1. Biography

Kenji Mizoguchi's life journey was marked by early hardship and a relentless dedication to his craft, which ultimately led to his global recognition as a cinematic master.

1.1. Early life and family

Kenji Mizoguchi was born on May 16, 1898, in Hongō, Tokyo, as the second of three children to Zentaro Mizoguchi, a roofing carpenter, and his wife, Masa. His family initially belonged to the middle class, but their financial stability collapsed after his father's failed business venture selling raincoats to Japanese troops during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The family was plunged into debt, their home was seized, and they were forced to move to the downtown district of Asakusa. In an act driven by desperate poverty, Mizoguchi's older sister, Suzu (also known as Suzuko), seven years his senior, was effectively sold into the geisha profession through adoption. This profound familial sacrifice had a lasting impact on Mizoguchi, deeply influencing his lifelong thematic focus on the suffering and self-sacrifice of women. He developed a strong aversion to his father, whom he blamed for the family's financial ruin and for his abusive treatment of his mother and sister.

In 1905, Mizoguchi enrolled in Tagawa school and later transferred to Ishihama Elementary School in 1907, where he was a classmate of future screenwriter Matsutarō Kawaguchi. In 1911, due to his family's continued poverty, he was sent to live with an uncle in Morioka in northern Japan for about six months, where he completed primary school. Upon his return to Tokyo in 1912, his hopes for attending middle school were thwarted by his father's opposition. Soon after, he contracted crippling rheumatoid arthritis, which confined him to bed for about a year and left him with a distinctive limping gait for the rest of his life.

In 1913, his sister Suzu, now working as a geisha in Nihonbashi and supported by Viscount Matsudaira Tadamasa (who later made her his concubine and eventually his legal wife in 1947), helped him secure an apprenticeship as a designer for a yukata manufacturer in Asakusa. Feeling unfulfilled, he later apprenticed as a pattern artist. In December 1914, his mother passed away, further intensifying Mizoguchi's animosity towards his father. In 1916, he enrolled at the Aoibashi Yoga Kenkyuko art school in Akasaka, where he studied Western painting techniques for a year. During this time, he developed a keen interest in opera, assisting with set design and construction at the Royal Theatre in Akasaka. He also cultivated a taste for traditional Japanese storytelling, such as kōdan and rakugo, and read extensively, including works by Leo Tolstoy, Émile Zola, Guy de Maupassant, and Japanese authors like Kyōka Izumi and Nagai Kafū.

1.2. Entry into the film industry

After a period of bohemian living in Tokyo, sustained by his sister's financial support, Kenji Mizoguchi entered the burgeoning film industry. In 1918, his sister helped him find work as an advertisement designer for the Yuishin Nippon newspaper in Kobe, but he found the work unsuited to him and returned to Tokyo within a year. In 1920, through a friend who taught biwa, he met Nikkatsu Mukojima studio actor Tadashi Tomioka. With Tomioka's assistance and encouragement from up-and-coming director Osamu Wakayama, Mizoguchi joined the Nikkatsu studios in Mukojima, Tokyo, in May 1920, initially aspiring to be an actor. However, he was assigned as an assistant director to veteran director Tadashi Oguchi, performing various tasks including actor coordination and administrative duties.

His talent was recognized, particularly by director Eizo Tanaka, whom he assisted on the 1922 film Kyōya Erimise. In November 1922, a major staff shortage occurred at Nikkatsu after a mass exodus of actors and directors. In this void, Mizoguchi was recommended by Tanaka for promotion, making his directorial debut in February 1923 with Ai ni yomigaeru hi (The Resurrection of Love), based on a script by Wakayama. His second film, Kokyō (Hometown), released the same month, was severely censored due to its depiction of farmer uprisings against the wealthy. Despite these challenges, his early works, such as Haizan no uta wa kanashi (Song of Failure is Sad) in May and Kiri no minato (Foggy Harbour) in July, began to earn him recognition as a promising new director.

1.3. Silent film era

Following the devastating 1923 Great Kantō earthquake in September 1923, Mizoguchi's home was destroyed, and he, along with his family, took refuge at the Mukojima studio. He promptly filmed the aftermath of the earthquake and directed a dramatic film titled Haikyo no naka (In the Ruins). As the Mukojima studio closed, Mizoguchi and other staff members were transferred to Nikkatsu's Taishogun studios in Kyoto in November 1923. During this period, he worked at a rapid pace, often directing one film a month across various genres, though many of these were poorly received, marking what he considered a "slump period." His early works from this time included remakes of German Expressionist cinema and adaptations of Western literary figures like Eugene O'Neill and Leo Tolstoy.

