1. Life

Katherine Anne Porter's life was marked by early challenges, a persistent pursuit of her literary calling, and a long, acclaimed career that saw her recognized as a major voice in American letters.

1.1. Early childhood and background

Katherine Anne Porter was born Callie Russell Porter on May 15, 1890, in Indian Creek, Texas, to Harrison Boone Porter and Mary Alice (Jones) Porter. Her mother died in 1892, two months after giving birth, when Porter was two years old. Following this tragedy, her father moved his four surviving children to live with his mother, Catherine Ann Porter, in Kyle, Texas. The profound influence of her grandmother led Porter to later adopt her name. In 1901, when Porter was eleven, her grandmother passed away while taking her to visit relatives in Marfa, Texas.

After her grandmother's death, the family resided in various towns across Texas and Louisiana, staying with relatives or in rented accommodations. Porter attended free schools wherever the family lived, and for one year in 1904, she enrolled in the Thomas School, a private Methodist institution in San Antonio, Texas. This marked her only formal education beyond grammar school. Porter was known for her enthusiasm for genealogy and family history, spending years constructing an embellished version of her ancestry, including claims of descent from Daniel Boone and a companion of William the Conqueror. Most of these genealogical connections were unfounded, and her family regarded them as part of her character as an "accomplished raconteur." Despite her focus on family history, Porter did not identify her distant familial connection to Lyndon B. Johnson, the 36th President of the United States, whose grandmother was the sister of Porter's uncle-by-marriage.

1.2. Young adulthood and early activities

In 1906, at the age of 16, Porter left home and married John Henry Koontz in Lufkin, Texas. She subsequently converted to Roman Catholicism, his religion. Koontz, from a wealthy Texas ranching family, was physically abusive; during one incident, he threw her down the stairs while drunk, breaking her ankle. They officially divorced in 1915. In the same year, as part of her divorce decree, she formally changed her name to Katherine Anne Porter.

In 1914, Porter briefly escaped to Chicago, where she worked as an extra in movies. She then returned to Texas, performing as an actress and singer on the small-town entertainment circuit. In 1915, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and spent the next two years in sanatoria. It was during this period that she decided to pursue writing as a career, though it was later discovered she had bronchitis, not tuberculosis. In 1917, she began writing for the Fort Worth Critic, where she critiqued dramas and wrote society gossip. Prior to 1918, Porter had also been married to T. Otto Taskett and Carl Clinton von Pless, both marriages ending in divorce. In 1918, she wrote for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver, Colorado. While there, she nearly died during the 1918 flu pandemic. After months in the hospital, she was discharged frail and completely bald. When her hair regrew, it was white and remained so for the rest of her life. This harrowing experience was later reflected in her trilogy of short novels, Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939).

Porter's personal life also included significant emotional and physical challenges. In 1924, she had an affair with Francisco Aguilera that resulted in a stillbirth in December of that year. Biographers also suggest that Porter experienced several miscarriages and had an abortion. During the summer of 1926, she contracted gonorrhea from an English painter named Ernest Stock, which led to a hysterectomy in 1927, ending her hopes of having children. Despite this, her letters to lovers sometimes intimated menstruation. She once confided to a friend, "I have lost children in all the ways one can."

1.3. New York and Mexico: First literary works

In 1919, Porter moved to Greenwich Village in New York City, supporting herself through ghost writing, writing children's stories, and conducting publicity work for a motion picture company. Her year in New York had a politically radicalizing effect on her. In 1920, she relocated to Mexico to work for a magazine publisher, where she became acquainted with members of the Mexican leftist movement, including the renowned artist Diego Rivera. However, Porter eventually grew disillusioned with the revolutionary movement and its leaders. Throughout the 1920s, she was intensely critical of religion, a stance she maintained until the final decade of her life, when she re-embraced the Roman Catholic Church.

