1. Early Life and Family

Marguerite Louise d'Orléans was born on July 28, 1645, at the Château de Blois, though some sources also indicate the Louvre Palace as her birthplace. She was the eldest child born to Gaston of France, Duke of Orléans, and his second wife, Marguerite of Lorraine. She was the eldest of five children from Gaston's second marriage. Her sisters included Élisabeth Marguerite d'Orléans, who would become the Duchess of Guise, and Françoise Madeleine d'Orléans, who later married Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Marguerite Louise received a rudimentary education at her father's court in Blois, where he had retreated following the failed insurrection against his nephew Louis XIV known as the Fronde. She developed a particularly close relationship with her influential half-sister, Anne Marie Louise, Duchess of Montpensier, famously known as La Grande Mademoiselle. Her half-sister frequently took Marguerite Louise and her friends to the theatre and royal balls. Marguerite Louise reciprocated this affection, attending Anne Marie Louise's salon daily and seeking her guidance on court matters.

Marguerite Louise was convinced that Madame de Choisy had poorly advised her mother, leading to the failure of negotiations for her marriage to Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy. Ultimately, it was her younger sister, Françoise Madeleine d'Orléans, who married Charles Emmanuel in 1663. Despite this, when a new marriage proposal emerged in 1658 from Cosimo de' Medici, the Grand Prince of Tuscany, Marguerite Louise asked her half-sister to facilitate the match. Initially, she was overjoyed at the prospect of marriage, but her enthusiasm turned to dismay when her half-sister, who had initially favored the Tuscan match, changed her mind. In response, Marguerite Louise's behavior became increasingly unconventional. She shocked the court by going out unaccompanied, a serious offense in contemporary French society, with her cousin Prince Charles of Lorraine, who soon became her lover.

2. Marriage and Life in Tuscany

The circumstances surrounding Marguerite Louise's marriage to Cosimo III de' Medici were complex, marked by diplomatic maneuvering and her own defiant personality. Her arrival in Tuscany and subsequent life as Grand Princess and later Grand Duchess were characterized by deep personal struggles and conflicts within the rigid structure of the Medici court.

2.1. Engagement and Marriage

The engagement between Marguerite Louise and Cosimo de' Medici was first orchestrated by Cardinal Mazarin in 1652. Despite her ongoing affair with Charles of Lorraine, the marriage negotiations proceeded. The proxy marriage took place on April 19, 1661. However, this formal commitment did little to alter her rebellious attitude, much to the annoyance of Louis XIV's ministers. On the very day she was expected to receive diplomats offering their congratulations on the wedding, she attempted instead to go hunting, only to be stopped by the Duchess of Montpensier.

Mattias de' Medici, the brother of the reigning Grand Duke Ferdinando II and her bridegroom's uncle, was tasked with conveying Marguerite Louise to Tuscany. He did so in a fleet of nine galleys, three from Tuscany, three loaned from the Republic of Genoa, and another three from the Papal States. Breaking all protocol, Charles of Lorraine saw her off at Marseille. The party arrived in Tuscany on June 12, with the bride disembarking at Livorno. She made her formal entry into Florence on June 20, amidst much pageantry. Their wedding celebrations were the most lavish spectacle Florence had ever witnessed, featuring a cortège of over 300 carriages. As a wedding gift, Grand Duke Ferdinando presented her with a pearl described as the "size of a small pigeon's egg."

2.2. Grand Princess and Grand Duchess

Marguerite Louise and Cosimo greeted each other with indifference. According to Sophia, Electress of Hanover, they only slept together once a week. Just two days after their marriage, Marguerite Louise demanded possession of the Tuscan crown jewels from Cosimo, who replied that he lacked the authority to grant them. The jewels she did manage to acquire from Cosimo, she attempted to smuggle out of Tuscany, only to be intercepted by the Grand Duke. Following this incident, Marguerite Louise's indifference intensified into outright hatred, a sentiment compounded by her enduring love for Charles of Lorraine, from whom she had been forcibly separated at Marseille. On one occasion, her defiance escalated to the point where she threatened to break a bottle over Cosimo's head if he did not leave her chamber.

Her deep animosity towards Cosimo, however, did not prevent them from fulfilling their dynastic duty to produce heirs. They had three children: Grand Prince Ferdinando in 1663, Anna Maria Luisa in 1667, and Gian Gastone in 1671.

