1. Overview

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (nisefɔʁ njɛpsni-SEF-or NYEPSFrench; 7 March 1765 - 5 July 1833) was a pioneering French inventor best known for his groundbreaking contributions to the development of photography. He is widely recognized as the individual who succeeded in capturing the world's first permanent photographic images, laying the foundational groundwork for a technology that would profoundly reshape human communication, art, and scientific documentation. His work involved the invention of heliography, a technique he used to create the earliest surviving products of a photographic process, including what is considered the world's oldest surviving camera photograph, "View from the Window at Le Gras." Beyond photography, Niépce, alongside his elder brother Claude, also conceived and developed the Pyréolophore, one of the world's earliest internal combustion engines. Despite his profound innovations, Niépce faced significant financial struggles and died relatively unacknowledged for his pivotal role in photography, highlighting the often-arduous path and delayed recognition experienced by many pioneering inventors.

2. Biography

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce's life was marked by intellectual curiosity, persistent scientific inquiry, and the challenges inherent in pursuing groundbreaking inventions, often with limited resources and recognition during his lifetime.

2.1. Early life and education

Niépce was born Joseph Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône, Saône-et-Loire, France, on 7 March 1765. His family was affluent, with his father working as a wealthy lawyer. Joseph had an older brother, Claude (1763-1828), who would later become his key collaborator in scientific research and invention. He also had a sister and a younger brother named Bernard. The family, despite their wealth, experienced significant losses during the French Revolution.

Joseph adopted the name Nicéphore during his studies at the Oratorian college in Angers, in honor of Saint Nicephorus, the ninth-century Patriarch of Constantinople. At this college, he received a comprehensive education in science and the experimental method. He quickly distinguished himself academically, demonstrating considerable talent, and upon graduating, he continued to work as a professor at the college.

2.2. Military career

Following his academic period, Niépce entered military service. He served as a staff officer in the French Army under Napoleon Bonaparte, spending several years in Italy and on the island of Sardinia. However, his military career was cut short due to ill health, forcing him to resign in 1794.

After his resignation from the military, Niépce married Agnes Romero. He subsequently took on an administrative role in post-revolutionary France, serving as the Administrator of the district of Nice in 1795. However, he resigned from this administrative position the same year, reportedly due to unpopularity, to fully dedicate himself to scientific research alongside his brother Claude. In 1801, the brothers returned to their family's estates in Chalon-sur-Saône, where they were reunited with their mother, sister, and younger brother. They managed the family estate as independently wealthy gentlemen-farmers, engaging in agricultural pursuits such as raising beets and producing sugar.

2.3. Personal life and family

Niépce's personal life was intertwined with his scientific pursuits and family dynamics. He married Agnes Romero, and they had a son named Isidore (1805-1868).

His older brother, Claude Niépce, was a crucial collaborator in his research endeavors. However, Claude later descended into a state of delirium and severely mismanaged the family fortune, squandering much of it on ill-fated business ventures related to the Pyréolophore engine. In 1827, Nicéphore traveled to England to visit Claude, who was seriously ill and living in Kew. Claude's financial mismanagement had a significant negative impact on Nicéphore's own financial stability in his later years.

After Nicéphore's death, his son Isidore formed a partnership with Louis Daguerre to further develop photographic techniques. In 1839, Isidore was granted an annual government pension in exchange for publicly disclosing the technical details of his father's heliogravure process, acknowledging Niépce's foundational work.

Beyond his immediate family, Niépce had other notable relatives who also contributed to scientific fields. His cousin, Claude Félix Abel Niépce de Saint-Victor (1805-1870), was a chemist who made significant advancements in photography, being the first to use albumen in the photographic process. He also produced photographic engravings on steel and discovered in 1857-1861 that uranium salts emit an invisible form of radiation that fogs photographic plates. Photojournalist Janine Niépce (1921-2007) is a distant relative of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce.

2.4. Financial situation and death

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce died on 5 July 1833, at the age of 68, from a stroke. By the time of his death, he was financially ruined, largely due to his brother Claude's extensive squandering of the family's wealth. So dire was his financial state that his grave in the cemetery of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes had to be financed by the local municipality. This cemetery is located near the family house where he conducted many of his pioneering experiments and created some of the world's oldest surviving photographic images.

