1. Early Life and Background

Marie-Thérèse Louise's early life was shaped by her noble birth within the House of Savoy-Carignano, a cadet branch of the powerful House of Savoy. Her upbringing and education provided the foundation for her later entry into the French royal court and her significant connections within European aristocracy.

1.1. Birth and Childhood

Maria Teresa Luisa was born on 8 September 1749 at the Palazzo Carignano in Turin, then part of the Duchy of Savoy. She was the sixth child and fifth daughter of Louis Victor of Savoy, Prince of Carignano, and Landgravine Christine Henriette of Hesse-Rheinfels-Rotenburg. Her father was a maternal grandson of King Victor Amadeus II of Sardinia and his mistress Jeanne d'Albert de Luynes. Her mother was the sister of Polyxena, the first wife of King Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia. At her birth, it is said that many civilians lined the streets, cheering and singing in celebration. Little is known about the specifics of her childhood.

1.2. Family and Ancestry

Marie-Thérèse Louise's lineage connected her to prominent European royal and noble families. Her father, Louis Victor, Prince of Carignano, was a nephew of King Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia. Her mother, Christine of Hesse-Rotenburg, was related to the French royal family through her sister Caroline, who married Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, a French prince. Her paternal grandparents were Victor Amadeus I, Prince of Carignano and Maria Vittoria of Savoy. Her maternal grandparents were Ernest Leopold, Landgrave of Hesse-Rotenburg and Eleonore of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rochefort. Through these connections, she was descended from several notable European houses, including the House of Hesse and the House of Löwenstein-Wertheim. These connections positioned her well for an advantageous marriage within European aristocracy.

1.3. Education

Details about Marie-Thérèse Louise's specific education are scarce. However, given her aristocratic background, it is presumed she received an education befitting a princess of her standing, likely including instruction in languages, arts, and courtly etiquette, preparing her for a life at a royal court.

2. Marriage and Personal Life

Marie-Thérèse Louise's marriage to the Prince de Lamballe was a pivotal event that brought her into the highest echelons of French society, though it was short-lived. Her subsequent widowhood, substantial inheritance, and charitable endeavors defined her private life and contributed to her public image.

2.1. Marriage to the Prince de Lamballe

On 31 January 1767, Marie-Thérèse was married by proxy in Turin to Louis Alexandre de Bourbon-Penthièvre. He was the son of Louis de Bourbon-Toulouse, Duke of Penthièvre, and Princess Maria Teresa d'Este, making him a grandson of Louis XIV's legitimised son, Louis Alexandre de Bourbon. The marriage was suggested by Louis XV as a suitable match, as both the bride and groom were members of collateral branches of ruling families. The King of Sardinia had long desired an alliance between the House of Savoy and the House of Bourbon, making this union politically advantageous.

The proxy wedding, followed by a bedding ceremony and a banquet, was held at the Savoyard royal court in Turin, attended by the King of Sardinia. On 24 January, the bride crossed the bridge of Beauvoisin between Savoy and France, where she left her Italian entourage and was welcomed by her new French retinue, who escorted her to her groom and father-in-law at the Château de Nangis. She was introduced to the French royal court at the Palace of Versailles in February by Maria Fortunata, Countess de La Marche, where she made a favorable impression. In France, she adopted the French version of her name, Marie Thérèse Louise.

The marriage was initially described as very happy, with both parties attracted to each other's beauty. However, after only a few months, Louis Alexandre was unfaithful with two actresses, which reportedly devastated Marie-Thérèse. She found comfort in her father-in-law, to whom she became very close.

2.2. Widowhood and Inheritance

In 1768, at the age of 19, having been married for just a year, Marie-Thérèse became a widow when her husband died of a venereal disease at the Château de Louveciennes. He was nursed by his spouse and sister in his final illness. Marie-Thérèse inherited her husband's considerable fortune, making her wealthy in her own right. Her father-in-law successfully persuaded her to abandon her wish to become a nun and instead stay with him as his adopted daughter. It is also believed that Marie-Thérèse herself contracted a venereal disease from her husband, which left her unable to conceive children.

2.3. Charitable Activities

Marie-Thérèse comforted her father-in-law in his grief, and joined him in his extensive charitable projects at Rambouillet. This activity earned him the name "King of the Poor" and her the nickname "The Angel of Penthièvre." She lived at the Hôtel de Toulouse in Paris and the Château de Rambouillet, often traveling between the two.

