1. Overview

Masaki Kobayashi (小林 正樹Kobayashi MasakiJapanese, February 14, 1916 - October 4, 1996) was a highly acclaimed Japanese film director and screenwriter renowned for his profound social commentary and humanistic themes. His works often critically examined societal issues, the impact of war, and the resilience of human dignity under oppressive systems, establishing him as a significant voice in Japanese cinema of the 1950s and 1960s.

Kobayashi's filmography includes the epic trilogy The Human Condition (1959-1961), a nearly ten-hour exploration of a pacifist's struggles during World War II, which is one of the longest fiction films ever made for theatrical release. He is also celebrated for his samurai films Harakiri (1962) and Samurai Rebellion (1967), which deconstructed traditional samurai ethics, and the visually stunning horror anthology Kwaidan (1964). His films garnered significant international recognition, earning awards at prestigious festivals such as Cannes and Venice, and an Academy Award nomination for Kwaidan. Kobayashi's dedication to exploring deep ethical questions and his distinctive artistic style solidified his legacy as a master filmmaker committed to social critique.

2. Early Life and Education

Masaki Kobayashi was born on February 14, 1916, in Otaru, a port city on the island of Hokkaido, Japan. His family belonged to the upper-middle class; his father, Yuichi, worked for Mitsui & Co., and his mother, Hisako, came from a merchant family. He had two older brothers and a younger sister. The Kobayashi family traced its lineage to a samurai from Shimonoseki. Although he lived in Tokyo during his elementary school years, Kobayashi spent most of his childhood in Otaru until the age of 17. His household was characterized by warmth and tolerance, with his parents actively encouraging his exploration of the arts. He first experienced cinema at the age of seven and frequently attended movies, art exhibitions, concerts, and theater performances with his mother. His older brother, Yasuhiko, who participated in film study groups at university, further nurtured Kobayashi's understanding of film.

In 1938, Kobayashi enrolled in Waseda University in Tokyo, where he pursued studies in East Asian art and philosophy. A pivotal influence during his university years was Aizu Yaichi, a distinguished poet and historian who became Kobayashi's mentor. Aizu specialized in Buddhist art, particularly that of the Nara period, and often took his class to Buddhist temples. Kobayashi frequently accompanied Aizu on trips to Nara and visited Aizu's home, deeply absorbing Aizu's perspectives on life and art. His thesis focused on Murō-ji, a Buddhist temple in Nara, for which he spent a month living at the temple to research its history. Kobayashi later worked on a documentary about Aizu, released in 1996.

During his time at Waseda University, Kobayashi would visit Shochiku Studio to observe his second cousin, the acclaimed actress Kinuyo Tanaka, at work. It was during this period that he developed a strong desire to become a film director. After graduating from Waseda University in 1941, Kobayashi joined Shochiku as a director-in-training for eight months. He assisted Hiroshi Shimizu on Dawn Chorus and Hideo Ōba on Kaze kaoru niwa. During this early period, Kobayashi also began writing a book set in Nara, centered on an Oriental art scholar who enlists in the army.

3. Wartime Experience

In January 1942, Masaki Kobayashi was conscripted into the Azabu Third Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army. After completing three months of training as a heavy machine gunner, he was deployed near Harbin in Manchuria. In September 1943, his squad was assigned to patrol along the Ussuri river. In June 1944, his regiment returned to Japan, with orders to transfer to the Philippines. However, due to the presence of Allied submarines, the Azabu Third Regiment was unable to reach the Philippines and was instead diverted to Miyako-jima in the Ryukyu Islands, where they remained until the end of the war. During their deployment on Miyako-jima, Kobayashi's group was involved in constructing an airfield. Conditions on the island were harsh, with his unit often resorting to eating grasshoppers and dogs to survive.

Throughout his military service, Kobayashi maintained a diary, which meticulously documented his wartime experiences and included an I-novel reflecting on the loss of his youth. While his diary expressed support for the Japanese war effort, it also conveyed his deep lament for the death and destruction caused by the war. Notably, Kobayashi never participated in frontline combat during his time in the army. He identified himself as a pacifist and a socialist, and as a form of personal resistance, he consistently refused promotion to any rank higher than private.