2.3. Relationship with Cosimo III and Family Conflicts

Marguerite Louise's unconventional behavior led to consistently strained relations within the Medici family. She frequently argued with her mother-in-law, Grand Duchess Vittoria, over matters of precedence, and with Grand Duke Ferdinando over her excessive spending habits. Her financial extravagance not only caused conflict with the Grand Duke but also made her unpopular with the Florentines. This unpopularity was exacerbated by her free-spirited conduct, such as allowing two grooms to frequent her chamber at all hours. Her husband, Cosimo III, was known for his ascetic and devout nature, often disliking physical relations, which further contributed to their incompatibility. The Florentine court felt stifling and boring to Marguerite Louise, who was accustomed to the vibrant French court. Her father-in-law, Ferdinando II de' Medici, went so far as to expel her French retinue and exert considerable pressure on her to fulfill her most crucial duty: producing an heir for the Grand Duchy. Marguerite Louise often refused to sleep with Cosimo and, upon discovering her pregnancies, even attempted to induce miscarriages. Louis XIV himself had to intervene, urging her to behave appropriately. Cosimo III, in an effort to improve their marital relations, took several trips abroad, believing that temporary separation might help.

2.4. Pleas to Louis XIV and French Intervention

Following a brief visit by Charles of Lorraine to Florence, during which he was entertained by the Grand Ducal family at the Palazzo Pitti, the tone of Marguerite Louise's letters to Charles prompted Grand Duke Ferdinando II and Cosimo to begin spying on her. In response, she unsuccessfully appealed to Louis XIV to intervene on her behalf. However, both Marguerite Louise and the Grand Duke later sent entreaties to Louis XIV after her French staff was dismissed; Marguerite Louise complained of mistreatment, while the Grand Duke sought assistance in restraining her behavior.

To appease both parties, Louis XIV dispatched the Comte de Saint Mesme. During their conversations, it became clear that Marguerite Louise desperately wished to return to France. Mesme, along with much of the French court, sympathized with her desire, and he concluded his visit without finding a solution to the heir's domestic problems, which angered both Ferdinando and Louis XIV. Subsequently, Marguerite Louise began to force the issue by humiliating Cosimo at every possible opportunity. For instance, she insisted on employing only French cooks, claiming the Medici family intended to poison her, and publicly branded Cosimo "a poor groom" in front of the Papal nuncio.

After several more French attempts at conciliation failed, in September 1664, Marguerite Louise abandoned her apartment in the Palazzo Pitti, refusing to return. As a consequence, Cosimo moved her to Villa di Lappeggi, where she was placed under constant surveillance by 40 soldiers, and six courtiers appointed by Cosimo were required to follow her everywhere, due to fears that she would flee to France. The following year, she changed her approach and reconciled with the Grand Ducal family. However, this particular reconciliation collapsed after the birth of Anna Maria Luisa in 1667.

In May 1670, with the death of Grand Duke Ferdinando II, Marguerite Louise officially became the Grand Duchess of Tuscany. The ancient tradition of admitting the reigning Grand Duke's mother to the Consulta, or Privy Council, was reinstated upon Cosimo III's accession. Grand Duchess Vittoria, who loathed Marguerite Louise for her treatment of Cosimo and herself, ensured that Marguerite Louise was denied membership in the Consulta. Effectively excluded from political influence, Marguerite Louise was left with little to do but supervise the education of her son, Grand Prince Ferdinando. Furious at her exclusion, the Grand Duchess clashed with Vittoria over precedence and vehemently demanded entry to the Consulta. Cosimo III consistently sided with his mother in these disputes. Although a brief reconciliation likely occurred in the summer of 1670, evidenced by the birth of their last child, Gian Gastone, on May 24, 1671, by early 1671, the fighting between Marguerite Louise and Vittoria had become so intense that a contemporary observer remarked that "the Pitti Palace has become the devil's own abode, and from morn till midnight only the noise of wrangling and abuse can be heard." The birth of Gian Gastone on the first anniversary of his grandfather Ferdinando II's death provided an occasion for the child to receive the name of his other, maternal grandfather, Gaston, Duke of Orléans, who had died in 1660. Gian Gastone would later become the last Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany.