Between 1920 and 1930, Porter frequently traveled between Mexico and New York City, during which time she began publishing short stories and essays. Her first published story, "María Concepción", appeared in The Century Magazine. In 1930, she published her first short-story collection, Flowering Judas and Other Stories. An expanded edition of this collection, released in 1935, received such widespread critical acclaim that it virtually secured her place in American literature. The collection's title story, Flowering Judas, explored the psychological state of a female revolutionary. Porter also gained recognition for her works set in Mexico and the American South, such as The Farm (1924), which depicted Russian filmmakers, and Noon Wine (1937), which addressed themes of suicide and murder. These works led to her being recognized as a prominent Southern writer, alongside figures like William Faulkner.

1.4. Acclaimed writing career and teaching

From the 1930s through the 1950s, Katherine Anne Porter established a prominent reputation as one of America's most distinguished writers. Despite her critical success, her relatively limited literary output and sales meant she often relied on grants and advances for financial support during this period.

In the 1930s, she spent several years in Europe, continuing to publish short stories. She married Eugene Pressly, a writer, in 1930. After returning from Europe in 1938, she divorced Pressly and married Albert Russel Erskine, Jr., a graduate student. Their marriage ended in 1942, reportedly after Erskine discovered Porter's true age and that she was 20 years his senior. In 1941, while at the artists' retreat Yaddo, Porter found her future home in Malta, which she named "South Hill." She resided there for several years before selling the property in 1946.

Porter's literary standing was further recognized in 1943 when she was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. She served as a writer-in-residence at several prestigious institutions, including the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan, and the University of Virginia. Between 1948 and 1958, she taught at Stanford University, the University of Michigan, Washington and Lee University, and the University of Texas. Her unconventional teaching style made her highly popular among students. In 1959, the Ford Foundation awarded Porter a grant of 26.00 K USD over two years.

Her works were also adapted for other media. Three of her stories were made into radio dramas for the program NBC University Theatre: "Noon Wine" in 1948, and both "Flowering Judas" and "Pale Horse, Pale Rider" in 1950. Porter herself appeared on the radio series, offering critical commentary on works by Rebecca West and Virginia Woolf. In the 1950s and 1960s, she occasionally appeared on television programs to discuss literature.

In 1962, Porter published her only novel, Ship of Fools. The novel was inspired by her recollections of a 1931 ocean cruise from Vera Cruz, Mexico, to Germany, and sharply depicted the political and religious reactions of its human characters. Its commercial success finally brought her financial security; she reportedly sold the film rights for 500.00 K USD. Producer David O. Selznick pursued the film rights, but United Artists, who owned the property, demanded 400.00 K USD. The novel was adapted for film by Abby Mann, with producer and director Stanley Kramer featuring Vivien Leigh in her final film performance.

Despite her earlier claim that she would win no more prizes after Ship of Fools, Porter received significant accolades in 1966. She was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the U.S. National Book Award for The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter. That same year, she was appointed to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her international recognition grew with five nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature between 1964 and 1968.

In 1966, Porter donated her literary papers to the University of Maryland. On her 78th birthday, the Katherine Anne Porter Room was opened at McKeldin Library (later moved to Hornbake Library) at the University of Maryland, housing many books from her personal library and other belongings. In 1977, she published The Never-Ending Wrong, a deeply personal account of the notorious trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, an event she had protested fifty years prior, reflecting her enduring commitment to social justice.

1.5. Later years and final works

In 1977, Katherine Anne Porter suffered a severe stroke. Following psychiatric evaluations, she was deemed incompetent, and her nephew, Paul Porter, was appointed as her guardian.

