1. Overview

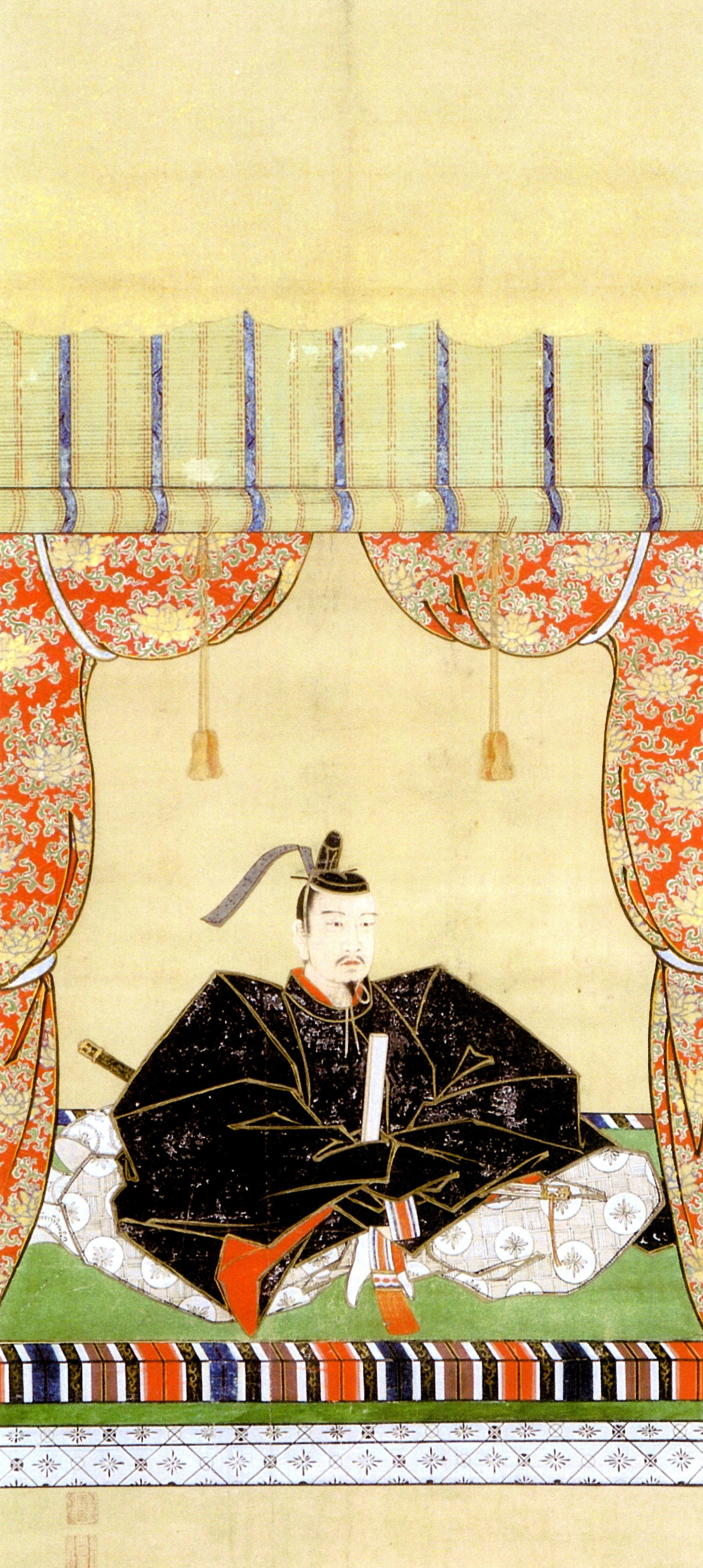

Katō Tadahiro (加藤忠広Katō TadahiroJapanese), born in 1601 and deceased on August 1, 1653, was a daimyō of the early Edo period in Japan. He succeeded his renowned father, Katō Kiyomasa, as the second lord of the Kumamoto Domain in Higo Province. Despite inheriting a significant domain, Tadahiro proved unable to effectively control his retainers or manage the domain's affairs, leading to significant political instability, including the Ushikata Umakata Disturbance. His perceived lack of governance ability and violations of shogunate regulations ultimately led to the confiscation of his domain in 1632, a pivotal event known as Kaieki (改易). Following this, he was exiled to Dewa Maruoka, where he spent the remaining 22 years of his life under the supervision of Sakai Tadakatsu, engaging in cultural pursuits until his death at age 53. Tadahiro's downfall is often seen as a reflection of the Tokugawa shogunate's efforts to centralize power and eliminate potential threats or administrative weaknesses among the daimyō, especially those associated with the former Toyotomi loyalists.

