1. Overview

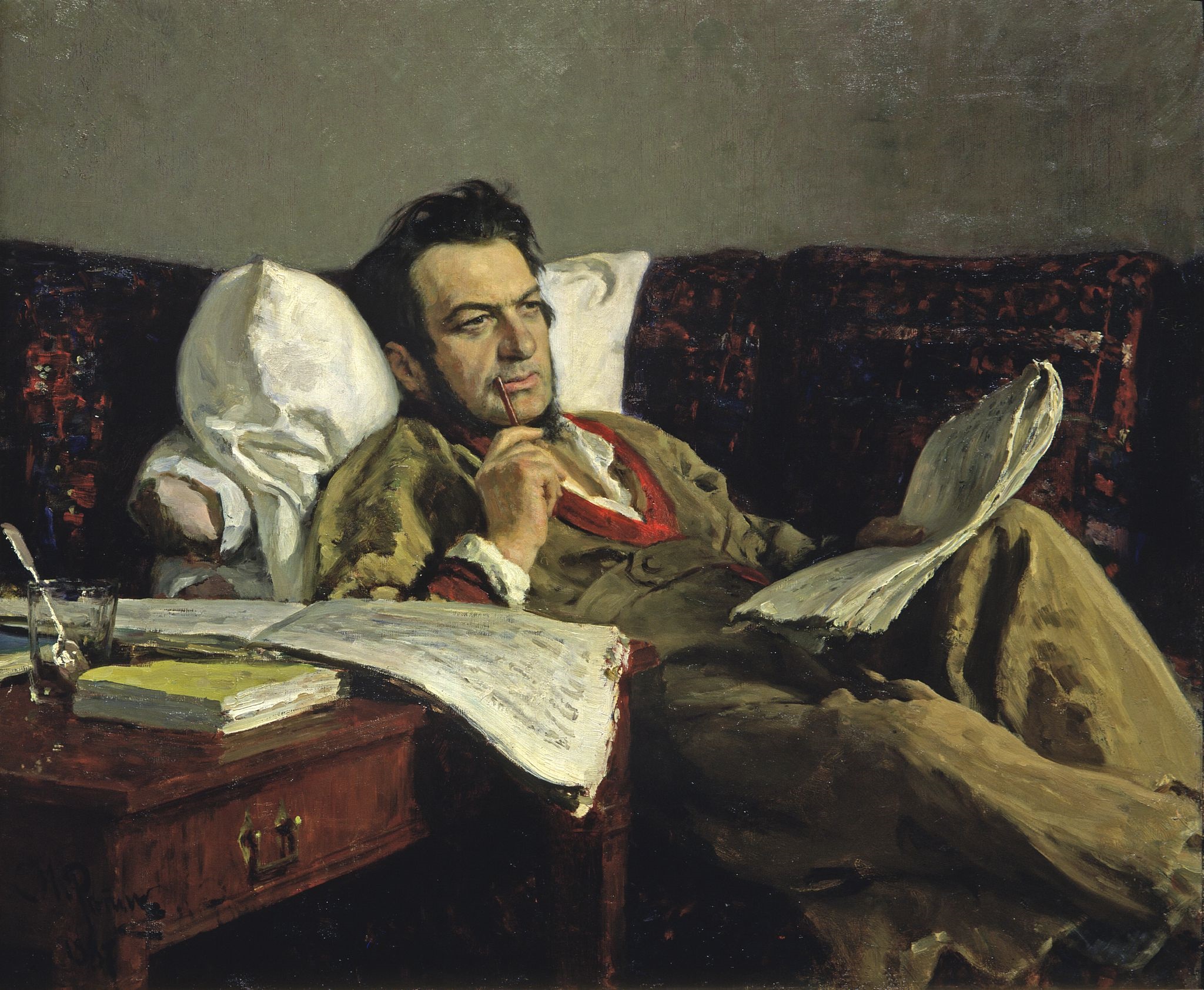

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (Михаил Иванович Глинкаmʲɪxɐˈil ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkəRussian) was the first Russian composer to achieve widespread recognition within his own country, and he is widely regarded as the foundational figure of Russian classical music. His compositions profoundly influenced subsequent Russian composers, particularly the members of The Five, who further developed a distinct Russian musical style. Glinka's work was instrumental in establishing a unique Russian artistic identity that holds a prominent place in world culture, and he is often called the "father of modern Russian music."

