1. Overview

Kunisada Chūji (国定 忠治Kunisada ChūjiJapanese, also spelled 忠次ChūjiJapanese, 1810 - January 22, 1851), born 長岡忠次郎Nagaoka ChūjirōJapanese, was a prominent 侠客kyōkakuJapanese and 博徒bakutoJapanese (gambler) active in the late Edo period of Japan. His name "Kunisada" derives from his birthplace, Kunisada Village in Sai District, Kōzuke Province (modern-day Gunma Prefecture). Chūji's activities, primarily spanning Joshu and Shinshu, led to his de facto control over a territory he called "盗区TōkuJapanese." He is widely celebrated as a chivalrous figure, often romanticized as a "Robin Hood"-like bandit who aided the common people, particularly during the devastating Tenpō Famine.

His legend has been extensively depicted in Japanese popular culture, becoming a staple subject in 講談kōdanJapanese (storytelling), 浪曲rōkyokuJapanese (narrative singing), films, and stage plays, including the renowned 新国劇Shin KokugekiJapanese (New National Theater) productions. His most famous line, "Akagi no Yama mo Konya o Kagiri," became a widely recognized theatrical phrase, cementing his image as a tragic yet principled hero. While historical debates exist regarding the full extent of his benevolent actions, contemporary accounts suggest his significant involvement in poverty relief, contributing to his enduring image as a defender of the people. Posthumously, his grave sites are maintained in Isesaki, and his legacy continues to be acknowledged, even appearing on a 1999 Japanese stamp, symbolizing his deep roots in popular Japanese consciousness.

2. Life

Kunisada Chūji's life was marked by a dramatic progression from a privileged but troubled youth to a notorious *bakuto*, culminating in his public execution and subsequent posthumous reverence.

2.1. Early Life and Background

Kunisada Chūji was born in 1810 in Kunisada Village, Sai District, Kōzuke Province, which is now part of Kunisada-chō, Isesaki, Gunma, Gunma Prefecture. His family, the Nagaoka, were affluent farmers (豪農gōnōJapanese) residing at the southern foot of Mount Akagi. Their livelihood revolved around cultivating rice and wheat, supplemented by sericulture during the agricultural off-season. According to a tombstone at Yōju-ji, the Nagaoka family's ancestral temple, his father, Yogozaemon, a farmer from Kunisada Village, passed away on May 20, 1819. His mother died later, on May 14, 1845.

With his father's early death, the young Chūji became a 無宿musukuJapanese, a rootless person, in his youth, as the family headship was passed to his younger brother, Tomozō (who lived until 1878). Despite Chūji's unsettled life, Tomozō, who expanded the family business into silk and thread trading, provided shelter and support for his elder brother. Both Chūji and Tomozō are believed to have received their education at the 寺子屋terakoyaJapanese (temple school) located within Yōju-ji, under the guidance of the resident priest, Teizen. A financial promissory note from Tomozō to Chūji, preserved at Yōju-ji, further indicates their close relationship and Tomozō's ongoing support.

2.2. Entry into the Bakuto World

Chūji's entry into the world of *bakuto* began when he inherited the gambling territory of Ōmaeda Eigorō from Ōmaeda Village in Seta District, Kōzuke Province (modern-day Maebashi, Gunma). He established himself as the boss of Dodomura, and his base of operations was the way-station of Sakaichō on the Nikkō Reiheishi Kaidō (highway). This brought him into direct conflict with Shimamura Isaburō, a rival *bakuto* boss based in Sakai-machi, who was an adversary of Eigorō.