3. Children

Cosimo III and Marguerite Louise had three children, none of whom produced legitimate issue, leading to the eventual extinction of the main Medici line:

- Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany (1663-1713). He married Duchess Violante Beatrice of Bavaria but had no children.

- Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici, Electress Palatine (1667-1743). She married Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine but had no children.

- Gian Gastone de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1671-1737). He married Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg but had no children.

4. Return to France and Life in Convents

Marguerite Louise's tumultuous life in Tuscany eventually led to her departure and a new chapter in France, primarily within religious communities, where she continued to navigate societal expectations and pursue personal autonomy.

At the start of 1672, Marguerite Louise wrote to Louis XIV, pleading for medical assistance for what she described as breast cancer. In response, Louis XIV dispatched Alliot le Vieux, the personal physician who had attended his own mother, Anne of Austria, who had died from the same ailment. Alliot, unlike Saint Mesme, did not fully comply with Marguerite Louise's desire to be sent to France on the pretext of illness, declaring that the tumor was "in no wise malignant," though he did recommend thermal waters. Frustrated by the failure of her plan, Marguerite Louise began flirting with a cook in her household, engaging in playful acts like tickling and pillow fights, specifically to upset Cosimo.

In an effort to restore domestic harmony, Cosimo III sent for Madame du Deffand, Marguerite Louise's childhood governess who had previously sided with the Grand Duke. However, due to a series of deaths in the Orléans family, the governess's arrival was delayed until December 1672. By then, Marguerite Louise was in deep despair and requested permission to visit Villa Poggio a Caiano, a Medici villa, ostensibly for worship at a nearby shrine. Once there, she refused to return, initiating a two-year standoff with the Grand Duke, who would not consent to her return to France, despite her pleas in a parting letter to him. Madame du Deffand's mission having failed, Louis XIV made one final, unsuccessful attempt to reconcile the Grand Ducal couple.

With all attempts at conciliation having failed, Cosimo finally capitulated to Marguerite Louise's demands in a contract signed on December 26, 1674. The agreement stipulated that Marguerite Louise would receive a pension of 80.00 K FRF and be permitted to return to France, but she had to confine herself to the Abbey of Saint Peter at Montmartre and surrender her rights as a Royal Princess of France. Overjoyed, the Grand Duchess departed for France on June 12, 1675, laden with the fixtures and furniture from Villa Poggio a Caiano, declaring that she had no intention "of setting forth without her proper wages."

4.1. Residence at Montmartre

News of Marguerite Louise's departure from Livorno on July 12, 1675, was met with "a great displeasure" by the Florentines. The nobility, too, largely sympathized with her, believing Cosimo to be responsible for driving her away.

Upon her arrival at Montmartre, Marguerite Louise initially patronized charitable works and maintained "an air of piety." However, she soon reverted to her unconventional ways, wearing heavy rouge and bright yellow periwigs, and embarking on affairs, first with the Count of Lovigny, and later with two members of the Luxembourg regiment. Louis XIV, disregarding the 1674 contract's article that prohibited Marguerite Louise from leaving the convent, admitted the Grand Duchess to court, where she gambled for high stakes. Due to her "shabby" retinue and brief visits, Marguerite Louise gained a reputation as a Bohemian among the courtiers of Versailles, which compelled her to allow "those of insignificant birth" into her social circle. The Tuscan envoy, Gondi, frequently protested Marguerite Louise's behavior to the French court, but to no avail. Eventually, the Abbess of Montmartre, Françoise Renée de Lorraine (1621-1682), when questioned by the King about Marguerite Louise's latest affair with a groom, famously replied, "A conspiracy of silence is the sole antidote to the depravity and excesses of [Marguerite Louise]." This sentiment perhaps explains her notable absence from the memoirs of that era.

