1. Overview

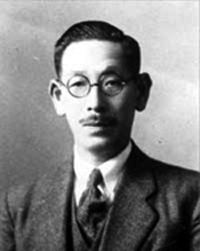

Kyōsuke Kindaichi (金田一 京助Kindaichi KyōsukeJapanese, May 5, 1882 - November 14, 1971) was a prominent Japanese linguist and ethnologist, widely recognized as the pioneering founder of formal Ainu language research in Japan. His extensive work included the dictation and study of yukar (Ainu epic poems), contributing significantly to the preservation of Ainu oral traditions. He also authored the renowned Meikai Kokugo Jiten, a foundational Japanese language dictionary.

Throughout his career, Kindaichi served as a professor at Kokugakuin University, Rikkyo University, and the University of Tokyo, eventually becoming a member of the Japan Academy and the second president of the Linguistic Society of Japan. While his academic contributions are widely acknowledged and earned him the Order of Culture in 1954, his methodologies and perspectives, particularly regarding Ainu assimilation policies, have faced criticism from Ainu scholars and later researchers. He was also a close friend of the poet Ishikawa Takuboku, a relationship that became a subject of discussion and controversy. Kindaichi's legacy extends to popular culture, notably inspiring the creation of the fictional detective Kōsuke Kindaichi.

2. Life

Kyōsuke Kindaichi's life spanned a period of significant change in Japan, from the Meiji era through the post-war period. Despite facing personal hardships and financial struggles, he dedicated his life to scholarship, especially the groundbreaking study of the Ainu language and culture.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Kindaichi was born on May 5, 1882, in Yotsuyamachi, Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, as the eldest son of Kindaichi Kumenosuke and Yasu. He was one of eleven children, with one elder sister, six younger brothers, and three younger sisters. His unique name, Kyōsuke, was given because his father was on a business trip to Kyoto when he was born. The Kindaichi family was well-established, having gained samurai status in the Nanbu Domain after Kyōsuke's great-grandfather, Ihee Katsusumi, used his wealth as a rice merchant to help the community during a great famine. While his father, Kumenosuke (formerly Umeri), came from a farming background, he was talented in academics and art, though unsuccessful in business. Despite his father's failures, Kyōsuke grew up without financial hardship thanks to the support of his paternal uncle, Kindaichi Katsusada (Yasu's elder brother), who was the head of the main Kindaichi household. All six of Kyōsuke's younger brothers went on to study at the University of Tokyo.

In his early childhood, Kumenosuke would recount tales like The Tale of the Heike and Genpei Jōsuiki to his children before they slept. Kyōsuke later frequented the Kindaichi family's private library, immersing himself in books such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Records of the Grand Historian. He attended Iwate Prefectural Morioka Jinjo Junior High School (now Iwate Prefectural Morioka First High School), where his classmates included Koshiro Oikawa and Hodo Nomura. During his time there, a fire at his home caused by a lamp injured his hand, leaving his middle and ring fingers bent and preventing him from pursuing his passion for painting. This setback further intensified his dedication to literature. He was deeply influenced by Tōson Shimazaki's Wakanashū and submitted poems to literary magazines under the pen name "Bairikamei," earning him the nickname "Kindaichi Kahyō" among his peers. His poems were even reprinted in the first issue of Myōjō in April 1900, which led to his becoming an associate of the Shinshisha, the publisher of Myōjō, and he continued to publish tanka (short poems) there. Around January 1901, Oikawa Koshiro introduced him to Ishikawa Takuboku, a younger student interested in tanka, and Kindaichi lent Takuboku all issues of Myōjō. They later collaborated on a circulating tanka magazine called Hakuyō. In 1898, as a third-year student, Kindaichi was one of 17 scholarship students in the entire school, with an average academic score of 86 points. During his youth, Kindaichi was rather small, and to avoid daytime sparring in judo, he focused on morning practice. Mitsumasa Yonai, two years his senior, also practiced in the mornings. Despite Yonai's larger stature, he would often fall with a loud thud when Kindaichi applied a technique, leading Kindaichi to feel awkward due to the apparent skill difference.