2.4. Proposed Marriage to Louis XV

In 1768, after the death of Marie Leszczyńska, the Queen of France, Madame Marie Adélaïde supported a match between her father and the dowager Princesse de Lamballe, Marie-Thérèse. Madame Adélaïde reportedly preferred a queen who was young and beautiful but lacked ambition, someone who could attract and distract her father from state affairs, leaving them to Madame Adélaïde herself. The match was supported by the Noailles family. However, Marie-Thérèse was not willing to encourage the match herself, and her former father-in-law, the Duke of Penthièvre, was not willing to consent. The marriage plan never materialized, partly due to opposition from the Choiseul faction, who feared a new queen might challenge their political influence.

3. Relationship with Marie Antoinette

The Princesse de Lamballe's life became inextricably linked with that of Marie Antoinette, evolving from a close friendship to a formal court position, enduring shifts in favor, and ultimately demonstrating unwavering loyalty during the tumultuous years of the French Revolution.

3.1. Lady-in-Waiting and Friendship

Marie-Thérèse had a role in royal ceremonies due to her status. When the new Dauphine, Marie Antoinette, arrived in France in 1770, Marie-Thérèse was presented to her along with other "Princes of the Blood" and her father-in-law in Compiégne. During 1771, the Duke de Penthièvre began to entertain more, including the Crown Prince of Sweden and the King of Denmark. Marie-Thérèse acted as his hostess and started to attend court more often, participating in the balls held by Madame de Noailles in Marie Antoinette's name. The Dauphine was reportedly charmed by Marie-Thérèse and overwhelmed her with attention and affection that spectators did not fail to notice. In March 1771, the Austrian ambassador, Mercy, reported: "For some time past the Dauphine has shown a great affection for the Princesse de Lamballe. ... This young princess is sweet and amiable, and enjoying the privileges of a Princess of the Blood Royal, is in a position to avail herself of her Royal Highness's favour."

Marie-Thérèse's presence was noted at high masses and other royal events. In May 1771, she went to Fontainebleau and was presented by the king to her cousin, the future Comtesse de Provence, attending supper afterward. In November 1773, another of her cousins married the third prince, the Count of Artois, and she was present at the birth of Louis-Philippe in Paris in October 1773. As her cousins married Marie Antoinette's brothers-in-law, Marie-Thérèse came to be treated by Marie Antoinette as a relation. During these early years, the Counts and Countesses of Provence and Artois formed a circle of friends with Marie Antoinette and Marie-Thérèse, spending much time together, with Marie-Thérèse described as almost constantly by Marie Antoinette's side. Marie Antoinette's mother, Maria Theresa, somewhat disliked the attachment, as she generally disapproved of favorites and intimate friends of royalty, though Marie-Thérèse's rank made her an acceptable choice if such a friend was deemed necessary.

3.2. Superintendent of the Queen's Household

On 18 September 1775, following Marie Antoinette's ascension to the throne in May 1774, Marie Antoinette appointed Marie-Thérèse "Superintendent of the Queen's Household", the highest rank possible for a lady-in-waiting at Versailles. This appointment was controversial: the office had been vacant for over thirty years because the position was expensive, superfluous, and granted significant power and influence to its holder, giving her rank and authority over all other ladies-in-waiting and requiring all orders given by other female office holders to be confirmed by her. Marie-Thérèse, though of sufficient rank, was regarded as too young, which offended those placed under her. However, the queen viewed it as a just reward for her friend.

After Marie Antoinette became queen, her intimate friendship with Marie-Thérèse received greater attention. Ambassador Mercy reported: "Her Majesty continually sees the Princesse de Lamballe in her rooms [...] This lady joins to much sweetness a very sincere character, far from intrigue and all such worries. The Queen has conceived for some time a real friendship for this young Princess, and the choice is excellent, for although a Piedmontese, Madame de Lamballe is not at all identified with the interests of Mesdames de Provence and d'Artois. All the same, I have taken the precaution to point out to the Queen that her favor and goodness to the Princesse de Lamballe are somewhat excessive, in order to prevent abuse of them from that quarter."

Empress Maria Theresa attempted to discourage the friendship, fearing that Marie-Thérèse, as a former Princess of Savoy, might try to benefit Savoyard interests through the queen. During her first year as queen, Marie Antoinette reportedly told her husband, who approved of the friendship: "Ah, sire, the Princesse de Lamballe's friendship is the charm of my life." Marie-Thérèse welcomed her brothers at court, and at the queen's wish, Marie-Thérèse's favorite brother Eugène was granted a lucrative post with his own regiment in the French Royal Army. Later, Marie-Thérèse also secured the governorship of Poitou for her brother-in-law through the queen's influence.

