1. Overview

Kurt Georg Kiesinger, born on April 6, 1904, in Ebingen, German Empire, was a prominent German politician who served as the third Chancellor of West Germany from December 1, 1966, to October 21, 1969. His chancellorship marked a significant period in post-war German politics, as he led the first Grand Coalition government, bringing together the traditionally rival Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Prior to his time as Chancellor, Kiesinger served as the Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg from 1958 to 1966 and as President of the Federal Council from 1962 to 1963. He also held the position of Chairman of the Christian Democratic Union from 1967 to 1971.

Despite his distinguished political career and reputation as a brilliant orator, earning him the nickname "Chief Silver Tongue," Kiesinger's legacy remains deeply controversial due to his past affiliation with the Nazi Party. He joined the party in 1933 and worked in the Foreign Office's broadcasting department during World War II. This aspect of his biography sparked considerable public debate and protest, particularly from the West German student movement and anti-Nazi activists like Beate Klarsfeld, who publicly confronted him. His chancellorship, therefore, became a symbol of the challenges Germany faced in confronting its Nazi past and solidifying its democratic identity in the post-war era. The controversies surrounding his wartime activities amplified societal demands for accountability and historical truth, shaping the discourse on Germany's historical reckoning and the consolidation of its democratic institutions.

2. Early life and background

Kurt Georg Kiesinger's early life was shaped by his family background and his academic pursuits, which laid the foundation for his later political career.

2.1. Birth and family

Kurt Georg Kiesinger was born on April 6, 1904, in Ebingen, which was then part of the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire (now Albstadt, Baden-Württemberg). His father was a commercial clerk involved in the local textile industry and was a Protestant. His mother, Dominika Kiesinger (née Grimm), was Catholic and died six months after his birth. Kiesinger was baptized Catholic due to his mother's faith. His maternal grandmother played a significant role in his upbringing, encouraging him, while his father was largely indifferent to his advancement. A year after his mother's death, his father remarried Karoline Victoria Pfaff, who was also Catholic. They had seven children, including Kiesinger's half-sister Maria, who died a year after her birth. Influenced by both Protestant and Catholic denominations, Kiesinger later described himself as a "Protestant Catholic." He grew up in a politically liberal and democratically-minded environment, and in his youth, he was deeply interested in poetry, aspiring to become a poet.

2.2. Education and early career

Kiesinger began his higher education in 1925, initially studying history and philosophy at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen. In 1926, he transferred to Berlin University to study law and administration, graduating in 1931. He passed his first state legal examination in 1930 and his second in 1933. After obtaining his doctorate, Kiesinger remained in Berlin, where he began his career as a lawyer in 1935, also serving as a university law lecturer. He practiced law at Berlin's Kammergericht court until 1940. In 1932, Kiesinger married Marie-Luise Schneider, and they had two children.

3. Nazi Party membership and wartime activities

Kiesinger's involvement and activities during the Nazi era became a significant point of contention throughout his political career.

3.1. Joining the Nazi Party

Kurt Georg Kiesinger joined the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party, in February 1933, just weeks after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor. His party membership number was 2,633,930. According to Kiesinger himself, his motivation for joining the party as a Catholic was to connect with moderate Christian factions within the Nazi Party and to counteract its radical tendencies. Despite his membership, he claimed to have remained a largely inactive member.

3.2. Activities in the Foreign Office

In 1940, to avoid conscription into the military, Kiesinger secured a position in the Foreign Office's broadcasting department. He quickly rose through the ranks, becoming the deputy head of the department and the liaison to the Propaganda Ministry from 1943 to 1945. In this role, he worked under Joachim von Ribbentrop, who would later be condemned to death at the Nuremberg Trials, and had professional dealings with Joseph Goebbels, the head of the Propaganda Ministry.

During his tenure in the Foreign Office, Kiesinger's activities drew both criticism and defense. In 1944, two colleagues reportedly accused him of spreading defeatism and obstructing anti-Jewish activities within his department, according to a memorandum from November 7, 1944, later uncovered by Der Spiegel. However, other documents, including a Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) protocol, indicated that he had hindered anti-Jewish actions in his department, which later contributed to his release during denazification.

3.3. Post-war internment

Following the end of World War II, Kiesinger was detained by Allied forces, specifically the Americans, as a political prisoner in April 1945. He spent 18 months in the Ludwigsburg camp due to his connections with Ribbentrop, before being released in 1946. His release was based on a denazification court ruling that classified him as a passive sympathizer of the Nazi Party, effectively exonerating him. He then taught law at Würzburg University.

