1. Overview

Lin Zexu (林則徐Lín ZéxúChinese, 30 August 1785 - 22 November 1850), also known by his courtesy name Yuanfu (元撫YuánfǔChinese) and posthumous name Wenzhong (文忠WénzhōngChinese), was a prominent Chinese political philosopher, calligrapher, poet, and official during the Qing dynasty. He served twice as an Imperial Commissioner and as a Governor-General, most notably under the Daoguang Emperor. Lin Zexu is best remembered for his pivotal role in the First Opium War (1839-1842), where his forceful opposition to the opium trade served as a primary catalyst for the conflict.

Lin Zexu was deeply concerned by the devastating impact of opium on China's national wealth and the health of its populace, advocating for strict prohibition to prevent the nation's decline. His determined efforts to eradicate the illicit drug trade, particularly his dramatic destruction of confiscated opium at Humen, cemented his legacy as a national hero and a symbol of resistance against drug abuse and foreign exploitation in China. While lauded for his unwavering moral stance and integrity, some historical assessments also acknowledge a degree of rigidity in his approach, which may have overlooked the complex domestic and international dynamics of the opium crisis. Despite political setbacks and exile, Lin Zexu's commitment to public service and his forward-thinking analysis of international affairs, including his observations on Russia, left a lasting impact on Chinese society and governance.

2. Early Life and Background

Lin Zexu's early life and formative experiences laid the groundwork for his distinguished career and his unwavering commitment to national welfare.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Lin Zexu was born on 30 August 1785, in Houguan (present-day Fuzhou, Fujian Province), towards the end of the Qianlong Emperor's reign. His father, Lin Binri (林賓日Chinese), had faced repeated failures in the imperial examinations and supported the family through a meager living as a teacher. Lin Zexu, the second son, was recognized as "unusually brilliant" from a young age and dedicated himself to his studies, driven by a desire to fulfill his father's aspirations.

With the financial assistance of a wealthy friend of his father, who later became his father-in-law, Lin Zexu was able to pursue his education. His academic prowess culminated in 1811 (the 16th year of the Jiaqing Emperor's reign) when, at the age of 27, he successfully obtained the prestigious position of advanced Jinshi (進士Chinese), the highest scholarly degree, in the imperial examination. In the same year, he gained admission to the Hanlin Academy in Beijing, an elite institution for top scholars.

2.2. Early Career

After joining the Hanlin Academy, Lin Zexu immersed himself in the study of administrative documents, developing a deep understanding of governance. His career progressed rapidly through various provincial appointments, where he distinguished himself as a capable and upright official. He actively engaged in critical social issues of the time, focusing on rural reconstruction and crucial water management projects. He was also known for his resolute stance against corruption, taking decisive action to punish dishonest officials. His administrative skills as a local official are highly regarded even today. It is believed that his strong commitment to eradicating opium, which became a central focus of his later career, was significantly shaped by his experiences during these early provincial assignments.

Lin Zexu's pragmatic approach to governance extended to his views on foreign relations. While he generally opposed the complete opening of China to the outside world, he recognized the critical need for a better understanding of foreign nations. This conviction led him to meticulously collect materials for a comprehensive geography of the world. He later entrusted these valuable materials to Wei Yuan, who subsequently published the influential Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms (海國圖志Hǎiguó TúzhìChinese) in 1843. Lin Zexu's interest in Western knowledge underscored his pragmatic views, acknowledging foreign influence while steadfastly resisting Western domination.

In 1832, at the age of 48, Lin Zexu was appointed Governor of Jiangsu Province. During his tenure in Jiangsu (1832-1833), he twice submitted memorials to the imperial court, expressing his profound concern over the devastating impact of opium. He articulated that if the opium trade was not completely suppressed, "the country would grow poorer each day, and the people weaker each day; in just over a decade, the Central Plains would no longer have strong armies to resist the enemy, nor silver ingots to fund military provisions."

In March 1837, he was promoted to Governor-General of Huguang (the combined provinces of Hubei and Hunan). In this role, he successfully launched a vigorous campaign against the trading of opium within his jurisdiction, achieving notable results. His achievements in opium eradication and the precision of his arguments earned him the attention and high regard of the Daoguang Emperor. In 1838, the Emperor, deeply moved by Lin's warnings about the drain of silver from the national treasury due to opium imports and the deteriorating condition of the populace, appointed Lin Zexu as an Imperial Commissioner with the specific mandate to halt the illicit importation of opium by the British in Guangzhou. This appointment marked a pivotal moment in China's anti-opium efforts, reflecting Lin's strong moral stance against the drug trade and his growing influence in Qing policy.