Chūji raided Isaburō's territory and was subsequently captured. However, Isaburō, for reasons unknown, spared his life. Despite this act of clemency, Chūji harbored deep resentment towards Isaburō. The simmering animosity escalated in 1834 when Chūji's subordinate, Miki Bunzō, engaged in a skirmish with Isaburō's faction. Seizing this opportunity, Chūji assassinated Isaburō and seized control of his territory. Following this act, he temporarily retreated to Shinshu Province, an area outside the direct jurisdiction of the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku (Kantō Regulators). Upon his return to Joshu, he solidified his power and formed his own *ikka* (gang or family). Historical records such as "Akagiroku" by Hakura Kantō portray Chūji's followers, including Nikkō Enzō, as numerous and loyal, likening them to the heroes of the Chinese classic, *Water Margin* (*Suikoden*). *Akagiroku* specifically notes, "There were many righteous brothers and sons," implying a large and devoted following. This portrayal was also reflected in Meiji-era historical accounts, such as *Kaei Suikoden Kunisada Chūji Jikki*.

2.3. Major Activities and Escapes

After establishing his *ikka*, Kunisada Chūji's influence grew, leading to a series of escalating conflicts and periods of evasion from the authorities. He became embroiled in a bitter rivalry with the Tamamura brothers, Kyozō and Shuma, who operated from Tamamura-juku along the Nikkō Reiheishi Kaidō. The conflict intensified in 1835 when the Tamamura brothers raided the gambling den of Min'gorō of San'ōdō Village (山王民五郎San'ō Min'gorōJapanese). Chūji responded by dispatching two of his subordinates to attack and drive out the Tamamura brothers.

In 1838, a significant blow befell Chūji's group when a gambling den in Serada was raided by the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku. Miki Bunzō, one of Chūji's key subordinates, was captured. Chūji attempted to rescue him but failed, and the intensified pursuit by the regulators forced him to flee. His group suffered further losses with the execution of Bunzō and other loyal subordinates, Kanzaki Tomogorō and Hachisun Saizuke. In response to widespread corruption within the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku, the Shogunate reformed and re-staffed the organization in 1839, leading to an even more rigorous crackdown on *bakuto*. Among the newly appointed officials was Nakayama Seiichirō, a former aide to Hakura Kantō.

The conflicts continued in Chūji's absence. In 1841, while Chūji was in Aizu, Tamamura Shuma killed San'ō Min'gorō, sparking renewed hostilities. Chūji returned the following New Year and retaliated by killing Shuma. Records from Hakura Kantō's "Akagiroku" notably describe Chūji carrying "Western-style short guns" during this period. *Akagiroku* specifically mentions that Chūji selected eighteen of his "righteous sons," each carrying "Western-style short guns," when going on missions. While it's unlikely he possessed modern firearms, it is believed he may have used matchlock pistols, such as the "Chūji's beloved pistol" preserved at the Ōshima Giemon's house in Isesaki. *Akagiroku* also states that in 1836, when seeking revenge for the murder of his brother-in-law Kayaba Chōhei, Chūji and twenty followers carried "fire spears and polearms," though it is improbable these were literally Chinese weapons. Later, in August 1842, Chūji committed another grave offense by killing Mimuro Kansuke and Tarokichi, a father-son duo who served as guides and detectives for the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku. Mimuro Kansuke (also known as Nakajima Kansuke or Kosai Kansuke) hailed from Mimuro, Obokata Village, Joshu, where his Nakajima family served as village headmen. Asajirō, one of Chūji's subordinates, was Kansuke's nephew. After losing a lawsuit against Kenkai, the chief priest of Chōan-ji temple in Nishi-Obokata Village, and the lord Hisanaga, Kansuke moved to the neighboring Hachisun Village in 1841 and began working as a guide for the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku. This act led to an immediate and full-scale manhunt by officials like Nakayama Seiichirō, with Chūji and his entire *ikka* being placed on an urgent wanted list.

The Shogunate further tightened control over *bakuto* and *musuku* in 1842 in preparation for Shogun Tokugawa Ieyoshi's rare visit to Nikkō in April 1843. Under immense pressure, Chūji was forced to break through the Ōdo barrier on the Shinshū Kaidō (now National Route 406) in Ōdo, a village in Agatsuma District (modern-day Higashiagatsuma, Gunma). He managed to escape to Aizu, though he lost valuable subordinates, including Nikkō Enzō and Asajirō, during his flight.