3.4. Criticisms regarding Nazi past

Kiesinger's Nazi past became a persistent source of controversy throughout his political career, particularly after he became Chancellor. Critics, including the Franco-German journalist and Nazi-hunter Beate Klarsfeld, asserted that Kiesinger had close ties to Ribbentrop and Goebbels. Klarsfeld specifically accused him of being primarily responsible for the content of German international broadcasts, which included anti-Semitic and war propaganda. She also claimed he collaborated closely with SS functionaries such as Gerhard Rühle and Franz Six, the latter of whom was responsible for mass murders in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe and was tried as a war criminal in the Einsatzgruppen Trial at Nuremberg. Klarsfeld alleged that Kiesinger continued to produce anti-Semitic propaganda even after becoming aware of the Holocaust. These allegations were partly based on documents published by Albert Norden of East Germany's ruling SED concerning war and Nazi criminals.

The controversy surrounding his past intensified during his chancellorship, especially with the rise of the West German student movement. Prominent writers like Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass were vocal critics; Grass notably wrote an open letter in 1966 urging Kiesinger not to accept the chancellorship. The historian Tony Judt observed that Kiesinger's chancellorship, much like Heinrich Lübke's presidency, highlighted a "glaring contradiction in the Bonn Republic's self-image" given their previous Nazi allegiances. This ongoing public debate underscored the inadequacy of Germany's process of coming to terms with its past and amplified demands for accountability and historical truth, significantly impacting public perception and the broader societal discourse on democratic consolidation.

4. Early political career

After World War II, Kurt Georg Kiesinger re-entered the political landscape, steadily rising within the newly formed West Germany.

4.1. Entry into the CDU

In 1946, Kiesinger joined the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), a newly established conservative party in post-war Germany. Concurrently, he provided private tutoring to law students and resumed his legal practice in 1948. In 1947, he also became the unpaid secretary-general of the CDU in Württemberg-Hohenzollern, demonstrating his early commitment to the party's organizational structure. In 1951, he became a member of the CDU executive board.

4.2. Bundestag activities

Kiesinger was first elected to the Bundestag, the West German parliament, in the 1949 West German federal election. He served as a member of the Bundestag from 1949 to 1958 and again from 1969 to 1980. In his initial term, he represented the Ravensburg constituency, where he achieved remarkable electoral results, securing over 70 percent of the vote. From 1969, he represented the Waldshut constituency. For the 1976 West German federal election, Kiesinger opted not to run in a direct constituency but entered parliament via the Baden-Württemberg state list of the CDU.

During his time in the Bundestag, Kiesinger gained a reputation for his exceptional rhetorical brilliance and his profound knowledge of foreign affairs. From 1949 to 1957, he chaired the mediation committee of the Bundestag and the Bundesrat. On October 19, 1950, he unexpectedly received 55 votes for President of the Bundestag, despite not being formally proposed, against his party colleague Hermann Ehlers (who received 201 votes). From December 17, 1954, to January 29, 1959, he served as chairman of the Bundestag Committee on Foreign Affairs, a committee he had been a member of since 1949.

Despite the recognition he garnered within the Christian Democrat parliamentary faction, Kiesinger was repeatedly overlooked for cabinet positions during various reshuffles. This perceived lack of advancement at the federal level ultimately prompted his decision to transition from federal to state politics. From 1955 to 1959, he also served as Vice-President of the Council of Europe, and from 1956 to 1958, he was a member of the European Parliament.

5. Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg

Kiesinger's leadership at the state level in post-war Germany was marked by significant achievements and a pragmatic approach to coalition building.

5.1. Tenure and key achievements

Kurt Georg Kiesinger assumed the office of Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg on December 17, 1958, a position he held until December 1, 1966. During this period, he was also a member of the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg, the state parliament. From November 1, 1962, to October 31, 1963, Kiesinger served as the President of the Bundesrat, a rotating position among the heads of Germany's federal states.

During his tenure as Minister-President, Kiesinger focused on stabilizing the newly formed state of Baden-Württemberg, which had been established in 1952. His notable accomplishments include the founding of two new universities: the University of Konstanz (in 1966) and the University of Ulm (in 1967), which significantly expanded educational opportunities in the region. He also achieved full employment within the state, improved living standards, and expanded healthcare facilities. Furthermore, he addressed environmental concerns, notably working on the water quality issues of Lake Constance.

