1. Overview

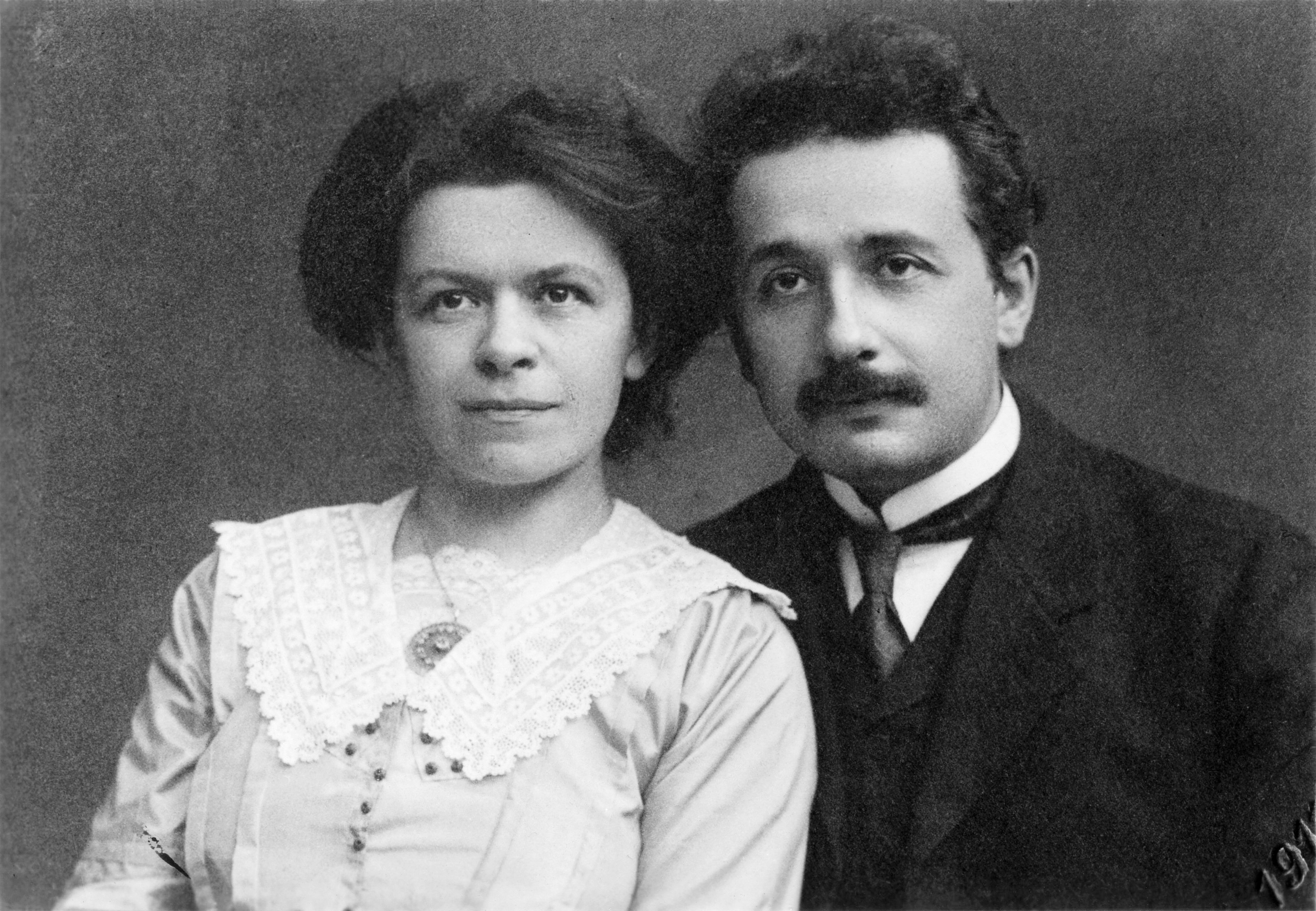

Mileva Marić was a Serbian physicist and mathematician, best known as the first wife of Albert Einstein. Born in Titel, Austria-Hungary (modern Serbia) in 1875, Marić displayed exceptional intellectual aptitude from a young age, particularly in mathematics and physics. She pursued higher education in a field heavily dominated by men, studying at the University of Zurich and later at the Zurich Polytechnic (now ETH Zurich), where she met and developed a close relationship with Einstein.