Following Japan's surrender, Kobayashi spent nearly a year as a prisoner of war in a labor camp in Kadena, Okinawa. During his internment, he organized and ran a theater company with other inmates, producing several shows. He was finally released from the labor camp in November 1946. Upon returning home, Kobayashi learned of profound personal losses: his father had died in 1945, and his older brother, Yasuhiko, had been killed in battle in China in 1944.

4. Film Career

Masaki Kobayashi's film career spanned several decades, marked by a distinctive style and a consistent focus on social critique and humanistic themes. His journey began in the studio system, evolved through a period of critical acclaim for his epic and genre-defying works, and continued into later years with documentaries and ambitious, though sometimes unrealized, projects.

4.1. Entry into Shochiku and Assistant Directing

After his release from the prisoner of war camp and his return to Japan in 1946, Kobayashi rejoined Shochiku as an assistant director. He was initially assigned to assist Keisuke Sasaki before being transferred to work under the acclaimed director Keisuke Kinoshita. Kobayashi developed a deep admiration for Kinoshita's compassion, intelligence, and directorial skill, and the two formed a strong bond over their shared wartime experiences and the deaths of their mothers.

Kobayashi's first role under Kinoshita was as a second assistant director on Phoenix in 1947. By 1948, he was promoted to chief assistant director for Apostasy, a position he maintained throughout his tenure as Kinoshita's assistant. In 1949, Kobayashi collaborated with Kinoshita to co-script Broken Drum. His final film as Kinoshita's assistant was A Japanese Tragedy, released in 1953. In the same year, Kinoshita began actively seeking material suitable for Kobayashi's directorial debut, even purchasing the rights to the novel Jinkō Teien with that intention, though Kinoshita himself would later adapt it into the 1954 film The Garden of Women.

4.2. Early Directorial Works and Social Critique

Masaki Kobayashi made his directorial debut in 1952 with My Son's Youth (息子の青春Musuko no SeishunJapanese), a short film released as part of Shochiku's "sister films" initiative, which aimed to introduce new directors. On April 1, 1952, Kobayashi married Chiyoko Fumiya, an actress at Shochiku. His first feature-length film, Sincerity (まごころMagokoroJapanese), was released in 1953, with a screenplay penned by his mentor, Keisuke Kinoshita. Both My Son's Youth and Sincerity drew inspiration from Kobayashi's own family and childhood, with some characters modeled after his relatives.

In 1953, Kobayashi completed filming The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋Kabe Atsuki HeyaJapanese), a powerful and critical work about Class B and Class C war criminals held in Sugamo Prison. Based on the diaries of actual war criminals, the film represented a significant departure from the typical productions of Shochiku at the time. Shochiku initially refused to release the film without alterations, fearing that its critique of the Allied occupation of Japan would displease the United States. Kobayashi, however, staunchly refused to make any cuts, resulting in the film's delayed release until 1956. This stand hurt Kobayashi's reputation within Shochiku, prompting him to make his subsequent four films more aligned with the studio's conventional style in an effort to reestablish himself.

These more conventional films included Three Loves (三つの愛Mittsu no AiJapanese), released in 1954, which notably featured scenes shot inside the same church where Kobayashi and Chiyoko Fumiya had been married. Later in 1954, Somewhere Under the Broad Sky (この広い空のどこかにKono Hiroi Sora no Dokoka niJapanese) was released, marking the first appearance of Keiji Sada in a Kobayashi-directed film. Sada, a close friend of Kobayashi, would go on to star in six of his films. Fountainhead (泉IzumiJapanese), released in 1956, was the last of Kobayashi's films to strongly resemble the typical Shochiku style.

After The Thick-Walled Room was finally released to the public in 1956, Kobayashi continued to explore social issues. Later that year, I Will Buy You (あなた買いますAnata KaimasuJapanese) was released, exposing corruption in baseball scouting. In 1957, Black River (黒い河Kuroi KawaJapanese) depicted the crime and prostitution that emerged around US military bases in Japan during and after the American occupation. This film marked the first major role for Tatsuya Nakadai in a Kobayashi-directed work; Nakadai would become a frequent collaborator, starring in nine of Kobayashi's next thirteen films.

