1. Overview

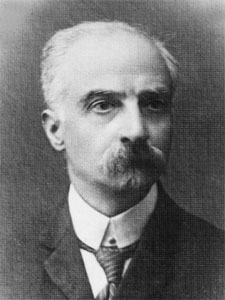

Luigi Galleani was a prominent Italian insurrectionary anarchist known for his fervent advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", a controversial strategy that promoted the use of violence, including assassinations and bombings, to dismantle existing governmental and capitalist structures. Born in Vercelli, Italy, Galleani became a leading voice in the Piedmont labor movement before facing arrest and exile. He immigrated to the United States in 1901, where he significantly influenced the Italian immigrant workers' movement, particularly through his radical newspaper Cronaca Sovversiva. His followers, known as the Galleanisti, embraced his anti-organizational and insurrectionary principles, carrying out a series of high-profile bombing attacks across the United States. Galleani's anti-war activism during World War I led to his deportation back to Italy in 1919. There, he faced severe political repression under the rising Fascist regime until his death in 1931. His ideology centered on the belief that social change could only be achieved through continuous, violent attacks against institutions, rejecting formal organization and reformist approaches, and justifying actions such as assassination as necessary for social transformation.

2. Biography

Luigi Galleani's life was marked by relentless activism, intellectual pursuit, and repeated confrontations with authorities, from his early days in Italy to his influential period in the United States and his final years under Fascist rule.

2.1. Early life and activities in Italy

Luigi Galleani was born on August 12, 1861, into a middle-class family in the Piedmontese city of Vercelli, Italy. His interest in anarchism began during his law studies at the University of Turin, leading him to abandon a legal career to dedicate himself to anarchist propaganda against capitalism and the state. His exceptional skills in oratory and writing quickly established him as a leading figure in the burgeoning Italian anarchist movement. Alongside Sicilian anarchist Pietro Gori, Galleani spearheaded a resurgence of militant anarchist activism, garnering significant support among workers in Northern Italy.

By the mid-1880s, anarchists had lost ground to the Italian Workers' Party (POI), which had built a large base among northern workers. Initially skeptical of the POI's leanings towards workerism and reformism, Galleani nonetheless led the Piedmontese anarchist movement's reorientation towards the labor movement and a rapprochement with the POI in 1887. That year, he founded the Turin-based newspaper Gazzetta Operaia, established several workers' organizations in Vercelli, and distributed revolutionary propaganda among factory workers in Biella. In 1888, he undertook a lecture tour across Piedmont and led a series of strike actions by Piedmontese workers in both Turin and Vercelli, thereby increasing support for both the anarchist movement and the POI.

Despite Galleani's efforts to infiltrate the POI and steer it towards revolutionary socialism, relations between anarchists and the POI deteriorated due to the latter's continued participation in local elections. While he advocated for conciliation, preventing a formal split, the two factions remained irreconcilable, and Galleani's attempts to transform the POI ultimately failed.

Threatened with arrest for his radical activism, Galleani fled to France in 1889, then to Switzerland. There, he collaborated with the French anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus on his Nouvelle Géographie Universelle and organized a student demonstration at the University of Geneva in honor of the Haymarket martyrs. While en route to the Italian anarchist movement's Capolago congress, he was arrested by Swiss authorities and expelled back to Italy. Upon his return, he immediately resumed his radical activities, embarking on a speaking tour in Tuscany with the aim of fomenting an uprising on International Workers' Day in 1891.

In 1892, Galleani, along with Pietro Gori and Calabrese anarchist Giovanni Domanico, represented anarchists at the Genoa Workers' Congress. Their intention was to obstruct the motions of the dominant reformist faction, led by social democrat Filippo Turati. An alliance formed between anarchists and workerists, both opposing political participation. On August 14, a fierce argument erupted between anarchist and socialist delegates, leading to two separate meetings the following day. Turati's social democratic majority ultimately forced the anarchists to split from the movement, establishing the new Italian Socialist Party (PSI). Galleani's attempts to form an anarchist party were unsuccessful, and the congress demonstrated that his agitational campaign had failed to gain mass support among workers, leading many Italian anarchists to become disillusioned with the labor movement, which was now under the direction of the PSI.

