1. Overview

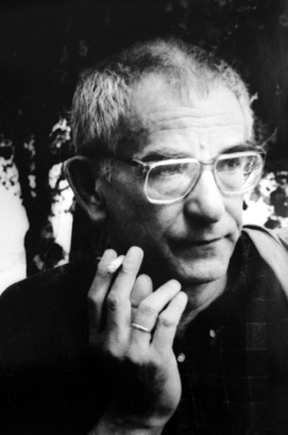

Krzysztof Kieślowski (Krzysztof KieślowskiKSHISH-tof kye-SHLOF-skiPolish, born on June 27, 1941) was a highly influential Polish film director and screenwriter whose works are celebrated for their profound humanistic approach and exploration of complex moral and existential dilemmas. Internationally, he is best known for his seminal television series Dekalog (1989), the critically acclaimed philosophical film The Double Life of Veronique (1991), and his final magnum opus, the Three Colours trilogy (1993-1994). Throughout his career, Kieślowski garnered numerous prestigious awards, including the Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize and FIPRESCI Prize, the Venice Film Festival Golden Lion, and the Berlin International Film Festival Silver Bear for Best Director. His exploration of the human condition, ethical choices, and the interplay of fate and chance left an indelible mark on global cinema, earning him Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay in 1995.

2. Early Life

Krzysztof Kieślowski's early life was marked by frequent relocations and a developing interest in the arts, leading him eventually to filmmaking.

2.1. Birth and Childhood

Krzysztof Kieślowski was born in Warsaw, Poland, on June 27, 1941, to Barbara (née Szonert) and Roman Kieślowski. His father, an engineer, suffered from tuberculosis, which necessitated the family's frequent moves to various small towns in search of treatment for his condition. This nomadic childhood exposed Kieślowski to diverse environments across Poland. He was raised in the Roman Catholic faith and maintained what he described as a "personal and private" relationship with God throughout his life. At the age of sixteen, he briefly attended a firefighters' training school but left after only three months.

2.2. Education

In 1957, without clear career aspirations, Kieślowski enrolled in the College for Theatre Technicians in Warsaw, a school managed by a relative. His initial ambition was to become a theatre director, but the theater department required a bachelor's degree, which he lacked. Consequently, he opted to study film as an interim step. After working as a theatrical tailor, Kieślowski applied twice to the renowned Łódź Film School, which counts notable filmmakers such as Roman Polanski and Andrzej Wajda among its alumni, but was rejected both times. To evade compulsory military service during this period, he briefly posed as an art student and underwent a drastic diet to be deemed medically unfit for service. Following several months of avoiding the draft, he was finally accepted into the school's directing department in 1964, on his third attempt. He attended the Łódź Film School until 1968, and despite state censorship and restrictions on foreign travel, he was able to travel extensively within Poland for his documentary research and filming. During his final year at film school, on January 21, 1967, he married his lifelong partner, Maria (Marysia) Cautillo. Kieślowski eventually lost interest in theatre, committing himself entirely to documentary filmmaking.

3. Career

Kieślowski's career spanned several distinct phases, evolving from a documentary filmmaker rooted in Polish social realities to an internationally acclaimed director of philosophical feature films.

3.1. Early Documentary Work

From 1966 to 1980, Kieślowski primarily focused on documentary filmmaking. His early works depicted the everyday lives of ordinary citizens-city dwellers, workers, and soldiers. Although not overtly political, his efforts to portray Polish life realistically often brought him into conflict with the authorities. For example, his 1971 television film Workers '71: Nothing About Us Without Us, which featured workers discussing the reasons behind the 1970 mass strikes in Poland, was only permitted to be screened in a heavily censored version. This experience led Kieślowski to question whether truth could be authentically conveyed under an authoritarian regime.

Following Workers '71, Kieślowski shifted his gaze to the authorities themselves in Curriculum Vitae (1975). This film ingeniously combined authentic documentary footage of Politburo meetings with a fictional narrative about an individual under state scrutiny. Despite Kieślowski's intent to convey an anti-authoritarian message, he faced criticism from some colleagues for seemingly cooperating with the government in its production. A pivotal moment for Kieślowski came during the filming of Station (1981), when some of his footage was nearly used as evidence in a criminal case. This incident, combined with the censorship of Workers '71, solidified his belief that fiction offered greater artistic freedom and a more truthful means of portraying everyday life than direct documentary. Consequently, he began to transition away from documentaries towards feature films.