Their marriage in 1903 led to the birth of three children: Lieserl Einstein (whose fate remains uncertain), Hans Albert Einstein, and Eduard Einstein. A significant historical debate surrounds Marić's potential contributions to Einstein's early scientific work, including his groundbreaking 1905 "Annus Mirabilis papersAnnus Mirabilis papersGerman". While many historians argue she made no significant scientific contributions, others suggest she was a supportive scientific companion and may have collaborated with him, especially in their early years. After a strained marriage, Marić and Einstein separated in 1914 and divorced in 1919.

Following her divorce, Marić faced considerable personal and financial challenges, notably managing the severe schizophrenia of her son Eduard, which required extensive care and led to her selling properties to cover expenses. She died in Zurich in 1948 at the age of 72. Posthumously, Marić has received various honors and has been depicted in numerous cultural works, highlighting her complex legacy as a pioneering woman in science and a figure whose historical narrative is intertwined with one of the most famous scientists of all time.

2. Early Life and Education

Mileva Marić was born on December 19, 1875, in Titel, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, which is now part of Serbia. She was the eldest of three children born to Miloš Marić (1846-1922) and Marija Ružić-Marić (1847-1935). Her family was affluent, and shortly after her birth, her father concluded his military career to take up judicial positions, first in Ruma and later in Zagreb.

Marić began her secondary education in 1886 at a girls' high school in Novi Sad but transferred the following year to the Sremska Mitrovica Gymnasium in Sremska Mitrovica. From 1890, she attended The Royal Serbian Grammar School in Šabac. In 1891, her father secured special permission for her to enroll as a private student at the all-male Royal Classical High School in Zagreb. She successfully passed the entrance examination and entered the tenth grade in 1892. Her academic aptitude was evident, and in February 1894, she received special permission to attend physics lectures. She completed her final exams in September 1894, achieving "very good" grades in both mathematics and physics, just one grade below the highest possible "excellent".

That same year, Marić became seriously ill and decided to move to Switzerland. On November 14, she began attending the "Girls High School" in Zurich. In 1896, she passed her Matura examination, a prerequisite for university admission, and subsequently studied medicine at the University of Zurich for one semester.

3. Studies at ETH Zurich and Meeting Albert Einstein

In the autumn of 1896, Marić transferred to the Zurich Polytechnic (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, ETH), having successfully passed the mathematics entrance examination with an average grade of 4.25 on a scale of 1 to 6. She enrolled in the diploma course designed to train secondary school teachers in physics and mathematics (section VIA). Notably, she was the only woman in her group of six students and only the fifth woman to ever enter that section of the Polytechnic. It was during this period that she met Albert Einstein, who was enrolled in the same program, and they quickly became close friends.

In October 1897, Marić traveled to Heidelberg to study at Heidelberg University for the winter semester of 1897/98, where she attended physics and mathematics lectures as an auditor. She returned to the Zurich Polytechnic in April 1898. Her curriculum at ETH Zurich was extensive, encompassing subjects such as differential and integral calculus, descriptive and projective geometry, mechanics, theoretical physics, applied physics, experimental physics, and astronomy.

Marić took her intermediate diploma examinations in 1899, one year later than the other students in her group. Her average grade was 5.05 on a scale of 1 to 6, placing her fifth out of the six students who took the examinations that year. Her grade in physics was 5.5, which was the same as Einstein's. However, in 1900, she failed her final teaching diploma examinations, achieving an average grade of 4.00 and notably scoring only 2.5 in the mathematics component, specifically the theory of functions. Einstein, in contrast, passed the examination with an average grade of 4.91, placing fourth among the candidates.

Marić's academic pursuits were further interrupted in May 1901 when she became pregnant by Einstein during a short holiday in Italy. Three months into her pregnancy, she resat the diploma examination but failed for a second time, without improving her grades. Consequently, she discontinued work on her diploma dissertation, which she had intended to develop into a PhD thesis under the supervision of physics professor Heinrich Friedrich Weber.

4. Marriage and Family Life

Marić's academic career was significantly altered by her pregnancy with Einstein's child in 1901. To avoid scandal, she traveled to her hometown in Novi Sad, where their daughter was born in January 1902. The girl was referred to as "Hansel" in their correspondence before her birth and later as Lieserl Einstein. The fate of Lieserl remains uncertain, with some sources suggesting she died in late summer 1903, possibly from scarlet fever which left her with permanent damage, while others indicate she was given up for adoption in Serbia.