4.3. Major Works and International Acclaim

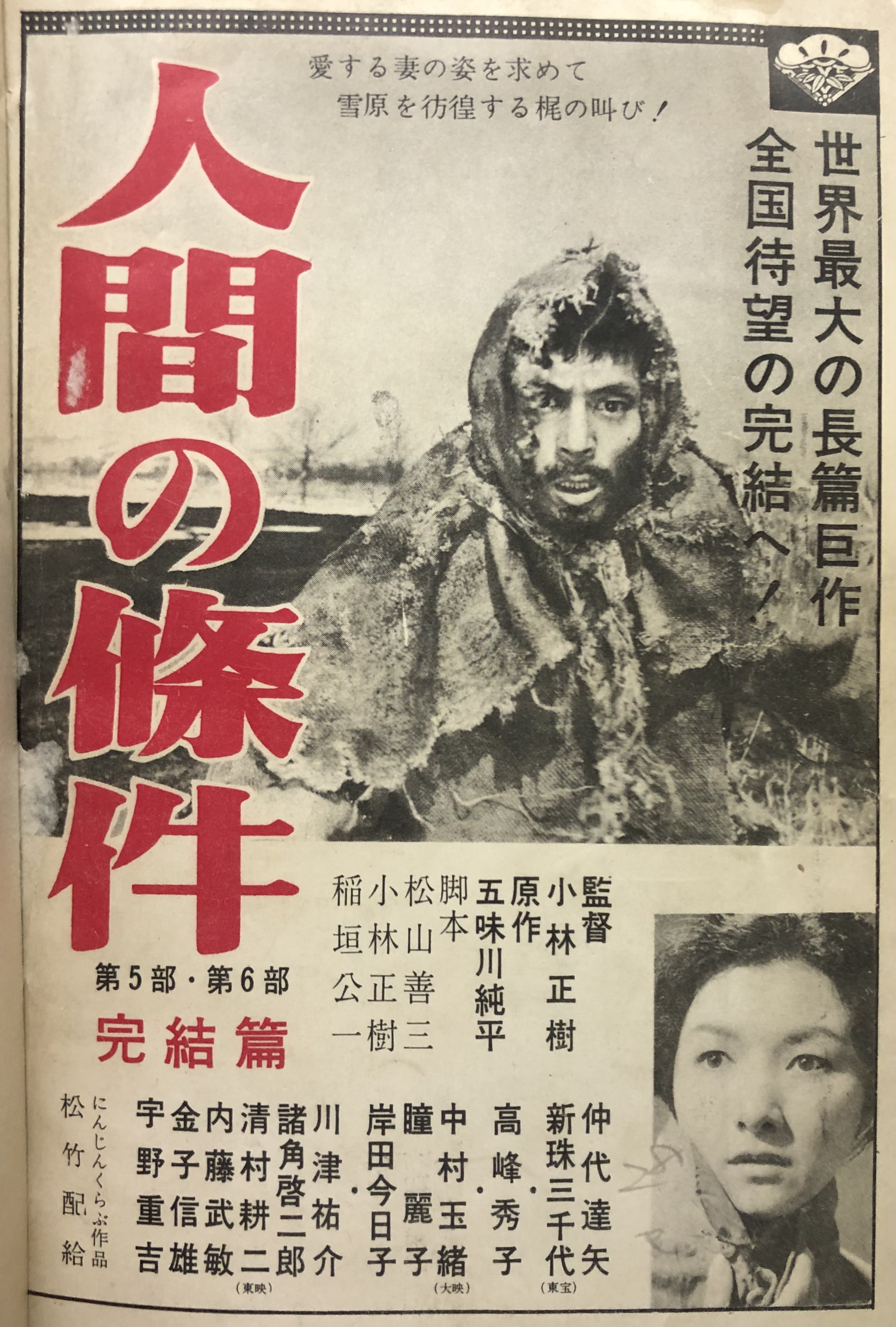

Masaki Kobayashi's most celebrated period of filmmaking began in the late 1950s, marked by ambitious projects that earned him widespread international acclaim. From 1959 to 1961, he directed The Human Condition (人間の條件Ningen no JōkenJapanese), an epic trilogy that explores the devastating effects of World War II on a Japanese pacifist and socialist named Kaji. The complete series, comprising six parts, spans nearly ten hours, making it one of the longest fiction films ever produced for theatrical release. The film vividly portrays the brutality of the Japanese military during the war, Kaji's resistance as an intellectual soldier, his subsequent hardships, and his ultimate fate. The trilogy received significant accolades, including the Mainichi Film Award for Best Film and Mainichi Film Award for Best Director in 1961 (for A Soldier's Prayer), and the San Giorgio Prize and Pasinetti Award at the Venice Film Festival in 1960.