3.2. Transition to Feature Films in Poland

Kieślowski's first non-documentary feature was Personnel (1975), made for television. This film, depicting the lives of technicians working on a stage production-a subject drawing from his own early college experiences-earned him first prize at the Mannheim Film Festival. His subsequent feature, The Scar (Blizna, 1976), was his first theatrical release. Both Personnel and The Scar were characteristic of social realism, featuring large casts and portraying the upheaval of a small town affected by a poorly planned industrial project. These films employed a documentary style, often utilizing non-professional actors, to depict daily life under an oppressive system without explicit commentary.

He continued to explore similar themes with Camera Buff (Amator, 1979), which won the grand prize at the 11th Moscow International Film Festival and the Golden Hugo Award at the Chicago International Film Festival in 1980. This film, along with Blind Chance (Przypadek, 1981), marked a shift in focus from broad community issues to the ethical choices confronting individual characters. The increasing repression in Poland during this period heavily impacted Kieślowski's work; Blind Chance, completed in 1981, faced severe censorship and was not released domestically until 1987, almost six years after its completion. Many of his early films were subjected to censorship, enforced re-shooting, or re-editing, with some being outright banned.

3.3. "Cinema of Moral Anxiety"

During this period, Kieślowski was closely associated with a loose movement of Polish directors, including Janusz Kijowski, Andrzej Wajda, and Agnieszka Holland, known as the "Cinema of moral anxiety" (Kino moralnego niepokojuCinema of moral anxietyPolish). This movement, prominent in the late 1970s and early 1980s, critically examined Polish society and individual ethics under the communist regime. Kieślowski's ties to these directors, particularly Holland, drew concern from the Polish government. His films from this era, such as Camera Buff and Blind Chance, are considered prime examples of this movement, emphasizing the ethical dilemmas faced by ordinary people within an oppressive system.

No End (Bez końca, 1984) stands as perhaps his most overtly political film, portraying political trials in Poland during martial law from the unique perspectives of a lawyer's ghost and his widow. Its stark depiction drew harsh criticism from the government, dissidents, and the church alike. Starting with No End, Kieślowski initiated key collaborations with two individuals: composer Zbigniew Preisner and trial lawyer Krzysztof Piesiewicz. Kieślowski met Piesiewicz while researching political trials for a planned documentary. Piesiewicz subsequently co-wrote the screenplays for all of Kieślowski's later films. Preisner composed the scores for No End and most of Kieślowski's subsequent films, with his music often playing a prominent narrative role, frequently attributed within the films to the fictional Dutch composer "Van den Budenmayer."

3.4. International Breakthrough

Kieślowski's international recognition soared with the creation of the Dekalog series and his subsequent European co-productions. His last four films, made primarily with funding from France and Romanian-born producer Marin Karmitz, marked his most commercially successful period. These films explored moral and metaphysical issues, mirroring themes from Dekalog and Blind Chance, but at a more abstract level, with smaller casts, more internalized narratives, and less emphasis on specific communities. Poland in these later works often appeared through the eyes of European outsiders.

3.5. The Dekalog Series

Dekalog (1988), a series of ten short films, was conceived for Polish television with financial support from West Germany. Each film is nominally based on one of the Ten Commandments and set within a Warsaw tower block. Originally, the ten one-hour-long episodes were intended for ten different directors, but Kieślowski ultimately directed all of them himself. The series quickly became one of the most critically acclaimed film cycles of all time. Episodes five and six were later expanded and released internationally as full-length feature films: A Short Film About Killing (Krótki film o zabijaniu, 1988) and A Short Film About Love (Krótki film o miłości, 1988), respectively. A Short Film About Killing earned significant accolades, including the European Film Award for Best Film, the Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize, and the FIPRESCI Prize in 1988. Kieślowski had also planned a full-length version of Episode 9, titled A Short Film About Jealousy, but exhaustion from directing the entire Dekalog series prevented him from undertaking what would have been his thirteenth film in less than a year. Famed American filmmaker Stanley Kubrick lauded Dekalog, noting Kieślowski and Piesiewicz's "very rare ability to dramatize their ideas rather than just talking about them," allowing audiences to "discover what's really going on rather than being told."

3.6. The Double Life of Veronique

In 1991, Kieślowski released The Double Life of Veronique (La double vie de Veronique), starring Irène Jacob. This film explores the mysterious connection between two identical women, one Polish and one French, who are unaware of each other's existence. It delves into themes of identity, fate, and parallel lives. The film achieved significant commercial success, which provided Kieślowski with the necessary funding for his ambitious final projects. The Double Life of Veronique received the FIPRESCI Prize and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, where Irène Jacob also won the Best Actress Award.