In Kyoto, Mizoguchi immersed himself in traditional Japanese arts, studying kabuki and noh theatre, as well as traditional Japanese dance and music. His frequent visits to Kyoto and Osaka's tea houses, dance halls, and brothels led to a scandalous incident in May 1925, when a jealous prostitute and lover named Yuriko Ichijo attacked him with a razor, leaving a distinctive scar on his back. This highly publicized affair resulted in a three-month suspension from Nikkatsu. Despite the personal turmoil, his 1926 films, A Paper Doll's Whisper of Spring (Kaminingyō haru no sasayaki) and Passion of a Woman Teacher (Kyōren no onna shishō), were critically acclaimed for breaking his slump; the former was ranked 7th in the inaugural Kinema Junpo Best Ten list. Like most of his output from the 1920s and early 1930s, however, many of these silent films are now lost. By the end of the decade, Mizoguchi also directed several left-leaning "tendency films" that reflected contemporary socialist ideas, including Tokyo March and Metropolitan Symphony (Tokai kokyōkyoku), exploring social issues and the plight of women in capitalist society.

1.4. Transition to sound and early masterpieces

In 1930, with the advent of sound films in Japan, Mizoguchi directed his first part-talkie, Fujiwara Yoshie no Furusato, which was technically flawed. His first full sound film, Toki no ujigami (The Man of the Moment), was completed in 1932. He then left Nikkatsu, moving to Shinko Kinema, where he directed The Water Magician (1933) for Takako Irie's independent production. This film, an adaptation of Kyōka Izumi's story about a woman's sacrifice for a man's education, was highly praised and became a peak in his silent film era, notably featuring his nascent "one-scene-one-shot" camera technique.

His artistic maturity was truly realized with the 1936 diptych: Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion. These films, made for Masaichi Nagata's independent Daiichi Eiga-sha, earned widespread critical acclaim, with Sisters of the Gion topping the Kinema Junpo Best Ten and Osaka Elegy placing third. Mizoguchi himself considered these two films as the works through which he achieved artistic maturity. They depicted modern young women rebelling against their societal constraints, showcasing a stark realism, including the extensive use of the Kansai dialect, which critics hailed as a completion of Japanese cinematic realism. Osaka Elegy also marked the beginning of his long and fruitful collaboration with screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda, who would become his most trusted creative partner. In 1936, Mizoguchi was also a founding member of the Directors Guild of Japan, fostering friendships with other prominent directors like Yasujirō Ozu and Hiroshi Shimizu.

1.5. Wartime period

In 1939, Kenji Mizoguchi became the president of the Directors Guild of Japan (a position he held until 1942 and again from 1949 to 1955). This year also saw the release of The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums, a film widely considered his major pre-war masterpiece. It tells the story of a young woman who selflessly supports her partner's arduous journey to artistic maturity as a kabuki actor, often at the cost of her own well-being.

During World War II, Mizoguchi directed a series of films whose patriotic themes appeared to support the war effort. The most famous of these was The 47 Ronin (1941-42), an epic jidaigeki (historical drama) based on the classic samurai tale. There is scholarly debate regarding these films: some historians suggest Mizoguchi was pressured into making them, while others believe he acted voluntarily. Fellow screenwriter Matsutarō Kawaguchi, while generally holding Mizoguchi in high regard, even referred to him as an "opportunist" in a 1964 interview for Cahiers du Cinéma, suggesting he adapted his artistic choices to the prevailing political currents, moving from left to right and eventually embracing democracy. The production of The 47 Ronin was notably expensive due to Mizoguchi's meticulous attention to historical detail in its art direction and research, though it did not achieve significant commercial or critical success at the time.

A deeply personal tragedy struck Mizoguchi in December 1941, during the filming of The 47 Ronin Part 2. His wife, Chieko, whom he had married in 1927, was permanently hospitalized due to a mental illness. Mizoguchi erroneously believed she had contracted a venereal disease, which caused him immense distress. Despite his emotional turmoil, he immediately returned to the set to continue filming. Chieko, known for her strong will and her valuable, objective critiques of his work, never recovered and remained hospitalized for the rest of her life. Mizoguchi was profoundly affected, believing himself to be the cause of her illness. He later took Chieko's brother's widow, Fujio Tajima, as his de facto wife and adopted her two daughters.

The wartime period proved challenging for Mizoguchi's filmmaking, with several planned projects being canceled due to material shortages and military requisitions. In 1942, the Directors Guild of Japan was dissolved and merged into a government-controlled entity, with Mizoguchi becoming a director within this new structure. Films from this period, such as Danjūrō sandai (1944), Miyamoto Musashi (1944), and Meitō Bijomaru (1945), were generally considered failures, reflecting the difficult creative environment of the time.

1.6. Post-war career and international recognition

In the early post-war years, following Japan's defeat and subsequent occupation, Mizoguchi dedicated himself to a series of films that critically examined the oppression of women and their struggle for emancipation, setting these stories in both historical (primarily the Meiji era) and contemporary contexts. Most of these significant works were written or co-written by Yoshikata Yoda and frequently starred Kinuyo Tanaka, who became his regular leading actress until 1954. Their collaboration ended when Mizoguchi attempted to prevent Tanaka from directing her first film, leading to a professional falling out.

A notable exception during the Occupation was Utamaro and His Five Women (1946), an Edo period jidaigeki. This genre was generally viewed as inherently nationalistic or militaristic by the Allied censors, making Mizoguchi's ability to produce such a film a rare occurrence. His 1949 film Flame of My Love (Waga koi wa moenu) received particular acclaim for its unflinching portrayal of a young teacher who leaves her traditionalist background to pursue female liberation, only to discover that her supposedly progressive partner still harbors conventional male-dominant attitudes. While some of his immediate post-war films like Victory of Women (1946) and The Love of Sumako the Actress (1947) were initially not well-received, Women of the Night (1948) earned high praise, signifying his artistic comeback.