3. Scientific Research and Inventions

Niépce dedicated his life to scientific research, driven by a desire to innovate and solve practical problems. His endeavors spanned various fields, but his most revolutionary contributions were in the realm of photography and the development of early internal combustion engines.

3.1. Photography

Niépce's pursuit of photography stemmed from his interest in finding a new method of image reproduction, initially as an alternative to lithography, a printing technique for which he felt he lacked the necessary artistic skill. His acquaintance with the camera obscura, a popular drawing aid that projected beautiful but ephemeral "light paintings," inspired him to seek a way to permanently capture these images without manual tracing.

3.1.1. Early experiments and heliography

The precise date of Niépce's first photographic experiments remains uncertain. Around 1816, he began experimenting with capturing camera images on paper coated with silver chloride. While he achieved some success in capturing images, these early attempts produced negatives (where light areas appeared dark and vice versa), and he could not find a way to prevent them from darkening completely when exposed to light for viewing. This challenge prompted him to explore other light-sensitive substances.

Niépce eventually focused on Bitumen of Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt. He was particularly interested in its property of becoming less soluble in oil after exposure to light. This material had historically been used by artists as an acid-resistant coating for copper plates in etching.

His process, which he named heliography (meaning "sun drawing"), involved dissolving bitumen in lavender oil, a common solvent in varnishes, and thinly coating it onto a lithographic stone or a sheet of metal or glass. After the coating dried, a test subject-typically an engraving printed on paper-was placed in close contact over the surface. This assembly was then exposed to direct sunlight. After sufficient exposure, a solvent could be used to rinse away only the unhardened bitumen that had been shielded from light by the dark lines or areas of the test subject. The now-bare parts of the surface could then be etched with acid, or the remaining hardened bitumen could serve as the water-repellent material in lithographic printing.

In 1822, Niépce used this heliography process to create what is believed to be the world's first permanent photographic image: a contact print of an engraving of Pope Pius VII. However, this initial image was later destroyed when Niépce attempted to make prints from it.

3.1.2. Earliest photographic artifacts

The earliest surviving photographic artifacts created by Niépce date to 1825. These are copies of a 17th-century engraving depicting a man leading a horse and an image of a woman with a spinning wheel. These works are photo-etchings: ink-on-paper prints where the printing plates themselves were created photographically using Niépce's heliography process, rather than by traditional hand-engraving or drawing. One print of the "man with a horse" is preserved in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, while two examples of the "woman with the spinning wheel" are in a private collection in Westport, Connecticut. The 1825 "Man Leading a Horse" was sold for 443.00 K USD in 2002.

Niépce's correspondence with his brother Claude confirms that his first successful attempt at creating a permanent photograph of a real-world scene using a camera obscura occurred sometime between 1822 and 1827. The resulting image, titled "View from the Window at Le Gras," is now recognized as the oldest known camera photograph still in existence. This historic image had been considered lost for much of the 20th century until photography historians Helmut Gernsheim and Alison Gernsheim successfully tracked it down in 1952.

The exposure time required for "View from the Window at Le Gras" has been a subject of historical debate. Early estimates suggested eight or nine hours, based on the way sunlight illuminated buildings on opposite sides, implying an almost day-long exposure. However, later research, which recreated Niépce's processes using historically accurate materials, indicated that several days of exposure in the camera were actually needed to adequately capture such an image on a bitumen-coated plate.

3.1.3. Partnership with Louis Daguerre

In 1829, Niépce entered into a partnership with Louis Daguerre, a French artist and physicist who was also independently seeking a method for creating permanent photographic images with a camera. Together, they developed an improved photographic process called the physautotype, which utilized lavender oil distillate as its photosensitive substance.