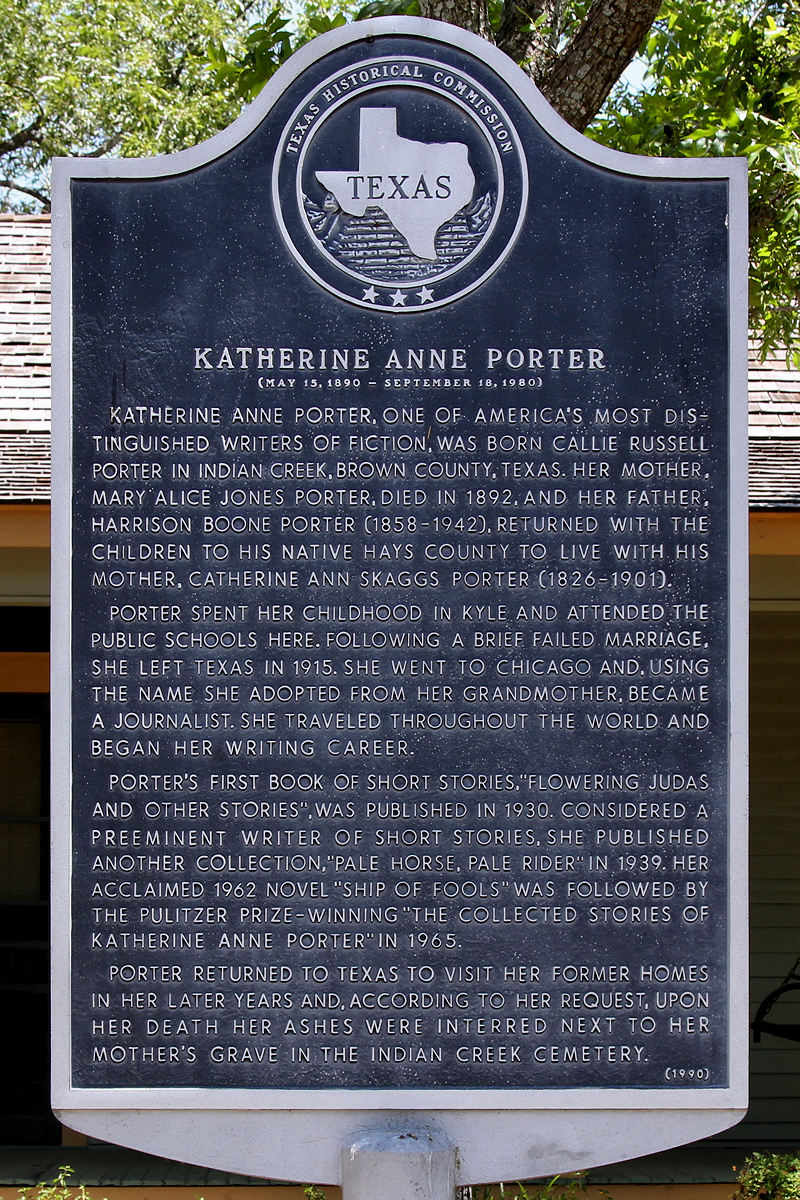

2. Death

Katherine Anne Porter died in Silver Spring, Maryland, on September 18, 1980, at the age of 90. Her ashes were interred next to her mother at Indian Creek Cemetery in Texas. In 1990, Recorded Texas Historic Landmark number 2905 was placed in Brown County, Texas, commemorating Porter's life and literary career.

3. Awards and honors

Katherine Anne Porter received numerous prestigious awards and honors throughout her career and posthumously, recognizing her significant contributions to literature:

- 1962 - Emerson-Thoreau Medal

- 1966 - Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Collected Stories (1965)

- 1966 - National Book Award for The Collected Stories (1965)

- 1967 - Gold Medal Award for Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Five nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature (1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968)

- 2006 - Featured on a United States postage stamp issued on May 15, 2006, with a value of 0.39 USD. She was the 22nd person honored in the Literary Arts commemorative stamp series.

4. Works

Katherine Anne Porter's literary output primarily consisted of short stories, though her single novel achieved widespread commercial success. Her non-fiction works provided valuable insights into her critical perspectives and personal reflections.

4.1. Short story collections

- Flowering Judas (Harcourt, Brace: 1930). This collection included eight of Porter's earliest short stories.

- Flowering Judas and Other Stories (Harcourt, Brace: 1935). An expanded edition that included the contents of the earlier collection along with four additional stories, earning her significant critical acclaim.