In 1962, Kobayashi directed Harakiri (切腹SeppukuJapanese), his first jidaigeki (period drama). Based on Yasuhiko Takiguchi's novel Ibun Roninki with a screenplay by Shinobu Hashimoto, the film is a powerful critique of the rigid and hypocritical samurai code. Kobayashi himself considered Harakiri to be his most "dense" work. It earned the prestigious Jury Prize at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival, cementing his international reputation.

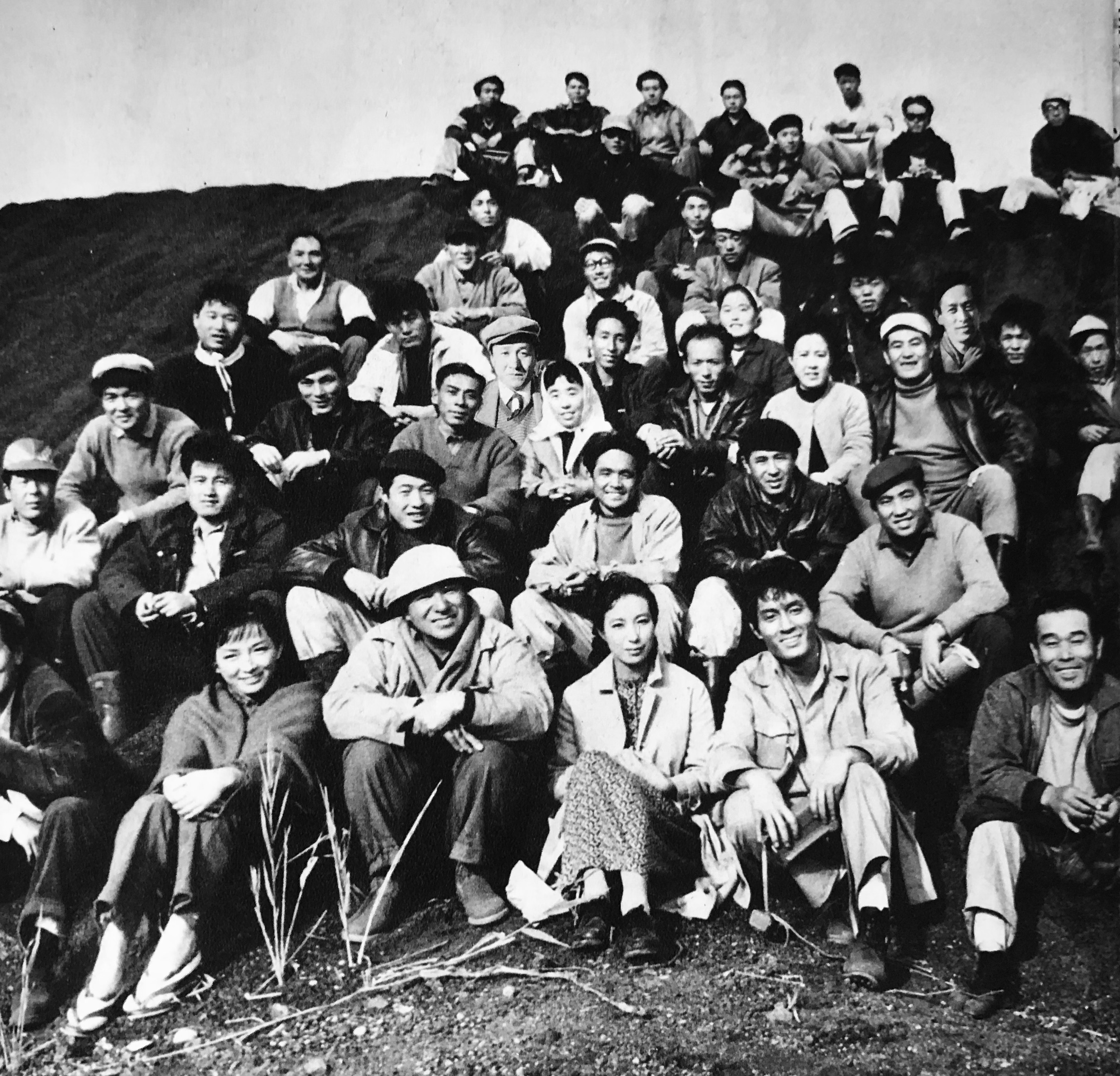

His next major work, Kwaidan (怪談KaidanJapanese), released in 1964, marked his first venture into color filmmaking. This anthology film comprises four distinct ghost stories drawn from the writings of Lafcadio Hearn. Kwaidan received the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The film was praised globally for its stunning visuals, which were achieved through large-scale sets built inside a disused aircraft hangar, featuring elaborate painted skies and artistic designs by Shigemasa Toda. The haunting and innovative score by Tōru Takemitsu further enhanced its fantastical atmosphere. However, the extensive production, long filming period, and large cast and crew (totaling 800 people) led to significant cost overruns, ultimately causing the independent production company Bungei Production Ninjin Club to incur substantial debt and declare bankruptcy.

