1. Life

Miekichi Suzuki's life, from his early beginnings in Hiroshima to his academic pursuits in Tokyo and his eventual dedication to children's literature, was a journey shaped by personal experiences and a evolving artistic vision.

1.1. Early Life and Education

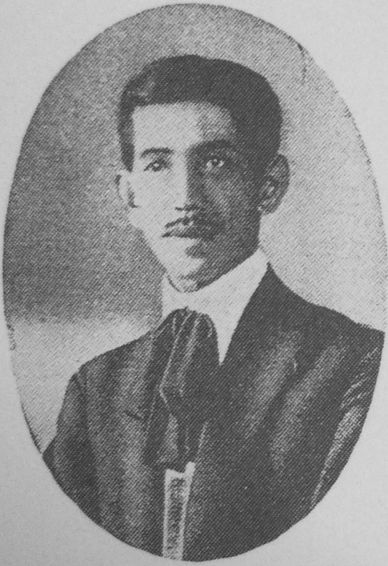

Miekichi Suzuki was born on September 29, 1882, in Sarugaku-cho, Hiroshima (present-day Kamiyacho, Naka-ku, where the Edion Hiroshima Main Store now stands). He was the third son of Etsuji and Fusa Suzuki. In 1889, he began his primary education at Honkawa Elementary School. A significant early life event was the death of his mother, Fusa, when he was nine years old in 1891. Two years later, in 1893, he entered the First Higher Elementary School. In 1896, Suzuki enrolled in Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Junior High School, which is now Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Kokutaiji High School.

Even in his early youth, Suzuki displayed a keen interest in writing. At the age of 15, in 1897, his story "Bōbo o Shitau" (Longing for My Deceased Mother) was published in the April issue of Shōnen Kurabu, followed by "Tenchōsetsu no Ki" in the second issue of Shōkokumin (both magazines published by Hokuryūkan). During this period, he also submitted works to Shinsei and other publications under the pen name Eizan. His talent for children's stories was recognized early; while in his second year of junior high, his fairy tale "Ahō Hato" (Stupid Pigeon) was selected for Shōnen Kurabu.

1.2. Higher Education and Literary Development

In 1901, Suzuki advanced his education, first attending the Third Higher School before enrolling in the Department of English Literature at Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). During his time at the university, he had the opportunity to attend lectures by the renowned author Natsume Sōseki, a pivotal encounter that would significantly influence his literary development.

In 1905, at the age of 23, Suzuki suffered from a nervous breakdown and took a leave of absence from the university to recuperate on Nōmi Island (now part of Etajima City, Hiroshima Prefecture). It was during this period of rest that he found the inspiration for his short story "Chidori." He completed "Chidori" in March 1906 and sent the manuscript to Sōseki, who praised the work and recommended it for publication. The story was subsequently featured in the May issue of Hototogisu. Following this, Suzuki became a central figure among Sōseki's disciples, actively participating in Sōseki's weekly "Thursday Meetings" at his home. This association fostered close relationships with other prominent literary figures of the time, including Kyoshi Takahama, Sōhei Morita, Terada Torahiko, and Kōmiya Toyotaka. In January 1907, his story "Yamahiko" was also published in Hototogisu, and in April of the same year, he published "Chiyogami" through Haishodō.

1.3. Early Literary Career

After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University's Department of Literature in July 1908, a period also marked by the death of his father, Etsuji, Suzuki embarked on a career as an English teacher. He was appointed vice-principal and English instructor at Narita Junior High School in October 1908. While teaching, he continued his literary pursuits, and from March 1910, his full-length novel Kotori no Su (Bird's Nest) was serialized in the Kokumin Shimbun newspaper.

In 1911, at the age of 29, Suzuki resigned from Narita Junior High School and moved to Tokyo, where he took up a position as a lecturer at Kaijo Junior High School. In May of the same year, he married Fuji. The period around 1912 saw a surge in his creative output, with several of his works being published in magazines, and he released novels such as Kaeranu Hi (Days Not Returning) and Omitsu-san. In April 1913, he also began lecturing at Chuo University. From July of that year, his novel Kuwa no Mi (Mulberry Fruit) was serialized in the Kokumin Shimbun and later published by Shunyodo in January 1914, solidifying his reputation as a novelist.

However, despite his growing recognition, Suzuki began to feel a creative impasse in his novel writing. In March 1915, he started the publication of his Miekichi Zensakushu (Complete Works of Miekichi), which eventually ran to 13 volumes. In April of the same year, he published "Hachi no Baka" in Chūō Kōron. Recognizing his limitations as a novelist, he decided to cease writing novels after 1915.