5.2. Coalition governments

In the early years of the Federal Republic of Germany, it was not uncommon for states to form broad coalitions. Kiesinger initially led a coalition government in Baden-Württemberg comprising the CDU, the SPD, the FDP/DVP, and the BHE until 1960. Following the dissolution of the BHE on April 15, 1961, he then led a coalition of the CDU and the FDP until 1966.

6. Chancellorship (1966-1969)

Kurt Georg Kiesinger's term as Chancellor of West Germany was a pivotal period marked by significant political shifts, domestic reforms, and ongoing controversies.

6.1. Formation of the Grand Coalition

In 1966, the existing coalition government between the CDU/CSU and the FDP in the Bundestag collapsed, creating a political crisis. Kiesinger emerged as a leading candidate to replace Ludwig Erhard as Federal Chancellor. After winning an internal party ballot against rivals like Rainer Barzel and Gerhard Schröder, Kiesinger successfully negotiated with the SPD to form a new grand coalition. This alliance, which saw SPD leader Willy Brandt serve as Vice-Chancellor and Foreign Minister, was a landmark event in German post-war politics, as it brought the SPD into government for the first time since 1930. Despite some defections from the SPD during the vote, Kiesinger secured the support of over two-thirds of all Bundestag seats, marking the highest approval rate for a Chancellor nomination in post-war Germany.

6.2. Domestic policies

During Kiesinger's chancellorship, his government implemented a series of progressive domestic reforms aimed at improving social welfare, education, and labor conditions. These policies were enacted against a backdrop of economic stagnation and rising unemployment, with the Gross National Product (GNP) declining by 0.3% in 1967 compared to the previous year, and unemployment exceeding 500,000 by late 1966, surging to 670,000 by February 1967. The national budget was also in deficit, and the rise of the far-right National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) in state elections indicated growing social unrest.

To address these economic challenges, Kiesinger's government, particularly under Economics Minister Karl Schiller, enacted the Economic Stabilization and Growth Law in June 1967, which aimed to allow federal government intervention during economic downturns or overheating. This led to increased public investment and a subsequent economic recovery.

Key social reforms included:

- Pension Coverage:** In 1967, pension coverage was expanded by abolishing the income ceiling for compulsory membership, ensuring broader access to retirement benefits.

- Education:** Student grants were introduced, accompanied by a comprehensive university building program. A constitutional reform in 1969 granted the federal government the authority to collaborate with the Länder (states) on educational planning through joint commissions, fostering a more coordinated approach to education.

- Labor and Social Welfare:** Vocational training legislation was introduced, and unemployment insurance was reorganized to promote retraining schemes, counseling services, and job creation initiatives. The Lohnfortzahlunggesetz of 1969 mandated employers to pay full wages for the first six weeks of an employee's sickness. In August 1969, the Landabgaberente, a higher special pension, was introduced for farmers willing to relinquish unprofitable farms based on specific criteria.

- Judicial Reform:** Kiesinger's government also undertook judicial reforms, including establishing gender equality in divorce rights, granting illegitimate children legal rights equivalent to legitimate children, and decriminalizing homosexuality.

6.3. Foreign policy

Kiesinger's government pursued a foreign policy aimed at reducing tensions with Eastern Bloc nations, a precursor to the later Ostpolitik under Willy Brandt. Diplomatic relations were established with Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. However, Kiesinger generally opposed any major conciliatory moves, and his approach to Eastern European diplomacy became more cautious following the Prague Spring in 1968.

6.4. Controversies during chancellorship

Kiesinger's chancellorship was frequently overshadowed by intense public debate concerning his Nazi past, which was amplified by the burgeoning student movement. The historian Tony Judt noted that Kiesinger's position, like that of President Heinrich Lübke, exposed a "glaring contradiction in the Bonn Republic's self-image" given their previous Nazi allegiances.

A particularly infamous incident occurred on November 7, 1968, during a Christian Democrat convention in Berlin. Beate Klarsfeld, a prominent Nazi-hunter who campaigned with her husband Serge Klarsfeld against Nazi criminals, publicly slapped Kiesinger across the face while calling him a Nazi. She uttered the accusation in French, then, as she was being dragged out by two ushers, repeated it in German: "Kiesinger! Nazi! Abtreten!" (Kiesinger! Nazi! Step down!). Kiesinger, holding his left cheek, did not react or comment on the incident until his death, though he consistently denied that his 1933 entry into the Nazi Party was opportunistic. He did, however, admit that he joined the German Foreign Ministry in 1940 to avoid conscription into the Wehrmacht. Klarsfeld was initially sentenced to one year in prison without parole, which was later reduced to a four-month suspended sentence.

