1. Overview

Narasaki Ryō, widely known as お龍OryōJapanese, was a significant figure during Japan's tumultuous Bakumatsu and Meiji periods, primarily recognized as the wife of Sakamoto Ryōma, a pivotal architect of the Meiji Restoration. Born into a physician's family in Kyoto, her life was marked by early financial hardship and resilience. Her quick thinking famously saved Ryōma's life during the 1866 Teradaya Incident, after which they embarked on what is widely considered Japan's first honeymoon. Following Ryōma's assassination, Ryō endured a challenging period of wandering and poverty, later remarrying the merchant Nishimura Matsubē and adopting the name 西村ツルNishimura TsuruJapanese. Despite Ryōma's posthumous fame, she faced increasing isolation and hardship in her later years, grappling with alcoholism and eventually dying in poverty. Her life story reflects the profound personal struggles and resilience of individuals caught within grand historical transformations, emphasizing her agency in a male-dominated era and the often-overlooked adversities faced by women of the period.

2. Life

The life of Narasaki Ryō was characterized by periods of prosperity and profound hardship, marked by her impactful relationship with Sakamoto Ryōma and the challenges she faced in its aftermath. This section details her journey from her birth and early experiences to her pivotal role in historical events and her subsequent struggles following Ryōma's death.

2.1. Birth and Early Life

Narasaki Ryō was born on July 23, 1841 (Tenpō 12, 6th day of the 6th month, by the lunisolar calendar) in Kyoto, near Tominokoji Rokkaku. She was the eldest daughter of Narasaki Shōsaku, a physician who served as the personal doctor to Prince Kuni Asahiko of Shōren-in-no-miya, and his wife, Shigeno Sada (also known as Natsu). She had two younger sisters, Mitsue (later Nakazawa Mitsue) and Kimi (later Sugeno Kimi), and two younger brothers, Taichirō and Kenkichi. The Narasaki family had ancestral roots as samurai in Chōshū Domain, but her great-grandfather's generation lost their samurai status due to a lord's displeasure, becoming rōnin.

Ryō grew up in a relatively affluent household, characteristic of her father's position. She was trained in traditional arts such as Ikebana (flower arrangement), Kōdō (incense ceremony), and Chanoyu (tea ceremony), though it is noted that she was not adept at cooking. Her family's fortunes dramatically reversed when her father, a loyalist, was arrested during the Ansei Purge. Although he was later pardoned, he fell ill and died in 1862 (Bunkyū 2) when Ryō was 21. His death plunged the family into severe financial hardship, forcing them to sell their furniture and clothing for survival.

During this desperate time, Ryō demonstrated remarkable bravery and resolve. When her mother was allegedly tricked, and her sisters Kimi and Mitsue were on the verge of being sold into forced labor-Kimi as a geisha to Shimabara and Mitsue as a jorō (prostitute) in Ōsaka-Ryō took decisive action. She sold her own kimonos to gather funds and traveled to Ōsaka, confronting two men with a knife. Her fierce determination, reportedly declaring, "Kill me, kill me! I came all the way to Ōsaka to be killed. This is interesting, kill me!" (as recounted in a letter from Sakamoto Ryōma on September 9, 1865), led her to successfully reclaim her sister. Ryōma later described her as a "truly interesting woman" in the same letter to his elder sister, Sakamoto Otome, detailing Ryō's difficult circumstances and resilience.

2.2. Meeting Sakamoto Ryōma

Following her father's death and the family's descent into poverty, Narasaki Ryō began working at the "Ōgiwa" inn in Shichijō Shinchi, Kyoto. Simultaneously, her mother, Sada, found employment as a cook at a hideout near the Daibutsu-den of Hōkō-ji, a sanctuary for Tosa Domain loyalist activists, including remnants of the Tenchūgumi. It was around 1864 (Genji 1) that Ryō first encountered Sakamoto Ryōma. She later recounted that upon their initial meeting, when Ryōma asked for her name and she wrote it down, he laughed, finding it amusing that their names shared a common character.

