1. Overview

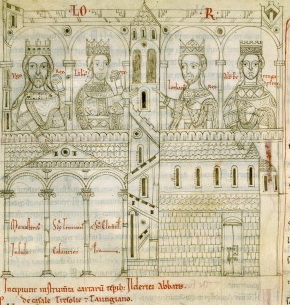

Lambert, born around 880, was a significant figure in the tumultuous political landscape of 9th-century Italy. As the son of Guy III of Spoleto, he ascended to become King of Italy in 891 and Holy Roman Emperor in 892, initially as a co-ruler with his father. His reign was marked by persistent conflicts with rival claimants to the Italian throne and the imperial title, notably Arnulf of Carinthia and Berengar I of Italy. Lambert's rule was characterized by a determined effort to consolidate power and restore order in Italy, continuing his father's policy of Renovatio regni Francorum (renewal of the Frankish kingdom), which aimed to re-establish Carolingian traditions of governance.

However, Lambert's reign is also remembered for its controversies, most notably his involvement in the infamous Cadaver Synod of 897, where the corpse of Pope Formosus was exhumed and put on trial. This event, driven by political vengeance and a desire to invalidate Formosus's acts, including Arnulf's imperial coronation, highlights the extreme measures taken in the power struggles of the era. Despite these contentious actions, Lambert demonstrated political acumen and military capability in navigating the complex alliances and conflicts of his time. He was the last ruler to issue a capitulary in the Carolingian tradition in Italy. His sudden death in 898, possibly by assassination, plunged Italy back into a period of severe political instability, underscoring the fragility of imperial authority during this period.

2. Life and Background

Lambert's early life and upbringing were deeply intertwined with the political ambitions of his powerful family, the House of Guideschi (also known as the Widones), who held significant influence in the Duchy of Spoleto.

2.1. Birth and Lineage

Lambert was born around 880, likely in San Rufino. He was the son of Guy III of Spoleto, who was Duke of Spoleto and later King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor, and Ageltrude, daughter of Adelchis of Benevento, Duke of Benevento. Lambert's family boasted significant ancestral connections to the Carolingian dynasty. His great-grandmother, Adelaide of Lombardy, was a daughter of Pepin Carloman, who was a son of Charlemagne. Furthermore, his great-uncle, Lambert I of Nantes, was married to Rotilde, a daughter of Emperor Lothair I. These connections, though somewhat distant, provided a dynastic claim to legitimacy within the fragmented Carolingian world, which his father Guy III leveraged to pursue the Italian and imperial crowns.

2.2. Early Rule and Regency

Lambert's involvement in governance began early, as his father, Guy III, sought to solidify his own position and ensure a clear succession. In May 889, following Guy III's election as King of Italy in Pavia, Lambert was appointed as the imperial and Italian regent. This move aimed to establish him as a co-ruler and heir, a strategy Guy III consistently pursued despite initial papal reluctance.

In May 891, Guy III formally declared Lambert as co-emperor in Pavia. Lambert was subsequently consecrated and recognized as King of Italy by Pope Stephen V. However, Stephen V died the same year, and Pope Formosus succeeded him. Formosus, wary of the growing power of the Spoletan house, initially resisted recognizing Lambert's imperial claims. Despite Formosus's reluctance, Lambert, along with his father Guy III, traveled to Ravenna on April 30, 892, where they eventually compelled Formosus to reluctantly crown Lambert as co-emperor. This coronation was accompanied by a pact confirming the Donation of Pepin and other Carolingian gifts to the papacy, though Formosus remained deeply apprehensive of their influence.

Following Guy III's sudden death in November 894, Lambert became the sole King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor, as well as succeeding his father as Duke of Spoleto (as Lambert II). Being still young, he was placed under the regency of his mother, Ageltrude, who was known for her staunch anti-German sentiments and her strong influence over her son's policies.

3. Reign and Major Activities

Lambert's reign was characterized by continuous struggles to assert and maintain his authority against powerful rivals and a complex web of papal politics.

3.1. Kingship and Imperial Coronation

Lambert's path to kingship and imperial dignity was closely tied to his father's ambitions. He was crowned King of Italy in May 891 at Pavia. His imperial coronation followed on April 30, 892, in Ravenna, where he was crowned joint emperor alongside his father by a reluctant Pope Formosus. This coronation was secured under duress, as Guy III exerted military pressure on the Pope. As part of this arrangement, Lambert and his father signed a pact with the pontiff, confirming the Donation of Pepin and subsequent Carolingian gifts to the papacy, a move intended to legitimize their rule in the eyes of the Church.

