1. Overview

Lee Jung-seob (이중섭Korean, 李仲燮Japanese; April 10, 1916 - September 6, 1956), whose art name was Daehyang (대향Korean), was a prominent Korean painter recognized for his distinctive oil paintings and his profound impact on modern Korean art. Despite a life marked by poverty, the Korean War, and personal struggles, Lee Jung-seob's art captured the essence of Korean identity and the innocence of childhood, earning him the title of "National Painter" posthumously. His most celebrated works often feature bulls, children, and family scenes, rendered with vigorous brushstrokes and a unique, expressive style. This article explores his life journey, the evolution of his artistic style, the reception of his works, and his enduring legacy in Korean culture.

2. Life

Lee Jung-seob's life was a poignant journey marked by artistic passion, deep familial love, and immense personal hardship, deeply intertwined with the tumultuous history of Korea in the mid-20th century.

2.1. Early life and family background

Lee Jung-seob was born on April 10, 1916, in Pyongwon County, South Pyongan Province, in present-day North Korea, during the period of Korea under Japanese rule. He hailed from an affluent family of the Jeonju Yi clan that owned extensive land. His elder brother, twelve years his senior, managed the largest department store in Wonsan at the time and assumed a paternal role after their father's death in 1918. The family's wealth provided Lee with the opportunity to pursue his artistic aspirations. He attended Jongno Primary School in Pyongyang, where he first discovered his artistic calling upon encountering replicas of Goguryeo tomb murals at the Pyongyang Prefectural Museum. These grand and vivid wall paintings deeply mesmerized the young Lee.

2.2. Education

In 1930, Lee Jung-seob began his formal art studies at Osan High School in Jeongju, an institution independently funded by Korean Christian nationalists dedicated to nurturing future leaders in defiance of Japanese colonialism. At Osan, Lee was profoundly inspired by his art teacher, Im Yong Ryeon, who had studied Western painting at the Art Institute of Chicago (1923-1926) and the Yale School of Fine Arts (1926-1929). Im Yong Ryeon instilled in Lee a love for Goguryeo tomb murals and encouraged him to sign his artworks in Korean, circumventing colonial regulations on the use of Hangul. Lee notably signed one of his early bull paintings as 'Dung-seob' instead of 'Jung-seob' to express his anger at a pro-Japanese article published in the pro-Japanese newspaper Maeil Sinbo, which advocated for Korean youth to shave their heads like monks and participate in the war.

In 1936, Lee enrolled in Teikoku Art School (now Musashino Art University) in Tokyo, Japan, to seriously pursue Occidental painting. However, he left in 1937 to join Bunka Gakuin (文化學院Japanese), a private academy known for its liberal and avant-garde artistic environment. At Bunka Gakuin, Lee developed Fauvism tendencies and a strong, free-flowing drawing style. It was during this period that the bull became a central subject in his paintings, symbolizing his own pursuit of Korean modernism. He also joined the Free Artists' Association (自由美術家協会Japanese, Jiyū Bijutsuka Kyōkai) after his exhibited works received critical acclaim, and in 1943, he received the Taiyo Prize from the Free Artists' Association. While at Bunka Gakuin, he was nicknamed "Agori" (顎の李, "Lee of the Jaw") due to having three students named Lee in the department, and he met and fell deeply in love with a junior colleague, Yamamoto Masako (山本方子Japanese), who was nicknamed "Asparagus" for her slender legs and who would later become his wife. In 1941, he co-founded the Joseon New Artists' Association with other Korean artists studying in Tokyo.

2.3. Marriage and Family Life

Despite the escalating tensions of the Pacific War, Lee Jung-seob continued his liberal education at Bunka Gakuin, graduating in 1941. As wartime panic grew in Tokyo, he returned to his hometown of Wonsan in 1943. He continued to paint and organize art exhibitions in Seoul and Pyongyang, undeterred by the wartime emergency. In April 1945, Yamamoto Masako traveled to Wonsan amidst the bombing of Japan, and they were married the following month.