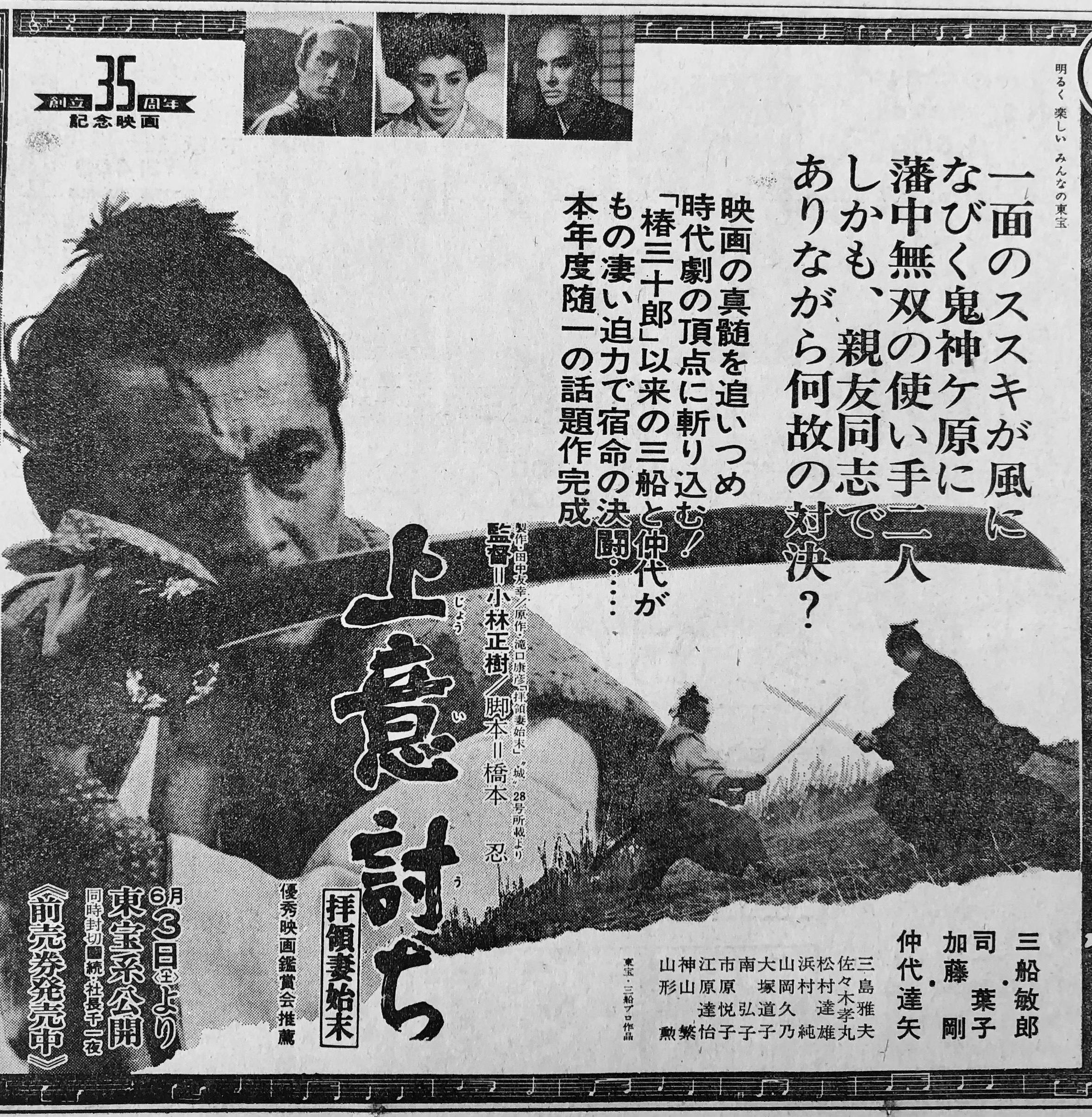

In 1967, Kobayashi directed Samurai Rebellion (上意討ち 拝領妻始末Jōi-uchi: Hairyō Tsuma ShimatsuJapanese), his first film after leaving Shochiku, produced by Toshiro Mifune's Mifune Productions. This film, another powerful jidaigeki, also received critical acclaim, winning the FIPRESCI Prize at the Venice Film Festival, and being named Best Film and Best Director by Kinema Junpo and Best Film by the Mainichi Film Awards in 1967.

4.4. Later Career and Projects

In 1968, Masaki Kobayashi, along with fellow esteemed directors Akira Kurosawa, Keisuke Kinoshita, and Kon Ichikawa, formed the directors' group Shiki no Kai (四騎の会Shiki no KaiJapanese, "The Four Horsemen Club"). This initiative aimed to create films that would resonate with younger generations.

In 1969, Kobayashi was invited to serve as a member of the jury at the 19th Berlin International Film Festival. He was also considered as a candidate to direct the Japanese sequences for the Hollywood production Tora! Tora! Tora! after Akira Kurosawa's departure from the project, though the role ultimately went to Kinji Fukasaku and Toshio Masuda.

In his later career, Kobayashi continued to direct feature films, including Hymn To A Tired Man (日本の青春Nihon no SeishunJapanese, 1968), Inn Of Evil (いのちぼうにふろうInochi Bō ni FurōJapanese, 1971), and The Fossil (化石KasekiJapanese, 1975), which was both a television drama and a film adaptation of a Yasushi Inoue novel. He also directed Burning Autumn (燃える秋Moeru AkiJapanese, 1978). His final feature film was The House Without a Meal Table (食卓のない家Shokutaku no Nai IeJapanese, 1985), based on Fumiko Enchi's novel about the United Red Army incident.