Marie-Thérèse was described as proud, sensitive, and possessing a delicate, though irregular, beauty. She was not known for her wit or for participating in plots, but she could amuse Marie Antoinette. However, she was reclusive by nature and preferred spending time with the queen alone rather than engaging in high society. She suffered from what was described as "nerves, convulsions, fainting-fits," and reportedly could faint and remain unconscious for hours. The office of Superintendent required her to confirm all orders regarding the queen, channel all letters, petitions, or memoranda to the queen, and entertain on the queen's behalf. This office aroused great envy and insulted many at court due to the precedence in rank it conferred. It also came with an enormous salary of 150.00 K FRF a year. Given the state of the national economy and the princess's great wealth, she was asked to renounce the salary. When she refused for the sake of rank, stating she would either have all the privileges of the office or retire, the queen herself granted her the salary. This incident generated negative publicity, portraying Marie-Thérèse as a greedy royal favorite, and her fainting spells were widely mocked as manipulative simulations. She was openly discussed as the queen's favorite and was greeted almost as visiting royalty when she traveled, with many poems dedicated to her.

3.3. Shifting Favor and Rivalry

In 1775, Marie-Thérèse was gradually replaced in her position as favorite by Yolande de Polastron, the Duchesse de Polignac. The outgoing and social Yolande referred to the reserved Marie-Thérèse as a "boor," while Marie-Thérèse disliked the perceived negative influence Yolande had over the queen. Marie Antoinette, unable to reconcile her two friends, began to prefer Yolande's company, as she could better satisfy her need for amusement and pleasure. In April 1776, Ambassador Mercy reported: "The Princesse de Lamballe loses much in favor. I believe she will always be well treated by the Queen, but she no longer possesses her entire confidence," and continued in May by reporting of "constant quarrels, in which the Princesse seemed always to be in the wrong."

When Marie Antoinette began participating in amateur theater at the Petit Trianon, Yolande persuaded her to refuse Marie-Thérèse's admission to these performances. In 1780, Ambassador Mercy reported: "the Princesse is very little seen at court. The Queen, it is true, visited her on her father's death, but it is the first mark of kindness she has received for long."

3.4. Loyalty and Continued Friendship

Despite being replaced by Yolande as the primary favorite, Marie-Thérèse's friendship with the queen continued on an on-and-off basis. Marie Antoinette occasionally visited her in her rooms and reportedly appreciated her serenity and loyalty amidst the entertainments offered by Yolande, once commenting, "She is the only woman I know who never bears a grudge; neither hatred nor jealousy is to be found in her." After the death of Marie Antoinette's mother, Marie Antoinette isolated herself with Marie-Thérèse and Yolande during the winter to mourn.

Marie-Thérèse retained her office of Superintendent at the French royal court even after losing her position as favorite and continued to perform her duties. She hosted balls in the queen's name, introduced debutantes to her, assisted her in receiving foreign royal guests, and participated in ceremonies surrounding the birth of the queen's children and the queen's annual Easter Communion. Outside of her formal duties, however, she was often absent from court, attending to her own delicate health and that of her father-in-law. She maintained a close friendship with her own favorite lady-in-waiting, Countess Étiennette d'Amblimont de Lâge de Volude, and continued her charitable work and interest in the Freemasons.

3.5. Freemasonry and Health

Marie-Thérèse, along with her sister-in-law, was inducted into the Freemasonic women's Adoption Lodge of St. Jean de la Candeur in 1777, and was made Grand Mistress of the Scottish Lodge in January 1781. Although Marie Antoinette did not become an official member, she was interested in Freemasonry and often inquired of Marie-Thérèse about the Adoption Lodge. During the famous Affair of the Diamond Necklace, Marie-Thérèse was seen in an unsuccessful attempt to visit the imprisoned Jeanne de la Motte at La Salpetriere; the purpose of this visit is unknown, but it created widespread rumors at the time.