- Pale Horse, Pale Rider: Three Short Novels (Harcourt, Brace: 1939). This collection featured three stories Porter referred to as short novels: "Old Mortality", "Noon Wine" (which was adapted for American radio in 1948 and American television in 1966 and 1985), and "Pale Horse, Pale Rider" (adapted for American radio in 1950, Canadian television in 1963, and British television in 1964).

- The Leaning Tower and Other Stories (Harcourt, Brace: 1944). Comprised nine of Porter's short stories.

- The Old Order: Stories of the South (Harcourt, Brace: 1955). Included ten of Porter's previously published short stories, all set in the American South.

- The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter (Harcourt, Brace: 1964). This comprehensive volume gathered all twenty-six of Porter's previously published short stories, including the three she considered short novels, along with four new stories.

4.2. Novel

- Ship of Fools (Little, Brown, & Co.: 1962). This was Porter's only novel, which was later adapted into an American film in 1965.

4.3. Nonfiction

- The Days Before (Harcourt, Brace: 1952). This collection featured many of Porter's book reviews, critical essays, and memoirs.

- The Collected Essays and Occasional Writings of Katherine Anne Porter (Delacorte: 1970).

4.4. Posthumous publications

- Letters of Katherine Anne Porter (Atlantic Monthly Press: 1990), edited by Isabel Bayley. This volume included selections from over 250 letters Porter wrote to more than sixty correspondents between 1930 and 1966.

- "This Strange, Old World" and Other Book Reviews Written by Katherine Anne Porter (University of Georgia Press, 1991), edited by Darlene Harbour Unrue. This collection contained nearly 50 of the book reviews Porter had published in various periodicals throughout her lifetime.

- Uncollected Early Prose of Katherine Anne Porter (University of Texas Press: 1993), edited by Ruth M. Alvarez and Thomas F. Walsh. This work presented twenty-nine of Porter's prose pieces, both fiction and nonfiction, that had not been included in earlier published editions.

- Katherine Anne Porter's Poetry (University of South Carolina Press: 1996), edited by Darlene Harbour Unrue. This compilation gathered all thirty-two of the poems Porter had published in periodicals during her lifetime.

- Porter: Collected Stories and Other Writings (Library of America: 2008). This extensive edition included the complete text of The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter (Harcourt, Brace 1964) as well as many pieces from her two previous nonfiction collections.

- Selected Letters of Katherine Anne Porter: Chronicles of a Modern Woman (University Press of Mississippi: 2012), edited by Darlene Harbour Unrue. This collection featured over 130 complete letters Porter wrote to more than seventy correspondents between 1916 and 1979.

4.5. Other publications

- My Chinese Marriage by Mae Franking (Duffield & Co: 1921). This book was ghostwritten by Porter.

- Outline of Mexican Popular Arts and Crafts (Young & McCallister: 1922).

- Katherine Anne Porter's French Song Book (Harrison of Paris: 1933). This publication included seventeen French songs along with Porter's English translations.

- A Christmas Story (Delacorte: 1967). A previously published story by Porter about her niece, Mary Alice Hillendahl.

- The Never-Ending Wrong (Little, Brown, & Co.: 1977). Porter's reflections on the 1927 executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, an event she had protested decades earlier.

5. Influence and evaluation

Katherine Anne Porter's literary legacy is significant, marked by her distinctive prose style and her profound engagement with complex human experiences. Critically, she is highly regarded for her mastery of the short story form, earning her a place among the most celebrated American writers of the 20th century, often compared to William Faulkner for her contributions to Southern literature.

Her works frequently explored intricate social issues, human rights, and political themes, reflecting her own experiences and observations. Her early involvement with leftist movements in Mexico and her later disillusionment with them provided a nuanced perspective that informed her writing. A notable example of her commitment to social commentary is The Never-Ending Wrong, her reflection on the Sacco and Vanzetti case. In this work, she revisited the controversial trial and execution, which she had actively protested fifty years prior, demonstrating her enduring concern for justice and individual rights in the face of state power. This critical engagement with political and social injustices underscores her importance not only as a literary figure but also as a voice for human rights.