2.4. Tenpō Famine Relief Controversy

One of the most enduring aspects of Kunisada Chūji's legend is his supposed altruism during the devastating Tenpō Famine (1833-1839). Popular accounts claim that Chūji sold his family's assets to purchase provisions, which he then distributed among the impoverished residents of Kunisada Village, thereby earning him the moniker of a "chivalrous bandit" or "Robin Hood" figure.

However, the historical authenticity and extent of these actions have been a subject of debate among historians. Eitarō Tamura, a local historian from Takasaki, argued against the veracity of these widely circulated stories. Despite such skepticism, a significant piece of evidence supports Chūji's involvement in famine relief. Hakura Kantō, a Kantō *daikan* (magistrate) and contemporary of Chūji, recorded in his diary, "Senzairoku," during his inspection tour in 1837: "There is a thief in the mountains named Chūji. He has dozens of followers. Since last winter, he has repeatedly helped the poor and orphans." This entry, along with similar mentions in "Akagiroku" (written after Chūji's death), suggests that regardless of the specific details or the romanticized nature of later narratives, Chūji did engage in activities perceived as aiding the impoverished. This historical context provides a basis for his enduring image as a figure who, despite his criminal activities, demonstrated compassion and support for the common people during a period of severe hardship.

2.5. Later Years and Capture

By 1846, Kunisada Chūji returned to Joshu Province, but his health had significantly deteriorated. He suffered from 中風chūfūJapanese (stroke), which severely impacted his physical capabilities. In 1848, acknowledging his declining health, Chūji formally transferred the leadership of his *ikka* to his trusted subordinate, Sakigawa Yasugorō.

Despite passing on his leadership, Chūji remained in Joshu, relying on the network within his "盗区tōkuJapanese" for shelter and protection. However, his period of relative safety came to an end on August 24, 1850 (September 29, 1850, by the Gregorian calendar), when he was finally captured by the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku at the residence of a village headman in Tabey Village. Simultaneously, many of his key subordinates were also apprehended in a coordinated operation. Following his capture, Chūji was transported to Edo, where he was interrogated at the official residence of Ikeda Yorikata, the Kanjo Bugyo (Finance Magistrate) and Dōchū Bugyo (Highway Magistrate). He was then incarcerated in the notorious Kodenma-chō Prison.

2.6. Execution and Posthumous Treatment

Kunisada Chūji faced numerous charges, including gambling, murder, and incitement to murder. However, the most severe crime for which he was condemned was breaking through the Ōdo barrier, a direct challenge to shogunate authority. Consequently, by order of Ikeda Yorikata, Chūji was transported back to Kōzuke Province and publicly executed by 磔haritsukeJapanese (crucifixion) at the Ōdo execution ground in Ōdo Village, Agatsuma District (now part of Higashiagatsuma, Gunma). He was 41 years old at the time of his death.

After his execution, Chūji's body, including his head, was displayed for three days as a deterrent before being discarded. However, his remains were secretly retrieved by unknown individuals. According to a document (一札issatsuJapanese) written by Hōin Teizen, the resident priest of Yōju-ji in Kunisada Village, he clandestinely obtained Chūji's head and performed a proper memorial service. When the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku intensified their search for the missing head, Teizen reportedly exhumed it and reburied it in a secret location to protect it. Teizen's document also records Chūji's posthumous Buddhist name (戒名kaimyōJapanese) as "Nagaokain Hōyo Karaku Koji."

In 1861, which marked the 13th anniversary of Chūji's death, Teizen passed away. In September of that year, a 地蔵JizōJapanese statue dedicated to Chūji was erected at the former Ōdo execution ground site. This memorial was organized by Tsuchiya Jūgorō of Ōdo Village and Kasumi Tōzaemon, from either Honjuku or Ōkashiwagi Village. Furthermore, at Zen'ō-ji in Kuruwa-machi, Isesaki City, Gunma Prefecture, a monument known as "Jinjin-bun" (情深墳Jinjin-bunJapanese, "Tomb of Deep Affection") was erected by Kikuchi Toku, one of Chūji's mistresses. This monument records his *kaimyō* as "Yūdō Karaku Koji," indicating a slightly different posthumous name. In 1882, Gonta, the heir of the Nagaoka family, erected a grave monument for Chūji and his wife, with the inscription penned by Arai Jakuri, a Confucian scholar from the former Isesaki Domain, further solidifying Chūji's place in local history.