Ryōma became deeply smitten with Ryō and approached her mother, Sada, to propose marriage, which Sada accepted. Their relationship deepened amidst the turbulent political climate. In June 1864, during the Ikeda-ya Incident, the family's belongings were confiscated during what was known as the Daibutsu Incident. Ryōma himself described their living situation to his elder sister, Sakamoto Otome, in a letter dated September 9, 1865 (Keiō 1), stating, "We lived day to day, barely eating, truly a pitiable existence." Despite these hardships, he admired Ryō's strength, describing her as a "truly interesting woman." Ryō later recalled that she and Ryōma held an informal wedding ceremony on August 1, 1864.

2.3. Teradaya Incident and Honeymoon

Narasaki Ryō is most famously known for her pivotal role in saving Sakamoto Ryōma's life during an assassination attempt at the Teradaya Incident on March 9, 1866 (Keiō 2, 1st month, 23rd day by the lunisolar calendar). Before this, Ryōma had entrusted her to Otose, the proprietress of the Teradaya Inn in Fushimi, where Ryō worked under the alias "Oharu" as Otose's adopted daughter. During this period, Ryō recounted various encounters, including narrowly avoiding the Shinsengumi with Ryōma and an incident where Kirino Toshiaki allegedly attacked her in her bed. There were even rumors that Kondō Isami, the commander of the Shinsengumi, was enamored with Ryō and would buy her combs and hairpins.

On the evening of the incident, just one day after the successful formation of the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance brokered by Ryōma, he was staying at the Teradaya Inn with his bodyguard, Miyoshi Shinzo. While Ryō was taking a bath, she became acutely aware of numerous constables outside. Demonstrating incredible presence of mind, she swiftly grabbed a spear thrust through the bathroom window, confronted the would-be assassin with a loud voice, and immediately leaped out of the bathtub. Donning only a robe, she ran out into the garden and up to the second floor, urgently warning Ryōma and Miyoshi Shinzo. Her quick actions prevented a surprise attack, allowing Ryōma and Miyoshi to fight their way out, albeit sustaining injuries. Ryō further assisted their escape by moving heavy stone pickle tubs that were blocking the back gate, creating a clear path for them.

Ryōma later described the harrowing event in detail in a letter to his elder brother, Sakamoto Gonpei, dated December 4, 1866 (Keiō 2), where he proudly introduced her as "my wife, Ryō." To his sister Otome, he expressed profound gratitude, writing, "Because of this woman Ryō, Ryōma's life was saved."

Ryōma's injuries, particularly to his fingers, prompted Saigō Takamori to recommend a trip to the hot springs of Satsuma Province for healing. On March 4, 1866, Ryōma and Ryō departed Ōsaka aboard the Satsuma Domain ship "Mikuni-maru." During the voyage, Ryōma spoke of his dream to sail around Japan in a steamship once peace was established. Ryō famously retorted, "I don't need a house. A ship is enough. I want to travel even to foreign countries," to which Ryōma chuckled, calling her an "eccentric woman." Saigō, upon hearing this anecdote later, heartily agreed, remarking, "Because she's eccentric, your life was saved."

The couple arrived in Kagoshima on March 10. Accompanied by Satsuma samurai Yoshii Tomozane, they visited various hot springs, including Hinatayama Onsen and Shiomizu Onsen. Their journey was not merely for recovery; they enjoyed sightseeing at Inukai Falls, hunting birds with pistols in the mountains, and even, remarkably, pulling out the legendary Ama-no-Sakakoko spear from the peak of Takachiho-no-mine, much to the dismay of their escort, Tanaka Kichibei. Ryōma meticulously documented this trip in his letter to Otome, complete with illustrations, and Ryō herself later recounted her memories of the journey. This trip was first described as a "honeymoon" by Sakazaki Shiran in his work "Kanketsu Senri驹," which introduced Ryōma to the public, and it is now widely recognized as Japan's first modern honeymoon, though some historical accounts suggest Komatsu Tatewaki's trip may have predated it.

2.4. Life After Ryōma's Death

Following the assassination of Sakamoto Ryōma, Narasaki Ryō faced a dramatically altered life, marked by hardship, wanderings, a second marriage, and eventual decline.