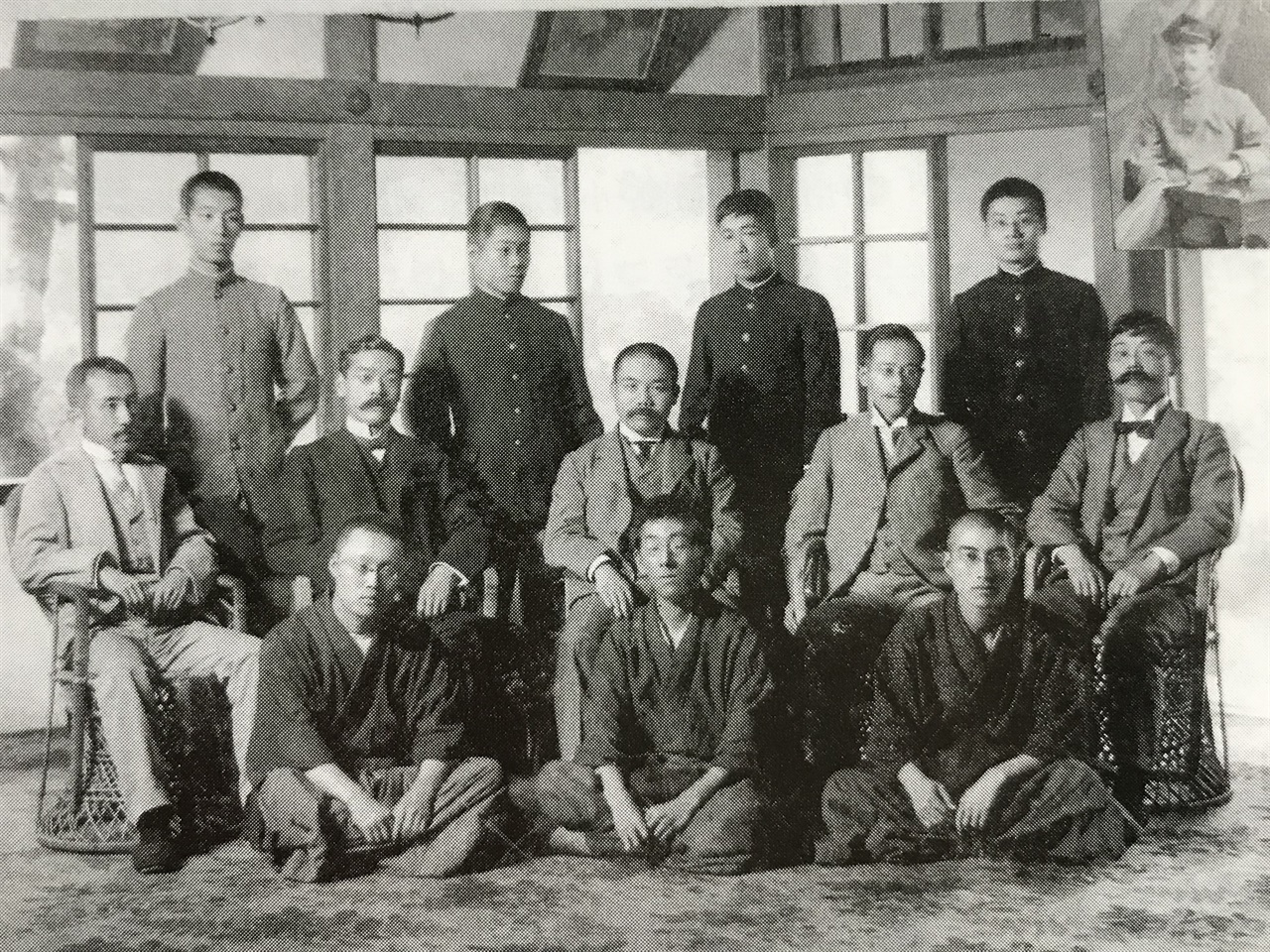

2.2. Early Career and Introduction to Ainu Language Research

In September 1904, after graduating from Dai Ni Kōtō Gakkō, Kindaichi moved to Tokyo and enrolled in the Department of Literature at Tokyo Imperial University. Captivated by the lectures of Izuru Shinmura and Kazutoshi Ueda, he chose to specialize in linguistics. His seniors in the department included Shinkichi Hashimoto, Shimpei Ogura, and Fuyū Iha. While Ogura researched Korean and Iha researched Ryukyuan, there were no Japanese scholars studying Ainu, with only the English missionary John Batchelor having published an Ainu dictionary. Ueda encouraged Kindaichi, stating that "Ainu language research is the mission of Japanese scholars," which led Kindaichi, being from the Tohoku region, to select Ainu as his research topic.

In 1906, Kindaichi embarked on his first trip to Hokkaido to collect Ainu linguistic data, with his uncle Katsusada providing the 70-yen travel expenses. This survey bolstered his confidence in his research. The following year, in 1907, he conducted research on the Sakhalin Ainu language in Ochopokka, Sakhalin. He learned the Sakhalin Ainu language through interactions with Ainu children, an episode that later became famous in his essay Kokoro no Komichi (The Path of the Heart). He spent a considerable sum of 200 JPY (100 yen from Katsusada and 100 yen from Ueda) for his 40-day stay, successfully collecting grammatical information and 4,000 vocabulary words. Upon his return, Kindaichi resolved to dedicate his life to Ainu studies, overcoming his worries about livelihood. By the time he submitted his research report to Ueda in October, his university graduation ceremony had already passed.

In April 1908, Kindaichi started working as a Japanese language teacher at Kaijo Junior High School. Later that month, Ishikawa Takuboku moved into Kindaichi's boarding house, "Sekishinkan." Kindaichi lent money to Takuboku and paid their combined rent of 30 JPY. In August, unable to pay, he was refused by the landlady, so he sold two cartloads of his treasured books to raise the 30 yen, and in early September, he and Takuboku moved to another boarding house, "Gaiheikan." In October, Kindaichi lost his job after it was discovered that he, as a linguistics graduate, did not possess a teaching certificate. Through the introduction of his mentor, Shōzaburō Kanazawa, he found employment at Sanseido Publishing and also became a part-time lecturer at Kokugakuin University. Takuboku was later hired by the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun as a proofreader in March of the following year and moved out with his family, who had come to Tokyo.

In 1909, at age 27, Kindaichi married Shizue Hayashi, whom Takuboku had introduced to him. Takuboku promoted Kindaichi as "a literary scholar and university lecturer, whose uncle is a bank president in Morioka." Kindaichi, who had hoped to marry a woman from Tokyo, especially from the Hongo area (where standard Japanese was spoken), rather than from his hometown, was drawn to Shizue, who was from Hongo. They married on December 28, took a honeymoon to Hakone, and had a reception at Katsusada's house in Morioka. However, Shizue, accustomed to Tokyo life, disliked the countryside. Additionally, Takuboku frequently asked for money, which strained Shizue's household management, though Kindaichi seemed unconcerned. Eventually, Shizue confronted Kindaichi, asking "who was more important, her or Takuboku," leading Kindaichi to distance himself from Takuboku. When Takuboku's eldest son, Shin'ichi, died at 24 days old in 1910, Takuboku sent Kindaichi a postcard asking to borrow mourning clothes, but Kindaichi did not reply and neither attended the funeral nor contributed money. Furthermore, Kindaichi showed no reaction to the publication of A Handful of Sand, which was released immediately after, despite Takuboku thanking him by name in the preface and sending him a dedicated copy. Later, Kindaichi wrote in his book Ishikawa Takuboku that he had prepared mourning clothes but Takuboku didn't come, that he was too busy to attend the funeral, and that he intended to thank Takuboku for A Handful of Sand when they next met, but critics view this as a clear fabrication. In July 1911, a seriously ill Takuboku, leaning on a cane, made his "last visit" to Kindaichi's home during the intense summer heat.