Despite a brief return to a slump with Waga koi wa moenu (1949), Mizoguchi's career saw a dramatic revitalization after his 1952 film The Life of Oharu. This film, which depicted the social decline of a woman banished from the Imperial court during the Edo era, was a commercial failure but garnered the prestigious International Award at the 13th Venice International Film Festival. This recognition significantly boosted Mizoguchi's confidence, effectively ending his prolonged post-war artistic slump.

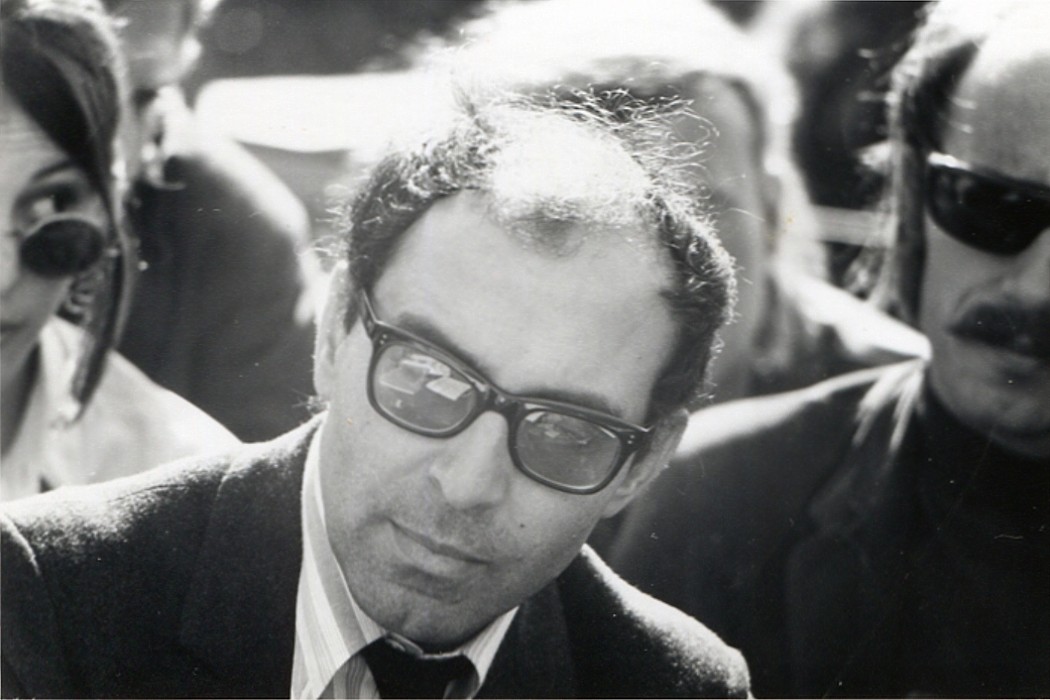

His subsequent works at Daiei, including the critically acclaimed Ugetsu (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954), solidified his international reputation. Both films explored the brutal impacts of war and violence on small communities and families, and each won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival in consecutive years, marking an unprecedented three-year winning streak for Mizoguchi at the festival. These successes earned him fervent admiration from prominent critics of the French New Wave, such as Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette. In between these historical dramas, Mizoguchi also directed A Geisha (1953), which shed light on the pressures faced by women working in Kyoto's post-war pleasure district.

1.7. Late career and final films

In his later career, Kenji Mizoguchi continued to push artistic boundaries, even venturing into color filmmaking. After his triumphal run at the Venice Film Festival, he joined Daiei as an exclusive director. In 1954, to research color film techniques, he traveled to the United States with Masaichi Nagata and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa. His first color film, Princess Yang Kwei Fei (1955), was a notable co-production with Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers. This was followed by his second color feature, Tales of the Taira Clan (1955), an adaptation of a novel by Eiji Yoshikawa. Although both films were commercial successes, Princess Yang Kwei Fei, submitted to the 16th Venice International Film Festival, did not secure a fourth consecutive award for Mizoguchi.

In September 1955, Mizoguchi was appointed to the board of directors at Daiei, becoming a prominent executive director in the studio. In October of the same year, he passed on the role of Director-General of the Directors Guild of Japan to Yasujirō Ozu. In November 1955, Mizoguchi was awarded the Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon, making him the first film director to receive this prestigious national honor. His final film, Street of Shame (1956), was a return to a contemporary, black-and-white setting, depicting the lives of prostitutes in a brothel within the Yoshiwara district, notably addressing the ongoing debate in the Japanese National Assembly about banning prostitution.