In the wake of the Fatti di Maggio (Bava Beccaris massacre), the Italian government launched a new campaign of political repression against the anarchist movement, arresting anarchists en masse and exiling them without trial to small islands for up to five years. Galleani was swiftly arrested, convicted of conspiracy, and exiled to the Sicilian island of Pantelleria in 1894, where he served five years. On Pantelleria, he met and married Maria Rallo, who already had a young son. Luigi and Maria Galleani subsequently had four more children.

With the aid of Élisée Reclus, Galleani managed to escape from Italy to Egypt in 1900, where he stayed with other Italian exiles for several months. Facing the threat of extradition back to Italy by Egyptian authorities, he fled to London by ship, and from there, immigrated to the United States, arriving in October 1901, shortly after the assassination of William McKinley, the United States President.

2.2. Immigration to the United States and early activities

Upon his arrival in the United States at the age of 40, Galleani quickly gained attention within radical anarchist circles as a charismatic orator. He settled in Paterson, New Jersey, a significant hub for Piedmontese immigrant silk weavers and dyers, and became the editor of La Questione SocialeThe Social QuestionItalian, then the most important Italian anarchist publication in the United States. Galleani passionately advocated for the necessity of violence to overthrow the capitalist system that he believed oppressed the working class. He proudly described himself as a destructive and revolutionary propagandist dedicated to the annihilation of government, possessing a remarkable talent for appealing to revolutionary violence.

In 1902, during a silk workers' strike in Paterson, Galleani became a vocal supporter of the laborers, urging them to initiate a general strike to overthrow American capitalism. During clashes between the striking workers and police, he was shot in the face and subsequently charged with incitement to riot. Galleani escaped to Canada but was arrested there and deported back to the United States. He then went into hiding in Barre, Vermont, where he found refuge among Tuscan stonemasons from Carrara, who formed a significant part of Barre's socialist and anarchist communities.

2.3. Press activities and propagation of thought in the United States

In Barre, Galleani resumed delivering fiery speeches and writing extensively. On June 6, 1903, with his new comrades, he launched Cronaca Sovversiva (Cronaca SovversivaSubversive ChronicleItalian), which rapidly became the most influential Italian anarchist periodical in North America, distributed worldwide. Galleani continued to publish this anarchist newspaper for 15 years until the U.S. government suppressed it under the Sedition Act of 1918. Each issue of Cronaca Sovversiva typically comprised eight pages and reached approximately 5,000 subscribers at its peak. The newspaper expressed radical views on various subjects, including atheism, free love, critiques of modern and historical state tyranny, and strong condemnations of overly passive socialists. It often included lists of addresses and personal information of individuals deemed "enemies of the people," such as businessmen, "capitalist spies," and "strike-breakers." Books published under Galleani's name, such as La Fine dell'Anarchismo?The End of Anarchism?Italian, were often compilations of essays originally featured in Cronaca Sovversiva.

Through Cronaca Sovversiva, Galleani articulated his theories of direct action and armed resistance against the state. He lauded the actions of anarchist assassins, including Gaetano Bresci, an anarchist from Paterson, New Jersey, who traveled to Italy to assassinate Umberto I of Italy. A posthumously published collection of his writings from Cronaca Sovversiva was titled Aneliti e Singulti: MedaglioniGasps and Sobs: MedallionsItalian.

In 1905, Cronaca Sovversiva advertised a 25-cent pamphlet titled La Salute è in voi!Health is in You!Italian, described as a "must-have item for every proletarian household." The preface of this manual, first published in 1905, stated its purpose was to rectify the error of advocating violence without providing practical means for destructive physical action. La Salute è in voi! was explicitly a bomb-making manual, including a formula for manufacturing nitroglycerine, compiled by Galleani's friend and explosives expert, Professor Ettore Molinari. While the manual was later classified by the New York bomb squad as accurate and practical, Galleani's initial transcription contained errors that led to premature explosions. He issued a warning and a corrected text to readers in a 1908 issue of Cronaca Sovversiva. In 1914, Galleani published Faccia a Faccia col NemicoFace to Face with the EnemyItalian, in which he praised anarchist assassins as martyrs and revolutionary heroes.