In January 1912, Kindaichi's eldest daughter, Ikuko, died twenty days before her first birthday. Takuboku's condolence postcard was his last letter to Kindaichi. On March 30, Kindaichi learned of Takuboku's critical condition from a Yomiuri Shimbun article (written by Zenmaro Toki). He canceled his cherry blossom viewing plans, took half of the advance for his first published work, Shin Gengogaku (A History Of The Language, a translation published in June), which amounted to 10 JPY (though he actually took the money from his home as he hadn't received the advance yet), and rushed to Takuboku's side. Takuboku and his wife Setsuko shed tears of gratitude for his kindness. In the early morning of April 13, Takuboku's condition became critical, and Setsuko summoned Kindaichi by rickshaw. However, Takuboku soon regained consciousness and even conversed, leading Kindaichi to believe he was "fine" and proceed to Kokugakuin for his lecture. Shortly after, Takuboku passed away, and Kindaichi, returning to Takuboku's home after his lecture, found himself facing Takuboku's remains. Soon after Takuboku's funeral, Kindaichi received news of his father's critical condition and returned home.

On September 26 of the same year, his father, Kumenosuke, passed away. Kumenosuke's business failures had accumulated debts, forcing the family to cede their home to the main family's adopted son, Kindaichi Kunio, in exchange for debt repayment. The family then lived in the main family's tenement house. During a visit to his father in a Tokyo hospital, Kindaichi was told, "I never received a single grain of rice from you." After his father's death, Kindaichi considered abandoning his unlucrative Ainu research but instead resolved to dedicate himself even more seriously, feeling he owed it to his father's sacrifice. In September, Sanseido Publishing went bankrupt, and Kindaichi again found himself unemployed.

2.3. Dedicated Ainu Language Research and Major Achievements

In October 1912, the Colonial Exhibition was held at Ueno Park in Tokyo. Kindaichi earned money by teaching visitors greetings and daily phrases of Japan's minority ethnic groups. At the same time, he interviewed Sakhalin Ainu participants, which enabled him to translate and annotate Hauki and other yukar he had collected in Sakhalin. Here, he met Nabesawa Koponanu from Shiwunkotsu village in Hidaka, who informed him of the existence of the lengthy yukar "Kutneshirka" and introduced him to Wakarpa, a blind yukar master who could recite it. When Kindaichi consulted Ueda Kazutoshi, Ueda provided travel expenses from his own pocket. In July 1913, Kindaichi invited Wakarpa to Tokyo. During his approximately one-month stay, Kindaichi transcribed 14 yukar pieces, amounting to 20,000 lines of verse, and 1,000 pages of oral narratives across ten notebooks. However, a typhus outbreak in Wakarpa's hometown prompted his return at the end of August, as villagers requested his prayers. After praying for each villager, Wakarpa himself succumbed to typhus, dying on December 7. Kindaichi learned of his death the following year.

Meanwhile, in 1912, Yamabe Yasunosuke, a Sakhalin Ainu who had participated in Shirase Nobu's Antarctic expedition (and with whom Kindaichi had previous acquaintance), returned to Japan. Kindaichi transcribed and translated Yamabe's oral account of his life, publishing it the following year, 1913, as Ainu Monogatari (Ainu Stories) in two volumes by Hakubunkan.

In 1918, during a research trip to Hokkaido, Kindaichi met Matsunari Chiri and her 16-year-old daughter, Yukie Chiri, at their home. When Yukie asked if yukar had any value, Kindaichi passionately explained their significance as valuable literature. He considered inviting Yukie, who was proficient in both Ainu and Japanese, to Tokyo after her graduation from girls' school and sent her notebooks, encouraging her to transcribe yukar in Roman script. Despite her chronic heart condition, Yukie came to Tokyo in May 1922 and stayed at Kindaichi's residence. Plans for publishing Ainu Shin'yōshū (Collection of Ainu Mythological Epics) based on Yukie's notes progressed. Kindaichi praised Yukie's "brilliant mind" and "linguistic genius," calling her an "angelic woman" as she explained Ainu grammar that he had previously not understood. During this period, Kindaichi's wife, Shizue, suffered from mental health issues due to financial hardship and the deaths of their children. Yukie sometimes cared for their fourth daughter, Wakaba. Although Shizue's sister suggested taking her in and arranging a divorce, Kindaichi flatly refused, stating, "Absolutely not. I married her." He showed little concern for his wife's struggles. Yukie completed Ainu Shin'yōshū and passed away on September 18 at the young age of 19 years and 3 months.

In 1923, Kindaichi visited Kurokawa Tsunare, a yukar master in Nukibetsu. Wakarpa had left instructions to visit Tsunare if he only knew "Kutneshirka" in part. However, Tsunare was critically ill and bedridden, and his family initially refused Kindaichi's request for an interview. Kindaichi pleaded repeatedly and was finally allowed a brief visit. Upon meeting Tsunare, Kindaichi praised him in Ainu. Tsunare then grabbed a belt hanging from the ceiling, pulled himself up, and began to recite "Kutneshirka." Villagers gathered, urging Kindaichi to stop transcribing, embarrassed that such a fragmented recitation would be preserved as Tsunare's yukar. However, Tsunare waved his hand, insisting that Kindaichi write it down. It was through Tsunare that Kindaichi discovered Wakarpa's "Kutneshirka" was complete, not partial. Nevertheless, Kindaichi's forceful methods in this instance later drew severe criticism.