1.8. Personal life

Kenji Mizoguchi's personal life often stood in stark contrast to his demanding and often tyrannical professional persona. While on set, he was notoriously exacting, sometimes resorting to verbal abuse and harsh criticism of actors and staff. This led to him being called a "sadist," "tyrant," or "Gote-ken" (literally "complaining Ken") by those who worked under him. He pushed his actors to extreme lengths, insisting on dozens, sometimes even 80, rehearsals for a single shot, particularly in his favored long takes. He would demand intense preparation, such as reportedly forcing Kinuyo Tanaka to read every book in a library for a role. Anecdotes abound of his temper: he once hit actor Ichirō Sugai with a slipper and told him to "go to a mental hospital" for a botched line. He also famously shouted at actress Mitsuko Mito during the filming of Ugetsu, asking if she "had no experience" when she struggled to portray a scene of assault, and he harshly criticized veteran actress Takako Irie's performance, leading her to withdraw from a film.

Despite this demanding nature in his professional life, in private, Mizoguchi was described as weak-willed, shy, and introverted, almost a completely different person. He had a notable one-inch razor scar on his back, a permanent reminder of the 1925 incident where a jealous mistress attacked him. He reportedly told an assistant director upon seeing the scar, "You can't be surprised by this. Without this, you can't depict women."

Mizoguchi harbored a lifelong passion for old art and antiques, frequently visiting Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Nara to admire statues and collecting "getemono" (rustic, folk crafts). However, he was easily swayed by others' opinions and often acquired fake artifacts, earning him the nickname "Fake Goods Loving Wind Child" from director Tadashi Ōkubo. In his later years, he also developed an interest in writing seal script. He was a voracious reader, often consuming books late into the night, leading to a habit of oversleeping in the mornings.

Mizoguchi also struggled with alcoholism, which frequently led to violent and destructive outbursts. He was known to break objects and cause trouble when inebriated. Incidents include being tied to a stone lantern in a geisha house courtyard by a friend during a drunken stupor and, on another occasion, publicly urinating in a private room at a restaurant during a heated argument with author Sakunosuke Oda, only to sober up instantly when he realized the room belonged to Shintaro Shirai, to whom he owed a professional debt.

1.9. Death

Kenji Mizoguchi passed away from leukemia at the age of 58 on August 24, 1956, at the Kyoto Municipal Hospital. In the months leading up to his death, he had experienced symptoms such as his favorite sake losing its taste and bleeding gums. In May 1956, after developing a low fever and purple discoloration in his legs, he was admitted to the hospital. Although he received daily blood transfusions, his diagnosis of myeloid leukemia was kept from him, known only to a select few, including Daiei executive Masaichi Nagata. The day before he died, he reportedly left a final note expressing his desire to "enjoy working with the studio staff soon." His death mask was created by his art director, Hiroshi Mizutani.

His funeral, a company ceremony organized by Daiei, was held on August 30 at Aoyama Saijo in Tokyo. His grave is located at Honkōji, a sub-temple of Ikegami Honmon-ji in Tokyo, with a branch grave at Mangan-ji in Kyoto, where Masaichi Nagata had "World-renowned Director" carved into the side of his monument. News of Mizoguchi's passing reached the 17th Venice International Film Festival, which was underway at the time, and a tribute was paid before the screening of his final film, Street of Shame. At the time of his death, Mizoguchi was preparing to direct An Osaka Story, which was eventually filmed by Kōzaburō Yoshimura and released in 1957. A "Mizoguchi Award" for excellence in Japanese cinema was briefly established in his honor in August 1957 but was discontinued after only three awards.

2. Film Style and Themes

Kenji Mizoguchi's cinematic output is defined by a distinctive artistic vision, characterized by consistent thematic concerns and a unique visual and production methodology.

2.1. Thematic focus

Throughout his career, Kenji Mizoguchi consistently explored the lives and struggles of women, particularly focusing on their suffering, sacrifice, and fight for agency within the rigid confines of patriarchal and feudal Japanese society. He is often regarded as an early "feminist" director for his compassionate yet unsparing portrayals of women who are exploited, abused, or forced into desperate circumstances. Film scholar Ayako Saitō identifies two main archetypes of female protagonists in his films: those who are self-sacrificing and endure immense suffering for the sake of men's advancement or societal harmony, ultimately facing ruin (as seen in The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums, Ugetsu, and Sansho the Bailiff), and those who actively resist their oppressive fates, often "fallen women" such as prostitutes or geisha (examples include Osaka Elegy, Sisters of the Gion, Women of the Night, and Street of Shame).

In stark contrast to his nuanced female characters, the male figures in Mizoguchi's films are frequently depicted as weak, cowardly, or contributing to the women's suffering, with strong or heroic male roles being rare. This consistent portrayal highlights the societal structures that perpetuate women's oppression.

Mizoguchi's thematic approach was deeply rooted in a naturalistic realism, which he meticulously developed. This realism, combined with his aesthetic sensibility, aimed to expose the harsh realities of human existence. He demanded that his films capture "the smell of human bodies," emphasizing raw, unvarnished depictions of life. His commitment to realism was firmly established in films like Tōjin Okichi (1930) and reached its apex in the 1936 diptych, Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion. These films, which depicted the struggles of working women in Osaka and geisha in Gion, employed authentic regional dialects and a cold, detached perspective to create a profound sense of realism, earning critical praise for achieving a new height in Japanese cinema.