3.7. The Three Colours Trilogy

Following the success of The Double Life of Veronique, Kieślowski embarked on his final and most ambitious project: the Three Colours trilogy (1993-1994), comprising Blue, White, and Red. Each film explores one of the virtues symbolized by the French flag: liberty (Blue), equality (White), and fraternity (Red).

- Three Colours: Blue (Trois couleurs: Bleu, 1993) premiered at the Venice Film Festival, where it won the Golden Lion for Best Film, and its star Juliette Binoche received the Best Actress award. It delves into the themes of freedom and the process of overcoming profound grief.

- Three Colours: White (Trois couleurs: Blanc, 1994) was presented at the Berlin International Film Festival, where Kieślowski won the Silver Bear for Best Director. This film, a dark comedy, explores themes of equality, justice, and revenge.

- Three Colours: Red (Trois couleurs: Rouge, 1994) was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and later earned Kieślowski Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay in 1995. It concludes the trilogy by exploring fraternity, interconnectedness, and chance encounters, featuring Irène Jacob again in a lead role.

After the premiere of Three Colours: Red at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival, Kieślowski announced his retirement from filmmaking, citing exhaustion.

3.8. Posthumous Projects

At the time of his death, Kieślowski was collaborating with his longtime screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz on a second trilogy inspired by Dante's The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory. While originally intended for other directors, Kieślowski's untimely death left it unknown whether he would have directed them himself.

The only completed screenplay, Heaven, was adapted and directed by Tom Tykwer and premiered in 2002 at the Berlin International Film Festival. The scripts for Hell and Purgatory existed only as thirty-page treatments at the time of Kieślowski's passing. Piesiewicz subsequently completed these screenplays. Hell (L'Enfer), directed by Bosnian director Danis Tanović and starring Emmanuelle Béart, was released in 2005. The third part, Purgatory, a story about a photographer killed in the Bosnian war, remains unproduced.

Additionally, Jerzy Stuhr, an actor who starred in several of Kieślowski's films and co-wrote Camera Buff, directed his own adaptation of an unfilmed Kieślowski script titled The Big Animal (Duże zwierzę) in 2000.

4. Themes and Philosophy

Kieślowski's films are deeply infused with his personal worldview, which oscillated between pessimism and a profound humanism, consistently exploring moral quandaries and the unpredictable nature of existence.

4.1. Personal Beliefs and Worldview

Kieślowski characterized himself as a "pessimist," stating, "I always imagine the worst. To me, the future is a black hole." Friends, such as director Agnieszka Holland, noted that he often experienced depressive states. He was described as "conveying the sadness of a world-weary sage" and "a brooding intellectual and habitual pessimist." During a visit to the United States, he expressed amazement at "the pursuit of empty talk combined with a very high degree of self-satisfaction."

Despite being raised Roman Catholic, Kieślowski identified himself as an agnostic. However, he regarded the Old Testament and the Biblical Decalogue as an important moral compass during difficult times. In a 1995 interview at Oxford University, Kieślowski articulated his core artistic motivation: "It comes from a deep-rooted conviction that if there is anything worthwhile doing for the sake of culture, then it is touching on subject matters and situations which link people, and not those that divide people. There are too many things in the world which divide people, such as religion, politics, history, and nationalism. ... Feelings are what link people together, because the word 'love' has the same meaning for everybody. Or 'fear', or 'suffering'. We all fear the same way and the same things. And we all love in the same way. That's why I tell about these things, because in all other things I immediately find division." This sentiment underscores his humanistic outlook, emphasizing universal emotions over divisive ideologies.

4.2. Thematic Exploration in Film

Kieślowski's cinematic output consistently explored recurring themes that reflected his philosophical concerns. His films often delved into the intricacies of moral choices, particularly the ethical dilemmas faced by individuals under pressure. The interplay between fate and chance was a dominant motif, often depicting how seemingly random events could profoundly alter a character's life, as seen vividly in Blind Chance.

He meticulously examined the human condition, focusing on the inner lives and psychological states of his characters rather than external political or social commentary, especially in his later works. Existential questions about the meaning of life, the nature of good and evil, and the search for spiritual grounding permeated his narratives. His shift from large-scale social realism in early films like The Scar to more intimate, character-driven studies in Camera Buff and Blind Chance demonstrated his evolving focus on individual ethics within society. The Dekalog series served as a comprehensive exploration of modern moral dilemmas through the lens of the Ten Commandments, while the Three Colours trilogy abstracted universal virtues into compelling personal narratives.

5. Personal Life

Krzysztof Kieślowski shared a close personal life with his family throughout his career.

He married Maria (Marysia) Cautillo on January 21, 1967, during his final year at film school. Their marriage lasted until his death. They had one daughter, Marta, born on January 8, 1972.