This partnership lasted until Niépce's death in 1833. Following his passing, Daguerre continued to experiment, eventually developing his own distinct process, which he named the daguerreotype after himself. Although the daguerreotype only superficially resembled Niépce's original process, it became the first publicly announced photographic method. In 1839, Daguerre successfully persuaded the French government to purchase his invention and release it to the public. As part of this arrangement, the French government awarded Daguerre a yearly stipend of 6.00 K FRF for the rest of his life and granted Niépce's estate a yearly stipend of 4.00 K FRF. Niépce's son, Isidore, expressed dissatisfaction with this arrangement, arguing that Daguerre was receiving disproportionate credit and financial benefit from his father's foundational work. For many years, Niépce's significant contributions were indeed largely overlooked. However, later historians have brought his work back into prominence, and it is now widely acknowledged that his heliography was the first successful instance of what we now define as photography: the creation of a reasonably light-fast and permanent image through the action of light on a sensitive surface, followed by subsequent processing.

Despite being initially overshadowed by the excitement surrounding the daguerreotype, and being too insensitive for practical camera photography, the utility of Niépce's original bitumen process for its primary purpose as a printing method was eventually recognized. From the 1850s well into the 20th century, a thin coating of bitumen was extensively used as a slow but highly effective and economical photoresist for creating printing plates.