Back in Florence, Cosimo III meticulously scrutinized the reports sent by the Tuscan envoy in France regarding Marguerite Louise's every movement. If he deemed a particular action offensive, he would write to Louis XIV, demanding an explanation. Although initially sympathetic to Cosimo, Louis XIV eventually grew weary of his endless stream of protests, stating, "Since Cosimo had consented to the retirement of his wife to France, he had virtually relinquished any right to interfere in her conduct." This declaration prompted Cosimo III to cease concerning himself with his wife's behavior. Marguerite Louise was informed of Cosimo III's ensuing illness by her eldest son, Grand Prince Ferdinando, who had openly espoused his mother's cause and corresponded with her. Convinced of her husband's imminent death, Marguerite Louise reportedly told the French court that "at the first notice of her detested husband's demise, she would fly to Florence to banish all hypocrites and hypocrisy and establish a new government." However, this was not to be, as Cosimo III actually outlived her by two years.

In 1688, burdened by debts, Marguerite Louise wrote to Cosimo, begging for 20.00 K GBP. When Cosimo was not initially forthcoming, she shifted her focus to her son, the Grand Prince, hoping he would help her, but he feigned inability, fearing his father's displeasure. Eventually, Cosimo settled her debts, and her financial security was further assured when she inherited a substantial sum of money from a relative in 1696. While Marguerite Louise's behavior had been tolerated by the previous Abbess of Montmartre, the new Abbess, Madame d'Harcourt, frequently complained about her to both the Grand Duke and the King. In retaliation, Marguerite Louise threatened to kill the Abbess with a hatchet and a pistol, and formed a clique against her. It was in this context that Cosimo III consented, in line with her wishes, to Marguerite Louise's departure for a new convent at Saint-Mandé on the eastern outskirts of Paris. This move was contingent on her only going out with Louis XIV's explicit permission and being attended by a chamberlain of his choice. Since she initially refused to agree to these terms, her pension was suspended, only to be resumed when Louis XIV compelled her to yield.

4.2. Residence at Saint-Mandé

At Saint-Mandé, the aging Marguerite Louise adopted a more moderate lifestyle and dedicated herself to reforming the convent, which she controversially described as a "spiritual brothel." She ensured the absentee mother superior, who was known to wear men's clothing, was sent away, and nuns who deviated from the established rule were removed. Through these efforts, Marguerite Louise's behavior ceased to be a point of contention with Florence.

Marguerite Louise's health began to decline in 1712, marked by an attack of apoplexy that left her with a paralyzed left arm and foaming at the mouth. She recovered, but suffered another attack the following year. The death of her eldest son, Grand Prince Ferdinando, the only one of her three children with whom she had a good relationship, contributed significantly to this second stroke, which briefly paralyzed her eyes and made speech difficult. The Regent of France, Philippe d'Orléans, allowed Marguerite Louise to purchase a house in Paris at 15 Place des Vosges, where she spent her final years. During this period, she corresponded with the Regent's mother, Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, and diligently engaged in charitable activities.

5. Later Life and Death

Marguerite Louise d'Orléans spent her final years in her house at 15 Place des Vosges in Paris, where she continued to dispense charity and maintain dignified correspondence. Despite earlier health setbacks, including two attacks of apoplexy, she remained active in her charitable endeavors. Her life, marked by early defiance and later a shift towards more conventional and pious behavior, came to an end. Marguerite Louise d'Orléans, Princess of France and Grand Duchess of Tuscany, died on September 17, 1721. She was buried in the Picpus Cemetery in Paris.