2.4. Research Culmination and Later Life

In 1931, Kindaichi's monumental work, Yūkara no Kenkyū: Ainu Jojishi (A Study of Yukar: Ainu Epic Poetry), was published in two volumes. In his later essay Watashi no Aruite Kita Michi (The Path I Have Walked), Kindaichi recalled that he wrote it in 1930 at the repeated urging of Shigeo Oka of Okashoin, publishing it in 1931 and receiving the Imperial Prize in 1932. However, Oka's own memoir, Honya Fūzei (Bookseller's Style), provides a different account. Initially, Kindaichi had submitted his yukar research as a doctoral dissertation in English to Tokyo Imperial University, but it was lost in the Great Kantō Earthquake while stored in the university library due to a lack of suitable examiners. Kunio Yanagita, regretting this loss, asked his acquaintance Shigeo Oka for assistance. Oka visited Kindaichi, who was then living in a temporary shelter after the earthquake. With Oka's encouragement and cooperation, Kindaichi rewrote the entire work in Japanese. Oka also arranged for Keizō Shibusawa to provide 50 JPY monthly to Kindaichi, and research funds were also sent from the Tōyō Bunko (Oriental Library) when the book was published. This collaborative effort resulted in the two-volume, 1,458-page masterpiece. In Honya Fūzei, Oka expressed his deep regret that Kindaichi minimized the contributions of Yanagita and Shibusawa in his own account.

In 1930, Yukie Chiri's younger brother, Mashio Chiri, came to Tokyo seeking Kindaichi's help, entering Ichiko High School. He later graduated from the University of Tokyo's linguistics department, becoming Kindaichi's second disciple in Ainu language research after Itsuhiko Kubodera.

Published in 1943, Meikai Kokugo Jiten became a bestseller. Hidekazu Kenbō, in his book Jisho o Tsukuru (Making a Dictionary), stated that while many Japanese dictionaries bore Kindaichi's name, most merely exploited his reputation. He affirmed that Meikai Kokugo Jiten was the only one that Kindaichi genuinely oversaw "to the very last line." However, the dictionary was primarily compiled by Kenbō alone. As Kenbō was still a graduate student at Tokyo Imperial University at the time, it was deemed inappropriate to publish a dictionary under his name. Thus, Kindaichi, who had introduced Kenbō to Sanseido, allowed his name to be used. According to Kindaichi's eldest son, the linguist Haruhiko Kindaichi, many dictionaries published under the name "Compiled by Kyōsuke Kindaichi" were in fact merely lent his name, with Kindaichi himself having done little of the actual work.

As World War II worsened, Kindaichi remained unwavering in his belief in Japan's victory. When Tokyo was subjected to air raids, his eldest son, Haruhiko, who had married and moved out, urged him to evacuate. Kindaichi entrusted his wife Shizue, daughter Wakaba, and his extensive library to a room prepared by Shirō Hattori in Okutama. Fortunately, Kindaichi's home survived the air raids, and the three returned after the war. However, on December 24, 1949, Wakaba committed suicide by drowning herself in the Tamagawa Aqueduct at the age of 28. She had married the previous year but left a suicide note indicating her lack of confidence in continuing to live due to her weak constitution.

2.5. Later Life and Death

After World War II, Sanseido Publishing sought Kindaichi and his son Haruhiko to write a Japanese textbook for the new curriculum. Their collaborative work, Chūtō Kokugo Kindaichi Kyōsuke Hen (Secondary Japanese, Edited by Kyōsuke Kindaichi), commonly known as Chukin, became the top-adopted textbook for over a decade, serving as a representative Japanese language textbook.

In his later years, Kindaichi focused on translating and annotating the yukar notes he had transcribed from Matsunari and others. These were published as Ainu Jojishi Yukarashū (Collection of Ainu Epic Poems) starting in 1959. He died while the ninth volume of the translation and annotation was still in progress.

In 1969, Kindaichi moved into a condominium in Hongo purchased by his son Haruhiko. Around August 1971, he spent increasing time in bed. His condition worsened on the morning of November 7, and he passed away on November 14, 1971, at 8:30 p.m., at the age of 89, due to old age, arteriosclerosis, and bronchopneumonia. His Buddhist name is "Jutokuin Den Tetsu Gen Kamyo Daikoji." His rank was posthumously elevated to Junior Third Rank, and he was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1st Class. The vigil was held on November 15 at Kifukuji Temple, followed by a private funeral on the 16th. On November 23, a public farewell ceremony, organized as a company funeral by Sanseido, was held at the Aoyama Funeral Hall. The funeral committee chairman was President Kamei Kaname, and eulogies were delivered by dignitaries such as Minister of Education Saburō Takami and Japan Academy President Shigeru Nambara, praising his accomplishments. Condolence flowers were sent from universities, media outlets, actors, and politicians, making it an exceptionally grand funeral for a scholar.

3. Character and Thought

Kyōsuke Kindaichi's intellectual and personal character was shaped by his dedication to Ainu studies and his complex relationships with key figures, revealing both profound academic commitment and controversial perspectives.

3.1. Perspectives on Ainu Language Research

Throughout his life, Kindaichi endured poverty to dedicate himself to the study of the Ainu language. His grandson, Hideho Kindaichi, stated in 2014 that without Kyōsuke Kindaichi, the Ainu language might not have survived. Kindaichi engaged with Ainu people with sincerity, telling them, "Ainu are a great people" and "Your culture is by no means inferior," at a time when Ainu were widely taught to be inferior to Wajin (ethnic Japanese). However, he also expressed internal conflicts regarding his research, reflecting on his peers pursuing Western and Japanese philosophy: "It made me feel quite lonely to think that while all my fellow students were delving into splendid Western literature, or tracing lofty ideas in Western or Japanese philosophy, building themselves up, I alone would be left behind, engaging in such barbaric things." He further wrote, "A sadness wells up, thinking that I alone would regress to the world of uncivilized people, to wander forever in an ignorant, low-level culture." (My Path I Have Walked, 1997; My Work, 1954).