In late 1907, Galleani published a series of articles defending anarchism in response to Neapolitan socialist Francesco Saverio Merlino's public renunciation of anarchism in favor of reformist labor unionism. By this time, Galleani had become disillusioned with the labor movement and came to reject labor unions entirely, adopting an anti-organizational form of anarchism that became the dominant tendency within the Italian American anarchist movement. He even openly broke with the anarcho-syndicalist Carlo Tresca over Tresca's cooperation with the Industrial Workers of the World, causing a rift among their followers that undermined the cohesion of the Italian American anarchist movement.

Galleani attracted many militant and deeply devoted followers, known as the Galleanisti. These disciples, including Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, likewise rejected all formal organization and developed markedly extremist tendencies. They promoted Galleani's lectures and distributed his literature. Following Galleani's anti-organizational principles, the Galleanisti formed small, tight-knit cells of "self-selecting individuals." While they formally rejected leadership, Galleani himself was treated with reverence and held the status of an unofficial leader. The fact that Sacco and Vanzetti were Galleanists and subscribers to Cronaca Sovversiva was later used by judicial authorities to target them.

2.4. Deportation and later years in Italy

Following the American entry into World War I, Galleani became a leading voice in the anti-war movement, declaring that the anarchist movement was "Against the War, Against the Peace, For Social Revolution!" In response to the passage of the Selective Service Act of 1917, he urged his followers to refuse registration and go into hiding. He and many of his comrades moved to a cabin in the woods near Taunton, Massachusetts. At his direction, some Galleanisti escaped to Mexico, from where they planned to return to Italy, believing a revolution was imminent. Despite the ongoing Mexican Revolution, Galleani had rejected the possibility of an anarchist revolution in Mexico itself, characterizing its high population of people of color as "uninterested" racial groups, reflecting his racism.

His anti-war activities made him a target for political repression by the American government. On June 17, 1917, federal agents raided the offices of Cronaca Sovversiva in Lynn, Massachusetts, arresting Galleani and shutting down the newspaper. Charged with conspiracy, he and eight of his followers were subsequently deported back to Italy on June 24, 1919, leaving his family behind in the United States. Although his deportation occurred three weeks after a series of Galleanist bombings, it was primarily due to authorities classifying him as a foreign agitator who incited violent uprisings against the government.

Upon his arrival in Turin, Italy, Galleani attempted to continue publishing Cronaca Sovversiva, but it was quickly suppressed by the Italian authorities. Following the March on Rome in 1922 and the rise of Italian Fascism, he was arrested and convicted of sedition by the new Fascist authorities, receiving a 14-month prison sentence. After his release, he concluded his polemic against Merlino, writing a further series of articles and publishing them together in his book The End of Anarchism? (1925). While the book was hailed by Neapolitan anarchist Errico Malatesta as a key text in anarchist communism, its publication provoked Galleani's arrest by Fascist authorities in November 1926, on charges of insulting the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Galleani was imprisoned for six months, spending time in the same cell he had been kept in during 1892, before being banished to Lipari and later Messina.

In February 1930, Galleani was granted compassionate release due to his failing health. He retired to CaprigliolaCaprigliolaItalian, a 'frazione' of Aulla, where he was kept under close and constant surveillance by the police. After returning from a walk through the countryside, during which he was followed by the police, he collapsed from a heart attack, dying on November 4, 1931, at the age of 70.

3. Political Ideology

Luigi Galleani's political ideology was a radical form of anarchist communism that vehemently rejected traditional political structures and advocated for direct, violent action as the sole path to social liberation.

3.1. Insurrectionary Anarchism and Propaganda of the Deed

Galleani's conception of anarchist communism synthesized the insurrectionary anarchism expounded by German individualist Max Stirner with the concept of mutual aid advocated by Russian communist Peter Kropotkin. He staunchly defended the principles of revolutionary spontaneity, autonomy, diversity, self-determination, and direct action. At the core of his philosophy was the advocacy for the violent overthrow of the state and capitalism through "propaganda of the deed". This strategy involved direct, often violent, actions against the state and capitalist systems, which he believed would serve as a catalyst for a broader popular insurrection. For Galleani, propaganda of the deed manifested as the assassination of authority figures and the expropriation of private property. He openly endorsed terrorism as a legitimate means to achieve social change. He notably defended the assassinations of U.S. President William McKinley by Leon Czolgosz and of Umberto I of Italy by Gaetano Bresci.