2. Life

Katō Tadahiro's life was marked by his inheritance of a powerful domain from a celebrated father, followed by a struggle to maintain control that ultimately led to the domain's confiscation and his long period of exile.

2.1. Early Life and Succession

Katō Tadahiro was born in 1601 as the third son of Katō Kiyomasa, a prominent military commander and daimyō. Although he had elder brothers, Torakuma and Kumanosuke (also known as Katō Tadamasa), both passed away prematurely, making Tadahiro the designated heir.

In 1611, upon the death of his father Kiyomasa, Tadahiro succeeded him as the head of the Katō clan and the second lord of the Kumamoto Domain. Being only 11 years old at the time, the Tokugawa shogunate imposed strict conditions on the Katō family's succession. These conditions were outlined in a nine-article edict, which included the abolition of several branch castles such as Minamata Castle, Uto Castle, and Yabe Castle (Aitōji Castle), the cancellation of outstanding land tax debts, and a reduction by half of the duties imposed on retainers, aimed at curbing expenses and preventing the burden from being transferred to the peasantry. Furthermore, the shogunate asserted its authority by reserving the right to handle personnel appointments for branch castle lords and determine the stipends for senior retainers. Later, in accordance with the shogunate's Ikoku Ichijo Rei (One Domain, One Castle) policy, other castles like Takanohara Castle, Ippō Castle, and Sashiki Castle were also ordered to be abolished, leaving only Kumamoto Castle and Mugishima Castle in existence.

During Tadahiro's early rule, the domain's administration was managed through a collegiate system by senior retainers, and Tōdō Takatora was said to have served as his guardian. The shogunate's intervention in abolishing branch castles and controlling personnel appointments was intended to regulate the semi-independent power wielded by senior retainers who had served as branch castle lords during Kiyomasa's era.

2.2. Domain Governance

Tadahiro's tenure as daimyō of the Kumamoto Domain was characterized by political instability and a notable lack of effective governance. Despite inheriting a significant territory on the island of Kyushu, which encompassed matters of governance, taxation, and defense with a retinue of samurai, Tadahiro struggled to consolidate his authority. His youth and perceived lack of leadership meant he could not fully control his vassals, leading to internal conflicts.

A significant event during his rule was the Ushikata Umakata Disturbance, a conflict among his senior retainers that further destabilized the domain's administration. This internal strife led to widespread political confusion. Contemporary observers, such as Hosokawa Tadaoki, who ruled the neighboring Kokura Domain and diligently gathered intelligence on surrounding daimyō, noted Tadahiro's behavior as "insane" and viewed him with caution. Tadaoki's son, Hosokawa Tadatoshi, also investigated the situation, reporting that "the governance of Higo Province is in disorder, and its conduct is chaotic," indicating a critical state of affairs within the domain. Additionally, issues related to conflicts between his principal wife and his concubines, specifically the "matter of women," are believed to have contributed to the internal turmoil.

The challenges in his governance were not merely a result of his personal failings but also inherited problems from his father, Kiyomasa. While Kiyomasa was known for his land reclamation and hydraulic engineering projects, the mobilization system established for the Korean campaigns, and subsequently for the Battle of Sekigahara and various public works projects by the shogunate, continued to burden the peasantry with heavy taxes and frequent mobilizations, leading to the exhaustion of the domain's resources. Kiyomasa had also granted significant authority to his branch castle lords, and when the young Tadahiro succeeded him, the shogunate attempted to directly intervene to curb their power. However, these attempts at control proved difficult, contributing to internal conflicts and the stagnation of domain policies. Furthermore, the death of key retainers who supported Kiyomasa, such as Ōki Kaneaki (who committed junshi) and Shimokawa Matazaemon (who managed internal affairs in Kumamoto), left Tadahiro with a vulnerable administrative structure, which exacerbated the Ushikata Umakata Disturbance.