A significant turning point occurred in 1916 when his eldest daughter, Suzu, was born to Raku Kawakami. Inspired to write for her, he created the fairy tale collection Kosui no Onna (Woman of the Lake), which marked his transition to children's literature. Tragically, his wife, Fuji, passed away in July 1916. The following year, in April 1917, he commenced the publication of Sekai Dōwa Shū (World Fairy Tale Collection), with Kiyoshi Shimizu handling the design and illustrations. This collaboration forged a lasting friendship that would prove instrumental in the launch of Akai Tori. In January 1918, his eldest son, Sankichi, was born.

2. Akai Tori and the Children's Literature Movement

Miekichi Suzuki's most profound and lasting contribution to Japanese culture was his initiation and leadership of the children's literature movement through the magazine Akai Tori.

2.1. Founding and Philosophy of Akai Tori

In June 1918, Miekichi Suzuki launched Akai Tori (Red Bird), a pioneering children's literary magazine. Just a few months later, in September, he resigned from Kaijo Junior High School and took a leave of absence from Chuo University to dedicate himself fully to the magazine. The establishment of Akai Tori stemmed from Suzuki's realization that children's literature in Japan at the time was predominantly didactic, focusing heavily on moral instruction and rote learning. He sought to revolutionize this by creating a magazine that offered children authentic literary and artistic experiences.

The core philosophy of Akai Tori was to emphasize learning through observation and direct experience, contrasting sharply with the traditional reliance on memorization and ceremonial language. Suzuki believed in the power of "everyday language" to connect with children and reflect their lived realities, promoting its use over formal or archaic expressions. His vision was to elevate children's literature artistically, transforming it from mere instructional tools into works of genuine literary merit and beauty. He aimed to cultivate a sense of wonder and creativity in young readers, encouraging them to engage with stories and poems that resonated with their imagination and experiences, rather than simply imparting lessons.

2.2. Notable Contributors and Works

Akai Tori quickly became a crucible for artistic children's literature, attracting contributions from many of Japan's most celebrated literary figures of the Taishō period. Suzuki actively solicited works from established writers, drawing in an impressive roster of talents. Initial supporters included literary giants such as Kyōka Izumi, Kaoru Osanai, Shūsei Tokuda, Kyoshi Takahama, Toyoichirō Nogami, Yaeko Nogami, Kōmiya Toyotaka, Ikuma Arishima, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Hakushū Kitahara, Tōson Shimazaki, Mori Ōgai, and Sōhei Morita. Over time, the list expanded to include other prominent figures such as Mimei Ogawa, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Masao Kume, Mantarō Kubota, Takeo Arishima, Ujaku Akita, Yaso Saijō, Haruo Satō, Kan Kikuchi, Rofū Miki, Kōsaku Yamada, Tamezō Narita, and Hidemaro Konoe.

The magazine became the birthplace of numerous masterpieces in children's literature. Among the most famous contributions were Ryūnosuke Akutagawa's children's story "Kumo no Ito" (The Spider's Thread) and Takeo Arishima's "Hitofusa no Budō" (A Bunch of Grapes). Kitahara Hakushū contributed a variety of children's songs (dōyō), while Osanai Kaoru and Kubota Mantarō penned children's plays. Akai Tori also served as a crucial platform for emerging talents in children's literature, with writers like Jōji Tsubota and Nankichi Niimi frequently publishing their works in its pages. Notably, Niimi's celebrated story "Gon Gitsune" (Gon, the Little Fox) was written when he was just 18, demonstrating the magazine's success in discovering and nurturing young authors who would later achieve widespread acclaim.

2.3. Impact and Conclusion of Akai Tori

Akai Tori had a profound and lasting impact on the Japanese children's literature movement. Published for 17 years, it saw a total of 196 issues. During its heyday, the magazine's circulation reportedly exceeded 30,000 copies. The actual readership was estimated to be significantly higher, as issues purchased by schools and rural youth associations were often shared and read collectively, broadening its reach and influence far beyond its direct sales figures.

The magazine played a crucial role in cultivating and discovering new talents across various fields of children's culture. It provided a platform for new children's authors such as Jōji Tsubota and Nankichi Niimi, dōyō lyricists like Tatsumi Seika, dōyō composers like Tamezō Narita and Shin Kusakawa, and children's illustrators such as Kiyoshi Shimizu. Additionally, Akai Tori famously included a dedicated section for children's submissions, where Miekichi Suzuki, Kitahara Hakushū, and Kan Yamamoto served as judges, providing feedback and encouragement. This initiative resonated strongly with the burgeoning child-respecting education movement of the time, fostering a sense of value and agency among young readers and aspiring writers.