Marie-Thérèse had suffered from weak health, which deteriorated significantly during the mid-1780s, often rendering her unable to perform her duties. On one occasion, she even engaged Deslon, a pupil of Franz Mesmer, to mesmerize her. She spent the summer of 1787 in England, advised by doctors to take the English waters in Bath to improve her health. This trip was widely publicized as a secret diplomatic mission on behalf of the queen, with speculations that she was to ask the exiled minister Calonne to omit certain incidents from the memoirs he was about to publish, though Calonne was not in England at that time. After her visit to England, Marie-Thérèse's health improved considerably, allowing her to participate more at court. The queen, whose friendship with Yolande had begun to deteriorate, now showed Marie-Thérèse more affection, appreciating her unwavering loyalty. At this point, Marie-Thérèse and her sister-in-law joined Parliament in petitioning on behalf of the Duke of Orléans, who had been exiled. In the spring of 1789, Marie-Thérèse was present in Versailles to participate in the ceremonies surrounding the opening of the Estates General in France.

By nature, Marie-Thérèse was reserved and had a reputation for being a prude at court. However, in popular anti-monarchist propaganda of the time, she was regularly portrayed in pornographic pamphlets, depicting her as the queen's lesbian lover to undermine the public image of the monarchy.

4. The French Revolution

The French Revolution profoundly impacted Marie-Thérèse Louise's life, transforming her role from a court favorite to a staunch defender of the monarchy, culminating in her ultimate sacrifice.

4.1. Early Revolution and Absence

During the Storming of the Bastille in July 1789 and the outbreak of the French Revolution, Marie-Thérèse was on a leisurely visit to Switzerland with her favorite lady-in-waiting, the Countess de Lâge. When she returned to France in September, she stayed with her father-in-law in the countryside to nurse him while he was ill, and thus was not present at court during the Women's March on Versailles, which took place on 5 October 1789, when she was with her father-in-law in Aumale.

On 7 October 1789, she was informed of the events of the Revolution and immediately joined the royal family in the Tuileries Palace in Paris, where she reassumed the duties of her office. She and Madame Élisabeth shared the apartments of the Pavillon de Flore in the Tuileries Palace, on the same level as the queen's. Except for brief visits to her father-in-law or her villa in Passy, she settled there permanently.

4.2. Role in the Tuileries Palace

In the Tuileries Palace, the ritual court entertainments and representational life were to some extent reinstated. As the king held his levées and couchers, the queen held a card party every Sunday and Tuesday, and held a court reception on Sundays and Thursdays before attending mass and dining in public with the king, as well as giving audience to foreign envoys and official deputations each week. Marie-Thérèse, in her office of Superintendent, participated in all these events, being constantly at the queen's side both in public and private. She accompanied the royal family to St. Cloud in the summer of 1790, and also attended the Fête de la Fédération at the Champ de Mars in Paris in July.

Previously unwilling to entertain in the queen's name as her office required, during these years she entertained lavishly and widely in her apartment at the Tuileries Palace, where she hoped to gather loyal nobles to help the queen's cause. Her salon came to serve as a meeting place for the queen and the members of the National Constituent Assembly, many of whom the queen wished to win over to the cause of the Bourbon monarchy. It was reportedly in Marie-Thérèse's apartment that the queen held her political meetings with Mirabeau.

In parallel, she also investigated the loyalty among the court staff through a network of informers. Madame Campan described how she was once interviewed by Marie-Thérèse, who explained that she had been informed that Madame Campan had been receiving deputies in her room and that her loyalty toward the monarchy had been questioned. However, Marie-Thérèse had investigated the accusations using spies, which had cleared Madame Campan from the charges. Madame Campan wrote, "The Princesse then showed me a list of the names of all those employed about the Queen's chamber, and asked me for information concerning them. Fortunately, I had only favorable information to give, and she wrote down everything I told her."

After the Duchesse de Polignac's departure from France and most others from the queen's intimate circle of friends, Marie Antoinette warned Marie-Thérèse that she would, in her now visible role, attract much of the public's anger toward the queen's favorites, and that libels circulating openly in Paris would expose her to slander. Marie-Thérèse reportedly read one of these volumes and was informed of the hostility voiced toward her.

Marie-Thérèse supported her sister-in-law, the Duchess of Orléans, when she filed for divorce from the Duke of Orléans. This has been viewed as a reason for discord between Marie-Thérèse and the House of Orléans. Although the duke had often used Marie-Thérèse as an intermediary to the queen, he reportedly never quite trusted her, as he expected Marie-Thérèse to blame him for encouraging the behavior that caused the death of Marie-Thérèse's late spouse. When he was informed that she held ill will toward him during this affair, he reportedly broke with her.