2.4.1. Early Wanderings and Support

Narasaki Ryō was widowed after Sakamoto Ryōma's assassination during the Ōmiya Incident in Kyoto on December 10, 1867 (Keiō 3, 11th month, 15th day). The news reached her in Shimonoseki on December 2, where she was staying. Though she had prepared for such an eventuality, she reportedly cut her hair and wept profusely upon hearing the news. Ryōma and Ryō had no children. Following his death, Miyoshi Shinzo, who had been with Ryōma during the Teradaya Incident, took responsibility for Ryō's welfare. In accordance with Ryōma's wishes, Ryō's younger sister, Kimi, married Kannō Kakubē (also known as Chiyatori no suke), a member of the Kaientai.

In March 1868 (Keiō 4), Ryō was sent to the Sakamoto family in Tosa Province as Ryōma's widow. However, her stay there was brief, lasting only about three months. While some accounts suggest discord with Ryōma's elder sister, Sakamoto Otome, Ryō herself later stated that Otome had been kind to her. Instead, Ryō's strained relationship was primarily with her brother-in-law, Gonpei, and his wife. In her later recollections, Ryō expressed resentment, accusing them of ill-treatment and driving her away due to their covetousness for the reward money promised to Ryōma.

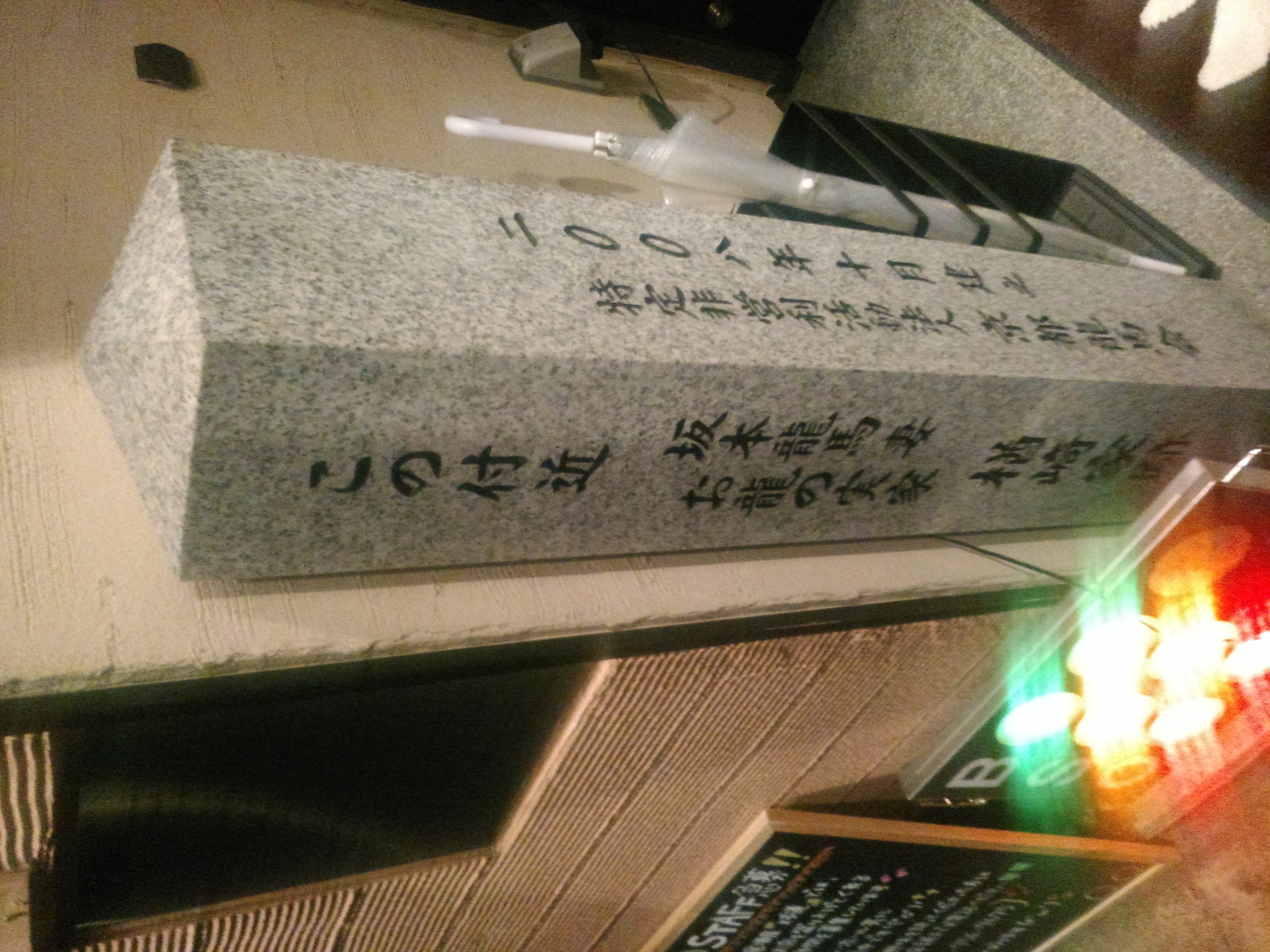

Ryō then sought refuge with the Chigaya family, Kannō Kakubē's biological family, in Washiki Village, Aki County (present-day Geisei Village, Kōchi Prefecture). Her stay was again cut short when Kakubē left for the United States to serve in the Imperial Japanese Navy, making it impossible for her to remain with the Chigaya family. Around mid-1869 (Meiji 2), she departed Tosa. Before leaving, Ryō made a poignant request: that all of Ryōma's letters to her, which she considered deeply personal and not for others to see, be burned. Consequently, only one of Ryōma's letters addressed to her survives today. Geisei Village later erected bronze statues of Ryō and her sister Kimi to commemorate her temporary residence there.