While his core focus remained on women, Mizoguchi was also attuned to contemporary social and political currents. His filmography demonstrates a willingness to engage with diverse genres and themes, including detective stories, German Expressionist influences, and socially critical "tendency films" with socialist leanings in the 1920s. During wartime, he produced patriotic films, reflecting the prevailing nationalistic mood, although his underlying interest in human fate and social critique persisted. In the post-war era, he directed "women's liberation films" like Flame of My Love (1949), directly addressing themes of female independence and emancipation in a rapidly changing Japan.

2.2. Visual style

Kenji Mizoguchi's background in painting profoundly influenced his distinctive visual style, resulting in films celebrated for their exquisite aesthetic beauty, often drawing comparisons to traditional Japanese art. His most defining visual techniques were the extensive use of long takes, particularly his signature "one scene, one shot" approach, and a deliberate avoidance of close-ups. He believed that breaking shots or using close-ups disrupted the natural flow of acting and allowed for "cheating" by obscuring imperfections, thus hindering the pursuit of a complete and authentic performance. Instead, he favored long shots and full shots to maintain a sense of distance and to emphasize the relationship between characters and their environment.

Mizoguchi first employed the "one scene, one shot" method in Tōjin Okichi (1930), refining it into a foundational element of his style by The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939). A famous example from the latter film is a more than five-minute-long mobile shot depicting a couple walking along a moat, captured from a low, upward-looking angle, demonstrating his mastery of fluid and intricate camera movements. He particularly favored crane shots, often utilizing them even when not strictly necessary, to achieve sweeping, continuous movements that imbued his scenes with a sense of visual poetry and depth. His meticulous mise-en-scène and precise composition, sometimes described as reminiscent of Sternberg's lighting and settings, ensured that each frame could stand as a complete and meaningful painting, carefully balancing formal beauty with profound emotional and thematic content. This emphasis on location and environment was a cornerstone of his approach, often becoming as significant as the characters themselves.

2.3. Production methods

Kenji Mizoguchi was renowned for his rigorous and perfectionistic approach to filmmaking, often pushing his actors and crew to their absolute limits. He demanded the highest standards, ceaselessly repeating scenes until he achieved his desired result, which sometimes led to him being labeled a "sadist" or "tyrant" by those who worked for him. Unlike many directors, he rarely gave explicit instructions, instead placing the burden of problem-solving on his cast and crew, waiting for them to deliver the performance or solution he sought. This method, while drawing out their maximum effort and creativity, was often accompanied by intense outbursts, including cursing and public humiliation.

Mizoguchi did not write his own scripts, relying on trusted screenwriters such as Yoshikata Yoda and Masashige Narusawa. His script development process was famously iterative; he would often harshly critique initial drafts, demanding multiple rewrites-sometimes more than ten-until the script met his approval. Even after a final script was completed, he would call the screenwriter to the set to revise dialogue, writing lines on a blackboard and having actors try them out for naturalness. He also eschewed storyboards, preferring to determine camera angles, positions, and shot lengths spontaneously during rehearsals, observing the actors' movements.

His commitment to realism extended to every aspect of his film's design, especially art direction and historical accuracy. He insisted on using authentic props and demanded extensive research from his staff on period customs and lifestyles. This meticulous approach to historical research began with Tōjin Okichi (1930) and became particularly pronounced in his "Meiji-mono" films of the 1930s, where he would spend a full day ensuring the precise detail of a single lamp. He often brought in outside experts, such as painter Kanshō Kaishō for historical customs and costumes, and architects for building reconstruction, most notably for the life-size recreation of the "Matsu no Rōka" (Pine Corridor) from Edo Castle in The 47 Ronin (1941-42), based on thorough historical documents.

Mizoguchi's direction of actors was particularly notorious. He would give minimal specific guidance beyond "just try it," but would make actors repeat scenes dozens of times until satisfied, forcing them to self-correct and improvise. He often asked actors if they were "reflecting," meaning responding naturally to their co-actors' dialogue and movements. His intense demands could turn volatile; he once hit actor Ichirō Sugai with a slipper in Flame of My Love (1949) and told him to "go to a mental hospital" for struggling with a line. He reportedly dismissed actress Reiko Kitami from The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939) for not cradling a child naturally, stating, "You're holding the child wrong. You haven't given birth, that's why." In Ugetsu (1953), he allegedly shouted at actress Mitsuko Mito, who was portraying a woman being assaulted, asking, "Don't you have any experience (of being assaulted)?" He even publicly insulted veteran actress Takako Irie during Princess Yang Kwei Fei (1955), criticizing her acting as "cat acting" (a pejorative term for theatrical, low-brow performances), which led to her withdrawal from the film.

Despite the intense pressure he exerted on his team, Mizoguchi applied the same rigor to himself. He maintained an unyielding focus on set, often remaining in the studio all day, even during lunch breaks, to preserve the atmosphere of tension and concentration. In his later years, he even brought a urinal to the studio to avoid leaving the set. This self-imposed intensity was so profound that during the filming of Ugetsu, he reportedly trembled so violently while gripping his seat on the crane that the camera itself vibrated, prompting cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa to insist he be removed from the crane.