2.3. Confiscation of Domain (Kaieki)

The culmination of Katō Tadahiro's administrative struggles and personal conduct issues was the Kaieki, or confiscation of his domain, by the Tokugawa shogunate. On May 22, 1632, while en route to Edo for his mandatory attendance (an integral part of the sankin-kōtai system), Tadahiro was stopped at Shinagawa-juku and denied entry into the capital. The formal announcement of his domain's confiscation was delivered by the shogunate's envoy, Inaba Masakatsu, at Ikegami Honmon-ji Temple.

Upon receiving the news, there were initial preparations for a siege by Tadahiro's retainers in Kumamoto. However, a letter personally written by Tadahiro reached the domain, leading to the peaceful surrender of Kumamoto Castle. Following the confiscation, Tadahiro was placed under the supervision of Sakai Tadakatsu, the lord of the Shōnai Domain in Dewa Province.

2.4. Life in Exile

After the confiscation of his domain, Katō Tadahiro began a 22-year period of exile in Dewa Maruoka. He was granted a nominal stipend of 10,000 koku for his lifetime, though the actual annual revenue collected by the Shōnai Domain's administrators was less than 3.00 K koku. He departed Edo with a retinue of about 50 people, including his mother, Seioin (正応院SeioinJapanese), a concubine, a wet nurse, ladies-in-waiting, and 20 retainers. He also arranged for his grandmother (Seioin's mother), who had remained in Higo, to join him in Maruoka. The 20 retainers who accompanied him primarily served his personal needs, as the local administrators from Shōnai Domain handled matters of land tax collection.

Despite Tokugawa Iemitsu's reported strong animosity towards Tadahiro, which led to the shogunate instructing the Shōnai Domain via Senior Council (Rōjū) member Matsudaira Nobutsuna to allocate "a bad place" in Shōnai for his confinement, Tadahiro's life in exile was relatively free and enriched by cultural pursuits. This was partly due to supplementary rice provisions from the Shōnai Domain and financial support from his former retainers residing at Honkoku-ji Temple in Kyoto, where some of the Katō family's assets had been moved after the confiscation.

During his exile, Tadahiro devoted himself to literature, music, calligraphy, and poetry. He compiled a collection of 319 poems composed over approximately one year from the start of his exile, titled Jin Taishū (塵躰集Japanese). His poems often referenced well-known phrases from the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu and showed a strong influence from The Tales of Ise, reflecting a sense of sorrow for his diminished status, akin to Ariwara no Narihira's journey to the East. He also frequently quoted The Tale of Genji, seemingly projecting himself onto Hikaru Genji. Tadahiro found solace in playing musical instruments like the shakuhachi and frequently visited Kinpu Shrine for ritual bathing. Surrounded by his mother, grandmother, concubine, and female attendants in the inner quarters, and young pages in the outer, he led a quiet yet fulfilling life, writing poetry, studying classics, playing music, and appreciating nature.

Notably, while Jin Taishū contains poems about his father Kiyomasa, his concubine Hōjōin (法乗院Japanese), and his elder sister Ama Hime, there are no poems dedicated to his principal wife, Suhoin, or his eldest son, Mitsuhiro. This omission provides a glimpse into the strained relationship he had with Suhoin, who was a granddaughter of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

After 20 years in exile, Tadahiro's mother passed away in June 1651. Two years later, in 1653, Tadahiro himself died at the age of 53. In accordance with his wishes, his remains were interred alongside his mother's, who had been buried on the premises of their residence, at Honju-ji Temple (present-day Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture). Their graves were constructed side-by-side. One of his loyal retainers, Katō Mondo, shaved his head and became a monk to serve as Tadahiro's grave keeper. Six of Tadahiro's former retainers who wished to continue serving were employed by the Shōnai Domain, and their descendants continued to serve the domain until the Bakumatsu period.

3. Reasons for Confiscation

The confiscation of Katō Tadahiro's domain, known as Kaieki, was a complex event that has been the subject of various historical interpretations. While traditional theories often cited conspiracy or his family's loyalty to the Toyotomi clan, modern historical research has largely refuted these claims, pointing to a combination of his perceived administrative incompetence, internal domain instability, and specific violations of shogunate laws.