4.3. Flight to Varennes and Exile

Marie-Thérèse was not informed beforehand of the Flight to Varennes. On the night of the escape in June 1791, the queen said goodnight to her and advised her to spend some days in the country for her health before she retired. Marie-Thérèse found her behavior odd enough to remark about it to M. de Clermot, before leaving the Tuileries Palace to retire to her villa in Passy. The day after, when the royal family had already departed during the night, she received a note from Marie Antoinette informing her of the flight and instructing her to meet her in Brussels. In the company of her ladies-in-waiting, Countess de Lâge, Countess de Ginestous, and two male courtiers, she immediately visited her father-in-law in Aumale, informed him of her flight, and asked him for letters of introduction.

She departed France from Boulogne to Dover in England, where she stayed for one night before continuing to Ostend in the Austrian Netherlands, arriving on 26 June. She then proceeded to Brussels, where she met Axel von Fersen and the Count and Countess de Provence, and then to Aix-la-Chapelle. She visited King Gustav III of Sweden in Spa for a few days in September, and received him in Aix in October. In Paris, the Chronique de Paris reported her departure, and it was widely believed that she had gone to England for a diplomatic mission on behalf of the queen.

She was long in doubt as to whether she would be of most use to the queen in or outside of France, and received conflicting advice: her friends M. de Clermont and M. de la Vaupalière encouraged her to return to the service of the queen, while her relatives asked her to return to Turin in Savoy. During her stay abroad, she corresponded with Marie Antoinette, who repeatedly asked her not to return to France. However, in October 1791, the new provisions of the Constitution came into operation, and the queen was required to reorganize her household and dismiss all office holders not in service. She accordingly wrote officially to Marie-Thérèse, formally asking her to return to service or resign. This formal letter, though in contrast to the private letters Marie Antoinette had written her, reportedly convinced her that it was her duty to return, and she announced that the queen wished her to return and that "I must live and die with her."

During her stay at a house she had rented in the Royal Crescent in Bath, Great Britain, the princess wrote her will, convinced that she risked mortal danger should she return to Paris. Other information, however, states that the will was made in the Austrian Netherlands, dated "Aix la Chapelle, to-day the 15th October 1791. Marie Thérèse Louise de Savoie". She left Aix-la-Chapelle on 20 October, and her arrival in Paris was announced in the Paris newspapers of 4 November.

4.4. Rallying Support and Public Perception

Back in the Tuileries Palace, Marie-Thérèse resumed her office and her work rallying supporters for the queen, investigating the loyalty of the household, and writing to the noble émigrées, asking them to return to France in the name of the queen. In February 1792, for example, Louis Marie de Lescure was convinced to remain in France rather than emigrating after having met the queen in Marie-Thérèse's apartment, who then informed him and his spouse Victoire de Donnissan de La Rochejaquelein of the queen's wishes that they should remain in France out of loyalty. Marie-Thérèse aroused the dislike of Mayor Pétion, who objected to the queen attending supper in Marie-Thérèse's apartment. Widespread rumors claimed that Marie-Thérèse's rooms at the Tuileries Palace were the meeting place of an 'Austrian Committee' plotting to encourage the invasion of France, a second St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, and the destruction of the Revolution.

During the Demonstration of 20 June 1792, she was present with the queen when a mob broke into the palace. Marie Antoinette immediately cried that her place was by the king's side, but Marie-Thérèse then cried: "No, no, Madame, your place is with your children!" after which a table was pulled before her to protect her from the mob. Marie-Thérèse, alongside Princess de Tarente, Madame de Tourzel, the Duchess de Maillé, Madame de Laroche-Aymon, Marie Angélique de Mackau, Renée Suzanne de Soucy, Madame de Ginestous, and a few noblemen, belonged to the courtiers surrounding the queen and her children for several hours as the mob passed by the room shouting insults to Marie Antoinette. According to a witness, Marie-Thérèse stood leaning by the queen's armchair to support her through the entire scene: "Madame de Lamballe displayed even greater courage. Standing during the whole of that long scene, leaning upon the Queen's chair, she seemed only occupied with the dangers of that unhappy princess without regarding her own."

Marie-Thérèse continued her services to the queen until the attack on the palace on 10 August 1792, when she and Louise-Élisabeth de Croÿ de Tourzel, governess to the royal children, accompanied the royal family when they took refuge in the Legislative Assembly. M. de la Rochefoucauld was present during this occasion and recollected: "I was in the garden, near enough to offer my arm to Madame la Princesse de Lamballe, who was the most dejected and frightened of the party; she took it. [...] Madame la Princesse de Lamballe said to me: 'We shall never return to the Château.'"