In 1946, Lee worked as an art teacher at Wonsan Normal School for one week before resigning. The same year, their first child was born but tragically died suddenly from diphtheria. This loss deeply affected Lee, who was then a relatively unknown artist preparing for an exhibition. Inspired by his grief, he sent his painting A Child Flies with a White Star to an exhibition commemorating the Korean independence movement in 1947. He was also implicated in the "Eunghyang Incident" in 1946, a literary purge where the poetry collection Eunghyang by his friend Ku Sang was deemed decadent and anti-people by the authorities. His son Taehyun was born in 1947, followed by his second son, Taeseong, in 1949. Yamamoto Masako later adopted the Korean name Lee Nam-deok (이남덕Korean).

2.4. Korean War and Displacement

The end of World War II brought new challenges to Korea, with Soviet forces occupying the North and U.S. forces the South. The communist regime established itself in Wonsan, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of Lee's brother. Lee himself was closely monitored due to his brother's entrepreneurial success, his wealthy Catholic Japanese wife, and his art, which expressed his thoughts and ideas.

With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Wonsan came under bombing. As part of a mass exodus to South Korea, Lee, his wife, and their two sons sought refuge in Busan in December 1950. He was forced to leave his mother and most of his artwork behind, resulting in the loss of nearly all his pre-1950 creations. The family faced desperate poverty. Finding Busan overcrowded with other refugees, and seeking a warmer climate, Lee moved his family further south to Jeju Island, the southernmost tip of Korea.

2.5. Life in Jeju and Tongyeong

On Jeju Island, Lee and his family found a warm and pleasant life in Seogwipo, on the southern coast. Despite their impoverished circumstances, they spent a largely happy year together. Lee's painting A Family on the Road (1951) depicts a father leading a golden bull and a wagon carrying a mother and two sons, tossing flowers and searching for Utopia. Inspired by the local scenery, Lee sketched and painted his surroundings, finding new subjects in seagulls, crabs, fish, the coast, and his growing children. During this period, he developed a more simplified linear style, often depicting children alongside fish and crabs within compact, abstract landscapes. By the end of 1951, financial hardships on the island severely impacted the family's health, forcing them to return to Busan in December, where they moved between refugee camps for Japanese nationals.

Seogwipo held significant geographical and emotional meaning for many of Lee's works, reflecting his deep affection for the home he found there. He created some of his most renowned pieces during his stay on the island, including Boys, Fish, and Crab (1950), Song of the Ocean of Lost Hometown (1951), The Sun and Children (1950s), A Family Dancing Together (1950s), Children in Spring (1952-53), and Children in the Seashore (1952-53).

From the end of the Korean War until June 1954, Lee worked as a lecturer in Tongyeong. This period offered him a rare sense of stability since the war's outbreak. He spent his year in Tongyeong feverishly producing a wealth of art pieces, including his famous Bull series and a series of oil paintings capturing the beautiful Tongyeong landscape. It was here that he held his first solo exhibition.

2.6. Separation from Family and Personal Struggles

Overwhelmed by destitution, Lee's wife, Masako, left for Japan with their children in July 1952, a temporary arrangement intended to alleviate their suffering. Unable to secure a visa to accompany them, Lee became deeply depressed and yearned intensely for his family. He regularly sent letters and postcards adorned with drawings to his wife and children, expressing his profound love and longing for reunion. He took a job as a crafts teacher and continued to create paintings, magazine illustrations, and book covers, while also participating in exhibitions. Unfortunately, most of his works produced in Busan during this time were lost in a fire. Lee later returned to Seoul.

Poet Ku Sang, a close friend of Lee's, recounted Lee's desperate struggle to sell his art in hopes of reuniting with his family in Japan. The pain and agony of losing that hope led to Lee's self-torture and eventual mental illness. Lee drew Family of Poet Ku Sang (1955), a work that expressed his yearning for familial love through the portrait of Ku gifting his young son a tricycle. Despite his efforts, Lee was never able to save enough money to move to Japan and be reunited with his family permanently. He only met them once more for a brief five-day period in Tokyo in 1953, which would be their final encounter.