After World War II, Kindaichi faced criticism for his perceived cooperation with the Ainu assimilation policy. In his 2008 book Kindaichi Kyōsuke to Nihongo no Kindai (Kyōsuke Kindaichi and the Modern Japanese Language), Toshiaki Yasuda critically examined Kindaichi's stance on Ainu and the Ainu language, including his belief that Ainu should abandon their language and assimilate into the Japanese national language.

Mashio Chiri, Kindaichi's disciple, later critically assessed the Ainu language research conducted by Kindaichi and other Japanese scholars. When Chiri's work, Ainu Language Dictionary: Plants, was nominated for the Asahi Prize, Kindaichi initially refused to recommend it, citing Chiri's criticism of Hokkaido University botanists in the preface. Chiri reportedly confided to others that Kindaichi "was jealous of him." However, Kindaichi did write a recommendation for the subsequent volume, Human. Mashio passed away in 1961 at the age of 52. Kindaichi, then 79, flew to Hokkaido for the funeral, only to find that Kindaichi's name was not on Mashio's list of people to be notified upon his death.

On one occasion, Kindaichi was scheduled to lecture to Emperor Showa on the Ainu language. Despite being allotted only 15 minutes, he continued speaking for nearly 2 hours. Kindaichi was mortified, believing he had greatly embarrassed himself before the Emperor. However, at a tea ceremony held later, the Emperor remarked, "Your talk the other day was very interesting." Kindaichi was so overwhelmed by this kind word that he could only utter "Thank you, Your Majesty" before tears prevented him from speaking further. Furthermore, upon Kindaichi's death, the Emperor sent an imperial offering.

3.2. Relationship with Ishikawa Takuboku

Kindaichi's friendship with the poet Ishikawa Takuboku was intimate yet fraught with complications, particularly concerning the posthumous publication of Takuboku's private writings. When Ishikawa Takuboku Zenshū (Complete Works of Ishikawa Takuboku) was to be published, Kindaichi vehemently opposed the inclusion of Takuboku's Romaji Nikki (Romanized Diary), which contained descriptions of Takuboku's visits to Asakusa brothels and interactions with prostitutes. Kindaichi feared that such revelations would negatively affect his daughter's marriage prospects. In fact, Takuboku had three times entrusted his diaries, including Romaji Nikki, to Kindaichi during his lifetime, instructing him to burn them if he deemed it appropriate after reading them. However, immediately after Takuboku's funeral, Kindaichi had to leave Tokyo due to his father's critical condition (and Kiichi Maruya, who was strictly ordered to burn the diaries, was absent for a conscription examination), so the diaries remained with Takuboku's wife, Setsuko. Before her death in Hakodate, Setsuko spoke of entrusting the diaries to Uu Miyazaki, and after Setsuko's passing, Miyazaki deposited them with the Hakodate Central Library.

More than twenty years later, in 1936, Kaizosha Publishing expressed interest in publishing the diaries. Maruya consulted Kindaichi and Zenmaro Toki, and they collectively sent a letter to Kenzō Okada, the director of the Hakodate Library, requesting the publication of the diaries (which would involve distributing them among the three) and their subsequent disposition "in a manner deemed most satisfactory by the deceased and all concerned parties." This request, however, was ignored. Three years later, in 1939, Okada Kenzo publicly declared on a radio broadcast that he would neither publish nor burn the diaries during his lifetime. Hearing this, Kindaichi, while outwardly praising Okada's decision, saying there seemed to be "no special reason, only the common psychology of collectors," expressed his disappointment, adding, "But that's probably fine. That spirit is what saved the diary from incineration." When Okada died in 1944, and Ishikawa Masao (Takuboku's eldest daughter Kyoko's husband) later decided to publish the diaries, he asked Kindaichi to verify the contents. Kindaichi, reading the diaries for the first time, tried to endure the inclusion of unfavorable content as much as possible for fairness, only requesting the deletion of one passage from Romaji Nikki that he found "too severe" and another that he judged to be "morally problematic for living individuals." However, Ishikawa Masao published them without these deletions. In his essay "At the End of Takuboku's Diary," published in the three volumes of Ishikawa Takuboku Nikki (Sekai Hyoronsha, 1949), Kindaichi recounted his impressions of reading the diary, including nostalgia and discrepancies with his memories. He concluded by asserting that "The publication of Takuboku's diary, a vivid record of an eternal youth who, under such a harsh destiny, did not curse fate, overcame illness and poverty, envisioned new ideals for tomorrow, and peacefully passed away as if falling asleep-in that sense, I believe it has added something eternally valuable to modern literature."

Kindaichi also asserted that Takuboku underwent an "ideological turning point" in his later years, based on his memory of Takuboku's final visit. Yoshinori Iwaki, a researcher, criticized this claim based on historical documents. Kindaichi then published an emotional rebuttal in 1961, leading to a heated debate between them. However, when Kindaichi shifted the focus of the argument from "Takuboku's ideological turning point" to the mere presence or absence of "Takuboku's visit," Iwaki ended the dispute. After resolving misunderstandings through private correspondence, they met in 1964 at Kindaichi's invitation and reconciled. Iwaki had initially pursued research influenced by Kindaichi's book Ishikawa Takuboku and sent his first privately published paper to Kindaichi, thus beginning their correspondence. Kindaichi had always highly regarded Iwaki's empirical research. During their meeting, Kindaichi dismissed the dispute as "like a parent-child disagreement, so don't worry about it." After this, Kindaichi and Iwaki maintained their close relationship as before. However, Iwaki's view on Takuboku's "ideological turning point" is now generally accepted as the mainstream theory.