2.4. "Mizoguchi Team"

Kenji Mizoguchi famously relied on a core group of trusted collaborators, often referred to as the "Mizoguchi Team," whose consistent involvement greatly contributed to his distinctive film style. He considered screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda and art director Hiroshi Mizutani to be his most indispensable partners, describing them as "like a part of my body" who could understand his vision without explicit verbal explanation. Yoda, who began working with Mizoguchi on Osaka Elegy in 1936, served as his primary screenwriter for approximately 20 years, becoming a "wife-like" creative partner. Other key writers in his team included Shuichi Hatamoto and his childhood friend Matsutarō Kawaguchi, whom Mizoguchi often consulted when facing creative blocks.

Among his cinematographers, Tatsuyuki Yokota and Shigeto Miki were long-time collaborators. In his later period, Kazuo Miyagawa became a particularly trusted cameraman, known for his ability to execute Mizoguchi's complex long takes and fluid camera movements. Composer Fumio Hayasaka provided scores for many of his significant works, while lighting technician Kenichi Okamoto and sound engineer Iwao Otani were also part of his reliable crew. The team's meticulous attention to detail extended to historical accuracy, with experts like painter Kanshō Kaishō frequently consulted for period customs and costumes.

Among his actors, Kinuyo Tanaka became an indispensable leading actress from Naniwa Onna (1940) onwards, starring in many of his most important post-war films. Mizoguchi held her in such high regard that there were even rumors of a romantic relationship between them after the war. Other frequent actors included Yoko Umemura, Kumeko Urabe, Ichiro Sugai, Eitaro Shindo, and Eiji Nakano, many of whom appeared in over a dozen of his films.

Mizoguchi also fostered a lineage of filmmakers who became his disciples. Tazuko Sakane, who worked as his assistant director, scriptwriter, and editor, later became the first female film director in Japan with her 1936 film Hatsu Sugata, for which Mizoguchi served as a supervisory director. Another prominent disciple was Kaneto Shindō, who began as Mizoguchi's art assistant on films like Aien kyo (1937) and later studied screenwriting under him. Shindō's debut film, Story of a Beloved Wife (1951), featured a character based on Mizoguchi, depicting the intense struggles of working under him. Shindō went on to write screenplays for Mizoguchi's films and consciously strove to create works with themes Mizoguchi "could never conceive." Shindō later directed the acclaimed documentary Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director (1975), which included extensive interviews with Mizoguchi's collaborators.

3. Legacy and Influence

Kenji Mizoguchi's contributions to cinema have left an indelible mark, influencing generations of filmmakers and consistently earning him recognition as one of the greatest directors in film history.

3.1. Critical reception

From the 1930s, Kenji Mizoguchi was considered one of Japan's foremost "maestros," and he remains a towering figure alongside Yasujirō Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, Mikio Naruse, and Keisuke Kinoshita as a representative of Japanese cinema's golden age. Japanese film critics particularly lauded his exceptional ability to portray women; film critic Akira Iwasaki famously stated, "No Japanese filmmaker after Mizoguchi has drawn women like him." Hideo Tsumura called him a "peerless master in capturing human, especially female, form at extremes of life's changes." Director Kon Ichikawa expressed deep admiration for Mizoguchi's profoundly "warm" gaze into humanity, despite his outwardly detached style. He was also highly praised as a "realist writer," with Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion being regarded as the works that established authentic realism in Japanese cinema. However, in the post-war period, some critics in Japan found his films' tempo slow due to his one-scene-one-shot technique and considered his themes to be outdated or pre-modern.

Internationally, Mizoguchi's reputation soared, particularly after his unprecedented achievement of winning major awards at the Venice International Film Festival for three consecutive years in the 1950s. He was enthusiastically championed by the young critics of the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, including Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, and Éric Rohmer, who later became key figures of the French New Wave. These critics saw Mizoguchi as a universal film artist, transcending national cinematic boundaries through his masterful use of mise-en-scène. Godard, a fervent admirer, hailed Mizoguchi as "one of the greatest filmmakers of all time," comparing him to revered masters like F. W. Murnau and Roberto Rossellini. Film historian David Thomson eloquently summarized Mizoguchi's unique contribution, stating, "The use of camera to convey emotional ideas or intelligent feelings is the definition of cinema derived from Mizoguchi's films. He is supreme in the realization of internal states in external views."

3.2. Influence on filmmakers

Kenji Mizoguchi's distinctive cinematic style, particularly his mastery of the long take and intricate mise-en-scène, profoundly influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers around the world. He was especially revered by the critics of the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, many of whom would later become central figures of the French New Wave. They actively promoted his work, with Ugetsu ranking first in Cahiers du Cinémas annual top ten list in 1959, and Sansho the Bailiff achieving the same distinction in 1960.

Jean-Luc Godard, a particularly fervent admirer, hailed Mizoguchi as "one of the greatest filmmakers" and paid direct homage to him in his own works. For example, the final panning shot to the sea in Godard's Contempt (1963) and Pierrot le Fou (1965) directly quotes the ending of Mizoguchi's Sansho the Bailiff. Godard even included a Japanese character named "Doris Mizoguchi" in his 1966 film Made in U.S.A.. Jacques Rivette explicitly acknowledged the influence of The Life of Oharu on his 1966 film The Nun.