In January 1955, Lee held a private exhibition at the Midopa Gallery in a last-ditch effort to sell his works. Although the exhibition was successful, with twenty works sold, he remained heavily in debt as he often received payment in goods or faced delayed payments instead of money. He reportedly only received enough to treat his colleagues and juniors to drinks. This failure to provide for his family plunged Lee into deep self-reproach and depression. Ku Sang helped him organize another final exhibition at the Gallery of the US Information Service in Daegu in April, which yielded even worse results than the Seoul exhibition. Lee spiraled into a profound depression, castigating himself for failing not only as a family provider but also as an artist.

2.7. Death

Lee Jung-seob suffered from a type of schizophrenia, attributed to his intense longing for his family and the overwhelming stress from life's hardships. In his profound loneliness, Lee turned to alcohol and developed severe anorexia. He continued a migratory lifestyle, moving between Seoul, Daegu, and Tongyeong until his death. He spent his final year in various hospitals and the homes of friends, working on illustrations for literary magazines, including his River of No Return series.

On September 6, 1956, Lee Jung-seob died of hepatitis at the age of 40, alone at Seoul Red Cross Hospital, recorded as a "death of a person without known domicile". His friends eventually located him and arranged for his cremation, sending some of his ashes to Masako in Japan. They also commissioned a tombstone for him at Manguri Public Cemetery in Seoul.

3. Artistic Style and Works

Lee Jung-seob's artistic journey was a continuous exploration of style and theme, deeply rooted in his personal experiences and a profound connection to Korean identity.

3.1. Artistic Influences and Development

Lee's artistic foundation was laid at Osan School under Im Yong Ryeon, who introduced him to Western painting techniques. Lee inherited a deep appreciation for Goguryeo tomb murals, which manifested in his vigorous line work, deep colors, circular compositions, and symbolic animal motifs. The active introduction of Western-style painting in Pyongyang by artists returning from Japan's Tokyo School of Fine Arts further familiarized Lee with modern techniques such as watercolor, drawing (dessinFrench), and oil painting.

In Tokyo, Lee's style was influenced by Fauvism and Expressionism, yet his themes remained distinctly Korean and indigenous. His works often depicted everyday life in Korea, including rural landscapes, scenes of his family's village and island life, and traditional Korean dress. He made significant contributions to the introduction of Western styles in Korea while infusing them with a unique Korean sensibility. His inspirations included artists like Georges Rouault and Pablo Picasso. Lee always harbored a dream of painting a large-scale mural in a public space for the enjoyment of many, but this dream remained unrealized due to the turmoil of the Korean War and its aftermath.

3.2. Major Themes and Series

Lee Jung-seob's oeuvre is characterized by recurring subjects that reflect his life, emotions, and national identity.