The publication of Akai Tori ceased with its August 1936 issue, following Suzuki's death. A special commemorative issue, Akai Tori Suzuki Miekichi Tsui-tō-gō (Akai Tori: Miekichi Suzuki Memorial Issue), was published in October 1936, marking the definitive conclusion of the magazine's influential run.

3. Major Works

Miekichi Suzuki's literary output spanned various genres, from novels to children's stories and translations. His principal works and compiled collections include:

- Chiyogami (千代紙, 1907)

- Onna to Akai Tori (女と赤い鳥, Woman and Red Bird, 1911)

- Omitsu-san (おみつさん, 1912)

- Kaeranu Hi (返らぬ日, Days Not Returning, 1912)

- Kotori no Su (小鳥乃巣, Bird's Nest, 1912)

- Kushi (櫛, Comb, 1913)

- Onna Bato (女鳩, Female Pigeon, 1913)

- Kiri no Ame (桐の雨, Paulownia Rain, 1913)

- Kuwa no Mi (桑の実, Mulberry Fruit, 1914)

- Asagao (朝顔, Morning Glory, 1914)

- Akai Tori (赤い鳥, Red Bird, 1915) - A work by Suzuki, distinct from the magazine.

- Zange (懺悔, Confession, 1915) - A translation of Maxim Gorky's work.

- Miekichi Zensakushu (三重吉全作集, Complete Works of Miekichi, 13 volumes, 1915-1916)

- Kosui no Onna (湖水の女, Woman of the Lake, 1916)

- Sekai Dōwa Shū (世界童話集, World Fairy Tale Collection, 1917)

- Kojiki Monogatari (古事記物語, The Tale of Kojiki, 1920) - A simplified, narrative version of the classic Kojiki for children, later widely accepted by adults for its readability.

- Kyūgotai (救護隊, Rescue Team, 1921)

- Andersen Dōwashū (アンデルセン童話集, Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1927) - A translation of Hans Christian Andersen's works.

- Nihon Kenkoku Monogatari (日本建国物語, Story of Japan's Founding, 1930)

- Gendai Nihon Bungaku Zenshu Dai 42 Hen: Suzuki Miekichi Shū, Morita Sōhei Shū (現代日本文学全集 第42篇 鈴木三重吉集・森田草平集, Collection of Modern Japanese Literature Vol. 42: Suzuki Miekichi Collection, Sōhei Morita Collection, 1930)

- Chidori (千鳥, 1935)

- Tsuzurikata Tokuhon (綴方読本, Composition Reader, 1935)

- Suzuki Miekichi Zenshū (鈴木三重吉全集, Complete Works of Miekichi Suzuki, 6 volumes, 1938)

- Miekichi Dōwa Tokuhon (三重吉童話読本, Miekichi's Fairy Tale Reader, 10 volumes, 1948-1949)

- Suzuki Miekichi Dōwa Zenshū (鈴木三重吉童話全集, Complete Collection of Miekichi Suzuki's Fairy Tales, 9 volumes with 1 supplementary volume, 1975)

- Suzuki Miekichi Zenshū (鈴木三重吉全集, Complete Works of Miekichi Suzuki, 6 volumes with 1 supplementary volume, 1982)

4. Philosophy and Beliefs

Miekichi Suzuki's philosophy was rooted in a progressive vision for children's education and literature, seeking to foster natural curiosity and artistic appreciation over rigid instruction. He strongly believed that children's literature should be an art form in itself, moving away from the didactic and morally prescriptive narratives that dominated the field in his time.

A cornerstone of his philosophy, especially evident in Akai Tori, was the emphasis on "learning from observation and experience." He advocated for stories and content that reflected the world children lived in, using "everyday language" to make literature accessible and relatable. This approach aimed to encourage children to engage with their surroundings actively and cultivate their own understanding, rather than passively absorbing pre-digested lessons. Suzuki's efforts to bring artistic integrity to children's works, inviting leading literary figures to contribute, underscored his belief that children deserved the highest quality of storytelling.

Beyond literature, Suzuki also pursued holistic child development. In 1928, he established the Kidō Shōnen-dan (Boy Scouts of Chivalry), an organization dedicated to the spiritual education of boys through horsemanship. This initiative reflected his broader conviction that education should encompass not just intellectual growth but also moral and physical development, fostering well-rounded individuals. His work in both literary and practical education demonstrated his commitment to a comprehensive child-respecting pedagogy, which sought to empower children's voices and creativity.