Beyond the French New Wave, numerous other acclaimed directors have expressed deep admiration for Mizoguchi's work or have been visibly influenced by his techniques. These include Japanese contemporary Akira Kurosawa, American cinematic giants like Orson Welles and Martin Scorsese, and international masters such as Andrei Tarkovsky (who listed Ugetsu as one of his favorite films), Werner Herzog, Theo Angelopoulos (known for his similar use of long takes and fluid camera movements), Bernardo Bertolucci, Victor Erice, and Ari Aster. His innovative approach to conveying deep emotional states and exploring complex human conditions through meticulously crafted visual narratives continues to resonate and inspire filmmakers globally.

3.3. Awards and recognition

Kenji Mizoguchi received numerous prestigious awards and honors throughout his career, recognizing his profound impact on cinema both domestically and internationally.

| Year | Award | Category | Film / Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Ten (Japanese Film) | *Sisters of the Gion* (1st place) |

| 1952 | Venice International Film Festival | International Award | *The Life of Oharu* |

| 1953 | Venice International Film Festival | Silver Lion | *Ugetsu* |

| 1953 | Mainichi Film Awards | Best Film | *The Life of Oharu* |

| 1954 | Venice International Film Festival | Silver Lion | *Sansho the Bailiff* |

| 1954 | Blue Ribbon Awards | Best Director | *The Crucified Lovers* |

| 1955 | Art Encouragement Prize | *The Crucified Lovers* | |

| 1955 | Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon | (First film director to receive) | |

| 1956 | Order of the Sacred Treasure | Fourth Class | (Posthumous) |

| 1956 | Mainichi Film Concours | Special Award | (Posthumous) |

| 1956 | Blue Ribbon Awards | Japanese Cinema Culture Award | (Posthumous) |

3.4. Documentaries and tributes

Kenji Mizoguchi's enduring legacy has been honored through various documentaries, retrospectives, and critical acknowledgements. In 1975, Kaneto Shindō, who had worked as Mizoguchi's set designer and assistant director in earlier years, directed the acclaimed documentary Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director, followed by a book on his former mentor in 1976. Shindō had already paid homage to Mizoguchi in his autobiographical debut film, Story of a Beloved Wife (1951), where a character modeled on Mizoguchi appeared.

Mizoguchi's films continue to be regularly featured in "best film" polls globally. For instance, Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff have consistently appeared in Sight & Sound magazine's "The 100 Greatest Films of All Time," while The Life of Oharu, Ugetsu, and The Crucified Lovers have been ranked among the Kinema Junpo Critics' Top 200. In 2014, the Museum of the Moving Image and the Japan Foundation co-presented a retrospective featuring 30 of his extant films, which toured several cities in the United States, allowing new audiences to discover his profound cinematic contributions. Briefly, after his death, a "Mizoguchi Award" for excellence in Japanese cinema was established by the Sankei Shimbun in 1957 to recognize excellence in Japanese cinema, though it ceased after only three years.

4. Filmography

Kenji Mizoguchi directed approximately 90 to 100 films throughout his career. However, a significant portion of his early works, particularly from the silent film era, are now lost. The following chronological listings note the status of his films. Films marked with an "X" are lost, while others are considered extant. Color films are also specifically indicated.

4.1. Silent films

| Year | Japanese Title | Romaji Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | 愛に甦へる日 | Ai ni yomigaeru hi | X |