3.2. Papal Relations and Conflicts

Lambert's relationship with the papacy was a central and often contentious aspect of his reign. His interactions with Pope Formosus were particularly fraught. Despite crowning Lambert, Formosus secretly sought assistance from Arnulf of Carinthia, the East Frankish king, in 893, requesting him to intervene in Italy and liberate Rome, with the promise of the imperial crown. This act demonstrated Formosus's deep distrust of the Spoletan house.

After Guy III's death, Lambert and his mother Ageltrude traveled to Rome to secure papal confirmation of Lambert's imperial title. However, Formosus, still intent on crowning Arnulf, imprisoned Lambert and Ageltrude in the Castel Sant'Angelo. In February 896, Arnulf's forces took Rome by force, freeing Formosus, who then crowned Arnulf as King and Emperor, declaring Lambert deposed.

Following Formosus's death in April 896, Lambert and Ageltrude exerted their influence to ensure the election of Pope Stephen VI. This new Pope, under their sway, became a key instrument in their political retribution against Formosus. However, Stephen VI's actions were later overturned. In January 898, Pope John IX was elected, and he promptly rehabilitated Formosus, declaring the Cadaver Synod null and void. Despite this, Lambert convened a diet in Ravenna in February 898, where seventy bishops confirmed the validity of the 891 pact, declared Arnulf's coronation invalid, and reaffirmed Lambert's imperial title. They also legitimized John IX's election and confirmed Formosus's rehabilitation, attempting to bring a measure of stability to the chaotic papal politics.

3.3. Conflicts with External Powers

Lambert's reign was largely defined by his persistent military and political struggles against two formidable rivals: Arnulf of Carinthia and Berengar I of Italy.

In 893, Pope Formosus's appeal led Arnulf to send his son Zwentibold with a Bavarian army to Italy, where they joined forces with Berengar of Friuli. They initially defeated Guy III, but Guy's use of bribes and an outbreak of fever among the invading forces led to their withdrawal in the autumn. In early 894, Arnulf personally led an army across the Alps, conquering territory north of the Po River. Lambert, still young and under his mother's regency, found himself directly confronting Arnulf's ambitions.

After Guy III's death, Berengar I immediately re-occupied Pavia, but Lambert, with the strong support of his mother and loyalists, managed to expel Berengar's forces. Lambert also received support from Adalbert II of Tuscany, who menaced Berengar in Pavia. By January 895, Lambert was able to establish residence in the royal capital.

However, Arnulf's second campaign into Italy in October 895 posed a renewed threat. Arnulf quickly took Pavia and slowly advanced, gathering support among the nobility of Tuscany, including Adalbert II, who defected from Lambert's side. Arnulf eventually took Rome by force in February 896, leading to his coronation and Lambert's deposition. Despite this setback, Arnulf's campaign was cut short by a stroke, forcing his return to East Francia, which allowed Lambert to regain effective control over much of Italy.

Upon Arnulf's return to Germany, Lambert and his supporters, primarily in the northeast and central parts of the peninsula, reasserted their dominance. Lambert retook Pavia and executed Maginfred I of Milan, who had sided with Arnulf. In October and November 897, Lambert and Berengar I met outside Pavia and reached an agreement to partition the kingdom. Berengar retained the territory between the Adda River and the Po, while Lambert controlled the rest. They also agreed to share Bergamo. This arrangement essentially confirmed the status quo of 889 and saw Lambert pledge to marry Gisela, Berengar's daughter, though this alliance eventually broke down. The chronicler Liutprand of Cremona later famously remarked that the Italians always suffered under two monarchs due to this partitioning.

3.4. Legal and Administrative Policies

Lambert's governance reflected a continuation of the Carolingian tradition, particularly his father's policy of Renovatio regni Francorum (renewal of the Frankish kingdom). He was notable as the last ruler in Italy to issue capitularies, which were royal ordinances or decrees. This indicates his commitment to maintaining a structured legal and administrative framework, characteristic of earlier Frankish rule.

In 898, Lambert enacted legislation aimed at curbing the exploitation of services owed by arimanni (free Frankish or Lombard warriors/landowners) to create benefices for vassals. This measure suggests an attempt to regulate feudal obligations and protect the rights of certain segments of the population, potentially contributing to social order. Furthermore, the Lex Romana Utinensis, a compilation of Roman law, was composed at his court, reflecting an effort to codify and standardize legal practices within his domain. His rule was also recognized in Benevento following the restoration of Prince Radelchis II of Benevento in 897, indicating his influence extended into southern Italy.

3.5. The Cadaver Synod

The Cadaver Synod, also known as the "Synod Horrenda," was one of the most infamous and controversial events of Lambert's reign, occurring in early 897 in Rome. Fueled by a desire for political revenge and a need to invalidate the acts of Pope Formosus, Lambert and his mother Ageltrude pressured the newly elected Pope Stephen VI, who owed his election to their influence, to put the deceased Formosus on trial.