5. Personal Life and Relationships

Miekichi Suzuki's personal life was intertwined with his literary endeavors, marked by familial bonds and complex relationships within the vibrant artistic circles of his era.

Suzuki was married twice. His first marriage was to Fuji in May 1911. Sadly, Fuji passed away in July 1916. In October 1921, Suzuki remarried to Hama Koizumi. He had two children: a daughter named Suzu, born in 1916 from his relationship with Raku Kawakami, and a son named Sankichi, born in January 1918.

His personal life was deeply connected to his literary network. As a central figure among Natsume Sōseki's disciples, he formed close friendships with prominent writers such as Kyoshi Takahama, Sōhei Morita, Terada Torahiko, and Kōmiya Toyotaka. These relationships not only provided intellectual camaraderie but also formed the backbone of the collaborative spirit behind Akai Tori, where many of his literary friends contributed their works.

5.1. Personality and Anecdotes

Miekichi Suzuki possessed a complex personality, characterized by both passionate dedication to his work and notably volatile personal habits, particularly concerning alcohol. He was known to be a heavy drinker, capable of consuming an astounding 1 L of sake in a single evening. Accounts from his contemporaries describe his behavior when intoxicated as uncontrollable, often leading to fierce arguments where "ashtrays would fly."

One anecdote shared by Satomi Ton in his essays recounts an incident where Suzuki, in a drunken rage, severely admonished Satomi for referring to Kyōka Izumi as "Izumi-san" rather than using a more respectful honorific, despite Izumi not being Satomi's direct mentor. This highlights Suzuki's intense personality and perhaps his strong opinions on literary decorum.

The author Masajirō Kojima, in his work Ganchū no Hito (The Person in My Eye), candidly depicted Suzuki's heavy drinking and the reality of "ghostwriting" (代作, daisaku) within the Akai Tori magazine, where some content attributed to famous authors was actually penned by others, often Kojima himself. While this practice was not uncommon in literary circles of the time, Kojima's account sheds light on the internal workings and compromises of the magazine's production.

A well-known conflict also arose between Suzuki and his long-time collaborator, Kitahara Hakushū, who was a key contributor to Akai Tori. The prevailing theory suggests that their friendship deteriorated into a state of estrangement after 1933 due to a quarrel fueled by alcohol. However, a letter from Suzuki to Nobukichi Nagashima indicates that Hakushū's frequent delays in submitting manuscripts were the true cause of their falling out. The exact details of their separation remain unclear, even to those close to them at the time, leading to various speculations, though it is often attributed to a fundamental misunderstanding or clash of personalities amplified by their respective habits.

6. Death

Miekichi Suzuki's pioneering career in children's literature came to an end with his death on June 27, 1936. His health had begun to decline in October 1935 when he fell ill with asthma while working on Tsuzurikata Tokuhon in Kobuchizawa, Yamanashi Prefecture. His condition worsened significantly, leading to his admission to the Manabe Internal Medicine Department of Tokyo Imperial University Hospital on June 24, 1936.

Suzuki passed away at 6:30 AM on June 27, 1936, at the age of 53, due to lung cancer. His Buddhist posthumous name is Tenshin-in Keiteki Nichijū Koji. A farewell ceremony for him was held at his home in Nishi-Ōkubo on June 29.

His death had an immediate and profound impact on the literary world, particularly on Akai Tori. The magazine, which had been his life's work, ceased publication with its August 1936 issue following his passing. In October 1936, a special memorial issue titled Akai Tori: Miekichi Suzuki Tsui-tō-gō was released, serving as a final tribute to his immense contributions.

7. Assessment and Legacy

Miekichi Suzuki is remembered as a transformative figure in Japanese literature and culture, whose work laid the foundation for modern children's literature. His legacy is complex, encompassing both widespread acclaim for his innovative contributions and candid discussions of his personal struggles.

7.1. Positive Assessment and Contributions

Suzuki is widely celebrated as the "Father of the Japanese Children's Culture Movement", a title that underscores the profound impact he had on the artistic and educational landscape for young people in Japan. His greatest achievement, the founding of Akai Tori, marked a revolutionary departure from the predominantly didactic children's books of the time. Through Akai Tori, he championed an artistic approach to children's literature, emphasizing imagination, observation, and the use of everyday language, thereby elevating the genre to a new level of literary merit.