After leaving Tosa, Ryō went to Kyoto, relying on Otose of the Teradaya Inn once more. She initially lived in a small hermitage near Ryōma's grave, serving as his grave guardian. However, finding it difficult to remain in Kyoto, she relocated to Tokyo. There, she sought assistance from prominent figures who had been close to Ryōma, such as Katsu Kaishū and Saigō Takamori. Saigō, sympathetic to her plight, provided her with 20 JPY. He promised further support upon his return from political engagements, but this never materialized as he soon resigned due to his defeat in the Seikanron debate. Ryō subsequently received some aid from former Satsuma samurai Yoshii Tomozane and former Kaientai member Hashimoto Kyūdayu.

Despite Ryōma's growing posthumous fame and the success of many former Kaientai members in the new Meiji government, very few offered Ryō consistent support. Sakamoto Nao, who inherited Ryōma's family headship, reportedly gave her a cold reception. The general reputation of Ryō among former Kaientai members was poor. Tanaka Mitsuaki, a former Rikuentai member who rose to become Minister of the Imperial Household, recalled that even her brother-in-law, Kannō Kakubē, refused to assist her during a meeting of the Zuizan-kai (a society honoring loyalists like Takechi Hanpeita), stating that her "behavior was bad, and she would not listen to advice, so it was impossible to care for her." Ryō herself later lamented that only Saigō, Katsu, and Otose had shown her genuine kindness.

2.4.2. Remarriage and Later Years

In 1874 (Meiji 7), Ryō found work as a maid at the Tanaka-ya restaurant in Kanagawa-juku, reportedly introduced by either Katsu Kaishū or Kannō Kakubē. Accounts from Tanaka-ya suggested she was stubborn and difficult to work with, though the veracity of these claims is debated.

The following year, in 1875 (Meiji 8), Narasaki Ryō remarried to a merchant named Nishimura Matsubē, taking on the new name of Nishimura Tsuru (西村ツルNishimura TsuruJapanese), and settled in Yokosuka. According to testimonies from Yasuka Hideho and Nakajō Nakako (Kakubē's niece), Nishimura Matsubē was originally the young master of a kimono wholesale business who had known Ryō during her time at the Teradaya Inn. His family business declined during the chaos of the Restoration, leading him to move to Yokosuka and become a street vendor. He frequented Kakubē's house, which facilitated his marriage to Ryō, arranged either by Kakubē or Otose. Another account suggests they met at Tanaka-ya.