3.1. Historical Allegations and Rebuttals

Several historical theories traditionally attributed the Kaieki to specific alleged transgressions, but these have been challenged by recent scholarship:

- Alleged Involvement in Conspiracy with Katō Mitsuhiro**: One theory suggested that his eldest son, Katō Mitsuhiro, forged a petition of rebellion (renpanjō) with the names and personal seals of various daimyō as a mere game. While this "certain document incident" involving Mitsuhiro did occur and played a role in the shogunate's scrutiny, research indicates it was not a genuine conspiracy for rebellion by Tadahiro or other daimyō.

- Conspiracy with Tokugawa Tadanaga**: It was widely believed that Tadahiro was implicated in the downfall of Tokugawa Tadanaga, the younger brother of Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, who was also stripped of his domain and ultimately forced to commit seppuku. However, no primary sources provide evidence of a special relationship between Tadahiro and Tadanaga. In fact, while Tadanaga was denied entry into Edo during Tokugawa Hidetada's illness, Tadahiro continued to receive gifts like ayu (sweetfish) and cranes from the shogunal family, indicating ongoing positive relations. Furthermore, Tadanaga's confiscation occurred *after* that of the Katō family, making a direct causal link unlikely.

- Status as a Toyotomi-Loyal Daimyō**: Due to his father Kiyomasa's close association with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the Katō family was often perceived as deeply loyal to the Toyotomi. This theory suggested that the shogunate, aiming to eliminate any remaining Toyotomi influence, targeted Tadahiro. However, the Katō clan's stable position as daimyō was solidified only after Kiyomasa's marriage alliance with Tokugawa Ieyasu's adopted daughter and his subsequent loyal service to Ieyasu after the Battle of Sekigahara, even before Ieyasu became Shogun. Kiyomasa's daughters were also married into prominent Tokugawa-allied families (one to Sakakibara Yasumasa's son, another to Ieyasu's tenth son, Tokugawa Yorinobu), indicating deep ties to the Tokugawa. Kiyomasa was even allowed to attend the Nijō Castle meeting as Yorinobu's father-in-law, suggesting he was seen as a crucial intermediary between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa. This historical context refutes the idea that Tadahiro was singled out purely for Toyotomi loyalty.

- Shogunate's Premeditated Conspiracy**: Another theory posited that the Kaieki was a deliberate plot by the shogunate from the outset. However, records show that after the discovery of Mitsuhiro's "certain document incident," the shogunate conducted careful investigations, informed other daimyō about the proceedings, and considered the explanations of both Tadahiro and Mitsuhiro, as well as the opinions of the three Tokugawa branch families (Gosanke), before making its decision. This suggests that the confiscation was not a predetermined outcome.

3.2. True Causes of Confiscation

Modern historical research indicates that the true reasons for Katō Tadahiro's downfall were multifaceted, rooted in his administrative failings and specific acts of defiance against shogunate regulations.

- Lack of Governance Ability and Internal Instability**: The primary catalyst was the "certain document incident" involving his son, Mitsuhiro. This event brought Tadahiro's general lack of governance ability and misconduct to the attention of the shogunate, who perceived the "Higo domain's administration as chaotic and its conduct disorderly." This perceived "gross impropriety" (shoji busahō) was a major factor. As detailed in the "Domain Governance" section, the underlying issues included his inability to control his retainers, internal conflicts like the Ushikata Umakata Disturbance, and the general stagnation of domain policies. The deaths of key retainers who had supported Kiyomasa had also left Tadahiro with a vulnerable administrative structure, which exacerbated these problems.

- Violation of Buke Shohatto (Laws for the Military Houses)**: A crucial specific transgression was Tadahiro's violation of Article 8 of the Buke Shohatto. He brought his concubine, Hōjōin, and their two children into his domain without the shogunate's permission. This was interpreted as an attempt to establish marital ties with someone outside the shogunal family's approval, a direct defiance of the shogunate's strict controls over daimyō's marital and familial alliances.