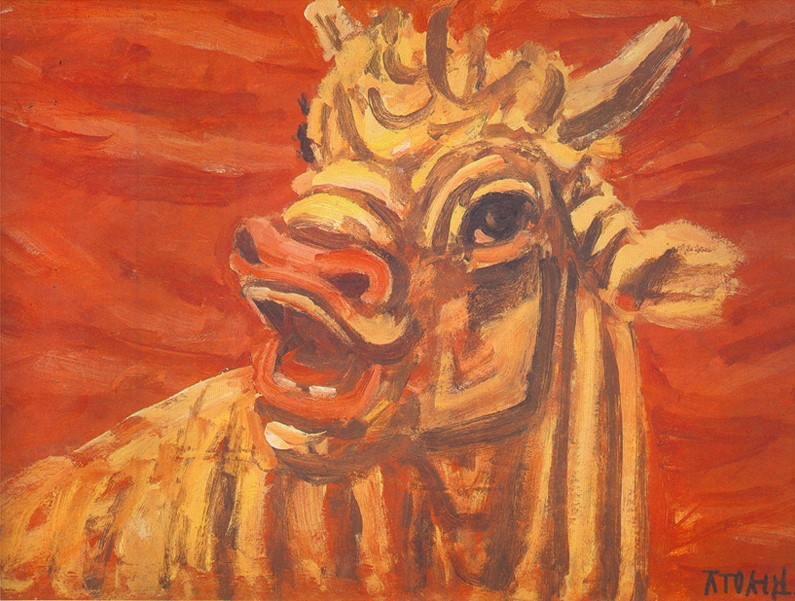

- Cows and Bulls: Throughout his life, the cow held a special place in Lee's artistic universe, appearing in numerous paintings. The cow symbolized the deep roots of the Korean people and served as a modernist reflection of self. The white bull, in particular, came to symbolize Korea and its "white-robed people." Scholars argue that this subject matter was a bold choice during the colonial era when Korean motifs were actively suppressed by Japan. After the war, Lee returned to bull paintings, imbuing them with a sense of confidence and strong will. He used vivid colors and strong brushstrokes in works like Bull (1953) to express the determined hope he held for a reunion with his family. Lee once famously said, "When I look into a cow's big eyes, I know happiness." Other notable cow paintings include White Ox (1954), A White Bull (1953-54), Gray Bull (1956), and Fighting Ox (1950s).

- Children and Family Life: Much of Lee's subject matter focused on children, often his own, drawing inspiration from the iconography of children playing together on Goryeo period celadon vessels and small sculptures of baby Buddha. After the tragic death of his first child, Lee buried a drawing of children playing with him, hoping he could play with other children in the afterlife. Despite years of strife, poverty, transience, and warfare, Lee produced paintings that conveyed the innocent, childlike beauty of happy days spent with his family, often as a counterpoint to the harshness of reality. Works include Family with Chickens (1954-55), Twins (1950), The Sun and Children (1950s), Children Playing in the Peach Garden (1954), and Tugye (Fighting Chickens, 1955).

- Tinfoil Paintings: Unable to afford traditional art materials during his impoverished years, Lee developed an innovative technique for creating line paintings on pieces of tinfoil salvaged from cigarette packs. He used an awl to scratch lines into the tinfoil, applied paint, and then wiped it away, leaving only the etched lines tinted. Although a flat image, the deeply indented lines created an impression of multiple layers, and the shiny, metallic surface enhanced the aesthetic effect. This technique echoed the tradition of inlaid Goryeo celadon or metalware inlaid with silver, reflecting Lee's deep reverence for Korean tradition. He is believed to have produced approximately 300 tinfoil paintings. These works range from scenes of poverty and social adversity to depictions of his happiest moments in Seogwipo, generally portraying the family he desperately longed for, happily playing with crabs, fish, and flowers. The tinfoil paintings were intended as rough sketches for the large murals he dreamt of creating. This is his most famous type of work, with three pieces housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and three others displayed in the Seogwipo gallery. Notable examples include Twins (1950) and Children Playing in the Peach Garden (1954).

- Letter Paintings: From the time he was separated from his family, Lee regularly sent letters to his wife and children in Japan. Early letters were affectionate and joyful, brimming with hope for an imminent reunion. Many of these letters featured free-flowing handwriting and delightful illustrations for his family, reflecting his deep love. However, from mid-1955, Lee descended into despair and almost entirely stopped writing to his family, reportedly also ceasing to read the letters his wife sent him. An estimated sixty letters, comprising about 150 pages, have survived. These letters, such as Artist Drawing His Family (1953-54), hold significant documentary value, revealing the intricate relationship between Lee's daily life and his art, and are considered important independent art pieces in themselves.

4. Exhibitions and Reception

Lee Jung-seob's journey from relative obscurity to national recognition was largely posthumous, with his art gaining widespread appreciation years after his death.

4.1. Major Exhibitions

During his lifetime, Lee Jung-seob held a significant solo exhibition at the Midopa Department Store in Seoul in January 1955. Despite selling twenty works, he received meager financial returns, often in goods or delayed payments, which contributed to his profound despair. Another exhibition, organized with the help of his friend Ku Sang at the Gallery of the US Information Service in Daegu in April 1955, yielded even worse results.

A pivotal posthumous exhibition held in Lee's honor in 1957 drew considerable public attention to his artworks, marking the beginning of his rise to prominence.