One of Kobayashi's most significant later works was the documentary Tokyo Trial (東京裁判Tōkyō SaibanJapanese, 1983). This ambitious project took five years to complete, meticulously compiling footage from the US Department of Defense archives and various international newsreels to chronicle the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. While the film received positive evaluations from some critics, it also faced criticism for its inclusion of footage from the Chinese Nationalist Government's The Roar of China concerning the Nanjing Massacre, which was questioned for its historical accuracy, despite the film explicitly crediting it as a "Chinese film" to maintain neutrality. Tokyo Trial won the Blue Ribbon Award for Best Film in 1983.

Kobayashi harbored a long-standing ambition to adapt Yasushi Inoue's novel Tun Huang into a film, and he completed the screenplay for it. However, creative differences over the film's direction with Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the president of the newly established Daiei studio, forced him to abandon the project. In his final years, he was also preparing a biographical film about his university mentor, Aizu Yaichi, but passed away before its completion.

5. Thematic Concerns and Artistic Style

Masaki Kobayashi's filmography is deeply characterized by recurring thematic concerns and a distinctive artistic style that set him apart as a filmmaker of profound social and ethical inquiry. Central to his work is a relentless critique of war and its devastating impact on individuals and society. Films like The Human Condition trilogy vividly illustrate the moral compromises, dehumanization, and suffering inflicted by military systems, reflecting Kobayashi's personal experiences as a pacifist conscript during World War II. He consistently explored the loss of innocence and the struggle to maintain one's humanity amidst brutal conflict.