In 1903, Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein married in Bern, Switzerland, where Einstein had secured a position at the Federal Office for Intellectual Property. Their first son, Hans Albert Einstein, was born in 1904. The family moved several times in the following years due to Einstein's changing academic appointments. They resided in Bern until 1909, after which they moved to Zurich. In 1910, their second son, Eduard Einstein, was born. The family relocated to Prague in 1911 when Einstein accepted a teaching position at Charles University. A year later, in 1912, they returned to Zurich as Einstein was offered a professorship at his alma mater, the Zurich Polytechnic.

In July 1913, Marić expressed distress over her husband's impending relocation to Berlin. In August, the family planned a walking holiday with their sons, joined by Marie Curie and her two daughters. Marić was temporarily delayed due to Eduard's illness but later joined the group. In September 1913, the Einsteins visited Marić's parents near Novi Sad, where Marić had her sons baptized as Eastern Orthodox Christians on the day they were to depart for Vienna. After Vienna, Marić returned to Zurich, while Einstein visited relatives in Germany. Before Christmas, she traveled to Berlin to stay with Fritz Haber, who assisted her in finding accommodation for the family's move in April 1914. The couple left Zurich for Berlin in late March. On their way, Marić took a swimming holiday with the children in Locarno, arriving in Berlin in mid-April.

5. Separation and Divorce

The marriage between Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein had been under strain since 1912. This period coincided with Einstein's renewed contact and regular correspondence with his cousin, Elsa Löwenthal. Marić, who had never wished to move to Berlin, grew increasingly unhappy in the city. In mid-July 1914, shortly after settling in Berlin, Einstein presented Marić with harsh conditions if she were to remain with him. Although she initially accepted these terms, she soon reconsidered. On July 29, 1914, the day after World War I began, Marić left Germany with her sons and returned to Zurich, marking a permanent separation.

Following their separation, Einstein made a legal commitment to provide Marić with an annual maintenance of 5.60 K Reichsmark in quarterly installments, which amounted to just under half of his salary at the time. He largely adhered to this commitment. After the required five years of separation, the couple officially divorced on February 14, 1919.

As part of their divorce settlement, they negotiated terms regarding the Nobel Prize money that Einstein anticipated he would soon receive. It was agreed that the prize money would be placed in trust for their two sons. Marić would receive the interest from this fund but would not have authority over the principal capital without Einstein's permission. In 1922, after Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, Marić received the promised money. Based on newly released letters, it was reported that Marić eventually invested the Nobel Prize money in three apartment buildings in Zurich to generate income. She resided in one of these properties, a five-story house at Huttenstrasse 62, while the other two served as investments.

6. Debate over Collaboration with Einstein

The extent to which Mileva Marić contributed to Albert Einstein's early scientific work, particularly the groundbreaking Annus Mirabilis papers of 1905, remains a subject of considerable historical debate. While many historians of physics generally conclude that she made no significant scientific contribution to these works, other scholars propose that she served as a supportive scientific companion, potentially assisting him materially in his research, or even that they developed scientific concepts together during their student years.

6.2. Debate over collaboration

The debate surrounding Marić's collaboration with Einstein also draws heavily from their personal letters.

John Stachel argues that instances where Einstein referred to "our" theory or "our" work in letters were primarily written during their student days, at least four years before the 1905 papers were published. Stachel suggests that these references might pertain to their diploma dissertations, for which they had both chosen the same topic: experimental studies of heat conduction. He further notes that Einstein typically used "our" in general statements, but consistently used "I" and "my" when detailing specific ideas he was developing. For example, letters to Marić show Einstein referring to "his" studies and "his" work on the electrodynamics of moving bodies over a dozen times, compared to only one reference to "our" work on the problem of relative motion.

Stachel also points out that in Marić's surviving letters that directly responded to Einstein's accounts of his latest ideas, she provided no scientific feedback. Her letters, unlike Einstein's, largely contained personal matters or comments related to her Polytechnic coursework. Stachel concludes that there are "no published papers, no letters with a serious scientific content, either to Einstein nor to anyone else; nor any objective evidence of her supposed creative talents." He adds that there are no even hearsay accounts of her conversations with others that contain specific scientific content or claim to report her ideas.

Thus, while some scholars argue there is insufficient evidence to support the idea of Marić directly helping Einstein develop his theories, others contend that their letters suggest a collaborative relationship, at least until 1901, before their children were born.