During their stay in the clerk's box at the Legislative Assembly, Marie-Thérèse became ill and had to be taken to the Feuillant convent; Marie Antoinette asked her not to return, but she nevertheless chose to return to the family as soon as she felt better. She also accompanied them from the Legislative Assembly to the Feuillant convent, and from there to the Temple.

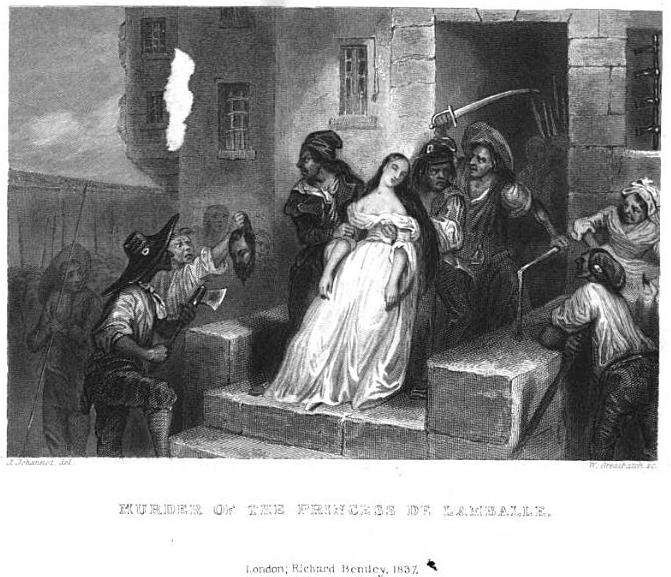

5. Imprisonment and Death

The final chapter of Marie-Thérèse Louise's life was marked by her imprisonment and a brutal death during the September Massacres, a tragic testament to the escalating violence of the French Revolution.

5.1. Arrest and Imprisonment

On 19 August 1792, Marie-Thérèse, Louise-Élisabeth de Croÿ de Tourzel and Pauline de Tourzel were separated from the royal family and transferred to the La Force prison, where they were allowed to share a cell. They were removed from the Temple at the same time as two valets and three female servants, as it was decided that the family should not be allowed to keep their retainers.

5.2. The September Massacres and Trial

During the September Massacres, the prisons were attacked by mobs, and the prisoners were placed before hastily assembled people's tribunals, who judged and executed them summarily. Each prisoner was asked a handful of questions, after which the prisoner was either freed with the words "Vive la nation" ("Long live the nation"), and permitted to leave, or sentenced to death with the words "Conduct him to the Abbaye" or "Let him go," after which the condemned was taken to a yard where they were immediately killed by a mob consisting of men, women, and children. The massacres were opposed by the staff of the prison, who allowed many prisoners to escape, particularly women. Of about two hundred women, only two were ultimately killed in the prison.

Pauline de Tourzel was smuggled out of the prison, but her mother and Marie-Thérèse were too famous to be smuggled out, as their escape would have risked attracting too much notice. Almost all women prisoners tried before the tribunals in the La Force prison were freed from charges. Indeed, not only the former royal governesses Madame de Tourzel and Marie Angélique de Mackau, but also five other women of the royal household: the lady-in-waiting Princess de Tarente, the queen's ladies-maids Marie-Élisabeth Thibault and Bazile, the dauphin's nurse St Brice, Marie-Thérèse's own ladies-maid Navarre, as well as the wife of the king's valet Madame de Septeuil, were all put before the tribunals and freed of charges, as were even two male members of the royal household, the valets of the king and the dauphin, Chamilly and Hue. Marie-Thérèse was therefore somewhat of an exception among those brought before the tribunals.

5.3. Refusal to Swear Oath and Execution

On 3 September 1792, Marie-Thérèse and Madame de Tourzel were taken out to a courtyard with other prisoners, waiting to be taken to the tribunal. She was brought before a hastily assembled tribunal which demanded she "take an oath to love liberty and equality and to swear hatred to the King and the Queen and to the monarchy." She agreed to take the oath to liberty but refused to denounce the king, queen, and monarchy. Her trial was summarily ended with the words "emmenez madame" ("take madame away"). She was in the company of Madame de Tourzel until she was called into the tribunal, and the exact wording of the summary trial is stated to have consisted of the following swift interrogation:

"Who are you?"