3. Major Activities and Achievements

Lin Zexu's career was defined by his resolute campaign against the opium trade, which directly led to the First Opium War, and his intellectual curiosity regarding the Western world.

3.1. Campaign Against Opium

Lin Zexu's mission to eradicate the opium trade in China was characterized by his firm moral conviction and decisive administrative actions.

3.1.1. Dispatch to Guangzhou and Preparation

The Daoguang Emperor appointed Lin Zexu as Imperial Commissioner in 1838, entrusting him with the immense responsibility of suppressing the opium trade in Guangdong, the epicenter of the crisis. Lin Zexu understood the gravity of his mission, famously stating to his friends before departing, "Good or bad fortune, I don't care about death anymore. Before opium is destroyed, I will never return to the capital."

After a two-month journey, Lin Zexu arrived in Guangzhou on 10 March 1839. Crowds of people gathered along the banks of the Pearl River, eagerly awaiting the Imperial Commissioner. The day after his arrival, Lin posted two public notices: one announcing his purpose to investigate port incidents, and the other declaring a strict crackdown on opium. These announcements were his initial steps to address the complex situation in Guangzhou, signaling his presence to officials, common people, and foreigners alike.

Lin Zexu conducted extensive investigations both during his journey to Guangzhou and for several days after his arrival. On 18 March, he summoned and interrogated the 13 Hong merchants, a group of specially authorized trading houses that monopolized foreign trade, including tea and silk. These merchants were often complicit in opium smuggling, acting as intermediaries for foreign traders. Lin Zexu learned that foreign companies, particularly the British, were refusing to forfeit their opium stores. He initially attempted to persuade them to surrender their opium in exchange for tea, but this effort failed.

Lin Zexu then resorted to more forceful measures. He gathered foreign merchants and issued a stern ultimatum, demanding that they unload and surrender all their opium supplies. He gave them three days to comply, threatening to seal their opium dens and close the port if they refused. He also required them to sign a bond pledging not to bring opium to China again, warning that any future discovery of opium would result in the confiscation of their entire cargo and the arrest of those involved. A local opium dealer named Wu Shaorong attempted to bribe Lin Zexu, but Lin angrily rebuked and expelled him, demonstrating his incorruptibility.

Lin Zexu also penned an open letter to Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, published in Canton, urging her to end the opium trade. In this memorial, he argued that China provided Britain with valuable commodities like tea, porcelain, spices, and silk, while Britain reciprocated only with "poison." He accused foreign traders of being obsessed with profit and devoid of morality. Lin Zexu believed that opium was strictly prohibited in the United Kingdom and questioned the morality of Queen Victoria supporting its trade in China. He wrote:

"We find that your country is sixty or seventy thousand li from China. The purpose of your ships in coming to China is to realize a large profit. Since this profit is realized in China and is in fact taken away from the Chinese people, how can foreigners return injury for the benefit they have received by sending this poison to harm their benefactors? They may not intend to harm others on purpose, but the fact remains that they are so obsessed with material gain that they have no concern whatever for the harm they can cause to others. Have they no conscience? I have heard that you strictly prohibit opium in your own country, indicating unmistakably that you know how harmful opium is. You do not wish opium to harm your own country, but you choose to bring that harm to other countries such as China. Why? The products that originate from China are all useful items. They are good for food and other purposes and are easy to sell. Has China produced one item that is harmful to foreign countries? For instance, tea and rhubarb are so important to foreigners' livelihood that they have to consume them every day. Were China to concern herself only with her own advantage without showing any regard for other people's welfare, how could foreigners continue to live? I have heard that the areas under your direct jurisdiction such as London, Scotland, and Ireland do not produce opium; it is produced instead in your Indian possessions such as Bengal, Madras, Bombay, Patna, and Malwa. In these possessions the English people not only plant opium poppies that stretch from one mountain to another but also open factories to manufacture this terrible drug. As months accumulate and years pass by, the poison they have produced increases in its wicked intensity, and its repugnant odor reaches as high as the sky. Heaven is furious with anger, and all the gods are moaning with pain! It is hereby suggested that you destroy and plow under all of these opium plants and grow food crops instead, while issuing an order to punish severely anyone who dares to plant opium poppies again. A murderer of one person is subject to the death sentence; just imagine how many people opium has killed! This is the rationale behind the new law which says that any foreigner who brings opium to China will be sentenced to death by hanging or beheading. Our purpose is to eliminate this poison once and for all and to the benefit of all mankind."

