, immediate restoration as head of the Congo government, disarming of Mobutu's forces, and immediate evacuation of Belgians from the Congo. The Soviets also requested Hammarskjöld's immediate resignation, the arrests of Mobutu and Tshombe, and the withdrawal of UN peacekeeping forces. Hammarskjöld, responding to Soviet criticism, stated that if UN forces withdrew, "I fear everything will crumble." The threat to the UN's mission intensified with the announced withdrawal of contingents from Yugoslavia, the United Arab Republic, Ceylon, Indonesia, Morocco, and Guinea. The pro-Lumumba resolution was defeated on 14 December 1960 by a vote of 8-2. On the same day, a Western resolution granting Hammarskjöld increased powers to manage the Congo situation was vetoed by the Soviet Union.

6. Assassination

The circumstances surrounding Patrice Lumumba's death are deeply controversial, revealing a calculated execution orchestrated by his political adversaries with significant foreign backing.

6.1. Execution

Lumumba was first sent on 3 December 1960 to Thysville military barracks, Camp Hardy, located 93 mile (150 km) (about 100 mile) from Léopoldville. He was accompanied by Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, two political associates who had planned to assist him in establishing a new government. Under Mobutu's orders, they were poorly fed by the prison guards. In his last documented letter, Lumumba wrote to Rajeshwar Dayal: "In a word, we are living amid absolutely impossible conditions; moreover, they are against the law."

On the morning of 13 January 1961, discipline at Camp Hardy faltered as soldiers demanded payment, receiving a total of 400.00 K FC (8.00 K USD) from the Katanga Cabinet. Some soldiers supported Lumumba's release, while others considered him dangerous. Kasa-Vubu, Mobutu, Foreign Minister Justin Marie Bomboko, and Head of Security Services Victor Nendaka Bika personally arrived at the camp to negotiate with the troops. Although conflict was avoided, it became evident that holding such a controversial prisoner in the camp posed too great a risk. Consequently, Harold Charles d'Aspremont Lynden, the last Belgian Minister of the Colonies, ordered that Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okito be transferred to the State of Katanga.

Lumumba was forcibly restrained on the flight to Elisabethville on 17 January 1961. Upon arrival, he and his associates were taken to the Brouwez House, where they were brutally beaten and tortured by Katangan officers and Belgian soldiers. During this time, President Tshombe and his cabinet deliberated their fate. Later that same night, Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okito were driven to an isolated location. Three firing squads, commanded by Belgian contract officer Julien Gat, had been assembled. The orders to murder Lumumba were issued by Katangan leaders, but the final stage of the execution was personally overseen by Belgian contractors, including Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure. Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okito were individually tied to a tree and shot. The execution is believed to have occurred on 17 January 1961, between 21:40 and 21:43, according to a later Belgian parliamentary inquiry. Tshombe, two other ministers, and four Belgian officers under the command of the Katangan authorities were present. The bodies were subsequently thrown into a shallow grave.

6.2. Post-mortem handling and announcement

The morning after the execution, on the orders of Katangan Interior Minister Godefroid Munongo, who sought to eliminate the bodies and prevent the creation of a burial site, Belgian Gendarmerie officer Gerard Soete and his team exhumed and dismembered the corpses. They then dissolved the remains in concentrated sulfuric acid, while any remaining bones were ground and scattered. This act was intended to ensure no trace of Lumumba's body remained.

No official statement regarding Lumumba's death was released for three weeks, despite persistent rumors. Katangan Secretary of State of Information Lucas Samalenge was among the first to reveal Lumumba's death on 18 January, reportedly telling patrons at the Le Relais bar in Élisabethville that Lumumba was dead and that he had kicked his corpse, repeating the story until police intervened. On 10 February, radio reports falsely announced that Lumumba and two other prisoners had escaped. His death was formally announced over Katangan radio on 13 February, with the fabricated claim that he was killed by enraged villagers three days after escaping from Kolatey prison farm.

Following the announcement of Lumumba's death, widespread street protests erupted in several European countries. In Belgrade, protesters sacked the Belgian embassy and clashed with police. In London, a crowd marched from Trafalgar Square to the Belgian embassy, where a letter of protest was delivered, and confrontations with police ensued. In New York City, a demonstration at the United Nations Security Council turned violent, spilling into the streets and resulting in injuries to UN guards, newsmen, and protesters. Fights between white and black individuals broke out outside the UN building, and a large protest march into Times Square was halted by mounted police.