| 1923 | 故郷 | Kokyō | X |

| 1923 | 青春の夢路 | Seishun no yumeji | X |

| 1923 | 情炎の港 | Joen no chimata | X |

| 1923 | 敗残の唄は悲し | Haizan no uta wa kanashi | X |

| 1923 | 813 | 813 | X |

| 1923 | 霧の港 | Kiri no minato | X |

| 1923 | 夜 | Yoru | X |

| 1923 | 廃墟の中 | Haikyo no naka | X |

| 1923 | 血と霊 | Chi to rei | X |

| 1923 | 峠の唄 | Tōge no uta | X |

| 1924 | 哀しき白痴 | Kanashiki hakuchi | X |

| 1924 | 暁の死 | Akatsuki no shi | X |

| 1924 | 現代の女王 | Gendai no joō | X |

| 1924 | 女性は強し | Josei wa tsuyoshi | X |

| 1924 | 塵境 | Jinkyō | X |

| 1924 | 七面鳥の行衛 | Shichimenchō no yukue | X |

| 1924 | 伊藤巡査の死 | Itō junsa no shi | X (co-direction) |

| 1924 | さみだれ草紙 | Samidare zōshi | X |

| 1924 | 歓楽の女 | Kanraku no onna | X |

| 1924 | 恋を断つ斧 | Koi o tatsu ono | X (co-direction) |

| 1924 | 曲馬団の女王 | Kyokubadan no Jo | X |

| 1925 | 噫特務艦関東 | Ā tokumukan Kanto | X (co-direction) |

| 1925 | 無銭不戦 | Uchien Puchan | X |

| 1925 | 学窓を出でて | Gakusō o idete | X |

| 1925 | 大地は微笑む 第一篇 | Daichi wa hohoemu: Daiichibu | X |

| 1925 | 白百合は歎く | Shirayuki wa nageku | X |

| 1925 | 赫い夕陽に照されて | Akai yūki ni terasarete | X |

| 1925 | ふるさとの歌 | Furusato no uta | Earliest extant film |

| 1925 | 小品映画集 街のスケッチ | Shōhin eigashū: Machi no suketchi | X (co-direction) |

| 1925 | 人間 前後篇 | Ningen: zengohen | X |

| 1925 | 乃木将軍と熊さん | Nogi Taisho to Kuma-San | X |

| 1926 | 銅貨王 | Dōkaō | X |

| 1926 | 紙人形春の囁き | Kaminingyō haru no sasayaki | X |

| 1926 | 新説己が罪 | Shinsetsu ono ga tsumi | X |

| 1926 | 狂恋の女師匠 | Kyōren no onna shishō | X |

| 1926 | 海国男児 | Kaikoku danji | X |

| 1926 | 金 | Kane | X |

| 1927 | 皇恩 | Kōon | X |

| 1927 | 慈悲心鳥 | Jihishinchō | X |

| 1928 | 人の一生 人生万事金の巻 | Hito no isshō: Jinsei banji kane no maki | X |

| 1928 | 人の一生 浮世は辛いねの巻 | Hito no isshō: Ukiyo wa tsurai ne no maki | X |

| 1928 | 人の一生 クマとトラ再会の巻 | Hito no isshō: Kuma to tora saikai no maki | X |

| 1928 | 娘可愛や | Musume kawaiya | X |

| 1929 | 日本橋 | Nihonbashi | X |

| 1929 | 朝日は輝く | Asahi wa kagayaku | Few minutes preserved |

| 1929 | 東京行進曲 | Tōkyō kōshinkyoku | Few minutes preserved |

| 1929 | 都会交響楽 | Tokai kokyōkyoku | X |

| 1930 | 藤原義江のふるさと | Fujiwara Yoshie no furusato | Extant film |

| 1930 | 唐人お吉 | Tōjin Okichi | X |

| 1931 | しかも彼等は行く | Shikamo karera wa yuku | X |

| 1932 | 時の氏神 | Toki no ujigami | X |

| 1932 | 満蒙建国の黎明 | Manmō kenkoku no reimei | X |

| 1933 | 瀧の白糸 | Taki no shiraito | Extant film |

| 1933 | 祇園祭 | Gion matsuri | X |

| 1934 | 神風連 | Jinpu-ren | X |

4.2. Sound films

| Year | Japanese Title | Romaji Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | 愛憎峠 | Aizō tōge | X |

| 1935 | 折鶴お千 | Orizuru Osen | |

| 1935 | マリヤのお雪 | Mariya no Oyuki | X |

| 1935 | お嬢お吉 | Ojō Okichi | X (co-direction) |

| 1935 | 虞美人草 | Gubijinsō | |

| 1936 | 初姿 | Hatsu sugata | X |

| 1936 | 浪華悲歌 | Naniwa erejī | |

| 1936 | 祇園の姉妹 | Sisters of the Gion | |

| 1937 | 愛怨峡 | Aien kyō | |

| 1938 | 露営の歌 | Roei no uta | X |

| 1938 | あゝ故郷 | Aa kokyo | X |

| 1939 | 残菊物語 | Zangiku monogatari | |

| 1940 | 浪花女 | Naniwa onna | X |

| 1941 | 芸道一代男 | Geidō Ichidai Otoko | X |

| 1941 | 元禄忠臣蔵 前篇 | Genroku chūshingura Zenpen | |

| 1942 | 元禄忠臣蔵 後篇 | Genroku chūshingura Kōhen | |

| 1944 | 団十郎三代 | Danjūrō sandai | X |

| 1944 | 宮本武蔵 | Miyamoto Musashi | |

| 1945 | 名刀美女丸 | Meitō Bijomaru | |

| 1945 | 必勝歌 | Hisshōka | (co-direction) |

| 1946 | 女性の勝利 | Josei no shōri | |

| 1946 | 歌麿をめぐる五人の女 | Utamaro o meguru gonin no onna | |

| 1947 | 女優須磨子の恋 | Joyū Sumako no koi | |

| 1948 | 夜の女たち | Yoru no onnatachi | |

| 1949 | わが恋は燃えぬ | Waga koi wa moenu | |

| 1950 | 雪夫人絵図 | Yuki fujin ezu | |

| 1951 | お遊さま | Oyū-sama | |

| 1951 | 武蔵野夫人 | Musashino fujin | |

| 1952 | 西鶴一代女 | Saikaku ichidai onna | |

| 1953 | 雨月物語 | Ugetsu monogatari | |

| 1953 | 祇園囃子 | Gion bayashi | |

| 1954 | 山椒大夫 | Sanshō dayū | |

| 1954 | 噂の女 | Uwasa no onna | |

| 1954 | 近松物語 | Chikamatsu monogatari | |

| 1955 | 楊貴妃 | Yōkihi | (Color film) |

| 1955 | 新・平家物語 | Shin heike monogatari | (Color film) |

| 1956 | 赤線地帯 | Akasen chitai |