Over its 17-year run, Akai Tori published 196 issues, showcasing countless original stories, poems, and plays. Suzuki's innovative spirit extended to actively seeking out and nurturing new literary and artistic talent. He provided a crucial platform for many aspiring authors, including future renowned figures such as Jōji Tsubota and Nankichi Niimi, whose celebrated story "Gon, the Little Fox" was published in Akai Tori when Niimi was just 18. The magazine also fostered the careers of dōyō (children's song) lyricists like Tatsumi Seika, composers such as Tamezō Narita and Shin Kusakawa, and illustrators like Kiyoshi Shimizu. His inclusion of a children's submission section, personally judged by himself and other prominent literary figures, fostered a sense of respect for children's voices and significantly influenced the "child-respecting education movement" of the era.

Beyond the magazine, his work Kojiki Monogatari, a retelling of the classic Kojiki for children in modern, accessible language, stands as a testament to his commitment to making traditional Japanese culture relatable to younger generations. This work proved remarkably popular, reaching a wide audience of both children and adults due to its clarity and engaging narrative.

To commemorate his enduring influence, the Suzuki Miekichi Award was established in 1948, on the 13th anniversary of his death. This prestigious award continues to be presented annually to children across Japan for their outstanding compositions and poetry, ensuring that Suzuki's legacy of nurturing young talent and promoting quality children's literature lives on.

7.2. Criticisms and Controversies

While Miekichi Suzuki is largely celebrated for his contributions, his legacy is not without its critical perspectives and controversies, primarily stemming from aspects of his personal life and the operational practices of Akai Tori.

Suzuki was known for his severe alcoholism and contentious behavior when drunk. Accounts from his contemporaries describe him as a "heavy drinker" whose consumption could lead to volatile outbursts, including "ashtrays flying" during arguments. The writer Satomi Ton recounted an incident where Suzuki, under the influence, vehemently chastised him for a perceived lack of respect in addressing a senior literary figure. Such anecdotes reveal a passionate but sometimes difficult personality, which could cause friction within his literary circles.

Another point of discussion concerns the practice of "ghostwriting" (代作, daisaku) for Akai Tori. While it was common practice in Japanese literary magazines of the era for assistants or younger writers to produce material under the names of more famous authors, Masajirō Kojima's memoir Ganchū no Hito explicitly detailed his own role in ghostwriting for Suzuki, often when Suzuki was too incapacitated by drink to produce content himself. This raises questions about the authenticity of all works published under the names of renowned contributors, although it does not diminish Suzuki's role as the editor and driving force behind the magazine's artistic direction.

Furthermore, Suzuki's personal habits led to notable conflicts, such as his eventual estrangement from Kitahara Hakushū, a key collaborator and contributor to Akai Tori. While popular belief attributes their separation to a drunken quarrel, Suzuki's own letters suggest that Hakushū's frequent delays in manuscript submission were the underlying cause. The exact reasons for this significant rupture remain somewhat ambiguous, though it highlights the challenges Suzuki faced in managing the high demands of his ambitious literary project alongside his personal struggles. These critical perspectives offer a more nuanced understanding of Suzuki, acknowledging his human frailties alongside his immense cultural achievements.

8. Commemoration and Memorials

Miekichi Suzuki's enduring legacy is honored through several memorials and commemorative activities throughout Japan.

His birthplace in Hiroshima, specifically in Sarugaku-cho (now part of Kamiyacho, Naka-ku, the site of the Edion Hiroshima Main Store), is marked by a commemorative monument affixed to the building's wall.

A significant literary monument dedicated to him stands near the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (close to the Atomic Bomb Dome). This monument, sculpted by Katsuzō Enami, bears an inscription that reads: "I will forever have dreams / only, not suffering for them as deeply as in my youth." This quote reflects Suzuki's deep philosophical connection to hope and innocence.

Suzuki's remains are interred in the Suzuki family grave at Chōonji Temple in Hiroshima. Next to the family grave, a specific grave marker for Miekichi Suzuki was erected on the 13th anniversary of his death. The inscription on this grave marker, "Miekichi Eimin no Chi Miekichi to Hama no Haka" (Miekichi's eternal resting place, the grave of Miekichi and Hama), was personally written by Suzuki before his passing, underscoring his lasting connection to his family and his final resting place.

Beyond physical monuments, his memory is kept alive through the prestigious Suzuki Miekichi Award. Established in 1948, this award continues to recognize and encourage young literary talent in Japan, providing a tangible link between Suzuki's pioneering efforts and future generations of writers. The "Suzuki Miekichi Akai Tori no Kai" (Miekichi Suzuki Akai Tori Association) also exists, dedicated to preserving and promoting children's literature in the spirit of his work.