7. Foreign involvement in his execution

The assassination of Patrice Lumumba was a complex event deeply influenced by the geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War, with significant involvement from Belgium, the United States, and the United Kingdom, driven by fears of his perceived communist sympathies and potential threat to Western interests.

The ongoing Cold War significantly shaped the perceptions of Lumumba by both Belgium and the United States. They feared he was increasingly susceptible to communist influence due to his appeals for Soviet aid. However, journalist Sean Kelly, a correspondent for the Voice of America at the time, argued that Lumumba sought Soviet assistance not out of communist ideology, but because he believed the Soviet Union was the only power willing to support his government's efforts to defeat Belgian-backed separatists and eliminate colonial influence. Lumumba had initially sought help from the United States. For his part, Lumumba consistently denied being a communist, stating that he found colonialism and communism equally deplorable, and publicly advocated for neutrality between the East and West.

7.1. Belgian involvement

On 18 January, panicked by reports that the burial of the three bodies had been observed, members of the execution team exhumed the remains and moved them for reburial near the border with Northern Rhodesia. Belgian Police Commissioner Gerard Soete later confessed in multiple accounts that he and his brother, along with Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure, led the initial exhumation. On the afternoon and evening of 21 January, Commissioner Soete and his brother dug up Lumumba's corpse a second time, dismembered it with a hacksaw, and dissolved it in concentrated sulfuric acid. In a 1999 Belgian television interview about the assassination, Soete even displayed a bullet and two teeth, including a gold-capped one, that he claimed to have saved from Lumumba's body.

The 2001 Belgian Commission investigating Lumumba's assassination concluded that Belgium desired Lumumba's arrest, was not particularly concerned with his physical well-being, and, despite being informed of the danger to his life, took no action to prevent his death. However, the report concluded that Belgium had not directly ordered Lumumba's execution. In February 2002, the Belgian government formally apologized to the Congolese people, admitting "moral responsibility" and "an irrefutable portion of responsibility in the events that led to the death of Lumumba."

Lumumba's execution was carried out by a firing squad led by Belgian mercenary Julien Gat. Katangan Police Commissioner Verscheure, a Belgian, had overall command of the execution site. The separatist Katangan regime was heavily supported by the Belgian mining conglomerate Union Minière du Haut-Katanga. In the early 21st century, documents uncovered by Ludo De Witte challenged the notion that Belgian officers in Katanga only followed Katangan orders. These documents revealed that Belgian officers were also adhering to Belgian government policy and orders. Specifically, Belgian Minister of African Affairs Harold Charles d'Aspremont Lynden, who was tasked with organizing Katanga's secession, sent a cable on 6 October 1960 stating that the policy from then on would be the "definitive elimination of Patrice Lumumba." Lynden had also insisted on 15 January 1961 that an imprisoned Lumumba be sent to Katanga, which was effectively a death sentence.

7.2. United States involvement

The 2001 report by the Belgian Commission detailed previous U.S. and Belgian plots to kill Lumumba, including a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)-sponsored attempt to poison him. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized Lumumba's assassination in 1960. While the plot to poison him was ultimately abandoned, CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb, a key figure in the plan, developed various toxic materials for the assassination. In September 1960, Gottlieb brought a vial of poison to the Congo, and CIA Station Chief Larry Devlin devised plans to administer it via Lumumba's toothbrush or food. The plot failed because Devlin's agent was unable to carry it out, and the replacement agent, Justin O'Donnell, refused to participate.

According to Madeleine G. Kalb's book Congo Cables, numerous communications from Devlin at the time urged Lumumba's elimination. Michael P. Holt noted that Devlin also helped direct the search for Lumumba and arranged his transfer to the separatist authorities in Katanga. John Stockwell, a CIA officer in the Congo who later became a CIA station chief, wrote in 1978 that the CIA base chief in Elizabethville was in direct contact with Lumumba's killers on the night of his execution. Stockwell also claimed a CIA agent had a body in the trunk of his car that they were trying to dispose of, and believed Devlin knew more than anyone else about the murder.