3.3. Other Anecdotes

Kindaichi was an ardent advocate for the establishment of Standard Japanese and served as the chairman of the Standard Japanese Subcommittee of the National Language Council. He reportedly harbored a complex about his own pronunciation, with his son Haruhiko recounting an episode where Kindaichi was disheartened after listening to recordings of his own speech.

Despite being from the Tohoku region, Kindaichi opposed theories such as the Yoshitsune Northern Expedition Theory and the Yoshitsune-Genghis Khan theory. In the magazine Chūō Shidan, he harshly criticized Zennichirō Otabe, a proponent of these theories whom he had befriended in his youth, stating that "Otabe's theory is subjective, and historical papers should be objectively argued; this kind of paper is a 'belief.'" Kindaichi concluded that the Gion Koshijima-watari narrative, which posits Yoshitsune's journey north, was an ancient tale that crossed into Ezochi (Hokkaido) and was later mistakenly understood by Wajin as an Ainu tradition. He believed that the connection between Okikurumi and Yoshitsune was relatively recent and that the narratives of Ainu elders were influenced by their awareness of Wajin.

An enduring anecdote related to Kindaichi's Sakhalin Ainu language collection methods from 1907 became widely known through his 1931 essay "Katakoto o Iu Made" (Until I Spoke Broken Words) and his post-war junior high school Japanese textbook essay "Kokoro no Komichi" (The Path of the Heart). In these accounts, Kindaichi described how, after arriving in Sakhalin, the Hokkaido Ainu language he had learned proved ineffective, and local Ainu initially refused to speak with him. He recounted that he eventually drew pictures in front of playing children, who showed interest and spoke Sakhalin Ainu words. When he used these learned words in front of adults, they were greatly pleased and began to teach him their language. However, his disciple Mashio Chiri later pointed out that Sakhalin Ainu had visited Hokkaido, making it unlikely that the Hokkaido Ainu language would be entirely incomprehensible to them. Kindaichi clarified that he had not written that the language was unintelligible, but rather that the villagers were initially wary and unwilling to speak with him.

4. Works

Kyōsuke Kindaichi made extensive contributions to linguistics, ethnology, and Japanese language studies through his numerous published works.

4.1. Solo Works

- Kita Ezo Koyō Ihen (Old Songs of North Ezo Remnants) (1914)

- Ainu no Kenkyū (Studies of Ainu) (1925)

- Yūkara no Kenkyū Ainu Jojishi (A Study of Yukar: Ainu Epic Poetry) (2 vols.) (1931)

- Kokugo On'inron (On Japanese Phonology) (1932)

- Ainu Bungaku (Ainu Literature) (1933)

- Gengo Kenkyū (Language Research) (1933)

- Ishikawa Takuboku (1934), later revised and published as Kadokawa Bunko, Kodansha Bungei Bunko

- Kita no Hito (People of the North) (1934), later Kadokawa Bunko

- Gakusō Zuihitsu (Essays from the Study Window) (1936)

- Yūkara (Essays) (1936)

- Saiho Zuihitsu (Essays from Field Surveys) (1937)

- Kokugoshi - Keitōhen - (History of the Japanese Language - Lineage Edition -) (1938)

- Kokugo no Hensen (Changes in the Japanese Language) (1941), later Sogensha Bunko

- Shin Kokubunpō (New Japanese Grammar) (1941)

- Kokugo Kenkyū (Japanese Language Research) (1942)

- Yūkara Gaisetsu Ainu Jojishi (Outline of Yukar: Ainu Epic Poetry) (1942)

- Kotodama o Megurite (Concerning the Spirit of Words) (1944)

- Kokugo no Shinro (The Future of the Japanese Language) (1948)

- Kokugo no Hensen (Changes in the Japanese Language) (1948), later Kadokawa Bunko, "Nihongo no Hensen" Kodansha Gakujutsu Bunko

- Shin Nihon no Kokugo no Tame ni (For the New Japanese Language) (1948)

- Kokugogaku Nyūmon (Introduction to Japanese Linguistics) (1949)

- Kokoro no Komichi (The Path of the Heart) (Essays) (1950)

- Gengogaku Gojūnen (Fifty Years of Linguistics) (1955)

- Nihon no Keigo (Japanese Honorifics) (1959), later Kodansha Gakujutsu Bunko

- Kindaichi Kyōsuke Shū: Watashitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka (Kyōsuke Kindaichi Collection: How Should We Live?) (1959)

- Kindaichi Kyōsuke Senshū Kindaichi Hakushi Kiju Kinen Dai 1 (Ainu-go Kenkyū) (Selected Works of Kyōsuke Kindaichi, Commemorating Dr. Kindaichi's 77th Birthday, Vol. 1 (Ainu Language Research)) (1960)

- Kindaichi Kyōsuke Senshū Dai 2 (Ainu Bunkashi) Nihongo no Hasshō (Selected Works of Kyōsuke Kindaichi, Vol. 2 (Ainu Cultural History) The Origin of Japanese) (1961)

- Kindaichi Kyōsuke Senshū Dai 3 (Kokugogaku Ronkō) (Selected Works of Kyōsuke Kindaichi, Vol. 3 (Essays on Japanese Linguistics)) (1962)

- Kindaichi Kyōsuke Zuihitsu Senshū Dai 1-3 (Selected Essays of Kyōsuke Kindaichi, Vols. 1-3) (1964)