Formosus's body was exhumed from its tomb, dressed in papal robes, and propped up on a throne in the Lateran Basilica. A deacon was appointed to speak on behalf of the corpse. The charges against Formosus were numerous, including perjury, violating canon law by transferring bishoprics, and being consecrated while still a bishop of another see. The trial was a grotesque spectacle, with Stephen VI himself acting as prosecutor. The judgment was predetermined: Formosus was found guilty. His papacy was declared null and void, and all his ordinations and acts, including the coronation of Arnulf of Carinthia as emperor, were retroactively invalidated.

Following the verdict, Formosus's papal vestments were stripped from his corpse, and the three fingers of his right hand, used for blessings, were cut off. His body was then dragged through the streets of Rome and thrown into the Tiber River. This act of desecration was a stark display of political power and a profound violation of human dignity, even in death.

The Cadaver Synod sparked outrage and controversy across Europe. While initially serving Lambert's political agenda by discrediting Arnulf's imperial claim, it ultimately backfired. Public opinion was largely horrified, and Stephen VI himself was later imprisoned and strangled. In January 898, Pope John IX rehabilitated Formosus, declaring the Cadaver Synod illegal and restoring Formosus's ordinations. Despite John IX's efforts to reverse the damage, the Cadaver Synod remains a dark stain on the history of the papacy and a testament to the brutal political maneuvering of the era.

4. Ideology and Governing Philosophy

Lambert's political ideology and governing philosophy were largely shaped by the legacy of his father, Guy III of Spoleto, and the broader Carolingian tradition. He actively pursued the policy of Renovatio regni Francorum (renewal of the Frankish kingdom), which aimed to restore the prestige and administrative efficiency of the earlier Carolingian Empire in Italy.

This policy was not merely symbolic; it had practical implications for governance. Lambert continued the practice of issuing capitularies, a hallmark of Carolingian administration, which were legislative and administrative decrees intended to maintain order and enforce royal authority. He was, in fact, the last ruler in Italy to do so, underscoring his commitment to this traditional form of governance. His legislation in 898 against the exploitation of services owed by arimanni to create benefices for vassals further illustrates his engagement with legal and social order, aiming to regulate feudal relationships and prevent abuses. The compilation of the Lex Romana Utinensis at his court also points to an effort to codify and standardize legal practices, reflecting a desire for a more organized and coherent legal system.

Furthermore, Lambert's reaffirmation of the Constitutio Romana of Lothair I (824) at the Diet of Ravenna in February 898 was a significant ideological statement. This constitution required the imperial presence at papal elections, thereby asserting imperial oversight over the papacy. By re-establishing this principle, Lambert aimed to bolster imperial authority and ensure that the Church operated within a framework that acknowledged the emperor's supreme temporal power, aligning with the traditional Carolingian view of a unified Christian empire under imperial and papal authority, with the emperor holding a senior position in temporal matters. This demonstrated his commitment to a strong, centralized imperial power, even amidst the fragmentation of the Carolingian world.

5. Personal Life and Family

Lambert's personal life and family connections were deeply intertwined with the political landscape of his time, as dynastic alliances and lineage played a crucial role in asserting claims to power.

Lambert was the son of Guy III of Spoleto and Ageltrude, the daughter of Adelchis of Benevento, Duke of Benevento. His family lineage connected him to prominent figures of the Carolingian era. His paternal great-grandmother, Adelaide of Lombardy, was a daughter of Pepin Carloman, a son of Charlemagne, thereby linking him directly to the founder of the Carolingian Empire. His paternal grandfather was Guy I of Spoleto, and his grandmother was Ita of Benevento, daughter of Sico of Benevento. He also had an uncle, Lambert I of Spoleto, and a cousin, Guy II of Spoleto.

Lambert had a brother, Guy IV of Spoleto, who succeeded him as Duke of Spoleto after his death. Lambert was married to Adelaide, a daughter of Pepin II of Senlis, who was a great-grandson of Pepin Carloman. This marriage would have further solidified his family's connections within the Frankish nobility.

Contemporary accounts offer some insight into Lambert's character. The chronicler Liutprand of Cremona remembered him as an elegans iuveniselegant youthLatin and vir severusstern manLatin, suggesting a combination of youthful refinement and a serious, perhaps unyielding, disposition befitting a ruler in such turbulent times.

6. Death

Lambert's reign came to an abrupt end on October 15, 898, under circumstances that remain somewhat ambiguous, with historical accounts offering different possibilities.

He was killed while hunting near Marengo, south of Milan, after having surprised and defeated the rebellious Adalbert II of Tuscany at Borgo San Donnino and taken him prisoner to Pavia. The primary source for this event, Liutprand of Cremona, is reserved on the exact cause of death, presenting two main theories: either he was assassinated by a figure named Hugh, who was the son of Maginulf (a count of Milan who had joined Arnulf and was later executed by Lambert), or he died from falling from his horse during the hunt. The assassination theory suggests a political motive, given the numerous rivals and enemies Lambert had made during his contentious reign.