This letter, though it reportedly never reached Queen Victoria (sources suggest it was lost in transit), was later reprinted in the London The Times as a direct appeal to the British public. Lin Zexu's policies were widely welcomed by the local population, who were deeply troubled by the rampant spread of opium. An edict from the Daoguang Emperor followed on 18 March, emphasizing the severe penalties that would now apply to opium smuggling.

3.1.2. Opium Confiscation and Destruction

In March 1839, Lin Zexu began implementing his measures to eliminate the opium trade. He arrested more than 1,700 Chinese opium dealers and confiscated over 70,000 opium pipes. When foreign companies continued to resist his ultimatum, Lin Zexu took decisive action by imposing a ban on all trade between China and Britain. He closed the British East India Company's operations and severed their connections with the outside world. The Chinese navy was deployed to monitor foreign vessels and pressure foreign opium merchants to surrender their goods.

Under this immense pressure, Charles Elliot, the British Superintendent of Trade in China, had no choice but to instruct British merchants to cooperate with the Chinese government. Other foreign opium traders also capitulated. From 12 April to 21 May, Lin Zexu's forces confiscated over 20,000 chests of opium, including 1,540 chests from American merchants, totaling approximately 2.6 M lb (1.20 M kg).

On 3 June 1839, a momentous public destruction of the confiscated opium began at Humen Town on the coast. Two large pits were dug, and a high platform was erected in the middle. A massive crowd gathered to witness this historic event. Lin Zexu, with great authority, ascended the platform and gave the order to commence the destruction. Five hundred workers labored for 23 days, mixing the opium with lime and salt, which chemically reacted to render the opium unusable, before throwing it into the sea. The destroyed opium flowed like mud into the open ocean, accompanied by loud cheers and applause from the spectators. Lin Zexu even composed an elegy, apologizing to the gods of the sea for polluting their realm.

3.1.3. Diplomacy and Conflict with Britain

Historian Jonathan Spence noted that Lin Zexu and the Daoguang Emperor seemed to believe that the citizens of Canton and the foreign traders there possessed "simple, childlike natures" that would respond to firm guidance and clear moral principles. However, neither Lin nor the emperor fully grasped the depth and changing nature of the problem, including the evolving international trade structures, the British government's commitment to protecting private traders' interests, and the significant peril faced by British traders if they surrendered their opium.

Open hostilities between China and Britain commenced in 1839, marking the beginning of what would become known as the First Opium War. Immediately following the opium destruction, both sides, through the declarations of Charles Elliot and Lin Zexu, banned all trade. Lin Zexu had also pressured the Portuguese government in Macau, leaving the British without refuge except for the barren and rocky harbors of Hong Kong.

3.2. The Opium War

The First Opium War was a direct consequence of the escalating tensions over the opium trade, fundamentally altering China's relationship with the Western powers.

3.2.1. Causes and Progression

The underlying causes of the First Opium War were multifaceted, stemming from the clash between China's efforts to suppress the opium trade and Britain's determination to protect its commercial interests and expand its influence. Lin Zexu's aggressive anti-opium campaign, particularly the destruction of the confiscated opium, served as the immediate trigger for the conflict.

Anticipating a potential British invasion, Lin Zexu had made significant preparations for war. He ordered the fortification of coastal defenses, acquired over 300 Western cannons, and purchased a Western-style ship named Cambridge and a steamship. He also recruited an additional 5,000 men for the navy and oversaw regular target practice. To better understand the enemy, Lin Zexu dispatched agents to Macau to purchase Western newspapers and gather intelligence on the latest developments. He established an office in Guangzhou dedicated to translating foreign documents on world politics, history, and geography, compiling works such as Hua Shi Yi Ngon Luc Yeu (華事夷言錄要Huáshì Yíyán LùyàoChinese, "Key Records of Barbarian Sayings on Chinese Affairs") and Si Zhou Zhi (四洲志Sìzhōu ZhìChinese, "Gazetteer of Four Continents"). He also enlisted the help of American missionary doctor Peter Parker to translate parts of Emer de Vattel's The Law of Nations. Through these efforts, Lin Zexu systematically studied the British military to devise effective strategies and tactics.