- Personal Conduct and Disregard for Tokugawa-Lineage Wife**: Further contributing to his downfall was his personal conduct, particularly his poor treatment of his principal wife, Suhoin, who was a granddaughter of Tokugawa Ieyasu and thus had direct ties to the shogunal family. He was seen as neglecting Suhoin and their eldest son, Mitsuhiro, in favor of his concubine, Hōjōin, and their two children. This issue, referred to as the "matter of women," was explicitly mentioned in contemporary records, such as letters from Hosokawa Tadaoki, as a reason for the Kaieki, indicating that Tadahiro's attitude towards his Tokugawa-blood wife was deemed "outrageous."

- Complacency from Past Escapes**: Some historians suggest that Tadahiro's and Mitsuhiro's reckless behavior stemmed from a sense of complacency. Tadahiro had previously avoided confiscation despite the Ushikata Umakata Disturbance, which may have led him to underestimate the severity of his actions. Mitsuhiro, as a great-grandson of Hidetada, might have felt entitled due to his high status, leading him to initiate the "certain document incident" without fully grasping its gravity.

In essence, while the shogunate thoroughly investigated various allegations, the confiscation was ultimately a result of Tadahiro's perceived lack of governing capability, the severe internal instability in his domain, and his specific violations of the Buke Shohatto regarding his personal family matters, all of which reflected his inability to properly manage a significant domain under the centralized authority of the Tokugawa shogunate.

4. Family and Descendants

Katō Tadahiro's family life, particularly after the confiscation of his domain, was marked by tragedy and the contentious continuation of his lineage.

Tadahiro's parents were Katō Kiyomasa and his mother, Seioin (正応院Japanese, died 1651), who was the daughter of Tamame Tanba-no-kami.

His principal wife was Suhoin (崇法院Japanese, 1602-1656), also known as Yorihime or Kotohime. She was an adopted daughter of Tokugawa Hidetada and the biological daughter of Gamō Hideyuki. Notably, Suhoin did not accompany Tadahiro into exile after his domain's confiscation, likely due to the strained relationship between them and her Tokugawa lineage.

Tadahiro had several children:

- Katō Mitsuhiro** (加藤光広Japanese, 1614-1633): His eldest son, also known as Kōshō. After the Kaieki, Mitsuhiro was placed under the custody of Kanamori Shigeyori, the lord of the Hida-Takayama Domain. He was granted a monthly stipend of 100 koku and confined to Tenjō-ji Temple. However, he died just one year later, on July 16, 1633, in exile, with theories suggesting both suicide and poisoning.

- Fujieda Masayoshi** (藤枝正良Japanese): His second son, also known as Seijuro. He took the surname Fujieda and was placed under the care of his mother, Tadahiro's concubine Hōjōin, and the Sanada clan. Masayoshi committed suicide, following his father's fate.

- Kamehime** (亀姫Japanese), also known as Kanjūin (献珠院Japanese): A daughter, she was granted permission to leave exile six years after Tadahiro's death. Through the efforts of her aunt, Yōrinin (Tadahiro's elder sister and the principal wife of Tokugawa Yorinobu), she married Abe Masashige, the fifth son of Abe Masayuki, a hatamoto. However, Masashige died at age 32, shortly after inheriting his family headship, approximately three years into their marriage.

The formal line of the Katō family was considered to have ended with the death of Masayoshi, and their territories were confiscated. However, a memorandum submitted to the Shōnai Domain at the time of Tadahiro's death requested that his belongings be sent to a surviving son and daughter in Numata. Although difficult to definitively prove, this suggests that the possibility of Tadahiro having unofficial descendants who continued his line is acknowledged.

It is believed that Tadahiro fathered two children (Kumatarō Mitsuaki and an unnamed daughter) during his exile in Maruoka, though these births could not be officially recognized. Their descendants are said to have continued as the Katō Yozaemon (or Yoichizaemon) family, a prominent shōya (village headman) family with a standing equivalent to 5.00 K koku. This lineage notably received the honor of a visit from Emperor Meiji to their residence during the Meiji period. The main branch of this family, however, ended with the death of Katō Sechi (加藤セチJapanese, 1893-1989), Japan's first married woman to earn a doctorate in science. Nevertheless, other branch families, including the Katō Yoichizaemon family, continued the lineage primarily in Yamagata Prefecture and across Japan.

5. Character and Anecdotes

Katō Tadahiro's character is often depicted as naive and incompetent, a stark contrast to his formidable father, Katō Kiyomasa. However, some anecdotes also reveal a more humanistic and considerate side to his personality.