3. Character and Anecdotes

Kunisada Chūji's persona, a blend of toughness, compassion, and wit, is vividly painted through historical descriptions and numerous popular anecdotes that have been passed down through generations.

3.1. Physical Appearance and Reputation

Historical records provide a detailed physical description of Kunisada Chūji. A wanted poster circulated by the Kantō Torishimari Deyaku to the village headman of Shimoniita described his appearance as: "Medium height, remarkably stout, with a round face, a straight nose, and fair skin. He had a large 大たぶさō-tabusaJapanese (topknot style) and thick eyebrows. Generally, he gave the impression of a sumo wrestler." This depiction suggests a robust and imposing figure, reflecting his reputation as a powerful and formidable *bakuto*.

Among the common people, Chūji's reputation was encapsulated in a chillingly poetic saying: "Kunisada Chūji is scarier than an ogre, smiling as he cuts down men." This phrase illustrates the popular perception of him as a ruthless and fearsome opponent in a fight, yet perhaps hinting at a charismatic or deceptive calm. This dual image of formidable strength and a hint of unexpected demeanor contributed to his legendary status.

3.2. Notable Anecdotes

Numerous anecdotes illustrate Kunisada Chūji's character, highlighting his courage, quick wit, and distinctive personality.

One famous story involves a challenge to the renowned sword master Chiba Shusaku, founder of the Hokushin Ittō-ryū school of swordsmanship. Confident in his own martial prowess, Chūji rode into Chiba's dojo, intending to challenge him to a real duel. However, upon observing Chūji's stance, Chiba Shusaku immediately perceived the inevitable outcome of such a confrontation and promptly left the scene, avoiding the challenge. Chūji, initially frustrated, was then persuaded by Chiba's disciples to leave. He later realized that Chiba had recognized his skill and, by walking away, had implicitly saved Chūji's life, an act of respect rather than cowardice.

Another tale recounts Chūji's journey west into 遠江国Tōtōmi ProvinceJapanese (Enshū). In Kakegawa, he deliberately chose to stay at an inn without seeking the patronage of the local *bakuto* boss, Tōyama no Ryūzō, who was known for his demanding nature. Ryūzō, enraged by this perceived slight to his authority, pursued Chūji with the intention of taking his life. When they met, Chūji calmly confirmed his adversary's identity as Ryūzō. Without a hint of fear, he uttered the now-famous line, "Chūji is on a pilgrimage to Ise. Will you join?" and then walked away. Ryūzō, left utterly dumbfounded, would recount this incident for years, praising Chūji's extraordinary courage and remarkable presence, affirming that Chūji was indeed "a great man" as he had heard. This anecdote, recorded in Muramoto Kiyozo's "Enshū Kyōkakuden," highlights Chūji's legendary bravado.

A third anecdote, noted in Tomoya Masuda's "Shimizu Jirochō and His Surroundings" (1974), reveals a more earthy side of Chūji. While he was hiding in Shinshu, he sought refuge at the home of a local *oyabun* (boss). The *oyabun*'s wife grumbled about the increasing number of travelers straining their provisions. Chūji, overhearing her complaints, declared, "I've eaten borrowed rice since I was fifteen. I don't know the price of rice. And I was born without knowing restraint." He then demanded an entire salted salmon be roasted and proceeded to consume over ten large black bowls of rice, deliberately causing discomfort and embarrassment to the penny-pinching wife. This story showcases his disdain for miserliness and his unyielding, somewhat boorish, independence.