2. Early Life and Education

Mikhail Glinka's early life was shaped by his noble upbringing and exposure to diverse musical influences, which laid the groundwork for his groundbreaking compositions. His formal education in Saint Petersburg further broadened his academic and musical horizons.

2.1. Early Life and Family Background

Glinka was born on June 1, 1804 (May 20, 1804 Old Style), in the village of Novospasskoye, located near the Desna River in the Smolensk Governorate of the Russian Empire, now part of the Yelninsky District of the Smolensk Oblast. His wealthy father was a retired army captain, and the family had a strong tradition of loyalty and service to the tsars. Several members of his extended family possessed lively cultural interests, fostering an environment where music was appreciated. Glinka's great-great-grandfather, Wiktoryn Władysław Glinka, was a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth nobleman of the Trzaska coat of arms, who received lands in the Smolensk Voivodeship. In 1655, Wiktoryn converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, taking the new name Yakov Yakovlevich, and retained ownership of his lands under the tsar. His family's coat of arms was originally granted after his conversion from Lithuanian paganism to Catholicism, following the Union of Horodło.

Mikhail was raised by his paternal grandmother, who was overly protective and pampering, often feeding him sweets, wrapping him in furs, and confining him to her room, which was kept at 77 °F (25 °C). This upbringing contributed to him becoming somewhat of a hypochondriac later in life, often relying on numerous physicians and falling victim to quackery.

2.2. Musical Awakening and Early Education

During his youthful confinement, the only music Glinka heard was the sounds of the village church bells and the folk songs sung by passing peasant choirs. The church bells were tuned to a dissonant chord, accustoming his ears to strident harmony. While his nurse occasionally sang folk songs, the peasant choirs, who utilized the podgolosochnaya technique (an improvised style involving dissonant harmonies below the melody), significantly influenced his departure from the smooth progressions of Western harmony.

After his grandmother's death, Glinka moved to his maternal uncle's estate, located approximately 6.2 mile (10 km) away. There, he was exposed to his uncle's orchestra, which performed works by composers such as Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven. At around ten years old, he heard them play a clarinet quartet by the Finnish composer Bernhard Henrik Crusell, an experience that profoundly affected him. Years later, he recalled this moment, writing, "Music is my soul." While his governess taught him Russian, German, French, and geography, he also received initial instruction on the piano and violin.

2.3. Education in Saint Petersburg

At the age of 13, Glinka moved to the capital, Saint Petersburg, to attend a school for children of the nobility. During his six years there, he expanded his academic knowledge by studying Latin, English, Persian, mathematics, and zoology, and significantly broadened his musical experience. He received three piano lessons from John Field, the Irish composer known for his nocturnes, who spent time in Saint Petersburg. Glinka then continued his piano lessons with Charles Mayer and began to compose.

Upon leaving school, his father wished for him to join the Foreign Office, and Glinka was appointed assistant secretary of the Department of Public Highways in 1824. This light workload allowed him to embrace the life of a musical dilettante, frequently attending the city's drawing rooms and social gatherings. He composed a considerable amount of music during this period, including melancholy romances that entertained wealthy amateurs. His songs from this era are considered among the most interesting parts of his early work.

3. European Travels and Influence

Glinka's extensive travels across Europe were pivotal in his artistic development, allowing him to study with renowned musicians and absorb Western musical traditions, which profoundly shaped his compositional aspirations.

3.1. Italian Sojourn

In 1830, acting on a physician's recommendation, Glinka embarked on a journey to Italy with tenor Николай Кузьмич ИвановNikolai Kuzmich IvanovRussian. They traveled leisurely through Germany and Switzerland before settling in Milan. There, Glinka took lessons at the conservatory with Francesco Basili. He found the study of counterpoint particularly irksome. After three years of immersing himself in Italian operatic culture, listening to singers, composing romances, and meeting influential figures like Felix Mendelssohn and Hector Berlioz, he grew disenchanted with Italy. This period solidified his conviction that his life's mission was to return to Russia and compose in a distinctly Russian style, aiming to achieve for Russian music what Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini had accomplished for Italian music.

3.2. German Studies

His return journey took him through the Alps, and he briefly stopped in Vienna, where he heard the music of Franz Liszt. He then spent another five months in Berlin, where he undertook serious composition studies under the distinguished teacher Siegfried Dehn. This period was highly productive, yielding important works such as a Capriccio on Russian Themes for piano duet and an unfinished Symphony on Two Russian Themes, which further refined his musical craft and theoretical knowledge.