After her marriage to Matsubē, Ryō took in her aging mother, Sada. She also adopted her sister Mitsue's son, Matsunosuke, born on August 15, 1874 (Meiji 7), as their heir. However, tragedy struck again in 1891 (Meiji 24), when both her mother Sada and adopted son Matsunosuke died in quick succession.

Ryōma's fame, which had faded into obscurity, was reignited in 1883 (Meiji 16) with the publication of Sakazaki Shiran's novel "Kanketsu Senri驹" in the Tōyō Shimbun. This work, despite containing many historical inaccuracies and fictional elements, became a bestseller. Ryō herself expressed regret over its "many errors." As a result, researchers like Yasuka Hideho and Kawata Yukiyama sought her out to record her reminiscences. Yasuka's works, including "Hangonkō," "Zoku Hangonkō," and "Ishin no Zanmu," were published in magazines from 1899 to 1900, while Kawata's "Senri駒 Kojitsudan" and "Senri駒 Kojitsudan Shūi" appeared in the Tōyō Shimbun in 1899. In "Senri驹 Kojitsudan," Ryō famously remarked at the end, "If Ryōma had lived, there would have been more interesting things..."

By 1897 (Meiji 30), when Yasuka Hideho visited her, Ryō was living in a small, impoverished row house in Yokosuka. In her later years, she developed alcoholism, reportedly often telling Matsubē while intoxicated, "I am Ryōma's wife." Her life grew even more desolate when her sister, Mitsue, who had become dependent on Ryō after her husband's death, developed an intimate relationship with Matsubē, leading them to leave Ryō and live separately. Ryō then came under the care of Kudō Sotaro, a retired military officer. In 1904 (Meiji 37), just before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Ryōma's fame surged once more due to a widespread story that Empress Shōken had a dream about him, bringing Ryō back into public attention.

2.5. Death

In January 1906 (Meiji 39), as Narasaki Ryō lay critically ill, she received a telegram of sympathy from Empress Dowager Kōgō Taifu Kagawa Keizō (a former Rikuentai member), and General Inoue Yoshika began collecting donations for her care. On January 15, 1906, Ryō died at the age of 64 (by Western count, 66 by traditional Japanese counting).

She was buried at Shigaraki-ji temple in Ōtsu, Yokosuka. For many years, a proper tombstone could not be erected due to lack of funds. However, eight years after her death, in August 1914 (Taishō 3), with the financial assistance of Tanaka Mitsuaki and Kagawa Keizō, and her sister Nakazawa Mitsue acting as the principal sponsor, a tomb was finally established. Notably, the tombstone bears the inscription "Gave Shōshii, Wife of Sakamoto Ryōma, Ryūko's Grave," rather than mentioning her second husband, Matsubē. Nishimura Matsubē himself died six months later at the age of 70. A portion of Ryō's ashes was also interred at Kyoto Ryōzen Gokoku Shrine, where Ryōma is buried. On January 15, 2010, a joint memorial service for Ryōma and Ryō was held at Shigaraki-ji, 143 years after Ryōma's death.

3. Posthumous Evaluation and Legacy

Narasaki Ryō's life, particularly her challenging later years, has been subject to historical re-evaluation, especially given her connection to the now-revered Sakamoto Ryōma. Yamamoto Naoe, the proprietress of the Komatsu restaurant, who knew Ryō, provided a poignant posthumous assessment. She recalled Ryō as a woman about ten years her senior, who had fallen on hard times and lived in poverty in Yokosuka before her death at the age of 64 (or 68 by traditional Japanese count) during the Russo-Japanese War. Yamamoto noted that despite her impoverished circumstances, Ryō retained a dignified character and refined appearance.