Other prominent critics included the writers Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass. Grass had written an open letter in 1966 urging Kiesinger not to accept the chancellorship. The philosopher Karl Jaspers even changed his nationality to Swiss in protest. The student movement, which gained significant momentum during this period, frequently protested against Kiesinger, viewing him as a symbol of Germany's failure to adequately confront its historical past. In May 1968, his government passed the Emergency Laws, which further fueled student protests.

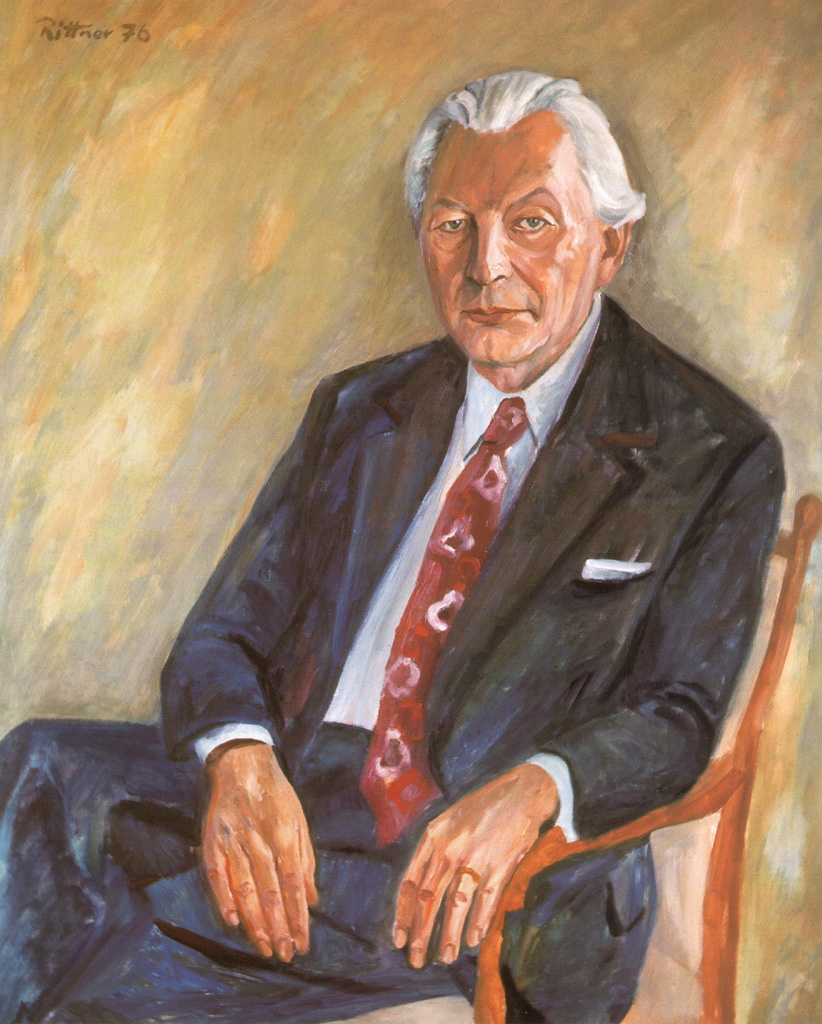

Kanzlergalerie Berlin

6.5. End of chancellorship

Following the 1969 West German federal election, the SPD, which had seen significant gains, chose to form a new coalition government with the FDP. This decision ended the uninterrupted post-war rule of CDU chancellors. Kiesinger was succeeded as Chancellor by his former Vice-Chancellor, Willy Brandt, marking a significant shift in West German political leadership. Kiesinger's chancellorship, lasting nearly three years, remains the shortest of any CDU Chancellor to date.

7. Later years and post-chancellorship

After concluding his term as Chancellor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger remained an influential figure in German politics and dedicated time to documenting his experiences.