3.3. Encounters with European Composers

During his European travels, Glinka met and interacted with several influential composers. Beyond Mendelssohn and Berlioz in Italy, he also encountered Liszt in Vienna. Later, in 1844, he spent nine months in France, where he deepened his friendship with Hector Berlioz, who conducted excerpts from Glinka's operas and wrote an appreciative article about his work. Glinka, in turn, admired Berlioz's music and resolved to compose some fantasies pittoresques for orchestra. These interactions fostered his international musical perspective and enriched his understanding of diverse compositional approaches.

4. Career and Major Works

Glinka's professional career was marked by the creation of two seminal operas and significant orchestral, instrumental, and vocal compositions, which collectively laid the foundation for a unique Russian musical tradition.

4.1. Operas

Glinka's two major operas, A Life for the Tsar and Ruslan and Lyudmila, are considered cornerstones of Russian opera, establishing its patriotic and fantastical themes and incorporating folk elements.

4.1.1. A Life for the Tsar (Ivan Susanin)

A Life for the Tsar was the first of Glinka's two great operas. It was originally titled Ivan Susanin. Set in 1612, the opera tells the story of the Russian peasant and patriotic hero Ivan Susanin, who sacrifices his life for the Tsar by deliberately misleading a group of marauding Poles who were hunting the Tsar. Tsar Nicholas I himself followed the work's progress with keen interest and suggested the change in the title to A Life for the Tsar. The opera premiered with great success on December 9, 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos, who had previously composed an opera on the same subject in Italy. The Tsar rewarded Glinka for his work with a ring valued at 4.00 K RUB. During the Soviet era, the opera was frequently staged under its original title, Ivan Susanin, due to its patriotic themes centering on a national hero rather than the Tsar.

4.1.2. Ruslan and Lyudmila

Glinka soon embarked on his second opera, Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Alexander Pushkin, was hastily conceived in approximately 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was reportedly intoxicated at the time. Consequently, the opera is often considered a dramatic muddle. However, the quality of Glinka's music in Ruslan and Lyudmila is generally regarded as even higher than in A Life for the Tsar. The overture is particularly notable for featuring a descending whole tone scale associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor, who abducts Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev. While the opera includes much Italianate coloratura and several routine ballet numbers in Act 3, Glinka's significant achievement lies in his innovative use of folk melody, which is thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material, especially in the exotic scenes, is oriental in origin. When it debuted on December 9, 1842, it was received coolly, but it subsequently gained popularity and is now recognized for its imaginative scope and musical innovations.

4.2. Orchestral and Instrumental Works

Glinka's contributions to orchestral and instrumental music showcase his mastery of diverse genres and his pioneering use of folk material.

4.2.1. Symphonic Poems and Overtures

Among Glinka's key orchestral works are his symphonic poems and overtures, which demonstrate his command of orchestral color and his ability to integrate folk material. The symphonic poem Kamarinskaya (1848), based on Russian folk songs, is particularly significant, as it is considered the first orchestral piece to effectively utilize Russian national material. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky famously remarked that Kamarinskaya was "the acorn from which the oak" of later Russian symphonic music grew. Glinka also composed two notable Spanish-inspired orchestral works: Jota Aragonesa (1845), also known as Capriccio brillante on the Jota Aragonesa or Spanish Overture No. 1, and A Night in Madrid (1848, revised 1851), or Memories of a Summer Night in Madrid (Spanish Overture No. 2). Other orchestral works include overtures in D major and G minor (1822-26), Andante Cantabile and Rondo (1826), an unfinished Symphony on Two Russian Themes (1834), Polonaise on a Spanish Bolero Theme in F major (1855), and Valse-Fantaisie in B minor (1856).

4.2.2. Piano and Chamber Music

Glinka's contributions to piano and chamber music are also noteworthy. His significant piano pieces include numerous variations on themes by other composers (such as Mozart, Cherubini, Bellini, Donizetti, Alyabyev) and on Russian folk songs. He also composed mazurkas, nocturnes, waltzes, polkas, and other character pieces like "A Farewell to Saint Petersburg" (1840), a collection of 12 songs including "The Lark," which was later arranged for solo piano by Mily Balakirev. For chamber ensembles, his works include a Septet in E-flat major (1823), two string quartets (D major, 1824; F major, 1830), a Viola Sonata in D minor (1825-28), the Trio Pathétique in D minor for piano, clarinet, and bassoon (1832), and a Grand Sextet in E-flat major (1832). The Trio Pathétique is particularly praised for its blend of Italianate lyricism and Slavic melancholy.