His body was subsequently transported to Piacenza, where he was interred in the local church. Liutprand of Cremona, in his account, provided an epitaph for Lambert, written in Latin elegiac couplets, which reads:

Sanguine præcipuō Francōrum germinis ortus

Lambertus fuit hīc Caesar in Urbe potēns

Alter erat Cōnstantīnus, Theodōsius alter

Et prīnceps pācis clārus amōre nimisLatin

The English translation of the epitaph is:

- Born with the distinguished blood of the stock of the Franks,

- Lambert was here Emperor, holding power in the City (of Rome);

- He was another Constantine, another Theodosius,

- and a prince of peace, excessively renowned with love.

This epitaph, despite the turbulent nature of his reign and his controversial actions, portrays Lambert in a highly idealized manner, likening him to revered Roman emperors and emphasizing a desire for peace, perhaps reflecting a posthumous attempt to shape his legacy. His death immediately plunged the regnum Italicum (Kingdom of Italy) and the imperium Romanum (Roman Empire) into further chaos, as multiple candidates vied for the vacant titles. Within days of Lambert's death, Berengar I of Italy swiftly took control of Pavia, signaling the renewed fragmentation of power in Italy.

7. Assessment and Legacy

Lambert's reign, though relatively short, left a significant, albeit complex, mark on the history of Italy and the broader Carolingian world. His actions and the events surrounding his rule shaped the political landscape of the late 9th century.

7.1. Positive Assessment

Despite the constant conflicts, Lambert demonstrated considerable political and military acumen. He successfully navigated a period of intense fragmentation, managing to assert control over a significant portion of Italy after the withdrawal of Arnulf of Carinthia. His ability to retake Pavia and negotiate a partition agreement with Berengar I of Italy, even if temporary, highlights his pragmatic approach to governance and his skill in maintaining a precarious balance of power.

Lambert's commitment to the Renovatio regni Francorum (renewal of the Frankish kingdom) policy, inherited from his father, signifies an attempt to restore order and legitimate authority in a chaotic era. His issuance of capitularies, making him the last ruler to do so in Italy, underscores his dedication to maintaining legal and administrative traditions. Furthermore, his legislation against the exploitation of arimanni and the compilation of the Lex Romana Utinensis suggest a ruler concerned with legal reform and potentially, social justice, aiming to protect the rights of certain segments of the population and standardize legal practices. His reaffirmation of the Constitutio Romana also showed a strategic vision to reassert imperial authority over papal elections, a move that, while self-serving, aimed at a more stable relationship between secular and ecclesiastical powers.

7.2. Criticism and Controversy

Lambert's reign is most notably stained by the infamous Cadaver Synod of 897. His instigation of the posthumous trial of Pope Formosus's corpse, driven by political vengeance and a desire to invalidate Arnulf's imperial coronation, was a barbaric act that shocked contemporaries and remains a symbol of the extreme corruption and brutality of the period's power struggles. This event, which involved the desecration of a dead body and the manipulation of religious authority for political ends, stands as a stark criticism of his methods. While politically expedient in the short term, it ultimately undermined the legitimacy of the papacy and contributed to the moral decay of the Church.

His constant conflicts with rivals like Arnulf and Berengar, while necessary for survival, also contributed to the ongoing instability and fragmentation of Italy. The chronicler Liutprand of Cremona's remark that the Italians "always suffered under two monarchs" (referring to Lambert and Berengar) highlights the burden placed upon the populace by these incessant power struggles. His political methods, including the execution of opponents like Maginfred I, reveal a stern and ruthless approach to consolidating power.

7.3. Impact on Later Generations

Lambert's sudden death without a direct male heir had a profound and immediate impact on the political landscape of Italy. The regnum Italicum (Kingdom of Italy) and the imperium Romanum (Roman Empire) were thrown into renewed chaos, contested by multiple claimants, leading to a prolonged period of instability known as the "Dark Age of the Papacy" or the "Saeculum Obscurum".

His brother, Guy IV of Spoleto, succeeded him as Duke of Spoleto, but even this regional power base soon faced challenges, eventually falling under the control of other powerful families. The fragmentation of authority in Italy intensified after Lambert's demise, with various local lords and claimants vying for power, preventing the emergence of a strong, unified central authority for decades. The events of his reign, particularly the Cadaver Synod, also had a lasting impact on the perception of papal authority and the relationship between secular rulers and the Church, contributing to a period of moral decline within the papacy. In essence, Lambert's rule, while marked by attempts to restore order, ultimately ended in a return to the very chaos he sought to overcome, leaving a legacy of contested power and political instability.