Beyond war, Kobayashi frequently examined the broader themes of human dignity under oppressive systems and the pervasive nature of social injustice. His films often exposed the corruption, hypocrisy, and rigid hierarchies within Japanese society. The Thick-Walled Room directly challenged the official narrative of war criminals, while Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion meticulously deconstructed the revered samurai code, revealing its inherent cruelty and the suppression of individual freedom in the name of honor and duty. Black River delved into the moral decay and exploitation in post-war Japan, particularly around US military bases. Kobayashi's perspective consistently highlighted the plight of individuals who resist or are victimized by powerful, often unseen, forces.

Artistically, Kobayashi's films are marked by a distinctive visual style and narrative techniques. He often employed a formal, almost theatrical, aesthetic, characterized by carefully composed shots, deep focus, and a deliberate pace that amplified the dramatic tension and emotional weight of his narratives. His use of stark contrasts, particularly in black and white films like Harakiri, created a powerful visual language that underscored the moral ambiguities and harsh realities depicted. In Kwaidan, his first color film, he utilized vibrant, stylized colors and elaborate sets to create a surreal and immersive atmosphere, transforming traditional ghost stories into visually stunning and psychologically resonant experiences. Kobayashi's masterful control over mise-en-scène and his ability to craft compelling narratives that engaged with complex social and ethical questions solidified his reputation as a filmmaker deeply committed to exploring the human condition.

6. Filmography

Masaki Kobayashi directed the following films:

- My Son's Youth (息子の青春Musuko no SeishunJapanese) (1952)

- Sincerity (まごころMagokoroJapanese) (1953)

- Somewhere Under the Broad Sky (この広い空のどこかにKono Hiroi Sora no Dokoka niJapanese) (1954)

- Three Loves (三つの愛Mittsu no AiJapanese) (1954)

- Beautiful Days (美わしき歳月Uruwashiki SaigetsuJapanese) (1955)

- The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋Kabe Atsuki HeyaJapanese) (1956)

- I Will Buy You (あなた買いますAnata KaimasuJapanese) (1956)

- Fountainhead (泉IzumiJapanese) (1956)

- Black River (黒い河Kuroi KawaJapanese) (1957)

- The Human Condition I: No Greater Love (人間の條件 第一・第二部Ningen no Jōken Dai-ichi, Dai-nibuJapanese) (1959)

- The Human Condition II: Road to Eternity (人間の條件 第三・第四部Ningen no Jōken Dai-san, Dai-yonbuJapanese) (1959)

- The Human Condition III: A Soldier's Prayer (人間の條件 完結篇Ningen no Jōken Kanketsu-henJapanese) (1961)

- The Inheritance (からみ合いKarami-aiJapanese) (1962)

- Harakiri (切腹SeppukuJapanese) (1962)

- Kwaidan (怪談KaidanJapanese) (1964)

- Samurai Rebellion (上意討ち 拝領妻始末Jōi-uchi: Hairyō Tsuma ShimatsuJapanese) (1967)

- Hymn To A Tired Man (日本の青春Nihon no SeishunJapanese) (1968)

- Inn Of Evil (いのちぼうにふろうInochi Bō ni FurōJapanese) (1971)

- The Fossil (化石KasekiJapanese) (1975)

- Burning Autumn (燃える秋Moeru AkiJapanese) (1978)

- Tokyo Trial (東京裁判Tōkyō SaibanJapanese) (1983, documentary)

- The House Without a Meal Table (食卓のない家Shokutaku no Nai IeJapanese) (1985)

Other notable works:

- Broken Drum (破れ太鼓Yabure DaikoJapanese) (1949) - Co-scripted with Keisuke Kinoshita.

- Dodes'ka-den (どですかでんDodesukadenJapanese) (1970) - Planning.

- Dora-heita (どら平太Dora-heitaJapanese) (2000) - Screenplay (released posthumously).