Lin Zexu's strategic approach was encapsulated by the principle: "Take defense as offense, strengthen our army, and tire the enemy." He organized his forces, deployed defenses, mobilized ships, and rigorously trained the navy. In January 1840, under Lin Zexu's command, the Qing navy launched a surprise four-pronged night attack on British ships. The British, caught off guard, were reportedly terrified, and the Qing forces managed to burn 23 of their ships, forcing the remaining vessels to flee. In April 1840, when over 30 British warships encroached upon the Guangdong coast, firing on fishing boats and coastal residents, Lin Zexu devised a "fire attack" plan. In May, Chinese fire ships successfully approached the British fleet, setting more than 10 warships ablaze and causing panic among the British forces. Lin Zexu's leadership and the determined resistance of the Guangdong military and populace successfully repelled British attacks, preventing them from gaining a foothold in the region.

However, the British, facing strong resistance in Guangdong, shifted their focus northward. In June 1840, a British naval fleet, including the East India Company's steam warship Nemesis and equipped with improved weaponry, easily landed and occupied Dinghai in Zhejiang Province. The governors of Jiangsu and Zhejiang had failed to heed Lin Zexu's warnings and were unprepared for the invasion. This unpreparedness was partly due to pervasive corruption and inefficiency within the Qing dynasty's local governments, which hampered their ability to respond effectively.

3.2.2. Results and Impact

The Qing government's weakness and corruption ultimately led to military defeat. Lin Zexu became a scapegoat for these losses due to court politics, despite his earlier successes in Guangdong. In September 1840, he was dismissed as Imperial Commissioner and exiled to the remote Ili region in Xinjiang. His position was then given to Qishan.

The Qing government, under pressure from the British advance towards Tianjin and Beijing, was forced to negotiate. The Daoguang Emperor, influenced by corrupt ministers like Qishan, adopted a submissive stance towards Britain. As a result, China was compelled to sign the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, an unequal treaty that imposed significant concessions on China, including the opening of treaty ports and the payment of war indemnities totaling 8 million taels of silver to both Britain and France. This defeat marked a profound turning point in China's history, ushering in an era of increased foreign intervention and significant social and political upheaval.

3.3. Intellectual Pursuits and Writings

Beyond his administrative and military roles, Lin Zexu was a keen intellectual who recognized the importance of understanding the Western world.

During his tenure in Guangdong, Lin Zexu actively pursued knowledge about the West. He recruited English-speaking scholars, such as Yuan Dehui, to his staff and collaborated with American missionary doctor Peter Parker from the Guangzhou Medical Missionary Society. Through these efforts, he translated and collected a wide range of Western materials, including English magazines, geographical texts, international law treatises, and documents on military technology. This research allowed Lin Zexu to gain a more realistic understanding of foreign nations, leading him to conclude that a complete ban on foreign trade and shipping was impractical and impossible. His knowledge also prevented the British from exploiting the Qing government's ignorance of Western affairs.

After his dismissal and while en route to his exile in Xinjiang, Lin Zexu visited his close friend and junior scholar, Wei Yuan, in Yangzhou. He entrusted Wei Yuan with his extensive collection of translated Western documents and materials. Based on these resources, Wei Yuan compiled and published the influential Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms (海國圖志Hǎiguó TúzhìChinese) in 1843. This work, which aimed to inform Chinese officials about the outside world and advocate for learning from Western strengths to counter them, was also transmitted to Japan, where it profoundly influenced Japanese intellectuals during the late Edo period in their understanding of international affairs and national defense.