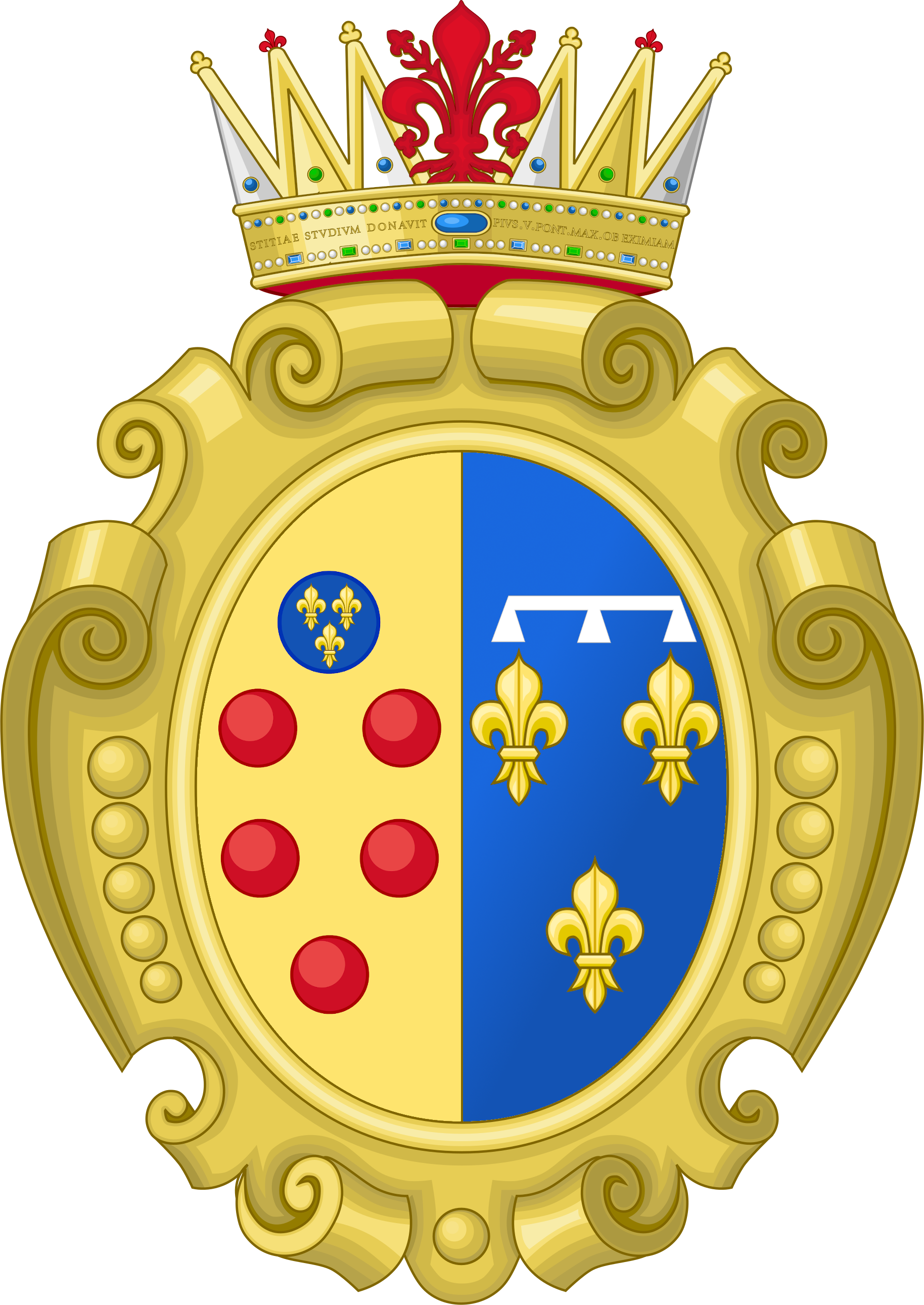

6. Ancestry

Marguerite Louise d'Orléans's ancestry reflects her extensive connections to prominent European royal houses, underscoring her dynastic significance. Her lineage can be traced back through several generations of French, Lorraine, and Medici royalty.

| Generation 8 | Generation 7 | Generation 6 | Generation 5 | Generation 4 | Generation 3 | Generation 2 | Generation 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Marguerite Louise d'Orléans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Gaston, Duke of Orléans | 3. Marguerite of Lorraine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Henry IV of France | 5. Marie de' Medici | 6. Francis II, Duke of Lorraine | 7. Christina of Salm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Antoine of Navarre | 9. Jeanne III of Navarre | 10. Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany | 11. Joanna of Austria | 12. Charles III, Duke of Lorraine | 13. Claude of Valois | 14. Paul, Count of Salm-Brandenburg | 15. Marie Le Veneur de Tillières | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. Charles, Duke of Vendôme | 17. Françoise of Alençon | 18. Henry II of Navarre | 19. Marguerite of Angoulême | 20. Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany | 21. Eleanor of Toledo | 22. Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor | 23. Anne of Bohemia and Hungary | 24. Francis I, Duke of Lorraine | 25. Christina of Denmark | 26. Henry II of France | 27. Catherine de' Medici | 28. John VII, Count of Salm-Badenweiler | 29. Louise de Stainville | 30. Tanneguy Le Veneur, Comte de Tillières | 31. Madeleine Hélie de Pompadour |