One widely circulated anecdote, recorded in Kanzawa Tokō's Okina-gusa (翁草Japanese), illustrates his perceived naivety. One night, Tadahiro summoned his elderly retainer, Iida Naokage, and declared, "I wish to possess strength. If I had the strength of ten men, I could wear two heavy suits of armor. Then, no arrow or bullet could ever pierce me." Iida reportedly cautioned him, saying, "Your father, Kiyomasa-kō, went to many battles wearing light armor and never once sustained an injury. Even with precautions, injuries can occur by fate. Such strength is not necessary." After leaving Tadahiro's presence, Iida sighed, lamenting, "This will be the end of the Katō house." This story serves to highlight Tadahiro's alleged lack of practical judgment compared to his father.

Another popular tale claims that Tadahiro secretly moved his father Kiyomasa's remains to Maruoka and held a memorial service there. However, modern research by Fukuda Masahide challenges this anecdote, pointing out that Kiyomasa's body was buried deep beneath Jōchi-byō (Kiyomasa's mausoleum). Furthermore, after the Katō family's confiscation, Tokugawa Iemitsu ordered Hosokawa Tadatoshi, who entered Higo, to protect Jōchi-byō, making exhumation nearly impossible. The circumstances surrounding the alleged discovery of the remains are also considered to be contrived, casting doubt on the veracity of this story.

A local legend in the Shōnai region of Dewa Province connects Tadahiro to the "Sumi Kite" (すみ凧Japanese), a traditional kite with a red circle and arabesque patterns. It is believed that the design, which resembles the Katō family's jabara-mon (snake's eye crest), remained in the region due to Tadahiro's exile there.

Despite his shortcomings, an anecdote from Hirose Kyokuso's Kūkei Sōdō Zuihitsu (九桂草堂随筆Japanese) portrays Tadahiro's considerate nature. After being exiled to Shōnai, he sent a type of bean to an acquaintance in Higo Province, noting that this variety was not found in the western provinces. This act, leading to the spread of these beans in western Japan, suggests that Tadahiro maintained an interest in agriculture and showed thoughtfulness towards others, offering a glimpse of his more humanistic side.

6. Legacy and Assessment

Katō Tadahiro's legacy is predominantly defined by the downfall of his domain, a significant event in the early Edo period that underscored the Tokugawa shogunate's consolidating power and its intolerance for internal weaknesses within its daimyō. His rule is primarily assessed as contributing to the administrative stagnation and internal conflicts that culminated in the Kaieki. The problems he faced were partly inherited from his father, Kiyomasa, whose policies of heavy taxation and constant mobilization for military campaigns and public works had already exhausted the domain's peasantry. Tadahiro's inability to control his powerful retainers and resolve internal disputes, such as the Ushikata Umakata Disturbance, further exacerbated these issues. The loss of key administrative and diplomatic figures upon Kiyomasa's death also left Tadahiro with a fragile system.

The confiscation of his domain under the pretext of his "lack of governance ability" and "gross impropriety," alongside his violations of the Buke Shohatto and personal conduct issues, served as a stark example of the shogunate's centralized control. It demonstrated that even powerful daimyō families with historical ties to the Toyotomi clan (and later to the Tokugawa) were not immune to punitive measures if their rule was deemed unstable or if they failed to adhere strictly to shogunate regulations. While some historical accounts from the English source broadly mention his "military leadership, diplomatic finesse, and cultural patronage" and his "strategic brilliance," these positive assessments largely contradict the more detailed Japanese historical records that paint a picture of administrative challenges and a lack of effective governance.

Tadahiro's life and the eventual dissolution of the Katō clan's direct control over Kumamoto reflect the broader political climate of the early Edo period, where the shogunate systematically sought to stabilize its rule by eliminating potential threats and ensuring strict compliance from regional lords. His legacy, therefore, serves as a significant case study in the shogunate's policies of control and the consequences of administrative weakness during a period of profound social and political transformation in Japan. While his later life in exile suggests a retreat into cultural pursuits, his impact on society is largely viewed through the lens of his administrative failures and the subsequent restructuring of the Kumamoto Domain under the Hosokawa clan.