4.3. Vocal Music

Glinka composed approximately 80 art songs, known as romances, and various choral works. His romances are celebrated for their lyrical and expressive qualities, contributing significantly to the Russian song tradition. Notable examples include "Do Not Tempt Me Needlessly" (1825), "Venetian Night" (1832), "Say Not That Love Will Pass" (1834), "I Am Here, Inezilla" (1834), "The Night Review" (1836), "Doubt" (1838), "The Fire of Longing Burns in My Heart" (1838), "The Night Zephir" (1838), "Sing Not, O Nightingale" (1838), and "I Recall a Wonderful Moment" (1840). These songs often feature poetic texts and showcase Glinka's melodic gift. He also composed vocal ensembles and choral pieces, including the "Glory" chorus from A Life for the Tsar.

4.4. Role at the Imperial Chapel Choir

In 1837, Glinka was appointed as the conductor of the Imperial Chapel Choir, a prestigious position that provided him with a yearly salary of 25.00 K RUB and lodging at the court. His tenure lasted until 1839. In 1838, at the suggestion of the Tsar, he traveled to Ukraine to recruit new voices for the choir. The 19 new boys he found earned him an additional 1.50 K RUB from the Tsar. This role provided him with financial stability and further immersed him in the Russian musical establishment.

5. Musical Style and Innovation

Glinka's musical language was revolutionary for its time, characterized by a unique synthesis of Russian folk elements and Western classical techniques, which ultimately defined a distinct Russian national style.

5.1. Fusion of Folk and Western Traditions

Glinka skillfully blended Russian folk melodies, rhythms, and harmonic practices with Western classical compositional techniques, creating a novel synthesis that became the hallmark of his style. He was deeply impressed by the beauty of Russian peasant songs and the unique improvised dissonant harmonies (podgolosochnaya) used in their choirs from his childhood. While his operas, particularly A Life for the Tsar, incorporated traditional Italianate structures, Glinka infused them with Russian folk material, making it an integral part of the musical argument rather than mere ornamentation. His later works, like Kamarinskaya, further demonstrated his confidence in treating ethnic material, absorbing folk music not only from Russia but also from other countries he visited, such as Spain. This fusion marked a significant departure from the prevailing Western-dominated musical landscape in Russia.

5.2. Development of Russian National Style

Glinka played a foundational role in establishing a national musical identity for Russia. Before him, musical culture in Russia was largely imported from Europe, with little specifically Russian music gaining prominence. Glinka's operas, especially A Life for the Tsar, were the first to present historical events realistically within a Russian context, marking the emergence of a truly Russian musical voice. This new direction was first recognized by Alexander Serov, and later championed by Vladimir Stasov, who became the theorist of this cultural trend. Glinka's distinct national style was subsequently developed further by composers of "The Five" (also known as "The Mighty Handful").

According to modern Russian music critic Viktor Korshikov, Russian musical culture would not have developed without three key operas: Glinka's Ivan Susanin (where the main character is the people) and Ruslan and Lyudmila (a mythical, deeply Russian intrigue), and Dargomyzhsky's The Stone Guest. Glinka's work, and the composers and creative individuals he inspired, were instrumental in shaping a distinctly Russian artistic style that holds a prominent place in world culture.

6. Personal Life

Glinka's personal life, though sometimes challenging, influenced his creative output. In 1835, he married Maria Petrovna Ivanova. While his initial fondness for her is said to have inspired the trio in the first act of his opera A Life for the Tsar, the marriage was short-lived and ultimately unhappy. Maria was reportedly tactless and uninterested in his music, and Glinka's naturally sweet disposition was said to have coarsened under constant criticism from his wife and mother-in-law. The marriage ended in divorce in May 1841. After the divorce, he moved in with his mother, and later with his sister, Lyudmila Shestakova. In his later years, particularly during his travels in Spain, he met Don Pedro Fernández, who became his secretary and companion for the last nine years of his life. Glinka was a great traveler, fluent in several languages, and his extensive journeys abroad were partly due to the higher regard his music received outside Russia compared to conservative circles within his homeland.