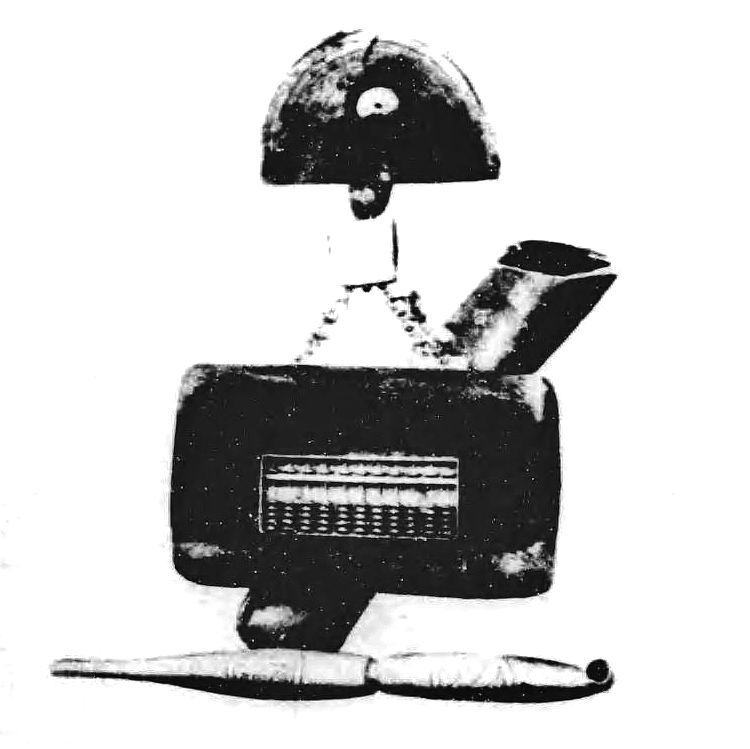

Kunisada Chūji was also known to be an avid smoker. He notably favored a leather cigarette case that incorporated a small abacus, a tool often used by *bakuto* for quick calculations related to gambling. This unique accessory became part of his distinct image, symbolizing the practical and calculating nature sometimes necessary in the world he inhabited.

4. Cultural Depictions

Kunisada Chūji's dramatic life and romanticized image have inspired a vast array of cultural works, cementing his place as an enduring legend in Japanese art and media.

4.1. Stage Plays

Kunisada Chūji's story became a staple in traditional and popular Japanese theater, particularly in the 新国劇Shin KokugekiJapanese (New National Theater) and 大衆演劇Taishū EngekiJapanese (popular theater) genres. The first stage adaptation was 『國定忠治』Kunisada ChūjiJapanese, which premiered in 1919 (Taisho 8) at the Bentenza theater in Osaka, with the script penned by Gyōtomo Rifū.

The original cast for this inaugural production featured prominent actors of the era:

- Kunisada Chūji - Sawada Shōjirō

- Itawari no Asatarō - Tanaka Keiji

- Shimizu Gantetsu - Kanai Kinnosuke

- Takayama Teihachi - Ogawa Takashi

- Nikkō Enzō - Kurahashi Sentarō

- Kawadaya Sōbei - Nakata Shōzō

The current script for "Kunisada Chūji" is typically structured into five acts and seven scenes. However, it was rare for the play to be performed in its entirety; the darker, more tragic latter half was often omitted. Performances frequently focused on the key dramatic sections, such as "Akagi Tenjin-yama Fudō no Mori" (Mount Akagi, Fudō Forest) from the second act, extending to "Hangō no Matsunami-ki" (Pine Trees of Hangō) in the third act, or even just the "Akagi Tenjin-yama Fudō no Mori" scene. In 2007, a full-length performance, structured into four acts and seven scenes, was staged at the National Theatre with the participation of Shōji Ogata, a *Shin Kokugeki* alumnus. This performance highlighted the "Mount Akagi Tenjin-yama" scene as a climax, with the final fourth act deepening the drama through its tragic conclusion. This particular scene is famous for two iconic lines that have become synonymous with Kunisada Chūji and permeated Japanese popular culture, much like classic 歌舞伎KabukiJapanese *kimezerifu* (dramatic poses or lines). The first is his poignant farewell: "赤城の山も今夜を限り、生れ故郷の國定の村や、縄張りを捨て国を捨て、可愛い子分の手めえ達とも、別れ別れになる首途(かどで)だAkagi no Yama mo Konya o Kagiri, Umare Kokyō no Kunisada no Mura ya, Nawabari o Sute Kuni o Sute, Kawaii Kobun no Temē-tachi tomo, Wakare Wakare ni Naru Kadode daJapanese" (Tonight is the last night on Mount Akagi; I leave my birthplace, Kunisada village, abandoning my territory and my home, parting ways with my beloved subordinates). The second, uttered as he brandishes his sword, is: "加賀の国の住人小松五郎義兼が鍛えた業物、万年溜の雪水に浄めて、俺にゃあ、生涯手めえという強い味方があったのだKaga no Kuni no Jūnin Komatsu Gorō Yoshikane ga Kitaeta Wazamono, Mannen Tame no Yukimizu ni Kiyomete, Ore nyaa, Shōgai Temē to Iu Tsuyoi Mikata ga Atta no daJapanese" (This masterpiece forged by Komatsu Gorō Yoshikane of Kaga Province, purified by the eternal snowmelt, you have been my lifelong strong ally). These lines profoundly shaped the public's image of Kunisada Chūji.