The inauguration of John F. Kennedy in January 1961 caused apprehension among Mobutu's faction and within the CIA, as they feared the incoming Kennedy administration would favor the imprisoned Lumumba. While awaiting his inauguration, Kennedy had come to believe that Lumumba should be released from custody, though not reinstated to power. Lumumba was killed three days before Kennedy's inauguration on 20 January, though Kennedy did not learn of the killing until 13 February. White House photographer Jacques Lowe captured Kennedy's horror-struck reaction upon receiving the news, quoting him groaning, "Oh, no."

The 1975 Church Committee found that CIA chief Allen Dulles had ordered Lumumba's assassination as "an urgent and prime objective." Declassified CIA cables mentioned in the Church report and Kalb's book detail two specific CIA plots to murder Lumumba: the poison plot and a shooting plot. The Committee later concluded that while the CIA had conspired to kill Lumumba, it was not directly involved in the actual murder.

In the early 21st century, declassified documents further revealed the CIA's plots to assassinate Lumumba. These documents indicate that Congolese leaders who overthrew Lumumba and transferred him to Katangan authorities, including Mobutu Sese Seko and Joseph Kasa-Vubu, received money and weapons directly from the CIA. These disclosures also showed that the U.S. government at the time considered Lumumba a communist and feared him due to the perceived threat of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. In 2000, a newly declassified interview with Robert Johnson, the minutekeeper of the U.S. National Security Council, revealed that President Eisenhower had said "something [to CIA chief Allen Dulles] to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated." In 2013, the U.S. State Department admitted that President Eisenhower discussed plans to assassinate Lumumba at an NSC meeting on 18 August 1960. However, documents released in 2017 suggested that an American role in Lumumba's murder was only under consideration by the CIA. CIA Chief Allan Dulles had allocated 100.00 K USD for the act, but the plan was not carried out.

7.3. United Kingdom involvement

In June 2001, newly discovered documents by Ludo De Witte revealed that while the U.S. and Belgium actively plotted to murder Lumumba, the British government secretly desired his removal, believing he posed a serious threat to British interests in the Congo, particularly mining facilities in Katanga. Howard Smith, who would later become head of MI5 in 1979, stated, "I can see only two possible solutions to the problem. The first is the simple one of ensuring Lumumba's removal from the scene by killing him. This should solve the problem."

In April 2013, in a letter to the London Review of Books, British parliamentarian David Lea reported a conversation with MI6 officer Daphne Park shortly before her death in March 2010. Park had been stationed in Léopoldville at the time of Lumumba's death and later served as a semi-official spokesperson for MI6 in the House of Lords. According to Lea, when he mentioned "the uproar" surrounding Lumumba's abduction and murder and the theory that MI6 might have been involved, Park replied, "We did. I organised it." The BBC reported that "Whitehall sources" subsequently described the claims of MI6 involvement as "speculative."

7.4. Repatriation of his remains

On 30 June 2020, Lumumba's daughter, Juliana Lumumba, directly appealed to Philippe, King of the Belgians, in a letter requesting the return of "the relics of Patrice Émery Lumumba to the ground of his ancestors." She described her father as "a hero without a grave," questioning why his remains were "condemned to remain a soul forever wandering, without a grave to shelter his eternal rest." On 10 September 2020, a Belgian judge ruled that Lumumba's remains-which by then consisted only of a single gold-capped tooth (Gerard Soete had lost the other tooth between 1999 and 2020)-must be returned to his family.

In May 2021, Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi announced the repatriation of Lumumba's last remains, though the handover ceremony was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On 9 June 2022, during a speech to the DRC parliament, King Philippe reiterated regrets for Belgium's colonial past, describing Belgian rule as a "regime... of unequal relations, unjustifiable in itself, marked by paternalism, discrimination and racism" that "led to violent acts and humiliations."

On 20 June, Lumumba's children received their father's remains during a ceremony at Egmont Palace in Brussels, where the federal prosecutor formally handed custody to the family. Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo apologized on behalf of the Belgian government for its role in Lumumba's assassination, stating: "For my part, I would like to apologise here, in the presence of his family, for the way in which the Belgian government influenced the decision to end the life of the country's first prime minister." He added, "A man was murdered for his political convictions, his words, his ideals." Subsequently, a full-sized coffin, draped in the Congolese flag, was publicly displayed for the Congolese and wider African diaspora in Belgium to pay their respects before the return. A special mausoleum was constructed in Kinshasa to house his remains. The government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared three days of national mourning. The burial coincided with the 61st anniversary of his famous independence day speech on 30 June 2022. An investigation by Belgian prosecutors for "war crimes" related to Lumumba's murder remains ongoing. On 18 November 2024, the mausoleum was vandalized and Lumumba's coffin broken, though the interior ministry confirmed his tooth was safe.