7. Death and Burial

After a period of living quietly in Paris from 1852 to 1854, Glinka moved to Berlin to continue his studies in music theory. He died suddenly in Berlin on February 15, 1857 (February 3, 1857 Old Style), following a cold and suffering from a liver ailment. He was initially buried in Berlin. However, a few months later, his body was exhumed and transported to Saint Petersburg, where it was reinterred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery. This reinterment reflected his national significance and the desire to honor him in his homeland.

8. Legacy and Commemoration

Glinka's lasting impact on Russian and world music is profound, and he continues to be remembered and honored through various tributes and recognitions.

8.1. Influence on Russian Composers

Glinka's work had a profound influence on subsequent generations of Russian composers, most notably "The Five" (also known as "The Mighty Handful"), including Mily Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. These composers embraced Glinka's pioneering integration of Russian folk elements and his vision for a distinct national musical style. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky famously stated that Glinka's orchestral composition Kamarinskaya (1848) was "the acorn from which the oak" of later Russian symphonic music grew, underscoring its foundational importance. Glinka's guidance and example were crucial in the development of Russian nationalism in music.

8.2. Commemorative Tributes

Numerous institutions and awards have been named in Glinka's honor, demonstrating his enduring legacy. In 1884, Mitrofan Belyayev founded the annual Glinka Prize, whose early winners included prominent composers such as Alexander Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, César Cui, and Anatoly Lyadov. Three Russian conservatories bear his name: the Nizhny Novgorod State Conservatory, the Novosibirsk State Conservatory, and the Magnitogorsk State Conservatory. Beyond Earth, Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Chernykh named a minor planet, 2205 Glinka, in his honor after its discovery in 1973. A crater on Mercury is also named after him.

8.3. Cultural Impact and Popular Culture

Glinka's music has maintained its presence in popular culture. His "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya" (Patriotic Song), supposedly written for a national anthem contest in 1833, gained significant attention in the late 20th century. In 1990, the Supreme Soviet of Russia adopted it as the regional anthem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it was unofficially retained and then officially confirmed as the Russian national anthem in 1993, serving in this capacity until 2000 when it was replaced by the Soviet anthem with new lyrics. The stirring overture to Glinka's opera Ruslan and Lyudmila is widely recognized as the theme music for the long-running U.S. television comedy series Mom. The creators of the series felt that the fast-paced, complex orchestral music effectively reflected the characters' struggles to overcome destructive habits and cope with the demands of daily life.

8.4. Controversies and Criticisms

Despite his significant contributions, Glinka has been associated with certain controversies. Glinkastraße in Berlin was named in his honor. However, in the wake of the George Floyd protests in 2020, there was a proposal to rename the adjacent Mohrenstraße U-Bahn station to "Glinkastraße." This plan was ultimately canceled due to Glinka's reputed antisemitism, leading to public debate. Additionally, in September 2022, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a street in Dnipro, Ukraine, that had been named after Glinka, was renamed to honor Queen Elizabeth II.

9. Works Overview

Mikhail Glinka's compositional output spans operas, orchestral works, piano and chamber music, and vocal music, showcasing his versatility and innovative spirit.

9.1. Operas

- A Life for the Tsar (originally Ivan Susanin) (1836, in 5 acts)

- Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842, in 5 acts)

9.2. Orchestral Works

- Overture in D major (1822-26)

- Overture in G minor (1822-26)

- Andante Cantabile and Rondo (1826)

- Symphony on Two Russian Themes in D minor (1834, unfinished)

- Spanish Overture No. 1: Capriccio brillante on the Jota Aragonesa in E-flat major (1845)

- Fantasy Kamarinskaya in D major (1848)

- Spanish Overture No. 2: A Night in Madrid (Memories of a Summer Night in Madrid) in A major (1851)

- Polonaise on a Spanish Bolero Theme in F major (1855)

- Valse-Fantaisie in B minor (1856)

9.3. Piano and Chamber Music

- Piano Solo:**

- Variations on a Theme from Mozart's The Magic Flute in E-flat major (1822)

- Variations on an Original Theme in F major (1824)

- Variations on the Russian Folk Song Along the Gentle Valley in A minor (1826)

- Variations on a Theme from Cherubini's Faniska in B-flat major (1826)

- Variations on the Romance Bless My Mother in E major (1826)

- Five New Contredanses (1826?)

