1. Life

Niijima Yae's life was marked by her resilience, adaptability, and a pioneering spirit that consistently challenged the traditional roles of women in Japan during a period of immense social and political upheaval.

1.1. Early Life and Background

Yamamoto Yae was born on December 1, 1845, in Aizu, Mutsu Province (present-day Fukushima Prefecture), Japan. She was the daughter of Yamamoto Gonpachi (山本権八Japanese), a samurai who served as one of the official gunnery instructors for the Aizu Domain, and his wife Saku. Her family's stipend was 22 koku with an additional allowance for four people. The Yamamoto family claimed direct descent from Yamamoto Kansuke (山本勘助Japanese), a renowned strategist and retainer of the Takeda clan. Yae had an elder brother, Yamamoto Kakuma (山本覚馬Japanese). From a young age, Yae showed a keen interest in firearms, a highly unusual pursuit for a woman during the Bakumatsu period, and developed considerable skill in gunnery under her father's tutelage. In 1865, she married Shonosuke Kawasaki (川崎尚之助Japanese), a Rangaku (Dutch Studies) scholar from the Izushi Domain (present-day Toyooka) who served as a professor at the domain's school, Nisshinkan.

1.2. Aizu Period and Boshin War

Yae's gunnery skills proved crucial during the Boshin War, which erupted in 1868. As the Meiji government forces advanced northward after taking Edo, they attacked Aizu, a stronghold of the Tokugawa Shogunate supporters. During the Battle of Aizu, Yae actively participated in the defense of Aizuwakamatsu Castle (会津若松城Japanese). She cut her hair short and dressed in male attire, fighting alongside the Aizu warriors. She wielded a Spencer repeating rifle and a katana, bravely defending the castle. It is noted that her Spencer carbine was reportedly the only one of its kind in the entire Aizu Domain, and she fought using the 100 rounds of ammunition she had brought herself. Yae was recognized as an excellent marksman; it is said that she severely wounded Ōyama Iwao (大山厳Japanese), the commander of the Satsuma Domain's Second Artillery Unit, forcing him to withdraw from the front lines.

After the surrender of the Aizu Domain, Yae took shelter in the nearby Yonezawa Domain in Yonezawa, Yamagata, where she stayed for approximately one year. Her first husband, Shonosuke, was captured as a prisoner of war during the conflict. Their separation became permanent after the defeat of Aizu, and their divorce was finalized in December 1871. Her courageous actions and unconventional role in the war earned her the nickname "Bakumatsu Joan of Arc."

1.3. Life in Kyoto and Education

In 1871, Yae relocated to Kyoto, seeking out her brother, Yamamoto Kakuma, who had been imprisoned by the Satsuma Domain and was later released to serve as an advisor to the Kyoto prefectural government. Upon her arrival, Kakuma recommended her for a position as a substitute instructor at the Kyoto Women's School (京都女紅場Kyōto JokōbaJapanese), which later became Kyoto Prefectural Oki High School.

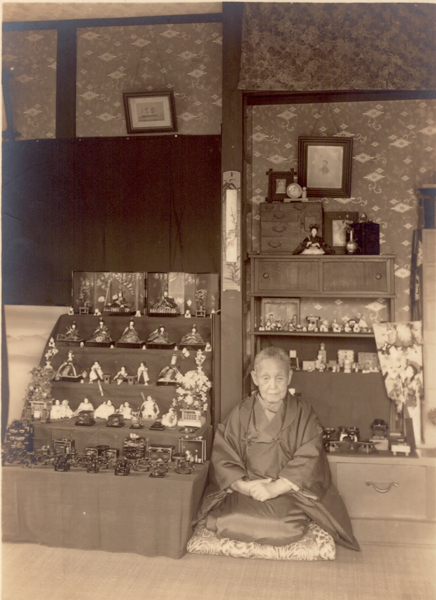

While working at the Kyoto Women's School, Yae cultivated an interest in traditional Japanese arts. She became acquainted with a sadō (Japanese tea ceremony) instructor from the prestigious Urasenke (裏千家Japanese) school. Through this connection, Yae immersed herself in the art of tea ceremony, eventually earning a tea-master qualification in 1894. She was granted the art-name Niijima Sōchiku (新島宗竹Niijima SōchikuJapanese) and later contributed to the spread of the Urasenke style by opening a tea ceremony classroom for women in Kyoto. She also developed an interest in kadō (Japanese flower arrangement), learning from the 42nd headmaster of the Ikenobō (池坊Japanese) school, Ikenobō Senjō. In 1896, she received a certificate acknowledging her proficiency in flower arrangement from Ikenobō.