In popular theater, a long play covering Kunisada Chūji's life up to his execution was performed by Saizō Akira (now Soganoya Akira) in May 2011. The narrative also finds its way into the special performances of 演歌enkaJapanese singers, with Saburō Kitajima notably incorporating Kunisada Chūji's story into his theatrical concerts.

4.2. Films

Kunisada Chūji's life and legend have been adapted into numerous films, spanning both the pre-war and post-war eras, each offering unique interpretations of the popular hero.

4.2.1. Pre-war Films

- 実説国定忠治 雁の群Jissetsu Kunisada Chūji Kari no MureJapanese (1923, Shochiku Kinema Kamata Studio), directed by Nomura Yoshitei, starring Yōtarō Katsumi.

- Chūji Tabi Nikki (1927, Nikkatsu Taishōgun Studio), directed by Daisuke Itō, starring Denjirō Ōkōchi.

- 国定忠治Kunisada ChūjiJapanese (1933, Chiezō Productions), directed by Hiroshi Inagaki, starring Chiezō Kataoka. This film was an adaptation of a newspaper novel by Kan Shimozawa. Both Noriko Awaya and Tadaharu Nakano (with lyrics by Shimozawa) released popular theme songs for the film.

- 浅太郎赤城の唄Asatarō Akagi no UtaJapanese (1934, Shochiku Kinema), directed by Kōsaku Akiyama, starring Kōkichi Takata. This marked Shochiku Kinema's first sound film. While the film was significant, the theme song, "Akagi no Komoriuta" (Akagi Lullaby) by Tarō Shōji, became a massive hit independently.

- 國定忠治 信州子守唄Kunisada Chūji Shinshū KomoriutaJapanese (1936, Makino Talkie Productions), directed by Masahiro Makino, starring Ryūnosuke Tsukigata.

- 忠治血笑記Chūji KesshōkiJapanese (1936, Makino Talkie Productions), co-directed by Tameyoshi Kubo and Masahiro Makino, starring Junnosuke Hayama.

- 忠治活殺剱Chūji Kassatsu KenJapanese (1936, Makino Talkie Productions), co-directed by Tameyoshi Kubo and Masahiro Makino, starring Eitarō Shimizu.

4.2.2. Post-war Films

- 国定忠治Kunisada ChūjiJapanese (1946, Daiei), directed by Teiji Matsuda, starring Tsumasaburō Bandō.

- 国定忠治Kunisada ChūjiJapanese (1954, Nikkatsu), directed by Eisuke Takizawa, starring Ryūtarō Tatsumi. Tatsumi's portrayal of Chūji was a signature role from his *Shin Kokugeki* repertoire.

- 赤城の血煙 国定忠治Akagi no Chikeburi Kunisada ChūjiJapanese (1957, Shochiku), based on the original work by Kan Shimozawa, directed by Harukazu Fukuda, starring Kōkichi Takata.

- 国定忠治Kunisada ChūjiJapanese (1958, Toei), based on the original work by Gyōtomo Rifū, directed by Teiji Matsuda, starring Chiezō Kataoka.