- Watashi no Aruite Kita Michi Kindaichi Kyōsuke Jiden (The Path I Have Walked: Autobiography of Kyōsuke Kindaichi) (1968)

4.3. Translated Works

- Shin Gengogaku (New Linguistics) by Henry Sweet (1912)

- Ainu Seiten (Ainu Scriptures), World Sacred Texts Collection, Sekai Bunko (1923)

- Ainu Rakukuru no Densetsu Ainu Shinwa (Legends of the Ainu Rakukuru: Ainu Mythology), Sekai Bunko Kankōkai (1924)

- Ainu Jojishi Yūkara (Ainu Epic Yukar), Iwanami Bunko (1936), reprinted 1994, among others

- Kutneshirka no Kyoku Ainu Jojishi (The Song of Kutneshirka: An Ainu Epic) (1944)

- Yūkarashū Ainu Jojishi (Collection of Yukar: Ainu Epic Poetry), Vols. 1-8, recorded by Matsunari, translated and annotated (1959-68)

4.4. Commemorative Publications

- Gengo Minzoku Ron Sō: Kindaichi Hakushi Koki Kinen (Essays on Linguistics and Folklore: Commemorating Dr. Kindaichi's 70th Birthday) (1953)

- Kindaichi Hakushi Beiju Kinen Ronbunshū (Collection of Papers Commemorating Dr. Kindaichi's 88th Birthday) (1971)

4.5. Lyric Writing

Kyōsuke Kindaichi also composed lyrics for various school anthems.

- Mito City First Junior High School anthem, Ibaraki Prefecture (1952)

- Takaido Junior High School anthem, Suginami Ward, Tokyo (1957)

- Omura Junior High School anthem, Yaizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture (1957)

- Toyotama High School anthem, Tokyo (1951)

- Higashida Elementary School anthem, Suginami Ward, Tokyo (1951)

- Tajimi Kita High School anthem, Gifu Prefecture (1961)

- Omura Junior High School anthem, Yaizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture (year unknown)

- Fujimi Junior High School anthem, Niigata City, Niigata Prefecture (year unknown)

5. Family

Kyōsuke Kindaichi's immediate family faced considerable tragedy, with only one of his children surviving to old age.

- Wife:** Shizue (née Hayashi)

- Eldest daughter:** Ikuko (born 1911, died the following year from illness)

- Eldest son:** Haruhiko Kindaichi (renowned linguist, who lived to old age)

- Second daughter:** Yayoi (born 1915, died the same year)

- Third daughter:** Miho (born 1916, died the following year)

- Fourth daughter:** Wakaba (born 1921, committed suicide by drowning in the Tamagawa Aqueduct at age 28 due to chronic illness and loss of confidence in life)

Among Kyōsuke's children, only Haruhiko lived to full age.

His younger brother was Naoe Hirai, who served as the chairman of the HIzume Town Council. His uncle, Katsusada Kindaichi, was an industrialist, and Kunio Kindaichi, also an industrialist, was Katsusada's son-in-law (Kyōsuke's cousin's husband). Atsuko Kindaichi (born 1939), a renowned actress for Daiei Film, is Kunio's granddaughter.

6. Chronology

- 1882 (Meiji 15):** Born as the eldest son of Kindaichi Kumenosuke and Yasu.

- 1888 (Meiji 21):** Enters Morioka First Elementary School (now Niō Elementary School).

- 1892 (Meiji 25):** Enters Morioka Higher Elementary School (now Morioka Municipal Shimohashi Junior High School).

- 1896 (Meiji 29):** Enters Iwate Prefectural Morioka Junior High School (now Morioka First High School).

- 1901 (Meiji 34):** Enters Dai Ni Kōtō Gakkō (now Tohoku University).

- 1907 (Meiji 40):** Graduates from the Department of Linguistics, Tokyo Imperial University's Faculty of Letters. His graduation thesis was "Auxiliary Words in World Languages." In July, he travels alone to southern Sakhalin to research the Sakhalin Ainu language.

- 1908 (Meiji 41):** Appointed as a teacher at Kaijo Junior High School but loses his job in October. Ishikawa Takuboku moves to Tokyo. Kindaichi becomes a proofreader at Sanseido and a lecturer at Kokugakuin University.

- 1909 (Meiji 42):** Marries Shizue Hayashi on December 28.

- 1912 (Taishō 1):** Meets the elderly woman Koponanu of Shiwunkotsu at the Takushoku Exposition in Ueno, Tokyo. Questions her about yukar and the Ainu language. Ishikawa Takuboku dies.

- 1913 (Taishō 2):** From July to late August, at Koponanu's recommendation, he invites Wakarpa, a blind yukar storyteller from Shiwunkotsu, to Tokyo. He transcribes approximately 1,000 pages of the yukar "Kutneshirka" in Roman script. Wakarpa dies in his hometown at the end of the year.

- 1915 (Taishō 4):** In autumn, he visits Shiwunkotsu and records storytelling songs from elderly women.

- 1918 (Taishō 7):** Through an introduction from John Batchelor, he visits the home of Matsunari Chiri, meeting her mother, Monashinouku (described as the "last and greatest Yukarukuru"), and her then 16-year-old daughter, Yukie Chiri.

- 1922 (Taishō 11):** Becomes a professor at Kokugakuin University, later becoming an honorary professor.

- 1923 (Taishō 12):** Visits Kurokawa Tsunare of Nukibetsu, introduced by Wakarpa, and fully transcribes "Kutneshirka."

- 1925 (Taishō 14):** In April, appointed professor at the Faculty of Letters, Rikkyo University, upon recommendation from Yūzaburō Okakura.

- 1926 (Taishō 15):** Becomes a full-time lecturer at Taisho University (until 1940).