6. Death

Krzysztof Kieślowski passed away on March 14, 1996, at the age of 54. His death occurred during open-heart surgery following a heart attack. This was less than two years after he had announced his retirement from filmmaking. He was interred in Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw, Poland. His grave is marked by a distinctive sculpture depicting the thumb and forefingers of two hands forming an oblong space, symbolizing the classic view through a film camera. This small sculpture is crafted from black marble and rests on a pedestal slightly over 3.3 ft (1 m) tall, with a slab bearing Kieślowski's name and dates situated below.

7. Legacy and Critical Reception

Kieślowski remains one of Europe's most influential and revered directors, whose works continue to be studied globally for their profound cinematic and philosophical contributions.

7.1. Critical Evaluation and Influence

Kieślowski is widely considered a leading figure of the "Cinema of moral anxiety" movement in Polish cinema during the 1970s and 1980s. His films from this period, characterized by their social realism and use of non-professional actors, focused on portraying life under the communist regime. Later in his career, he transitioned to more intimate explorations of individual ethics and the human condition. His ability to convey complex ideas through dramatic action, rather than explicit commentary, was highly praised by peers. Filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, in a foreword to the screenplay collection of Dekalog, lauded Kieślowski and his co-author Krzysztof Piesiewicz for their "very rare ability to dramatize their ideas" and their skill in allowing the audience to "discover what's really going on rather than being told."

Kieślowski's work is a staple in film studies programs at universities worldwide. In 2002, the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine ranked him at number two on its list of the top ten film directors of modern times. Total Film magazine also recognized his impact, placing him at No. 47 on its "100 Greatest Film Directors Ever" list in 2007. After Kieślowski's death, Harvey Weinstein, then head of Miramax Films (which distributed his last four films in the US), wrote a eulogy in Premiere magazine, calling him "one of the greatest directors in the world."

The profound impact of his films is also noted in specific instances; for example, director Cyrus Frisch stated that A Short Film About Killing was instrumental in the abolition of the death penalty in Poland.

7.2. Tributes and Commemorations

Kieślowski's life and work have been honored through various posthumous tributes. The 1993 book Kieślowski on Kieślowski, based on interviews with Danusia Stok, provides insights into his life and creative process in his own words. He is also the subject of a biographical film, Krzysztof Kieślowski: I'm So-So (1995), directed by Krzysztof Wierzbicki.

Since 2011, the Polish Contemporary Art Foundation In Situ has organized The Sokołowsko Film Festival: Hommage à Kieślowski, an annual event in Sokołowsko, where Kieślowski spent part of his youth. The festival commemorates his work with screenings of his films, alongside films by younger generations of Polish and European filmmakers, complemented by workshops, discussions, performances, exhibitions, and concerts. On June 27, 2021, Google celebrated his 80th birthday with a Google Doodle, further solidifying his global recognition.

8. Filmography

Krzysztof Kieślowski wrote and directed a total of 48 films during his career, including 11 feature films, 19 documentaries, 12 television films, and 6 short films.

8.1. Documentaries and Short Films

- The Face (Twarz, 1966) - also appeared as an actor

- The Office (Urząd, 1966)

- Tramway (Tramwaj, 1966)

- Concert of Requests (Koncert życzeń, 1967)

- The Photograph (Zdjęcie, 1968)

- From the City of Łódź (Z miasta Łodzi, 1968)

- I Was a Soldier (Byłem żołnierzem, 1970)

- Factory (Fabryka, 1971)

- Workers '71: Nothing About Us Without Us (Robotnicy '71: Nic o nas bez nas, 1971)

- Before the Rally (Przed rajdem, 1971)

- Between Wrocław and Zielona Góra (Między Wrocławiem a Zieloną Górą, 1972)

- The Principles of Safety and Hygiene in a Copper Mine (Podstawy BHP w kopalni miedzi, 1972)

- Gospodarze (1972)

- Refrain (Refren, 1972)

- The Bricklayer (Murarz, 1973)

- First Love (Pierwsza miłość, 1974)

- X-Ray (Przeswietlenie, 1974)

- Pedestrian Subway (Przejście podziemne, 1974)

- Curriculum Vitae (Życiorys, 1975)

- Hospital (Szpital, 1976)

- Slate (Klaps, 1976)

- From a Night Porter's Point of View (Z punktu widzenia nocnego portiera, 1977)

- I Don't Know (Nie wiem, 1977)

- Seven Women of Different Ages (Siedem kobiet w roznym wieku, 1978)

- Railway Station (Dworzec, 1980)

- Talking Heads (Gadające glowy, 1980)