3.2. Rejection of Organization and Critique of Reformism

Galleani fundamentally rejected all forms of formal organization, including anarchist federations and labor unions. He opposed participation in the labor movement, believing it was inherently reformist and susceptible to corruption. From his rejection of reformism, he concluded that genuine social change could only be brought about through violent attacks against institutions, which he believed would build towards a popular uprising. He had undisguised contempt for those who refused to participate in the violent overthrow of capitalism. His anti-organizational stance became a dominant tendency within the Italian American anarchist movement, leading to a rift with figures like Carlo Tresca who cooperated with organizations like the Industrial Workers of the World.

3.3. Views on Revolution and Violence

Galleani justified and actively advocated for violence, assassination, and bombings as essential methods for social transformation. He believed that such actions were necessary to dismantle the oppressive structures of the state and capitalism. His ultimate aim was to establish "a society without masters, without government, without law, without any coercive control-a society functioning on the basis of mutual agreement and allowing each member the freedom to enjoy absolute autonomy."

The following excerpt from a leaflet found at the scene of a series of bombings by Galleani's followers, titled "Plain Words," exemplifies their justification for violence and their perspective on class war:

:Power here in America makes no secret of its will to stop the spread of the revolution that is now spreading throughout the world. So let Power accept the fight they have provoked.

:The time has come when the solution to social problems can no longer be delayed, and the class war will not end without the complete victory of the international proletariat. This challenge is an old one... You, the "democratic" monarchs of the dictatorial republic. When we dreamed of liberation, when we spoke of freedom, when we yearned for a better world, you have imprisoned, beaten, exiled, and killed us... whenever you could!

:Now that your war to fill your wallets and build your pedestals of saints is over, the best way to protect your accumulated wealth and wicked reputation will be to suppress the workers' pursuit of a better life with the murderous institutions created to protect your privileges.

:The prisons built to bury every voice of protest are now filled with conscious workers whose health is failing, yet you are not satisfied and increase their numbers daily.

:It was yesterday's history that your gunmen indiscriminately shot unarmed masses, but under your rule, this has become daily history, and now all prospects have worsened.

:Do not expect us to sit and weep. We accept your challenge and will fulfill our duty in this war. We know that everything you do is to protect yourselves as a class, and we know that the proletariat has the same right. Since you have throttled the workers' press and muzzled their mouths, we will speak their will through the mouth of the gun and the voice of dynamite.

:Do not say we are cowards because we remain hidden; do not call this abominable. This is war, class war... And was it not first waged by you, hiding behind your foolish gunmen slaves, through the powerful institutions you call order under the darkness of your law?

:You tolerate nothing but your own freedom... but workers also have the same right to freedom, and their rights are our rights. We will protect them at any cost.

:We are not many, and we will be fewer than you think, but we are resolved to fight until the last moment. As long as people are buried in your Bastille, as long as workers are tortured in your police system, we will continue to fight until your complete downfall... and until the working masses obtain everything that belongs to them.

:There will be bloodshed, but we will not shy away... There will be murder, but we will kill because it is necessary... There will be destruction, but we will destroy everything to eliminate the world of your oppressive institutions...

:Just as you do anything to prevent the proletarian revolution, we are ready to do anything to overthrow the capitalist class.

:Our mutual positions are very clear. What we have done so far is a warning that friends of public freedom are still alive. The fight has just begun. And now you will see what freedom-loving people can do.

:Do not try to believe that we are agents paid by Germany or the devil. You already know that we are conscious workers with strong determination, devoid of vulgar civic sense. And do not expect your police and bloodhounds to succeed in eradicating the anarchist sprouts pulsating in our veins from this land.

:We know how to take care of ourselves when facing you. And today we are multiplying, so you will not catch all of us. You, who are obsessed with privilege and wealth... now give up and await your destiny.