"Marie Thérèse Louise, Princess of Savoy."

"Your employment?"

"Superintendent of the Household to the Queen."

"Had you any knowledge of the plots of the court on the 10th August?'"

"I know not whether there were any plots on the 10th August; but I know that I had no knowledge of them."

"Swear to Liberty and Equality, and hatred of the King and Queen."

"Readily to the former; but I cannot to the latter: it is not in my heart."

Reportedly, agents of her father-in-law whispered to her to swear the oath to save her life, upon which she added:

"I have nothing more to say; it is indifferent to me if I die a little earlier or later; I have made the sacrifice of my life."

"Let Madame be set at liberty."

She was then quickly escorted by two guards to the door of the yard where the massacre was taking place; on her way there, the agents of her father-in-law followed and again encouraged her to swear the oath, but she appeared not to hear them. When the door was finally opened and she was exposed to the sight of bloody corpses in the yard, she reportedly cried "Fi horreur!" ("fear be damned") or "I am lost!", and fell back, but was pulled out into the front of the yard by the two guards. Reportedly, the agents of her father-in-law were among the crowd, crying "Grâce! Grâce!" ("Mercy! Mercy!"), but were soon silenced with the shouts of "Death to the disguised lackeys of the Duc de Penthièvre!" One of the killers, who was tried years later, described her as "a little lady dressed in white," standing for a moment alone. Reportedly, she was first struck by a man with a pike on her head, which caused her hair to fall upon her shoulders, revealing a letter from Marie Antoinette which she had hidden in her hair; she was then wounded on the forehead, which caused her to bleed, after which she was stabbed to death by the crowd.

There are many different variations of the exact manner of her death, which attracted great attention and were used in propaganda for many years after the Revolution, during which it was embellished and exaggerated. Some reports, for example, allege that she was raped, and her breasts sliced off in addition to other bodily mutilations. There is, however, nothing to indicate that she was exposed to any sexual mutilations or atrocities, which was widely alleged in the sensationalist stories surrounding her infamous death.

5.4. Treatment of Remains

The treatment of her remains has also been the subject of many conflicting stories. After her death, her corpse was reportedly undressed, eviscerated, and decapitated, with its head placed upon a pike. It is confirmed by several witnesses that her head was paraded through the streets on a pike and her body dragged after by a crowd of people shrieking "La Lamballe! La Lamballe!". This procession was witnessed by a M. de Lamotte, who purchased a strand of her hair which he later gave to her father-in-law, as well as by the brother of Laure Junot.

Some reports say that the head was brought to a nearby café where it was laid in front of the customers, who were asked to drink in celebration of her death. Some reports state that the head was taken to a barber in order to dress the hair to make it instantly recognizable, though this has been contested. Following this, the head was put on the pike again and paraded beneath Marie Antoinette's window at the Temple.

Marie Antoinette and her family were not present in the room outside which the head was displayed at the time and thus did not see it. However, the wife of one of the prison officials, Madame Tison, saw it and screamed, upon which the crowd, hearing a woman scream from inside the Temple, assumed it was Marie Antoinette. Those who were carrying it wished her to kiss the lips of her favorite, as it was a frequent slander that the two had been lovers, but the head was not allowed to be brought into the building. The crowd demanded to be allowed inside the Temple to show the head to Marie Antoinette in person, but the officers of the Temple managed to convince them not to break into the prison. In Antonia Fraser's historical biography, Marie Antoinette: The Journey, Fraser claims Marie Antoinette did not actually see the head of her long-time friend, but was aware of what was occurring, stating, "...the municipal officers had had the decency to close the shutters and the commissioners kept them away from the windows...one of these officers told the king '...they are trying to show you the head of Madame de Lamballe'...Mercifully, the Queen then fainted away."

After this, the head and the corpse were taken by the crowd to the Palais-Royal, where the Duke of Orléans and his lover Marguerite Françoise de Buffon were entertaining a party of Englishmen for supper. The Duke of Orléans reportedly commented "Oh, it is Lamballe's head: I know it by the long hair. Let us sit down to supper," while Buffon cried out "O God! They will carry my head like that someday!"

The agents of her father-in-law, who had been tasked with acquiring her remains and having them temporarily buried until they could be interred in Dreux, reportedly mixed in with the crowd in order to be able to gain possession of it. They averted the intentions of the crowd to display the remains before the home of Marie-Thérèse and her father-in-law at the Hôtel de Toulouse by saying that she had never lived there, but at the Tuileries or the Hôtel Louvois. When the carrier of the head, Charlat, entered an alehouse, leaving the head outside, one agent, Pointel, took the head and had it interred at the cemetery near the Hospital of the Quinze Vingts.