During the early 1870s, Yae met Reverend Joseph Hardy Neesima (新島襄Niijima JōJapanese), an American Board missionary who frequently visited her brother Kakuma. Neesima, a former samurai, had spent a decade (1864-1874) studying in the United States. Upon his return to Japan in 1874, he embarked on establishing a Western-style school focused on promoting Christianity. However, his efforts faced strong opposition from Buddhists and Shintoists in Kyoto, who repeatedly petitioned the prefectural government to prevent its establishment.

1.4. Marriage to Niijima Jo and Doshisha

Yae and Neesima became engaged in October 1875. Shortly after their engagement, Yae was dismissed from her teaching position at the Kyoto Women's School due to governmental pressure stemming from the opposition to Neesima's Christian school. Despite this setback, Yae, alongside Neesima and her brother Kakuma, volunteered to help manage the newly founded Doshisha English School (同志社英学校Dōshisha EigakkōJapanese). She played an integral role in its establishment and subsequent growth.

Yae and Neesima married on January 3, 1876. Neesima, having been educated in the United States, was a strong advocate for women's rights. This progressive mindset influenced their marriage, which was notably different from conventional Japanese relationships of the time. In November 1876, with the assistance of American missionary Alice J. Starkweather, Yae established a small girls' school called Joshijuku (女学校JoshijukuJapanese) at the former residence of the Yanagihara family. This institution was later renamed Doshisha Branch School for Girls and then officially became Doshisha Girls' School (同志社女子大学Dōshisha Joshi DaigakuJapanese) in 1877.

While Neesima and Yae shared a loving and egalitarian relationship, their dynamic often contradicted the prevailing social norms of Edo period Japan. Neesima's courtesy towards Yae, such as allowing her to enter a carriage before him, was perceived by some as a sign of her being a "bad wife" (悪妻AkusaiJapanese), as it was interpreted as Yae dominating her husband. Despite such societal criticism, their bond remained strong. Neesima himself admired Yae's independent spirit, describing her lifestyle as "handsome" (ハンサムHansamuJapanese) in a letter to friends in the United States. He even wrote to Shozaburo Tokura (土倉庄三郎Japanese), a financial supporter of Doshisha and a leader of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement, expressing his concern for Yae's future and the school's welfare after his own inevitable passing due to heart disease. Joseph Hardy Neesima suddenly died on January 23, 1890, leaving Yae a widow.

1.5. Later Career and Nursing

Following Neesima's death, Yae's relationship with some of his disciples and colleagues at Doshisha School gradually became strained. She found it difficult to reconcile with students from the Satsuma Domain and Chōshū Domain, as these domains had attacked Aizu during the Boshin War. In her later career, Yae shifted her primary focus to nursing. On April 26, 1890, she became a regular member of the Japanese Red Cross Society.

During the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Yae volunteered as a nurse with the Japanese army and spent four months stationed at the Army Reserve Hospital in Hiroshima. She led a team of 40 nurses, providing care for wounded soldiers. A key aspect of her efforts during this time was advocating for the improvement of the social status of trained nurses. Her dedication and contributions were recognized by the Japanese government, and she was awarded her first Order of the Precious Crown (Seventh Class) in 1896, becoming the first woman outside of the Imperial House of Japan to be decorated for service to the country after the Meiji Restoration.

After the Sino-Japanese War, Yae continued her involvement in nursing by working as an instructor in nursing schools. When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, she once again volunteered, serving as a nurse at the Imperial Japanese Army hospital in Osaka for two months. For this service, she received her second Order of the Precious Crown (Sixth Class). Her compassionate care for all wounded soldiers, regardless of their nationality, including those from China and Russia, earned her widespread admiration from the media, which famously compared her to the renowned British nurse Florence Nightingale, giving her the nickname "Nightingale of Japan." In 1907, she donated the former residence of Joseph Neesima to Doshisha. For her lifelong commitment and service to the nation, she was further honored with a silver cup at the inauguration of the Shōwa Emperor in 1928.

Niijima Yae maintained her residence on Teramachi Street in Kyoto until her death. She passed away on June 14, 1932, at the age of 86. Her funeral was sponsored by Doshisha University and was attended by approximately 4,000 people. She was laid to rest at Doshisha Cemetery in Sakyō-ku, Kyoto, beside her husband Joseph Neesima. Her tombstone inscription was personally written by Tokutomi Sohō, a close friend and former student of Neesima.

2. Personal Life and Family

Niijima Yae did not have any biological children from either of her two marriages. However, she took in several adopted children throughout her life, though her relationships with them were not always smooth due to her strong personality.