8. Political ideology

Patrice Lumumba did not articulate a rigid, comprehensive political or economic platform, yet his ideology was deeply rooted in a powerful vision for the Congo. According to Patricia Goff, Lumumba was the first Congolese leader to articulate a narrative of the Congo that fundamentally challenged traditional Belgian colonial views. He emphasized the profound suffering endured by the indigenous population under European rule, distinguishing himself from his contemporaries who often confined their discussions to specific ethnic or regional interests. Lumumba's narrative encompassed all Congolese people, offering a basis for national identity founded on shared experiences of colonial victimization, as well as the inherent dignity, humanity, strength, and unity of the Congolese people.

At the core of Lumumba's beliefs was an ideal of humanism that embraced egalitarianism, social justice, liberty, and the recognition of fundamental rights. He viewed the state as a proactive advocate for the public welfare, believing its intervention in Congolese society was essential to ensure equality, justice, and social harmony. His political convictions were fundamentally shaped by Congolese nationalism, which sought to unify the diverse ethnic groups into a single, cohesive nation. This was complemented by a strong commitment to pan-Africanism, advocating for the solidarity and liberation of all African nations from colonial influence. He also espoused social progressivism, aiming for societal advancement and improved living conditions for all Congolese citizens. Lumumba publicly professed his personal preference for neutrality between the East and West, stating that he found colonialism and communism equally deplorable.

9. Legacy and evaluation

Patrice Lumumba's legacy is complex and multifaceted, marked by enduring impact despite his brief time in power and controversial death. He is widely remembered as a symbol of anti-colonial struggle and African self-determination.

9.1. Historiography

Full accounts of Lumumba's life and death began to appear within weeks of his demise, with several highly partisan biographies published in the years following 1961. Early works on the Congo Crisis also extensively discussed Lumumba. For decades after his death, misconceptions about Lumumba persisted among both his supporters and critics, and serious academic study of him waned. Academic discussion of his legacy was largely limited until the later stages of Mobutu's rule in the Congo, with Mobutu's opening of the country to multi-party politics in 1990 reviving interest in Lumumba's death.

Belgian literature in the decades following the Congo Crisis often portrayed Lumumba as incompetent, demagogic, aggressive, ungrateful, undiplomatic, and communist. Most Africanists of the 20th century, such as Jean-Claude Willame, viewed Lumumba as an intransigent, unrealistic idealist lacking a tangible program, who alienated his contemporaries and the Western world with radical anti-colonial rhetoric. They largely held him responsible for the political crisis that led to his downfall. However, a few writers, like Jean-Paul Sartre, while acknowledging the perceived unattainability of Lumumba's goals in 1960, nevertheless saw him as a martyr for Congolese independence, a victim of Western interests and events beyond his control. Sociologist Ludo De Witte argues that both of these perspectives overstate Lumumba's political weaknesses and isolation.

A conventional narrative of Lumumba's premiership and downfall emerged, depicting him as an uncompromising radical who provoked his own murder by angering domestic separatists. Within Belgium, the popular narrative implicated some Belgian individuals in his death but stressed that they were acting "under orders" from African figures and that the Belgian government was uninvolved. Some Belgian circles even propagated the idea that the United States, particularly the CIA, had orchestrated the killing.

This narrative was significantly challenged by Ludo De Witte's 2001 work, The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba, which presented evidence that the Belgian government, with the complicity of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the UN, bore substantial responsibility for his death. Media discussion of Lumumba, spurred by the book's release and the 2000 feature film Lumumba, became significantly more positive afterward. A new narrative emerged, attributing Lumumba's death to Western espionage and emphasizing the threat his charismatic appeal posed to Western interests. Lumumba's role in the Congolese independence movement is well-documented, and he is typically recognized as its most important and influential leader. His achievements are usually celebrated as the work of him as an individual, rather than that of a larger movement.

9.2. Political impact

Patrice Lumumba's political legacy remains debated due to his short time in office, rapid removal from power, and controversial death. His downfall was a significant setback for African nationalist movements, and he is often remembered primarily for his assassination.