3.3.1. Observations on Russia

During his period of exile in the Ili region of Xinjiang, Lin Zexu gained firsthand experience of China's border with the Russian Empire. For three years, until his recall from exile, he dedicated himself to studying Russia, compiling his observations into a work titled Eluosi Guo Jiyao (俄羅斯國紀要Éluósī GuójìyàoChinese, "Summary of Russia"). Based on his experiences with both Britain and Russia, Lin Zexu concluded that Russia posed a greater long-term threat to China's national security than Britain. He conveyed this foresight to various influential officials with whom he corresponded. His son-in-law, Shen Baozhen, later adopted this perspective. In 1849, after stepping down as Governor-General of Yun-Gui, Lin Zexu met Zuo Zongtang in Changsha on his journey back to Fujian and provided him with his collected materials on Russia. These figures, along with others who prioritized defense against Russia, came to be known as the "Saifang faction" (塞防派Sāifáng PàiChinese, "Border Defense Faction"). Lin Zexu's prediction proved prescient, as Ili was indeed occupied by Russia in July 1871.

While in Xinjiang, Lin Zexu also became the first Chinese scholar to extensively document various aspects of local Muslim culture. In 1850, he noted in a poem that the Muslims in Ili did not worship idols but instead bowed and prayed to tombs adorned with poles from which the tails of cows and horses were attached. This practice reflected the widespread shamanic tradition of erecting a tugh, and Lin Zexu's record was its first documented appearance in Chinese writings. He also recorded several Kazakh oral tales, including one about a green goat spirit of the lake whose appearance foretold hail or rain. Lin Zexu's documentation of these practices significantly contributed to a broader understanding of the diverse ethnic minorities within the Qing Empire at the time.

4. Exile and Later Career

Lin Zexu's career faced a significant setback with his exile, but his resilience and dedication to governance saw him return to public service.

4.1. Exile in Xinjiang

Following the Qing dynasty's defeat in the First Opium War and the subsequent signing of the Treaty of Nanjing, Lin Zexu was made a scapegoat for the losses, largely due to internal court politics and the Emperor's desire to appease the British. As punishment, he was dismissed from his post as Imperial Commissioner and exiled to the remote Ili region in Xinjiang.

Despite the harshness of his banishment, Lin Zexu did not cease his commitment to public service. During his time in Xinjiang, he implemented agricultural reforms and actively promoted water conservancy projects, which greatly benefited the local population. His efforts earned him the respect and admiration of the residents, and some of the water management techniques he introduced are still used in Xinjiang and Gansu today. This period of exile also proved to be intellectually fruitful, as it allowed him to gain firsthand insight into the geopolitical threats posed by the southward expansion of the Russian Empire, which he documented in his writings.

4.2. Rehabilitation and Return to Office

The Qing government eventually recognized Lin Zexu's contributions and rehabilitated his political standing. In 1845, he was appointed Governor-General of Shaan-Gan (covering Shaanxi and Gansu provinces). In 1847, he was further appointed Governor-General of Yun-Gui (covering Yunnan and Guizhou provinces). While these posts were considered less prestigious than his previous position in Guangzhou, his career never fully recovered to its pre-war prominence. Nevertheless, Lin Zexu continued to advocate for reforms in opium policy and diligently addressed issues of local governance and corruption. His efforts, though perhaps limited in scope compared to his earlier imperial commission, remained influential in shaping Qing policy and demonstrating his unwavering dedication to the nation.

5. Death

Lin Zexu retired from his post as Governor-General of Yun-Gui in 1849. However, in 1850, he was recalled to public service by the Qing government to help suppress the burgeoning Taiping Rebellion in Guangxi Province. While en route to his new assignment, Lin Zexu fell ill and died on 22 November 1850, in Puning, Guangdong. He was 65 years old.

6. Assessment and Legacy

Lin Zexu's historical significance is profound, marked by his enduring impact on Chinese society and his recognition as a national hero and moral exemplar.

6.1. Historical Assessment

Lin Zexu's actions and character have been subject to diverse historical assessments. Initially, he was blamed for precipitating the First Opium War, and his dismissal and exile were a direct consequence of this official condemnation. However, in the later years of the Qing dynasty, as efforts to eradicate opium production and trade were renewed, Lin Zexu's reputation was rehabilitated. He became a powerful symbol of the fight against opium and other illicit drug trades, with his image displayed in parades and his writings frequently quoted by anti-opium reformers.