Yamamoto emphasized the historical context: at the time of Ryō's later life, Sakamoto Ryōma himself was largely forgotten by the public. She lamented that a woman of such beauty and education, despite receiving numerous offers for remarriage, eventually chose to remain true to Ryōma's memory, even after her second marriage to Matsubē. Yamamoto stated that Ryō lived with Nishimura Bunpei (Matsubē) for several years but ultimately separated, unable to fully move past Ryōma. She described Ryō's later life as one of aiding female hairdressers and seeking solace in alcohol, a testament to her wounded spirit. Yamamoto concluded, "She was a person who served the country, and her half-life was pitiable," highlighting the tragic trajectory of a woman whose significant contributions were largely unrecognized and whose personal struggles deepened even as her first husband's fame would later soar. This perspective underscores the often-overlooked personal cost borne by individuals, particularly women, amidst grand historical changes, emphasizing her resilience and the systemic neglect she faced.

4. Controversy Regarding Oryō's Photos

For many years, the only authenticated photograph of Narasaki Ryō has been one taken in her later years, published on December 15, 1904 (Meiji 37), in the Tokyo Niroku Shimbun. This photograph was taken by Yasuka Hideho, who had previously promised its publication in the magazine "Bunko" in 1900, stating then that it was the "first time" Oryō had ever been photographed. If Yasuka's assertion was accurate, it implied that no photographs of Ryō in her youth existed.

However, a controversy arose in 1979 when a standing photograph of a woman, discovered in an album belonging to the Omiya Iguchi Shinsuke family (formerly part of Nakai Hiro's collection), was publicly presented as a possible image of a younger Oryō. Furthermore, a seated photograph of a woman, published in "Sepia-iro no Shōzō Bakumatsu Meiji Meishi Shashin Korekushon" (2000), was also widely believed to be Oryō. These two newly discovered photographs appeared to depict the same individual and were confirmed to have been taken at the Uchida Kuichi photography studio in Asakusa Ōji-chi.

Despite the initial excitement, many experts expressed skepticism regarding the authenticity of these new photographs. In 2008, the Kōchi Prefectural Sakamoto Ryōma Memorial Museum commissioned the National Research Institute of Police Science (NRIPS) to compare the seated photograph with the authenticated late-life photograph using superimposition techniques. The NRIPS concluded that there was a "possibility of being the same person," noting "no morphological differences to judge as separate individuals" and "effective morphological similarities."

However, this appraisal method was criticized as flawed by researchers like Takahashi Shinichi, a former associate professor at Keio University, who pointed out that the NRIPS's approach was identical to an earlier analysis conducted by Kamatani Naoki of the Sony Sakamoto Ryōma Research Group in 1996, which had also reached a similar conclusion of "same person." Critics argued that such superimposition techniques, while showing similarities, did not definitively prove identity, especially when manipulated to align facial features.

Consequently, while the seated photograph was widely circulated as "young Oryō," it was later largely concluded not to be her, due to persistent doubts about the reliability of the NRIPS's comparative method, as highlighted by Morishige Kazuo in "Rekishitsū" (2011). A theory suggesting the woman in the disputed photographs was Era Kayo, a mistress of Kido Takayoshi or Itō Hirobumi, was also disproven.

The debate largely settled in 2013, when Hirayama Susumu of the Japan Military Uniform Research Society discovered another visiting card photograph at an old bookstore in Tokyo. This photograph depicted the same woman as the previously unverified "young Oryō" photos, striking an identical pose, differing only in the position of one hand. This discovery provided strong evidence that the woman was not Narasaki Ryō, as it suggested a common studio pose rather than a unique portrait of Ryō. Furthermore, another image of this same woman was found within a collage of visiting card photographs, bearing the inscription "Doi Okugata" (Mrs. Doi), indicating she was later a concubine of the Viscount Doi family. Multiple other photographs of this same woman have since been found, solidifying the consensus that the disputed photos do not depict Narasaki Ryō.

5. Oryō in Popular Culture

Narasaki Ryō, often known as Oryō, has become a recurring figure in Japanese popular culture, frequently portrayed in various media due to her association with Sakamoto Ryōma and her dramatic role in the Teradaya Incident. Her character embodies resilience and strength, often serving as a romantic interest or a symbol of the ordinary individual caught in extraordinary times.