:Long live the social revolution! Down with tyranny!

Despite his revolutionary zeal, Galleani rejected prefigurative politics, such as those advocated by anarcho-syndicalists. He believed that once the state and capitalism were overthrown, people would instinctively understand how to live as a free and equal society, without the need for pre-planned social organization.

3.4. Ideological Conflicts with Other Anarchists

Galleani engaged in ideological debates with contemporary anarchists, notably Errico Malatesta, particularly concerning the necessity of planning for social organization after a revolution. Malatesta argued that anarchists needed to immediately develop methods for organizing social life to avoid a vacuum, as any interruption in social order should not be permitted. In contrast, Galleani maintained that the primary task of anarchists was the destruction of the existing society, believing that future generations, free from the logic of domination, would instinctively know how to rebuild. Despite these differences, Malatesta did not label Galleani a nihilist, recognizing that their disagreements pertained only to the constructive aspects of the revolution, while they were in complete agreement on the destructive aspects. Malatesta himself was an insurrectionist and a supporter of violent rebellion to eliminate the state.

4. Major Activities and Impact

Luigi Galleani's activities, particularly his prolific publishing and the violent actions of his followers, had a profound impact on society, sparking both a radical movement and a severe government crackdown.

4.1. Press Activities and Spread of Radical Thought

Galleani was instrumental in spreading radical anarchist ideas through his journalistic endeavors. As editor of La Questione SocialeThe Social QuestionItalian and especially as the founder and editor of Cronaca Sovversiva, he provided a consistent platform for his anti-state, anti-capitalist, and anti-reformist views. Cronaca Sovversiva became the most influential Italian anarchist periodical in North America, reaching thousands of subscribers globally. Through its pages, Galleani disseminated his theories of direct action and armed resistance, praising anarchist assassins and advocating for revolutionary violence.

The publication of La Salute è in voi!Health is in You!Italian, a bomb-making manual, further amplified his influence by providing practical instructions for violent acts. This manual, compiled with the help of explosives expert Ettore Molinari, was a direct manifestation of Galleani's "propaganda of the deed" philosophy, providing his followers with the means to carry out attacks. His book Faccia a Faccia col NemicoFace to Face with the EnemyItalian (1914) also played a role in popularizing his radical thought by glorifying anarchist assassins as revolutionary heroes.

4.2. The Galleanist Movement and Violent Incidents

The Galleanisti, Galleani's highly devoted and militant followers, were the direct executors of his philosophy of violent direct action. In retaliation for Galleani's deportation from the United States, the Galleanisti launched a campaign of terrorist attacks.

In April 1919, the Galleanisti sent approximately thirty package bombs to government officials. Most of these bombs were intercepted and disarmed before reaching their intended targets, with only one detonating and injuring the maid of the intended recipient. In June 1919, they carried out a coordinated series of nine bombings across the Northeastern United States. While none of their main targets were killed or gravely wounded, one bomb detonated prematurely outside Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer's house, killing the attacker. Another bomb, placed in a church, detonated after being discovered by police, resulting in the deaths of ten police officers and a bystander.

The Galleanist Mario Buda was alleged to have carried out the devastating Wall Street bombing of 1920, which killed 33 people and caused significant damage. This act was seen as a reprisal for the government's crackdown on anarchists.

4.3. Impact on Social Movements and Government Response

Galleani's activities had a significant influence on social movements of the time, particularly the anti-war movement. During World War I, he became a prominent voice against the conflict, urging his followers to resist conscription and go into hiding, even suggesting escape to Mexico for an impending revolution.

The violent actions of the Galleanisti provoked a severe governmental response, contributing to the climate of fear known as the First Red Scare. The coordinated bombings led directly to widespread political repression, most notably the Palmer Raids. During these raids, many Galleanisti were arrested, including the Italian American anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who were later executed despite a lack of conclusive evidence against them, becoming symbols of perceived injustice. Galleani's own deportation was part of this broader governmental effort to suppress radical foreign agitators.