English sinologist Herbert Giles praised and admired Lin Zexu, describing him as "a fine scholar, a just and merciful official and a true patriot." This sentiment is widely echoed in China, where Lin Zexu is popularly viewed as a national hero and a cultural icon against drug abuse. He is celebrated for his integrity, his unwavering moral conviction, and his foresight in recognizing the dangers of opium to the nation's well-being and its ability to resist foreign exploitation. Many Chinese historians and the public deeply regret his dismissal, believing that if he had remained in power in Guangdong, he might have successfully repelled the British.

However, some historians, such as Jonathan Spence, have also pointed to a more nuanced perspective. Spence suggests that Lin Zexu and the Daoguang Emperor may have underestimated the complexities of the international situation, believing that foreign traders would respond to simple moral guidance. They did not fully appreciate the profound changes in international trade structures, the British government's commitment to protecting private commercial interests, or the severe risks faced by British traders if they were to surrender their valuable opium. Furthermore, Lin Zexu's rigid approach and his proposal for the redevelopment of Zhili (the capital region) reportedly angered other high-ranking officials who had vested interests in the region or resented what they perceived as criticism of their past work. His dismissal was partly fueled by resentment from corrupt officials in Guangdong who had lost their illicit income due to his strict anti-corruption measures.

Despite these criticisms, Lin Zexu's legacy as a clean, selfless official who consistently prioritized the nation's interests, even during his exile, is deeply respected. He is also recognized as one of the first Chinese intellectuals to advocate for a broader "world view," urging his countrymen to understand and learn from advanced Western knowledge to strengthen China.

6.2. Cultural Impact and Commemoration

Lin Zexu's influence extends deeply into Chinese culture, literature, and public memory. His former home, located in Fuzhou's historic Sanfang-Qixiang ("Three Lanes and Seven Alleys") district, is now open to the public as a memorial. It meticulously documents his extensive work as a government official, covering not only his anti-opium campaign but also his efforts to improve agricultural methods, champion water conservation (including his successful project to save Fuzhou's West Lake from being converted into a rice field), and combat corruption.

His unwavering stance against opium has led to significant commemorations. June 3, the day he confiscated and destroyed the chests of opium at Humen, is unofficially celebrated as Opium Suppression Movement Day in Taiwan. More broadly, June 26 is recognized globally as the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking by the United Nations, a tribute to Lin Zexu's pioneering work against illicit drugs.

Monuments to Lin Zexu have been erected in Chinese communities worldwide, reflecting his status as a national hero. A notable statue stands in Chatham Square in Chinatown, Manhattan, New York City, with its base inscribed with "Pioneer in the war against drugs" in both English and Chinese. A wax statue of Lin Zexu has also been displayed at Madame Tussauds wax museum in London.

Lin Zexu has been depicted in various forms of media. He appeared as a character in River of Smoke, the second novel in the Ibis trilogy by Amitav Ghosh, which uses the Opium Wars as its setting to explore themes of globalization. He was also portrayed in the 1997 Chinese film The Opium War.

Lin Zexu's grandson, Lin Taizeng, served as a Commodore in the Beiyang Fleet and commanded the battleship Zhenyuan, one of China's modern battleships purchased from Germany in the 1880s. Tragically, Lin Taizeng committed suicide with an opium overdose after his ship ran aground during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). Descendants of Lin Zexu continue to live in Fuzhou, Jieyang (Puning), Meizhou, and other areas across China, as well as in the United States.

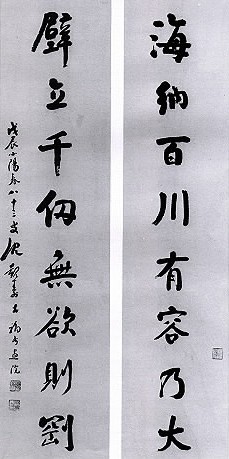

Lin Zexu is also remembered for a famous couplet he wrote while serving as an imperial envoy in Guangdong:

海納百川,有容乃大。壁立千仞,無欲則剛。Chinese

"The sea accepts the waters of a hundred rivers, its tolerance results in its grandeur. The cliff towers to a height of a thousand ren (approximately 1.6 mile (2.5 km)), its lack of desire gives it its resilience."

The first half of this couplet has been adopted as the motto for the Chinese Wikipedia. Additionally, Lin Zexu authored "Ten Useless Sayings" (十無益Shí WúyìChinese), a series of ten maxims with accompanying poems, which offer profound educational insights and remain widely read for their moral guidance.