She has appeared in numerous **films**, including:

- Kaientai (1939), played by Haruyo Ichikawa

- Ishin no Kyoku (1942), played by Haruyo Ichikawa

- Bakumatsu (1970), played by Sayuri Yoshinaga

- Bakumatsu Seishun Graffiti Ronin Sakamoto Ryoma (1986), played by Mieko Harada

- Ryoma wo Kitta Otoko (1987), played by Ryoko Kuninaka

- Golf Yoake Mae (1987), played by Keiko Takahashi

- Ryoma's Wife, Her Husband and Her Lover (2002), played by Kyoka Suzuki

Her presence is also significant in **television dramas**, particularly in the popular NHK taiga drama series:

- Ryoma ga Yuku (1965, MBS), played by Hiroko Yamada

- Ryōma ga Yuku (1968, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Ruriko Asaoka

- Katsu Kaishū (1974, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Akira Kawaguchi

- Kashin (1977, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Sumi Shimamoto

- Hakage no Tsuyu (1979, Asahi Broadcasting Corporation), played by Keiko Kishō

- Ryoma ga Yuku (1982, TV Tokyo), played by Naoko Otani

- Bakumatsu Seishun Graffiti Sakamoto Ryoma (1982, NTV), played by Masako Natsume

- Kage no Gundan Bakumatsu-hen (1985, Kansai Telecasting Corporation), played by Yūko Asano

- Sakamoto Ryōma (1989, TBS), played by Yūko Natori

- Tobu ga Gotoku (1990, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Yōko Higuchi

- Ryoma ga Yuku (1997, TBS), played by Yasuko Sawaguchi

- Ryoma ga Yuku (2004, TV Tokyo), played by Rina Uchiyama

- Shinsengumi! (2004, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Kumiko Aso

- Atsuhime (2008, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Mikako Ichikawa

- Ryōmaden (2010, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Yōko Maki

- JIN - Jin - Kanketsu-hen (2011, TBS), played by Machiko Washio

- Jidaigeki Hotei Special: Hikokunin wa Sakamoto Ryoma (2015, Jidaigeki Senmon Channel), played by Rei Okamoto

- FNS27 Hour TV Nihon no Rekishi (2017, Fuji TV), played by Ayame Goriki

- Saigōdon (2018, NHK Taiga Drama), played by Asami Mizukawa

Beyond dramas, she has been featured in other **television programs**:

- Rekishi Hiwa Historia: Ryoma ga Aishita Onna ~Oryō Shiraresaru Sugao~ (2013, NHK General TV), played by Tomoko Nawata

- Furutachi Talking History ~Bakumatsu Saidai no Nazo Sakamoto Ryoma Ansatsu, Kanzen Jikkyō~ (2019, TV Asahi), played by Manami Hashimoto

Oryō's story has also been adapted for the **stage**:

- Otoyo - Ane, Otome kara Sakamoto Ryoma e no Dengon (1990, Mokutōsha performance, written and directed by Kunio Shimizu), which received the Minister of Education Award for Arts and the Teatro Theatre Award.

Her character extends into **animated media** and **video games**:

- Nekoneko Nihonshi (2016, ETV)

- Ryō - RYO- (2013)

- Like a Dragon: Ishin! (2015, Sega), voiced by Nanao Sakuraba

- Like a Dragon: Ishin! Kiwami (2023, Sega), voiced by Manami Sugihei

Additionally, Oryō is a notable figure in **manga** and **novels**:

- Ōi! Ryōma (1986-1996, Shogakukan, original story by Tetsuya Takeda, art by Yu Koyama)

- Samurai Sensei (2013-2020, Libre Publishing, by S. K. Kuroe)

- Oryō (2008, Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha, by Sanjūri Uematsu)

- Gekkin o Hiku Onna Oryō ga Yuku (2010, Gentosha, by Iichirō Kagawago)

- Yuke, Oryō (2016, Bungeishunjū, by Yoshinobu Kadoi)

- Sana to Ryō (2017, Ohta Publishing, by U Teraji)