7.1. Opposition leadership

Following the 1969 election, Kiesinger continued to lead the CDU/CSU in opposition until July 1971, when he was succeeded as Leader of the Christian Democratic Union by Rainer Barzel. He remained a member of the Bundestag until 1980, serving eight terms in total. In 1972, Kiesinger delivered the main speech justifying the constructive vote of no confidence initiated by the CDU/CSU parliamentary group against Chancellor Willy Brandt. However, this attempt to elect then-CDU leader Rainer Barzel as Chancellor was unsuccessful, reportedly due to bribery of CDU/CSU members Julius Steiner and possibly Leo Wagner by Stasi, the GDR's state security service.

7.2. Memoir writing

In 1980, Kiesinger retired from his political career and began working on his memoirs. Of his planned multi-volume autobiography, only the first part, titled Dunkle und helle Jahre: Erinnerungen 1904-1958 (Dark and Bright Years: Memoirs 1904-1958), was completed. This volume covered his life up to 1958 and was published posthumously in 1989.

8. Death and evaluation

Kurt Georg Kiesinger's passing and the subsequent historical assessment of his life reflect the enduring complexities of his legacy, particularly concerning his Nazi past and his role in Germany's post-war development.

8.1. Death and funeral

Kurt Georg Kiesinger died in Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, West Germany, on March 9, 1988, just 28 days before his 84th birthday. His funeral procession, which followed a requiem mass at St. Eberhard Church in Stuttgart, was notably accompanied by protesters, primarily students, who sought to ensure that his former membership in the Nazi Party was remembered and acknowledged.

8.2. Historical assessment and legacy

Kiesinger's historical assessment remains largely defined by the ongoing debate about his Nazi past. While recognized for his eloquence and mediation skills, which earned him the nickname "Chief Silver Tongue" (Häuptling SilberzungeGerman), his political career, particularly his chancellorship, is often viewed through the lens of Germany's struggle to confront its history. His leadership of the Grand Coalition was significant for bringing the SPD into government for the first time in decades, marking a shift towards broader political consensus in West Germany.

His chancellorship saw notable achievements in domestic policy, including social welfare reforms, educational expansion, and judicial modernizations that promoted social equity, such as equal divorce rights and legal recognition for illegitimate children. Economically, his government successfully navigated a period of recession, implementing policies that led to recovery. In foreign policy, he initiated efforts to improve relations with Eastern Bloc countries, laying groundwork for Ostpolitik.

However, the persistent public scrutiny and protests regarding his Nazi Party membership, especially the incident with Beate Klarsfeld, highlighted the deep societal demand for accountability and historical truth. His presence in high office symbolized, for many, the perceived inadequacy of Germany's process of "coming to terms with the past" (VergangenheitsbewältigungGerman). This controversy underscores the critical impact of his actions on democratic development and social progress, as it forced a national conversation about the moral integrity of its leadership and the need for a thorough historical reckoning.

8.3. Influence

Kiesinger's broader impact on German politics and society is multifaceted. He demonstrated the viability of a grand coalition, which contributed to political stability during a period of economic uncertainty and social upheaval. His ability to unite disparate political forces under his leadership, despite his controversial past, showcased his considerable skills as a mediator and orator.

The continuous public discourse surrounding his Nazi affiliation, however, profoundly influenced Germany's approach to historical memory and reconciliation. The protests against him, particularly from the student movement, became a catalyst for a more critical engagement with the nation's wartime history and a demand for greater transparency and accountability from its leaders. His legacy thus serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring challenges of confronting a difficult past and the continuous process of democratic consolidation in Germany.

9. Personal life

Outside of his public political career, Kurt Georg Kiesinger maintained a private life centered around his family.

9.1. Marriage and family

Kurt Georg Kiesinger was married to Marie-Luise Schneider on December 24, 1932. Together, they had two children.

10. Books

Kurt Georg Kiesinger was an author of poetry and various books, including autobiographical writings and collections of speeches. His notable published works include:

- Schwäbische Kindheit. (Swabian childhood.), Wunderlich Verlag, Tübingen 1964.

- Ideen vom Ganzen. Reden und Betrachtungen. (Ideas from the whole. Speeches and reflections.), Wunderlich Verlag, Tübingen 1964.

- Stationen 1949-1969. (Stations 1949-1969.), Wunderlich Verlag, Tübingen 1969.

- Die Stellung des Parlamentariers in unserer Zeit. (The position of the parliamentarian in our time.), Stuttgart 1981.

- Dunkle und helle Jahre: Erinnerungen 1904-1958. (Dark and Bright Years: Memoirs 1904-1958.), Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1989.