After Joseph Neesima's death, the adopted son who succeeded the Niijima family, Koga, became estranged from Yae. Yae adopted three other children, mainly from the Yonezawa Domain, where she had temporarily resided after the Boshin War. In 1896, she adopted Sada, the daughter of Yamaguchi Gennosuke, a samurai from Yonezawa Domain, but their adoption was dissolved after two years. In 1900, she adopted Hatsuko (also known as Hatsune), the daughter of Amakasu Saburo, another samurai from Yonezawa, whose mother was Nakae, the daughter of Katsunori Teshiki (手代木勝任Japanese). Hatsuko married Hirotsu Tomonobu, who served as acting principal of Doshisha, in May 1901. They had four sons and two daughters. Tomonobu later became an English teacher at the Sixth High School in Okayama and then a professor and student supervisor at Yamagata High School before his retirement. He was later invited to become an executive at Sugamo Home School, where he served from 1927 to 1932. Yae maintained close contact with Hatsuko's family, often visiting them in Okayama and Sugamo. In her final years, Hatsuko's family cared for her during her illness. Yae had hoped for her talented adopted grandson, Niijima Joji (Hatsuko's son), to succeed her, but he passed away prematurely in June 1925 at the age of 23. In 1902, Yae also adopted Otsuka Koichiro, but this adoption lasted only three months before it was dissolved.

Despite the challenges in her adopted family relationships, Yae maintained a significant bond with Tokutomi Sohō (徳富蘇峰Japanese), a former student of Joseph Neesima, who was present at Neesima's deathbed. Sohō promised to treat Yae as Neesima's keepsake and kept his word, providing her with continuous support. Sohō, who became a member of the House of Peers in 1911, reportedly sent his entire annual salary from the Diet to Yae without opening the envelopes, supporting her financially until her death. Yae relied on Sohō in her later years, consulting him on various matters.

3. Assessment and Honors

Niijima Yae's life and achievements brought her significant recognition and awards, though her unconventional nature also subjected her to societal criticism.

3.1. Awards and Recognition

Yae received numerous official honors for her public service and contributions. Her earliest decoration, the Order of the Precious Crown, Seventh Class, was awarded in 1896 in recognition of her nursing service during the First Sino-Japanese War. For her continued efforts as a nurse during the Russo-Japanese War, she was awarded the Order of the Precious Crown, Sixth Class, in 1904. These honors were particularly significant as she was the first woman outside the Imperial House of Japan to be officially decorated for her service to the country after the Meiji Restoration. In 1928, she was further honored with a silver cup during the enthronement ceremony of the Shōwa Emperor, acknowledging her lifelong commitment to the nation.

Her courage and dedication in various fields earned her several distinguished epithets. She was widely known as the "Nightingale of Japan" due to her pioneering work in nursing and compassionate care for all soldiers. Her fierce fighting spirit and active participation in the Boshin War led to comparisons with the French heroine "Bakumatsu Joan of Arc" and the Japanese female warrior "Aizu Tomoe Gozen" (巴御前Tomoe GozenJapanese).

3.2. Societal Perception and Criticism

Despite her notable achievements, Yae often faced criticism and was a subject of intense scrutiny in Japanese society, particularly during her marriage to Joseph Neesima. Her independent spirit and unconventional behavior, which clashed with the traditional expectations of Japanese women in the Edo and early Meiji periods, led to her being labeled a "bad wife" (悪妻AkusaiJapanese). This label stemmed from her open and egalitarian relationship with Neesima, where he often showed her courtesy and respect in public, contrary to the custom where a wife was expected to be subservient to her husband. Observers, including some of Neesima's own students like Tokutomi Sohō (who later became a close confidant), viewed her assertive demeanor and Neesima's "lady-first" attitude as signs of her shrewishness.

Conversely, Neesima himself admired her strong, independent character. In a letter to his friends in the United States, he famously described her way of life as "handsome" (ハンサムHansamuJapanese). This term, when applied to Yae, became a distinctive part of her public image, leading to her being referred to as the "Original Handsome Woman" (元祖ハンサム・ウーマンGanso Hansamu WūmanJapanese). These conflicting perceptions highlight Yae's defiance of rigid societal norms and her pioneering role in embodying a different kind of womanhood in a rapidly changing Japan.

4. Legacy and Impact

Niijima Yae's enduring legacy is multifaceted, reflecting her contributions across various spheres of Japanese society. She is remembered as a powerful symbol of resilience and independence, especially for her extraordinary participation as a female warrior in the Boshin War, a role highly unusual for her era. Her later dedication to education was pivotal in the founding and development of Doshisha English School and, more directly, Doshisha Girls' School. Through this work, she provided crucial educational opportunities for women, challenging the limited scope of female education at the time.

Her most significant humanitarian impact came through her pioneering efforts in the nursing profession. By serving as an active nurse during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars and advocating for better social status for nurses, she played a crucial role in modernizing nursing in Japan and elevating its professional standing. Her compassionate approach, which extended equal care to all wounded soldiers, regardless of their nationality, earned her the enduring comparison to Florence Nightingale, cementing her reputation as a compassionate humanitarian.