7. Awards and Honors

Masaki Kobayashi received numerous domestic and international awards and honors throughout his distinguished career:

| Year | Name of Award or Honor | Awarding Organization | Country of Origin | Film Title (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | San Giorgio Prize | Venice Film Festival | Italy | The Human Condition |

| Pasinetti Award | ||||

| 1961 | Best Film | Mainichi Film Awards | Japan | A Soldier's Prayer |

| Best Director | ||||

| 1962 | Best Film | Harakiri | ||

| 1963 | Special Jury Prize | Cannes Film Festival | France | |

| 1965 | Kwaidan | |||

| 1967 | Best Film of the Year | Kinema Junpo | Japan | Samurai Rebellion |

| Best Director | ||||

| FIPRESCI Prize | International Federation of Film Critics | |||

| Best Film | Mainichi Film Awards | Japan | ||

| 1975 | Best Film | The Fossil | ||

| 1983 | Best Film | Blue Ribbon Awards | Tokyo Trial | |

| 1984 | Medal with Purple Ribbon (紫綬褒章Shiju HōshōJapanese) | Japanese government | Japan | |

| 1990 | Order of Arts and Letters | French government | France | |

| Order of the Rising Sun (Fourth Class, Gold Rays with Rosette) 勲四等旭日小綬章Kun-yontō Kyokujitsu ShōjushōJapanese | Japanese government | Japan | ||

| 1996 | Special Award | Mainichi Film Awards | ||

| 1996 | Chairman's Special Award | Japan Academy Film Prize | Japan |

8. Personal Life

On April 1, 1952, Masaki Kobayashi married Chiyoko Fumiya, an actress who was also affiliated with Shochiku. Kobayashi maintained a close relationship with his second cousin, the acclaimed actress and director Kinuyo Tanaka. In Tanaka's later years, when she was suffering from cancer and facing financial difficulties, Kobayashi took on the responsibility of caring for her. Tanaka had accumulated significant debt, and her residence was mortgaged. Despite having no legal inheritance rights or rental agreement, Kobayashi tirelessly worked on her behalf, even incurring personal debt to clear the mortgage and cover her hospitalization expenses. Following Tanaka's death, Kobayashi played a crucial role in establishing the Kinuyo Tanaka Award at the Mainichi Film Awards in 1985, an honor bestowed upon actresses who have made significant contributions to Japanese cinema.

9. Death

Masaki Kobayashi passed away on October 4, 1996, at the age of 80, at his home in Setagaya, Tokyo. The cause of his death was a myocardial infarction. His remains are interred in two locations: a portion of his ashes are buried at Engaku-ji, a Buddhist temple in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, and another portion is interred at the Shimonoseki Central Cemetery in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, which is Kinuyo Tanaka's birthplace and the location of her grave.

10. Legacy and Critical Evaluation

Masaki Kobayashi's legacy is that of a master filmmaker whose works profoundly impacted both Japanese and world cinema. Critics widely regard him as one of the finest depicters of Japanese society in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly for his unflinching examination of social injustices, the dehumanizing effects of war, and the resilience of human dignity. His films, characterized by their strong anti-war sentiments and critiques of oppressive systems, continue to resonate for their powerful humanistic themes and artistic integrity.

Posthumous recognition of Kobayashi's contributions has been extensive. On February 14, 2016, to commemorate his 100th birth anniversary and 20th death anniversary, Shochiku, along with the Geiyukai (Kobayashi Masaki Director's Entrusted Business Caretaker Association) and other related companies, launched the "Film Director Masaki Kobayashi 100th Birth Anniversary Project" website. This initiative spurred memorial screenings and special exhibitions across Japan, including a notable "Masaki Kobayashi Exhibition" held at the Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo from July 16 to September 15, 2016. In December 2016, a comprehensive book titled Film Director Masaki Kobayashi (映画監督 小林正樹Eiga Kantoku Kobayashi MasakiJapanese), compiled by Kiyoshi Ogasawara and Hiroko Kajiyama, was published by Iwanami Shoten. This publication features recollections from his acquaintances, interviews with Kobayashi himself, and excerpts from his wartime diaries, offering deeper insights into his life and artistic philosophy. His distinctive vision and unwavering commitment to social commentary ensure his enduring influence on cinematic discourse and filmmaking.