Numerous American historians have identified his death as a major factor contributing to the radicalization of the American civil rights movement in the 1960s. Many African-American activist organizations and publications used public commentary on his death to articulate their ideology. Popular memory of Lumumba has often simplified his politics, reducing him to a powerful symbol. Within the Congo, Lumumba is primarily portrayed as a symbol of national unity, while internationally he is often cast as a pan-Africanist and anti-colonial revolutionary.

The ideological legacy of Lumumba is known as LumumbismeFrench (French for Lumumbism). Rather than a complex doctrine, it is generally framed as a set of fundamental principles: nationalism, Pan-Africanism, non-alignment, and social progressivism. Mobutism, the ideology of Mobutu Sese Seko, ironically built upon some of these principles. Congolese university students, who had shown little respect for Lumumba before independence, embraced LumumbismeFrench after his death. According to political scientist Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, Lumumba's "greatest legacy... for the Congo is the ideal of national unity." Nzongola-Ntalaja further posited that, due to Lumumba's high praise for the independence movement and his efforts to end the Katangese secession, "the people of the Congo are likely to remain steadfast in their defense of national unity and territorial integrity, come hell or high water." Political scientist Ali Mazrui noted, "It looks as if the memory of Lumumba may contribute more to the 'oneness' of the Congolese than anything Lumumba himself actually did while he was still alive."

Following the suppression of the rebellions in 1964 and 1965, most Lumumbist ideology was confined to isolated groups of intellectuals who faced repression under Mobutu's regime. By 1966, popular devotion to him had declined outside the political elite. According to Africanist Bogumil Jewsiewicki, by 1999, "the only faithful surviving Lumumbist nucleus is located in Sankuru and Maniema, and its loyalty is questionable (more ethnical, regional, and sentimental than ideological and political)." Lumumba's image remained unpopular in southern Kasai for years after his death, as many Baluba remembered the violent atrocities committed against their people during the military campaign he ordered in August 1960.

At least a dozen Congolese political parties have claimed to inherit Lumumba's political and spiritual heritage. Despite this, few have successfully incorporated his ideas into a coherent political program. Most of these parties have garnered little electoral support, though Gizenga's Parti Lumumbiste UnifiéFrench was represented in the Congolese coalition government formed under President Joseph Kabila in 2006. Aside from student groups, Lumumbist ideals play only a minor role in current Congolese politics. Congolese presidents Mobutu, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, and Joseph Kabila all claimed to inherit Lumumba's legacy and paid tribute to him early in their tenures.

9.3. Martyrdom

The circumstances of Patrice Lumumba's death have frequently led to his portrayal as a martyr. While his demise triggered immediate mass demonstrations abroad and the rapid formation of a martyr image internationally, the immediate reaction to his death within the Congo was not uniform. While the Tetela, Songye, and Luba-Katanga peoples created folk songs of mourning for him, these were groups that had been politically allied with him. At the time, Lumumba was unpopular in large segments of the Congolese populace, particularly in the capital, Bas-Congo, Katanga, and South Kasai. Some of his actions and his portrayal as a communist by his detractors had also generated disaffection in the army, civil service, labor unions, and the Catholic Church. Lumumba's reputation as a martyr in the collective memory of the Congolese was only cemented later, partly due to initiatives by Mobutu.

In Congolese collective memory, it is widely believed that Lumumba was killed through Western machinations because he defended the Congo's self-determination. His killing is viewed as a symbolic moment when the Congo lost its dignity in the international realm and its ability to determine its future, which has since been perceived as controlled by the West. Lumumba's determination to pursue his goals is extrapolated onto the Congolese people as their own; thus, securing Congo's dignity and self-determination is seen as ensuring their "redemption" from victimization by Western powers. Historian David Van Reybrouck wrote, "In no time Lumumba became a martyr of decolonisation... He owed this status more to the horrible end of his life than to his political successes." Journalist Michela Wrong remarked that "He really did become a hero after his death, in a way that one has to wonder if he would have been such a hero if he had remained and run the country and faced all the problems that running a country as big as Congo would have inevitably brought." Drama scholar Peit Defraeya wrote, "Lumumba as a dead martyr has become a more compelling figure in liberationist discourse than the controversial live politician." Historian Pedro Monaville noted that "his globally iconic status was not commensurate with his more complex legacy in [the] Congo." The cooptation of Lumumba's legacy by Congolese presidents and state media has generated doubts in the Congolese public about his reputation.