Beyond her public service, Yae also left her mark on Japanese culture. Her mastery of the Urasenke tea ceremony, for which she earned the tea-master qualification and taught, and her proficiency in Ikenobō flower arrangement, contributed to the preservation and popularization of these traditional arts in Kyoto. Overall, Niijima Yae stands as a remarkable figure who consistently challenged conventional gender roles, contributing significantly to military, educational, medical, and cultural fields, and inspiring future generations with her unwavering spirit and commitment to social progress.

5. In Popular Culture

Niijima Yae remains a popular and frequently depicted historical figure in Japan, appearing in various forms of media that highlight her unique life and contributions.

- Novels:**

- Fukumoto Takehisa has written a series of novels about her, including Aizu Onna Senki (1978), Niijima Jō to Sono Tsuma (1978), and Handsome Woman, Saigo no Inori (2012).

- Mitsugu Saotome authored Meiji no Keimai (1990).

- Nakamura Akihiko included her in the short story Nokosu Tsuki Kage (1995).

- Hitomi Fujimoto wrote Bakumatsu Jūhime Den (2010), Ishin Jūhime Den (2012), and Niijima Yae Monogatari - Bakumatsu Ishin no Jūhime (2012).

- Ryō Hachiya published Tsukikage no Michi - Shōsetsu Niijima Yae (2012).

- Shun'ei Kunimatsu wrote Niijima Yae Aizu to Kyoto ni Saita Tairin no Hana (2012).

- Seiichirō Kusunoki authored Niijima Yae Ishin no Sakura (2012).

- The 2013 NHK Taiga drama Yae no Sakura was novelized by its original scriptwriter, Mutsumi Yamamoto, starting in 2012.

- Mami Shiraishi wrote Niijima Yae Gekido no Jidai o Massugu ni Ikita Josei no Monogatari (2012).

- Ayuna Fujisaki wrote Niijima Yae Monogatari - Sakura Mau Kaze no Yō ni (2013).

- Manga:**

- Shiori Matsuo created Kiyoraka ni Takaku ~Handsome Girl~ (2012) and Yae ~Aizu no Hana~ (2013).

- Mitsuru Fujii illustrated Handsome Lady - Niijima Yae Monogatari (2012).

- Korosuke Ezaki published Yaeko Ransho! (2012).

- She is featured in Learning Manga Sekai no Denki NEXT: Niijima Yae (2012) by Yutaka Hiiragi and Shūhei Mikami.

- The 2013 NHK Taiga drama Yae no Sakura also had several manga adaptations, including by Yōhei Takemura (2013), Shi Ritsuki (2013), and Yuzuru Kuki (2013).

- Teio Teio and Sakichi Aizu collaborated on Yamamoto-san Chi no Gun Girl (2016).

- She appeared in volume 6 of Kenji Sonishi's Nekoneko Nihonshi (2019).

- Television Dramas:**

- Yae was the main protagonist in the 1985 TV Asahi drama special Onna no Tatakai Aizu Soshite Kyoto (女のたたかい 会津そして京都Japanese), portrayed by Komaki Kurihara.

- She was also the central figure in the 2013 NHK Taiga drama Yae no Sakura (八重の桜Japanese), where she was portrayed by Haruka Ayase.

- Yae appeared in the 1986 Nippon Television drama Byakkotai (白虎隊Japanese), portrayed by Yoshiko Tanaka.

- She was also featured in the 2007 TV Asahi drama Byakkotai (白虎隊Japanese), portrayed by Noriko Nakagoshi.

- In a historical variety show, Nihonshi Suspense Gekijō (日本史サスペンス劇場Japanese) by Nippon Television (2009), she was portrayed by Miyuki Ōshima.

- Television Anime:**

- She appears in the 2019 E-Tele anime Nekoneko Nihonshi, voiced by Yū Kobayashi.

- Video Games:**

- Yae is a character in Tecmo Koei's 2013 game Toukiden.

- She is also featured in Sega Fave's 2024 game Eiketsu Taisen, voiced by Hitomi Ohwada.

- Stage Productions:**

- The reading play Kyo, Koko e ni Saku. (今日、ここのへに咲く。Japanese) was re-staged in 2019, featuring performances by Ai Takano and Reiko Tanaka.

- Local Characters:**

- Yaetan (八重たんJapanese) is a mascot character created by the Fukushima Prefectural Tourism and Exchange Division for the promotion of Yae no Sakura and continues to serve as a PR character for Fukushima Prefecture.

- Moe no Sakura (萌えの桜Japanese) features Yamamoto Yae (voiced by Ayane Sakura) as a character. This is a line of local moe character goods from Aizuwakamatsu City, with illustrations by Cherry Arai.

- Sakura Yae (さくら八重Japanese) is a "moe-sake" produced by Hanaharu Sake Brewery, also featuring illustrations by Cherry Arai.