Further arguments in the collaboration debate are based on their interactions:

- Marić's brother and other relatives provided eyewitness accounts of Marić and Albert discussing physics together during their marriage.

- The couple's first son, Hans Albert (born 1904), stated that his mother gave up her scientific ambitions after marrying Einstein in 1903. However, he also recalled that his parents' "scientific collaboration continued into their marriage" and that he remembered seeing them "work together in the evenings at the same table." This suggests a complex and perhaps evolving dynamic in their intellectual relationship.

It is also noted that Einstein continued to produce highly significant scientific work and gain international renown long after his separation from Marić in 1914, and after their divorce, while Marić did not publish any independent scientific results after failing her ETH diploma exams.

7. Later Life and Personal Difficulties

After her divorce from Albert Einstein in 1919, Mileva Marić faced significant personal and financial challenges. In 1922, she received the Nobel Prize money that Einstein was awarded, as stipulated in their divorce agreement. This money, approximately 180.00 K CHF, was to be held in trust for their two sons, with Marić having the right to draw on the interest, but not the principal, without Einstein's permission.

Marić invested the Nobel Prize money in three apartment buildings in Zurich to generate income. She lived in one of these properties, a five-story house located at Huttenstrasse 62, while the other two were managed as investments.

A major source of difficulty in Marić's later life was the severe health issues of her son, Eduard. Around 1930, at approximately 20 years old, Eduard experienced a breakdown and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. By the late 1930s, the escalating costs of his care at the University of Zurich's psychiatric clinic, "Burghölzli", became overwhelming for Marić. To cover these expenses, she was compelled to sell the two investment houses. In 1939, to prevent the loss of the Huttenstrasse house where she resided, Marić agreed to transfer its ownership to Einstein, while retaining power of attorney over it. Einstein continued to provide regular financial contributions for the care and maintenance of Eduard and Marić herself, even after his emigration to the United States with his second wife, Elsa.

8. Death

Mileva Marić suffered a severe stroke and died at the age of 72 on August 4, 1948, in Zurich, Switzerland. She was interred at the Nordheim-Cemetery in Zurich. Her son, Eduard Einstein, remained institutionalized until his own death in 1965.

9. Legacy and Honors

Mileva Marić has received posthumous recognition for her significance as a woman in science and her complex historical narrative.

In 2005, Marić was honored in Zurich by ETH Zurich and the Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster. A memorial plaque was unveiled at her former residence in Zurich, the house at Huttenstrasse 62, in her memory. In the same year, a bust of Marić was placed in Sremska Mitrovica, the town where she attended high school. Another bust is located on the campus of the University of Novi Sad. A high school in her birthplace of Titel is named after her. Sixty years after her death, in June 2009, a memorial plate was placed on the house of the former clinic in Zurich where she died, and a memorial gravestone was dedicated to her at the Nordheim-Cemetery in Zurich, where she is buried.

Marić's life and the debate surrounding her contributions have inspired various cultural depictions:

- In 1995, Narodna knjigaSerbian in Belgrade published the book Mileva Marić AjnštajnSerbian by Dragana Bukumirović, a journalist with Politika.

- In 1998, Vida Ognjenović produced a drama titled Mileva AjnštajnSerbian, which was translated into English in 2002. Ognjenović later adapted this play into a libretto for the opera MilevaSerbian, composed by Aleksandra Vrebalov, which premiered in 2011 at the Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad.

- In her 2016 novel The Other Einstein, Marie Benedict offers a fictionalized account of the relationship between Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein.

- In 2017, Marić's life was depicted in the first season of the television series Genius, which focused on Einstein's life. She was portrayed by Nikki Hahn, Samantha Colley, and Sally Dexter at different stages of her life.

- A fictionalized depiction of Mileva Marić (portrayed by Christina Jastrzembska) and her potential contributions to Einstein's work appeared in the first episode of the second season of the time-traveling superhero television series, DC's Legends of Tomorrow.

- In 2019, physicist and writer Gabriella Greison applied for a posthumous degree for Mileva Marić at ETH Zurich. After four months of discussion, the university denied the request.

- Mileva Marić is a major character in Margaret Peterson Haddix's 2012 young-adult science-fiction novel Caught, part of "The Missing" series.

- In the 2022 novel Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, Mileva Marić is mentioned twice as an example of a pioneering woman scientist whose work was subsumed under that of her famous scientist husband.