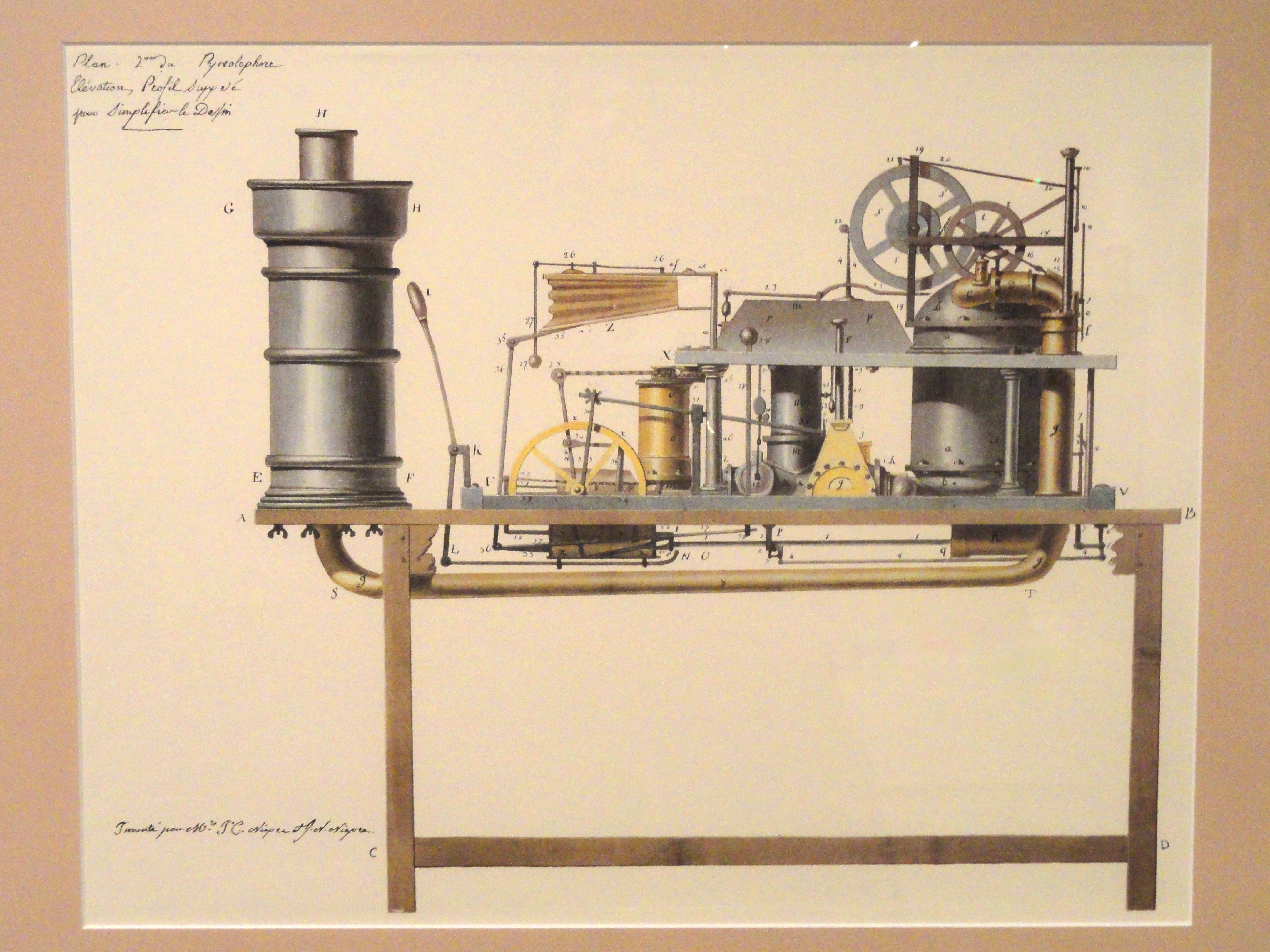

3.2. Pyréolophore

The Pyréolophore, one of the world's first operational internal combustion engines, was invented and patented by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and his brother Claude in 1807. This innovative engine operated on controlled dust explosions of lycopodium powder. The brothers successfully installed this engine on a boat, which then navigated against the current on the Saône. A decade later, the Niépce brothers further advanced their design by becoming the first in the world to develop an engine that incorporated a fuel injection system. On 20 July 1807, they received a patent for the Pyréolophore from Napoleon Bonaparte.

3.3. Other inventions

Niépce's inventive spirit extended beyond photography and internal combustion engines, encompassing other areas of mechanical and hydraulic engineering.

- Marly machine:** In 1807, the imperial French government initiated a competition for a new hydraulic machine to replace the original Marly machine, which supplied water from the Seine river to the Palace of Versailles. The original machine, constructed in Bougival in 1684, was tasked with pumping water a distance of 0.6 mile (1 km) and raising it 492 ft (150 m). The Niépce brothers devised a new hydrostatic principle for the machine and introduced further improvements in 1809. Their design incorporated more precise pistons, significantly reducing resistance. Extensive testing demonstrated its effectiveness: with a stream drop of 4.33 ft, their improved machine could lift water 11 ft. However, their progress was too slow; by December 1809, the Emperor had already decided to commission Jacques-Constantin Périer to build a steam engine for the Marly pumps instead.

- Vélocipède:** Niépce's curiosity also led him to the early precursor of the bicycle. In 1818, he became interested in the Laufmaschine (running machine) invented by Karl von Drais in 1817. Niépce built his own version, which he named the vélocipède (meaning "fast foot"), and it created quite a sensation on the local country roads. He further improved his machine by adding an adjustable saddle. This improved vélocipède is now exhibited at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce. In his correspondence, Niépce even contemplated the possibility of motorizing his machine, foreshadowing future developments in personal transportation.

4. Legacy and Commemoration

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce's innovative work, though not fully recognized during his lifetime, has left an indelible mark on history, particularly in the field of photography. His foundational contributions continue to be honored and studied.

4.1. Recognition and influence

Niépce's profound impact on the development of photography has gained increasing recognition over time. The lunar crater Niépce is named in his honor, acknowledging his pioneering spirit on a celestial scale.

His historic "View from the Window at Le Gras" heliograph is on permanent display at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. This artifact was rediscovered by photography historians Helmut and Alison Gernsheim in 1952 and subsequently acquired by the Humanities Research Center (later renamed the Harry Ransom Center) in 1963, ensuring its preservation and public accessibility. It is important to note that many of his original photographic works, including a significant number of his early pictures, were reportedly lost during World War II and the Battle of France, with only a few surviving.

Since 1955, the Niépce Prize has been awarded annually in France to a professional photographer who has lived and worked in the country for over three years. This prestigious award, introduced by Albert Plécy of the l'Association Gens d'Images, serves as a lasting tribute to Niépce's groundbreaking achievements and his enduring influence on the art and science of photography. Niépce's legacy lies in his unwavering dedication to capturing light and images, a pursuit that irrevocably changed human perception and documentation, making him a true visionary in the history of technology.