- 1928 (Shōwa 3):** Becomes an associate professor at Tokyo Imperial University.

- 1931 (Shōwa 6):** Publishes two volumes of Ainu Jojishi Yukarashū (A Study of Yukar: Ainu Epic Poetry).

- 1932 (Shōwa 7):** Receives the Imperial Prize for his 1931 work Ainu Jojishi Yukarashū.

- 1935 (Shōwa 10):** Obtains a Doctor of Letters degree. His thesis is "On the Grammar of Yukar, Especially its Verbs." Becomes president of the Tokyo University Shogi League (comprising Tokyo Imperial University, Tokyo University of Commerce, Waseda University, and Rikkyo University).

- 1940 (Shōwa 15):** Becomes a member of the NHK Broadcasting Language Committee (until 1962).

- 1941 (Shōwa 16):** Becomes a professor at Tokyo Imperial University (until 1943).

- 1942 (Shōwa 17):** Awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th Class.

- 1943 (Shōwa 18):** Retires from Tokyo Imperial University. Sanseido publishes Meikai Kokugo Jiten.

- 1948 (Shōwa 23):** Becomes a member of the Japan Academy.

- 1952 (Shōwa 27):** Becomes a member of the National Language Council (until 1958).

- 1954 (Shōwa 29):** Receives the Order of Culture.

- 1959 (Shōwa 34):** Awarded the title of the first Honorary Citizen of Morioka City. As of 2007, he remains the only honorary citizen of Morioka City.

- 1967 (Shōwa 42):** Becomes the second president of the Linguistic Society of Japan (until 1970).

- 1971 (Shōwa 46):** Dies at the age of 89. His posthumous Buddhist name is "Jutokuin Den Tetsu Gen Kamyo Daikoji." Posthumously conferred Junior Third Rank and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1st Class (an elevation from his previous rank of Junior Fourth Rank and Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th Class).

7. Assessment and Legacy

Kyōsuke Kindaichi's legacy is marked by his profound academic contributions, particularly in Ainu studies, alongside controversies concerning his methodologies and views on assimilation. His influence also extends beyond academia into popular culture.

7.1. Positive Assessment

Kyōsuke Kindaichi is widely regarded as the authentic founder of Ainu language research in Japan. He dedicated his entire life to the study of the Ainu language, enduring personal poverty. His grandson, the linguist Hideho Kindaichi, believes that without his grandfather's efforts, the Ainu language might not have survived. His extensive fieldwork and transcription of yukar, particularly the epic "Kutneshirka," are considered invaluable for the preservation of Ainu oral traditions. The publication of Yūkara no Kenkyū: Ainu Jojishi in 1931 was a monumental academic achievement, earning him the prestigious Imperial Prize. Furthermore, he played a crucial role in Japanese lexicography, contributing significantly to the compilation and supervision of major dictionaries like Meikai Kokugo Jiten, which became a bestseller and standard reference. His efforts to establish Standard Japanese, particularly through his role in the National Language Council, also contributed to the linguistic landscape of Japan. His dedication to scholarship was recognized with the highest honors, including the Order of Culture in 1954.

7.2. Criticism and Controversies

Despite his significant contributions, Kindaichi's work and perspectives, especially concerning the Ainu, have attracted criticism. His methods of collecting Ainu oral traditions, such as the forceful transcription from Kurokawa Tsunare, were later criticized as insensitive and exploitative. More fundamentally, his views on Ainu assimilation, particularly his belief that Ainu should abandon their language and assimilate into Japanese, have drawn strong condemnation. While he genuinely admired Ainu culture and recognized their "greatness," his writings reveal an underlying sentiment of cultural hierarchy, where he expressed personal loneliness and a sense of "regression" when studying "barbaric" or "low-level" cultures compared to Western philosophy. Post-World War II, he was specifically criticized for his implicit or explicit cooperation with the Japanese government's assimilation policies towards the Ainu. His complex relationship with his disciple Mashio Chiri, who later became a prominent Ainu linguist and criticized Kindaichi's research, further highlights the nuanced and sometimes problematic aspects of Kindaichi's approach. The controversy surrounding his efforts to suppress certain parts of Ishikawa Takuboku's Romaji Nikki further demonstrates a willingness to manipulate historical records to protect his family's reputation, casting a shadow on his academic objectivity in some matters.

7.3. Influence on Popular Culture

Kyōsuke Kindaichi's name holds a unique place in Japanese popular culture, notably inspiring the creation of the famous fictional detective Kōsuke Kindaichi, featured in the mystery novels of Seishi Yokomizo. When Yokomizo was writing The Honjin Murders, he initially considered "Kikuta Ichimaru" for his new detective, drawing inspiration from playwright Kazuo Kikuta. However, he later changed the name to "Kindaichi" after encountering "Kindaichi Yasuzō," a neighbor in Kichijoji, Tokyo, where Yokomizo lived until his evacuation to Okayama. Upon learning that Kindaichi Yasuzō was Kyōsuke Kindaichi's younger brother (an electrical engineer), Yokomizo decided to borrow Kyōsuke's given name as well, changing "Yasuzō" to "Kōsuke." Kyōsuke's son, Haruhiko Kindaichi, expressed profound gratitude to Yokomizo for making the "Kindaichi" surname, which was previously rare and often misread as "Kaneda," widely known and easily recognized by the public. This newfound familiarity alleviated the frequent difficulties Haruhiko faced with his surname, especially during his military service.

8. Awards and Honours

Kyōsuke Kindaichi received numerous awards and honors throughout his distinguished career, recognizing his significant contributions to Japanese linguistics and ethnology.

- Order of Culture (1954)

- Honorary Citizen of Morioka City (1959)

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1st Class, Grand Cordon (1971, Posthumous award)

- Junior Third Rank (1971, Posthumous award)