- Four Contredanses (1828)

- Cotillion in B-flat major (1828)

- Mazurka in G major (1828)

- Nocturne in E-flat major (1828)

- Brilliant Rondo on a Theme from Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi in B-flat major (1831)

- Variations on a Theme from Donizetti's Anna Bolena in A major (1831)

- Variations on Two Themes from the Ballet Kia-King in D major (1831)

- Farewell Waltz in G major (1831)

- Variations on Alyabyev's Romance The Nightingale in E minor (1833)

- Mazurka in A-flat major (1833-34)

- Mazurka in F major (1833-34)

- Three Fugues (1833-34)

- Patrioticheskaya Pesnya (Motif of a National Anthem) in C major (1834-36)

- Variations on a Theme from Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi in C major (1835)

- Mazurka in F major (1835)

- Waltz in B-flat major (1838)

- Waltz in E-flat major (1838)

- Galop in E-flat major (1838-39)

- Contredanse in D major The Nun (1839)

- Grand Waltz in G major (1839)

- Fantasy Waltz in B minor (1839)

- Nocturne in F minor Farewell (1839)

- Polonaise in E major (1839)

- Five Contredanses (1839)

- Bolero in D minor (1840)

- Mazurka in C minor (1843)

- Tarantella on a Russian Folk Song in A minor (1843)

- A Greeting to the Homeland (1847, 4 pieces): No. 1 "Memory of a Mazurka" in B-flat major, No. 2 "Barcarole" in G major, No. 3 "Prayer" in A major, No. 4 "Variations on a Scottish Folk Song" in F major (based on The Last Rose of Summer)

- Polka in D minor (1849)

- Mazurka in C major (1852)

- Children's Polka in B-flat major (1854)

- Las Morales in G major (1855?)

- Mazurka in A minor (undated)

- Legeramente in E major (undated)

- Piano Duet:**

- Sword Dance (Cavalry Trot) in C major (1829-30)

- Sword Dance (Cavalry Trot) in G major (1829-30)

- Impromptu Galop on a Theme from Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore in B-flat major (1832)

- Capriccio on Russian Themes in A major (1834)

- Polka in B-flat major (1840)

- Chamber Music:**

- Septet in E-flat major (1823)

- String Quartet in D major (1824)

- Viola Sonata in D minor (1825-28)

- String Quartet in F major (1830)

- Trio Pathétique in D minor (1832) for clarinet, bassoon, and piano

- Grand Sextet in E-flat major (1832)

- Brilliant Divertimento on Bellini's La sonnambula in A-flat major (1832)

- Serenade on Donizetti's Anna Bolena in E-flat major (1832)

9.4. Vocal Music

- My Harp (1824)

- Do Not Tempt Me Needlessly (Elegy) (1825)

- Consolation (1826)

- The Poor Singer (1826)

- Ah, My Sweet, Thou Art a Beautiful Maiden (1826)

- Heart's Memory (1827)

- I love was your assurance (1827)

- Bitter, Bitter It Is for Me (Maiden's Sorrow / Russian Song) (1827)

- Tell Me Why (1827 or 1828)

- Just One Instant (1827 or 1828)

- O Thou Black Night (1828)

- Shall I Forget... (1828)

- O Gentle Autumn Night (1829)

- Desire (Il desiderio) (1832)

- Venetian Night (1832)

- Say Not That Love Will Pass (1834)

- The Leafy Grove Howls (1834)

- Call Her Not Heavenly (1834)

- I Am Here, Inezilla (1834)

- The Night Review (1836)

- Where Is Our Rose? (1837)

- Will You Not Return (1837 or 1838)

- Doubt (1838)

- The Fire of Longing Burns in My Heart (1838)

- The Night Zephir (1838)

- Sing Not, O Nightingale (1838)

- The Wind Blows (1838)

- Declaration (1839)

- Wedding Song "The North Star" (1839)

- A Farewell to Saint Petersburg (song cycle, 1840, 12 songs)

- How Sweet It Is to Be with You (1840)

- I Recall a Wonderful Moment (1840)

- I Love You, Dear Rose (1842)

- To Her (1843)

- Darling (1847)

- Soon You Will Forget Me (1847)

- Adèle (1849)

- Mary (1849)

- The Gulf of Finland (1850)

- Oh, If I Had Known... (1856)

- Say Not That It Grieves the Heart (1856)