- Seven Days a Week (Siedem dni tygodniu, 1988)

8.2. Feature Films and TV Dramas

| Year | English Title | Original Title | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Personnel | Personel | TV drama |

| 1976 | The Scar | Blizna | Film |

| 1976 | The Calm | Spokój | Film |

| 1979 | The Card Index | Kartoteka | Film |

| 1979 | Camera Buff | Amator | Film |

| 1981 | Short Working Day | Krótki dzień pracy | Film |

| 1985 | No End | Bez końca | Film |

| Produced in 1981 but released in 1987 | Blind Chance | Przypadek | Film |

| 1988 | Dekalog | Dekalog | TV miniseries |

| 1988 | A Short Film About Killing | Krótki film o zabijaniu | Film |

| 1988 | A Short Film About Love | Krótki film o miłości | Film |

| 1991 | The Double Life of Veronique | Podwójne życie Weroniki, La Double vie de Veronique | Film |

| 1993 | Three Colours: Blue | Trois couleurs: Bleu/Trzy kolory: Niebieski | Film |

| 1994 | Three Colours: White | Trois couleurs: Blanc/Trzy kolory: Biały | Film |

| 1994 | Three Colours: Red | Trois couleurs: Rouge/Trzy kolory: Czerwony | Film |

9. Awards and Nominations

Krzysztof Kieślowski received numerous accolades throughout his distinguished career, beginning with the Kraków Film Festival Golden Hobby-Horse in 1974. The following lists significant awards and nominations for his later works.

;A Short Film About Killing

- European Film Award for Best Film (1988) Won

- Cannes Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize (1988) Won

- Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize (1988) Won

- Cannes Film Festival Nomination for the Palme d'Or (1988)

- French Syndicate of Cinema Critics Award for Best Foreign Film (1990) Won

- Bodil Award for Best European Film (1990) Won

;Dekalog

- Bodil Award for Best European Film (1991) Won

- Venice Film Festival Children and Cinema Award (1989) Won

- Venice Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize (1989) Won

- National Board of Review Special Recognition (2000) Won

;The Double Life of Veronique

- Argentine Film Critics Association Silver Condor Nomination for Best Foreign Film (1992)

- Cannes Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize (1991) Won

- Cannes Film Festival Prize of the Ecumenical Jury (1991) Won

- Cannes Film Festival Nomination for the Palme d'Or (1991)

- French Syndicate of Cinema Critics Award for Best Foreign Film (1992) Won

- Warsaw International Film Festival Audience Award (1991) Won

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1991) Won

- Golden Globe Award Nomination for Best Foreign Language Film (1991)

;Three Colours: Blue

- César Award Nomination for Best Director (1994)

- César Award Nomination for Best Film (1994)

- César Award Nomination for Best Writing, Original or Adaptation (1994)

- Venice Film Festival Golden Ciak Award (1993) Won

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion Award (1993) Won

- Venice Film Festival Little Golden Lion Award (1993) Won

- Venice Film Festival OCIC Award (1993) Won

- Goya Award for Best European Film (1993) Won

- Golden Globe Award Nomination for Best Foreign Language Film (1993)

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1993) - Runner-up

- Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1993) - Runner-up

;Three Colours: White

- Berlin International Film Festival Silver Bear for Best Director (1994) Won

- European Film Award for Best Film (1994) Won (shared with Three Colours: Blue and Three Colours: Red)

;Three Colours: Red

- Academy Award Nomination for Best Director (1995)

- Academy Award Nomination for Best Original Screenplay (1995)

- BAFTA Film Award Nomination for Best Film not in the English Language (1995)

- BAFTA Film Award Nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay (1995)

- BAFTA Film Award Nomination for the David Lean Award for Direction (1995)

- Bodil Award for Best Non-American Film (1995) Won

- Cannes Film Festival Nomination for the Palme d'Or (1994)

- César Award Nomination for Best Director (1995)

- César Award Nomination for Best Film (1995)

- César Award Nomination for Best Writing, Original or Adaptation (1995)

- French Syndicate of Cinema Critics Award for Best Film (1995) Won

- Vancouver International Film Festival Most Popular Film (1994) Won

- Golden Globe Award Nomination for Best Foreign Language Film (1994)

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film (1994) - Runner-up

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Director (1994) - Runner-up

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Screenplay (1994) - Third place

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1994) Won

- Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1994) Won

- New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Director (1994) - Runner-up

- New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1994) Won

- Boston Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1994) Won

- Chicago Film Critics Association Award for Best Director (1994) Nomination

- Chicago Film Critics Association Award for Best Foreign Language Film (1994) Nomination

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Foreign Film (1994) Nomination