While the procession of the head is not questioned, the reports regarding the treatment of her body have been questioned. Five citizens of the local section in Paris, Hervelin, Quervelle, Pouquet, Ferrie, and Roussel delivered her body (minus her head, which was still being displayed on a pike) to the authorities shortly after her death. Royalist accounts of the incident claimed her body was displayed on the street for a full day, but this is not likely, as the official protocols explicitly state that it was brought to the authorities immediately after her death. While the state of the body is not described, there is, in fact, nothing to indicate that it was disemboweled, or even undressed: the report recounts everything she had in her pockets when she died, and indicates that her headless body was brought fully dressed on a wagon to the authorities the normal way, rather than being dragged disemboweled along the street, as sensationalist stories claimed.

Her body, like that of her brother-in-law Philippe Égalité, was never definitively found.

6. Legacy and Evaluation

The Princesse de Lamballe's legacy is primarily defined by her unwavering loyalty to Marie Antoinette and her tragic death, which made her a poignant symbol of royalist suffering during the French Revolution.

6.1. Historical Significance

Marie-Thérèse Louise's historical significance stems largely from her role as a confidante to Marie Antoinette, particularly during the escalating political crisis of the French Revolution. Her steadfast loyalty, even when the queen's favor shifted, contrasted sharply with the self-preservation instincts of many other courtiers. Her brutal murder during the September Massacres transformed her into a powerful symbol of the monarchy's martyrdom and the extreme violence of the Revolution. She represented the innocent victims caught in the revolutionary fervor, and her death was widely used in anti-revolutionary propaganda to highlight the barbarity of the revolutionaries.

6.2. Positive Contributions

Beyond her personal connection to the queen, Marie-Thérèse Louise is remembered for her extensive charitable work, particularly alongside her father-in-law, the Duke of Penthièvre. Her philanthropic efforts earned her the affectionate nickname "The Angel of Penthièvre," showcasing a compassionate side that stood in contrast to the perceived extravagance of the court. Her personal loyalty to Marie Antoinette, especially in the face of danger, is also highlighted as an enduring positive aspect of her character, often seen as a rare virtue in the turbulent political climate of her era.

6.3. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite her positive attributes, Marie-Thérèse Louise also faced criticisms and controversies. Her appointment as Superintendent of the Queen's Household was met with resentment due to its high cost and the extensive power it conferred, especially given the precarious state of the national finances. Her refusal to renounce her substantial salary further fueled public perception of her as a greedy royal favorite. In anti-monarchist propaganda, she was frequently targeted and portrayed in scandalous ways, including as the queen's lesbian lover, as part of a deliberate effort to undermine the monarchy's public image. These portrayals, though largely unfounded, contributed to the widespread hostility directed towards her and other figures associated with the royal family.

6.4. Cultural Influence

The Princesse de Lamballe left a mark on cultural history beyond her direct involvement in court life. From 1770 to 1780, she commissioned the creation of an English-style garden hamlet, La Chaumière aux Coquillages (The Shell Cottage), at Rambouillet. This charming structure was greatly admired by Queen Marie Antoinette and served as a model for her own Queen's Hamlet at the Petit Trianon. In 1780, the composer and harpist Jan Křtitel Krumpholtz dedicated his Sonata for Harp, Op. 8 to her.

6.5. Portrayals in Media

The Princesse de Lamballe has been portrayed in several films and miniseries, reflecting her enduring presence in historical narratives and popular culture.

- Anita Louise in W. S. Van Dyke's 1938 film Marie Antoinette.

- Mary Nighy in the 2006 film Marie Antoinette, directed by Sofia Coppola.

- Gabrielle Lazure in the 1989 miniseries La Révolution française.

- Jasmine Blackborow in the television series Marie Antoinette, which began airing in 2022.

- She is also mentioned in the 1905 children's book A Little Princess, where the main character, Sara, is fascinated with the French Revolution and recounts the Princess's death to her friend.

- The Princesse de Lamballe is also a character in the Japanese manga I Was Reincarnated as the Villainess in an Otome Game but I Became Marie Antoinette by Yoshito Koide.

- According to Madame Tussaud, she was ordered to make a death mask of the Princesse de Lamballe.