While Galleani's movement was influential for a time, the intense repression it faced, coupled with internal ideological shifts, led to its decline. An attempt by Romanian American anarchist Marcus Graham to revive the Galleanist movement with the San Francisco-based newspaper Man! in the 1930s was unsuccessful, and the paper ceased publication in 1939. By the time of the defeat of Italian Fascism in World War II, the Italian American anarchist movement had largely dissipated. However, the Galleanist periodical L'Adunata dei Refrattari continued publication until 1971, eventually succeeded by the anti-authoritarian periodical Fifth Estate.

5. Legacy and Evaluation

Luigi Galleani's legacy is complex, marked by both his intellectual contributions to anarchist thought and the controversial, violent methods he advocated.

5.1. Historical Evaluation

Historically, Galleani's figure fell into relative obscurity, receiving limited scholarly attention for many years. Interest in his work began to grow again only in 1982, when The End of Anarchism? received its first English translation. Further English translations of his works were published in a compilation by AK Press in 2006, contributing to a renewed academic and public interest in his radical thought and activities.

Galleani is recognized as a significant figure in insurrectionary anarchism, having articulated a clear and uncompromising vision for social revolution through direct, violent action. His emphasis on revolutionary spontaneity and the rejection of formal organization influenced a segment of the anarchist movement. His writings, particularly those published in Cronaca Sovversiva, provide valuable insight into the radical currents of the early 20th century, especially within Italian immigrant communities in the United States. His unwavering commitment to his ideals, even in the face of severe repression, is also noted.

5.2. Criticism and Controversy

Galleani's legacy is heavily overshadowed by the criticism and controversy surrounding his advocacy of terrorism and violence. His explicit endorsement of assassination and bombings as legitimate tools for social transformation, as detailed in works like La Salute è in voi! and Faccia a Faccia col NemicoFace to Face with the EnemyItalian, has made him a highly polarizing figure. Critics point to the real-world consequences of his ideology, specifically the series of bombings carried out by his followers, the Galleanisti, which resulted in deaths, injuries, and widespread fear.

The "Plain Words" leaflet, found at the scene of Galleanist bombings, clearly articulated a justification for lethal violence in the name of class war. This direct call for destruction and killing, while framed as a response to perceived oppression, is a central point of criticism. Furthermore, his racist characterization of "people of color" in Mexico as "uninterested" racial groups, which led him to reject the possibility of an anarchist revolution there, reflects a significant ethical failing and contradicts universalist principles often associated with revolutionary movements. His anti-organizational stance, while ideologically consistent for him, also contributed to a fragmented and ultimately less effective movement in the long term, making it more susceptible to government repression.

6. Selected Works

- (1914) Contro la guerra, contro la pace, per la rivoluzione socialeAgainst War, Against Peace, For The Social RevolutionItalian

- (1914) Faccia a Faccia col NemicoFace to Face with the EnemyItalian

- (1925) La Fine dell'Anarchismo?The End of Anarchism?Italian

- (1927) Il principio dell'organizzazione alla luce dell'anarchismoThe Principal of Organization to the Light of AnarchismItalian

- (Posthumous) Aneliti e Singulti: MedaglioniGasps and Sobs: MedallionsItalian (a collection of his writings from Cronaca Sovversiva)

7. Related Items

- Propaganda of the deed

- Insurrectionary anarchism

- Sacco and Vanzetti

- Errico Malatesta

- Pietro Gori

- Élisée Reclus

- Max Stirner

- Peter Kropotkin

- Carlo Tresca

- Francesco Saverio Merlino

- Ettore Molinari

- Mario Buda

- Leon Czolgosz

- Gaetano Bresci

- William McKinley

- Umberto I of Italy

- Benito Mussolini

- Haymarket affair

- 1919 United States anarchist bombings

- Wall Street bombing

- Palmer Raids

- First Red Scare

- Italian Workers' Party

- Italian Socialist Party

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Selective Service Act of 1917

- Sedition Act of 1918

- March on Rome

- Class conflict

- Direct action

- Revolutionary spontaneity

- Anarchist communism

- Anti-capitalism

- Anti-statism

- Anti-war movement

- Anti-fascism

- Civil disobedience

- Internationalism

- Illegalism