- 国定忠治Kunisada ChūjiJapanese (1960, Toho), directed by Senkichi Taniguchi, with a screenplay by Kaneto Shindō, starring Toshirō Mifune.

- 浪曲国定忠治 赤城の子守唄 血煙り信州路Rōkyoku Kunisada Chūji Akagi no Komoriuta Chikeburi ShinshūjiJapanese (1960, Daini Toei), directed by Taizō Fuyushima, starring Keinosuke Wakasugi.

4.3. Literature

Kunisada Chūji's life and the romanticized versions of his exploits have provided fertile ground for numerous literary works, ranging from long novels to short stories.

- Long Novels:**

- Short Novels:**

4.4. Music and Television Dramas

Kunisada Chūji's story has also been immortalized in various forms of Japanese music and adapted for television.

In music, his tale is notably featured in 八木節YagibushiJapanese, a traditional folk song style originating from the Gunma region. Beyond folk music, his legend has been central to several popular songs, most notably those by Tarō Shōji. His hits include "Akagi no Komoriuta" (Akagi Lullaby, 1934), "忠治子守唄Chūji KomoriutaJapanese" (Chūji Lullaby, 1938), "名月赤城山Meigetsu Akagi-yamaJapanese" (Moonlit Mount Akagi, 1939), and "さらば赤城よSaraba Akagi yoJapanese" (Farewell, Akagi, 1947). These songs further ingrained Chūji's image into the public consciousness.

On television, Kunisada Chūji's narrative has been the subject of several dramas:

- Zatoichi Monogatari - Episode 16, "赤城おろしAkagi OroshiJapanese" (Akagi Wind, 1975), based on Kan Shimozawa's original work, with the role of Chūji played by Ryūtarō Tatsumi.

- 天下堂々Tenka DōdōJapanese (Magnificent Under Heaven, 1973-1974), featuring Hatsuo Yamaya as Chūji.

- Chūji Tabi Nikki (Chūji's Travel Diary, 1992), starring Kin'ya Kitaōji as the protagonist.

5. Historical Assessment and Legacy

Kunisada Chūji's historical assessment remains complex, oscillating between factual accounts of a *bakuto* and the deeply ingrained popular image of a "chivalrous bandit." His legacy continues to resonate in contemporary Japan, influencing cultural perceptions and even inspiring acts of reconciliation.

5.1. "Chivalrous Bandit" Image and Historical Debate

The image of Kunisada Chūji as a "chivalrous bandit" or "Robin Hood" figure is deeply rooted in Japanese folklore and popular narratives. This romanticized portrayal often emphasizes his alleged acts of charity, particularly during the severe Tenpō Famine. Accounts suggest he sold his possessions to aid suffering villagers, a narrative that resonated deeply with a populace grappling with hardship and inequality under the feudal system.

However, historical scholarship presents a more nuanced view. While popular tales often paint him as a selfless hero, some historians, such as Eitarō Tamura, have expressed skepticism about the extent of his benevolent actions, suggesting that later legends may have embellished the truth. Nevertheless, contemporary historical documents, notably the diary "Senzairoku" by Hakura Kantō (a Kantō *daikan*), provide strong evidence supporting his charitable activities. Hakura Kantō's entry from 1837 mentions a "thief in the mountains named Chūji" who "repeatedly helped the poor and orphans." This contemporaneous account, though brief, lends credibility to the idea that Chūji was indeed perceived as someone who aided the impoverished.

The proliferation of his story in 講談kōdanJapanese, 浪曲rōkyokuJapanese, and especially the 新国劇Shin KokugekiJapanese significantly contributed to the solidification of his "chivalrous bandit" image. These popular theatrical and storytelling forms often highlighted his loyalty to his followers, his bravery against rivals, and his perceived justice against corrupt authority figures, transforming him from a mere criminal into a folk hero who acted on behalf of the common people. This public perception, regardless of absolute historical accuracy, reflects a societal longing for figures who defy oppressive systems to protect the vulnerable.