10. Commemoration and tributes

Patrice Lumumba has been honored in various ways globally, reflecting his enduring status as a symbol of anti-colonialism and African liberation.

In 1961, Cyrille Adoula became Prime Minister of the Congo and shortly after laid a wreath of flowers at an impromptu monument for Lumumba in Stanleyville. When Moïse Tshombe became Prime Minister in 1964, he also visited Stanleyville and paid similar tribute. On 30 June 1966, Mobutu officially rehabilitated Lumumba's image, proclaiming him a "national hero." Mobutu announced several measures to commemorate Lumumba, though few were fully implemented, apart from the release of a banknote bearing his visage the following year. This banknote was unique during Mobutu's rule as it was the only paper money featuring a leader other than the incumbent president. In subsequent years, state mention of Lumumba declined, and Mobutu's regime viewed unofficial tributes with suspicion. Following Laurent-Désiré Kabila's seizure of power in the 1990s, a new series of Congolese francs was issued, again featuring Lumumba's image.

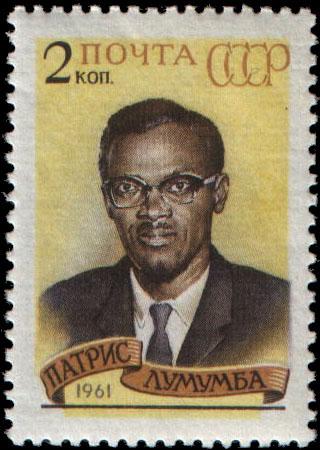

In January 2003, Joseph Kabila, who succeeded his father as president, inaugurated a statue of Lumumba in Kinshasa. In Guinea, Lumumba was featured on a coin and two regular banknotes, an unprecedented occurrence in modern national currency as images of foreigners are typically reserved for commemorative issues. As of 2020, Lumumba has been featured on 16 different postage stamps. Many streets and public squares around the world have been named after him. The Peoples' Friendship University of Russia in Moscow was renamed "Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University" in 1961, though it was renamed again in 1992 before reverting to its Lumumba name in 2023. In 2013, the planned community of Lumumbaville was named in his honor.

11. Lumumba in popular culture

Patrice Lumumba is widely regarded as one of the "fathers of independence" of the Congo, and his image frequently appears in social media and serves as a rallying cry in demonstrations of social defiance. His figure is prevalent in art and literature, particularly outside of the Congo. He was referenced by numerous African-American writers of the American civil rights movement, especially in their post-civil rights era works. Malcolm X famously declared him "the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent."

Among the most prominent works featuring him are Aimé Césaire's 1966 play, Une saison au Congo, and Raoul Peck's 1992 documentary Lumumba, la mort d'un prophète and his 2000 feature film, Lumumba. There is also an Italian 1968 feature film, Seduto alla sua destra (literally 'Sitting to his right') by Valerio Zurlini, which portrays the last days of the character Maurice Lalubi (played by Woody Strode), based on Patrice Lumumba, as a Passion of Christ narrative. This movie was included in the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, which was ultimately canceled due to the events of May 68 in France.

Numerous songs and plays have been dedicated to Lumumba. Many praise his character, often contrasting it with the alleged irresponsible and undisciplined nature of the Congolese people. Congolese musicians Franco Luambo and Joseph Kabasele both wrote tribute songs to Lumumba shortly after his death. Other musical works mentioning him include "Lumumba" by Miriam Makeba, "Done Too Soon" by Neil Diamond, and "Waltz for Lumumba" by the Spencer Davis Group. His name is also frequently mentioned in rap music, with artists such as Arrested Development, Nas, David Banner, Black Thought, Damso, Baloji, Médine, and Sammus incorporating him into their work.

In popular painting, Lumumba is often associated with notions of sacrifice and redemption, sometimes even portrayed as a messiah, with his downfall depicted as his passion. Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu painted a series chronicling Lumumba's life and career. Lumumba is relatively absent from Congolese writing, and when he does appear, it is often through subtle or ambiguous references. Congolese authors Sony Lab'ou Tansi's fictional Parentheses of Blood and Sylvain Bemba's Léopolis both feature characters with strong similarities to Lumumba. In written tributes to Mobutu, Lumumba is typically portrayed as an adviser to the former. Writer Charles Djungu-Simba observed, "Lumumba is rather considered as a vestige of the past, albeit an illustrious past." His surname is also used to identify a long drink made of hot or cold chocolate and rum.