4.2. Posthumous Evaluation and Reputation

Lee Jung-seob is widely regarded as one of the most important artists in Korean history. His posthumous exhibition in 1957 was instrumental in bringing his art to public attention. He achieved the distinction of being the first Korean artist to have a piece represented in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Lee aspired to be known as a painter of the Korean people, and his works indeed reflected a unique Korean modernism while embodying the traditional aesthetics of his country. His paintings portray the hopes and desires of an individual amidst oppressive violence, poverty, and desperation. The tragic story of his life serves as a powerful reminder of the devastating effects of war on individuals and families. In 1978, he was posthumously awarded the Silver Crown Order of Cultural Merit, solidifying his status as a beloved "National Painter" in Korean modern art.

5. Legacy and Impact

Lee Jung-seob's art and life have left an indelible mark on Korean culture and society, securing his place as a pivotal figure in modern art and ensuring his enduring cultural resonance.

5.1. Contribution to Korean Modern Art

Lee Jung-seob played a crucial role in the development of modern Korean art by effectively introducing Western art techniques while profoundly infusing them with Korean identity and sentiment. His ability to blend international artistic trends with indigenous themes and a deeply personal narrative distinguishes him as a pivotal figure who helped shape the direction of Korean modernism. His works are celebrated for their vibrant expression of Korean spirit and resilience, particularly through his iconic depictions of bulls and the innocence of children.

5.2. Art Market and Controversies

The high market value of Lee Jung-seob's works reflects his significant commercial and artistic standing. However, this popularity has also led to challenges, particularly the prevalence of forgeries. During the Korean art market boom of the late 2000s, a large number of counterfeit Lee Jung-seob paintings reportedly circulated. Investigations revealed that approximately 80% of Lee Jung-seob's works in the art market during that period were deemed forgeries. A notable controversy arose in 2005 when eight paintings, first publicly revealed and put up for auction by his second son, Lee Taeseong (Yamamoto Yasunari), were later identified as fakes in October 2005, causing a significant chilling effect on the Korean art market. His wife, Yamamoto Masako (Lee Nam-deok), passed away on August 13, 2022.

5.3. Commemoration and Cultural Representation

Lee Jung-seob's memory and art are kept alive and accessible through various forms of commemoration and cultural representation.

- Lee Jung Seob Art Gallery and Art Street: In 1995, the Lee Jung Seob Art Gallery was established in his honor in Seogwipo, Jeju Island. The museum is located at the center of the "Lee Jung-Seob's Art Street," part of Olle Route 6. The museum grounds include a path leading to the thatched-roof house where Lee and his family lived after arriving in Seogwipo, and another path from the house through a vegetable garden leads to the museum. A reproduction of his piece Fantasy of Seogwipo (1951), depicting birds and people living in harmony on a warm day with Korean peaches hanging from trees, is on display. The gallery houses 11 original works by Lee, a floor dedicated to reproductions, and many of his original letters to his wife. Due to his increasing popularity and the skyrocketing monetary value of his work, the museum faces difficulties in acquiring more original pieces for its collection. The second floor occasionally exhibits works by modern Korean artists, including many Jeju natives. The Lee Jung-Seob Arts Festival is held annually in September along Lee Jung-Seob's Art Street. Lee Jung-seob's former residence in Seoul, located at 166-10 Nusang-dong, Jongno-gu, is also preserved.

- Commemorative Stamps and Google Doodle: On April 10, 2012, Google celebrated Lee Jung-seob's 96th birthday with a Google Doodle featuring one of his iconic Bull paintings. On September 1, 2016, a commemorative stamp celebrating the 100th anniversary of Lee Jung-seob's birth was issued. On March 6, 2007, a commemorative album titled That Man Lee Jung-seob was released.

- Theatrical Adaptations: Lee Jung-seob's life and art have also been adapted into theatrical works. The Korean playwright Kim Ui-gyeong (1936-2016) authored the play A Family on the Road (길 떠나는 가족Korean), which was performed by the Seoul Metropolitan Theatre at the 8th BeSeTo Theatre Festival in 2001. This play was later adapted and directed by Kim Su-jin of Shinjuku Ryōzanpaku for the Gekidan Bunkaza theatre company, premiering in 2014 and performing over 100 stages nationwide.