5.2. Modern Significance and Reconciliation

Kunisada Chūji's legacy remains relevant in modern Japan, reflecting a continued fascination with his story and the themes of justice and chivalry. His enduring presence in popular culture is evidenced by his depiction on a 1999 Japanese postage stamp, a clear acknowledgment of his iconic status within the national consciousness.

Beyond cultural commemoration, Chūji's legacy has even led to acts of historical reconciliation. On June 2, 2007, a groundbreaking 手打ち式teuchi-shikiJapanese (reconciliation ceremony) was held, mediating a peace between the descendants of Kunisada Chūji and those of his adversaries, Shimamura Isaburō and Mimuro Kansuke. This reconciliation, organized by the "Chūji Danbeikai," marked a symbolic end to a 170-year-old conflict. This event not only highlighted the deep historical roots of Chūji's story but also demonstrated a modern desire to bridge past animosities and foster unity among communities impacted by historical figures like him. The ceremony underscores the enduring power of his legend and its capacity to inspire dialogue and resolution even centuries later.

6. Related Sites and Memorials

Numerous historical sites and memorials across Japan, particularly in Gunma and Nagano Prefectures, serve as tangible links to the life and legend of Kunisada Chūji.

6.1. Gunma Prefecture

Gunma Prefecture, being Kunisada Chūji's birthplace and primary area of activity, hosts several significant sites related to his life and legend.

- Yōju-ji and Nagaoka Chūji no Haka (Isesaki City): This is the ancestral temple of the Nagaoka family, where Kunisada Chūji's primary grave is located. It is often surrounded by a fence, indicating its importance.

- Zen'ō-ji and Jinjin-bun (Isesaki City): At this temple, a monument known as "Jinjin-bun" (Tomb of Deep Affection) was erected by Kikuchi Toku, one of Chūji's mistresses.

- Shōnen-ji and Iegamo-zuka (Tamamura Town): This temple is home to the "Iegamo-zuka" (Duck Mound), a site associated with Chūji, though the specific anecdote is not widely known.

- Chūji Tomadoi no Matsu (Higashiagatsuma Town): Known as the "Pine of Chūji's Hesitation," this pine tree marks a spot where Chūji is said to have paused, perhaps contemplating his escape or next move.

- Chūji Jizō (Higashiagatsuma Town): A Jizō statue dedicated to Chūji, erected at the site of his execution, commemorates his life and eventual death.

- Ōdo Sekisho (Higashiagatsuma Town): The remains of the Ōdo Barrier, a crucial checkpoint that Chūji famously broke through during his escapes from authorities.

- Akagi Onsenkyō, Chūji Onsen (Maebashi City): A hot spring within the Akagi Hot Spring Village named after Chūji, linking him to the natural landscape of the region he frequented.

6.2. Nagano Prefecture

Nagano Prefecture, where Kunisada Chūji often sought refuge during his periods of escape, also preserves several sites connected to his legend.

- Jizō-dō at Jusenin (Kamimachi, Suzaka City): This temple hall is associated with Chūji's presence during his time in hiding.

- Kunisada Chūji no Hahi (Gondō-chō, Nagano City): A grave monument dedicated to Kunisada Chūji is located within the precincts of Akiba Jinja in Gondō-chō.

- Chūji no Kakureiwa (Shiga Kōgen Sumikawa Hotel): Known as "Chūji's Hidden Rock," this site near the Maeyama Lift Station in Shiga Kōgen is believed to have been one of his hiding places.

- Reconstructed Chūji Jizō (Nozawaonsen Village): A Jizō statue dedicated to Chūji has been reconstructed in this village, maintaining his connection to the area.

- Stone bridge near Hachikagō Suidori-iri (Matsuzaki, Nakano City): An ancient stone bridge near the Hachikagō Irrigation Inlet, which local legend states Kunisada Chūji crossed.

- Kusatsudō (Chūji) no Ishibashi (Stone Bridge on Kusatsu Road): A preservation society has worked to restore the old Kusatsu Road and erected a guide stone monument for this stone bridge, which is also linked to Chūji's travels.