1. Life and Background

Karl Kraus's life journey from a wealthy Bohemian family to a prominent Viennese intellectual was marked by early academic explorations, a decisive break from conventional literary circles, and the founding of his influential independent publication.

1.1. Early Life and Education

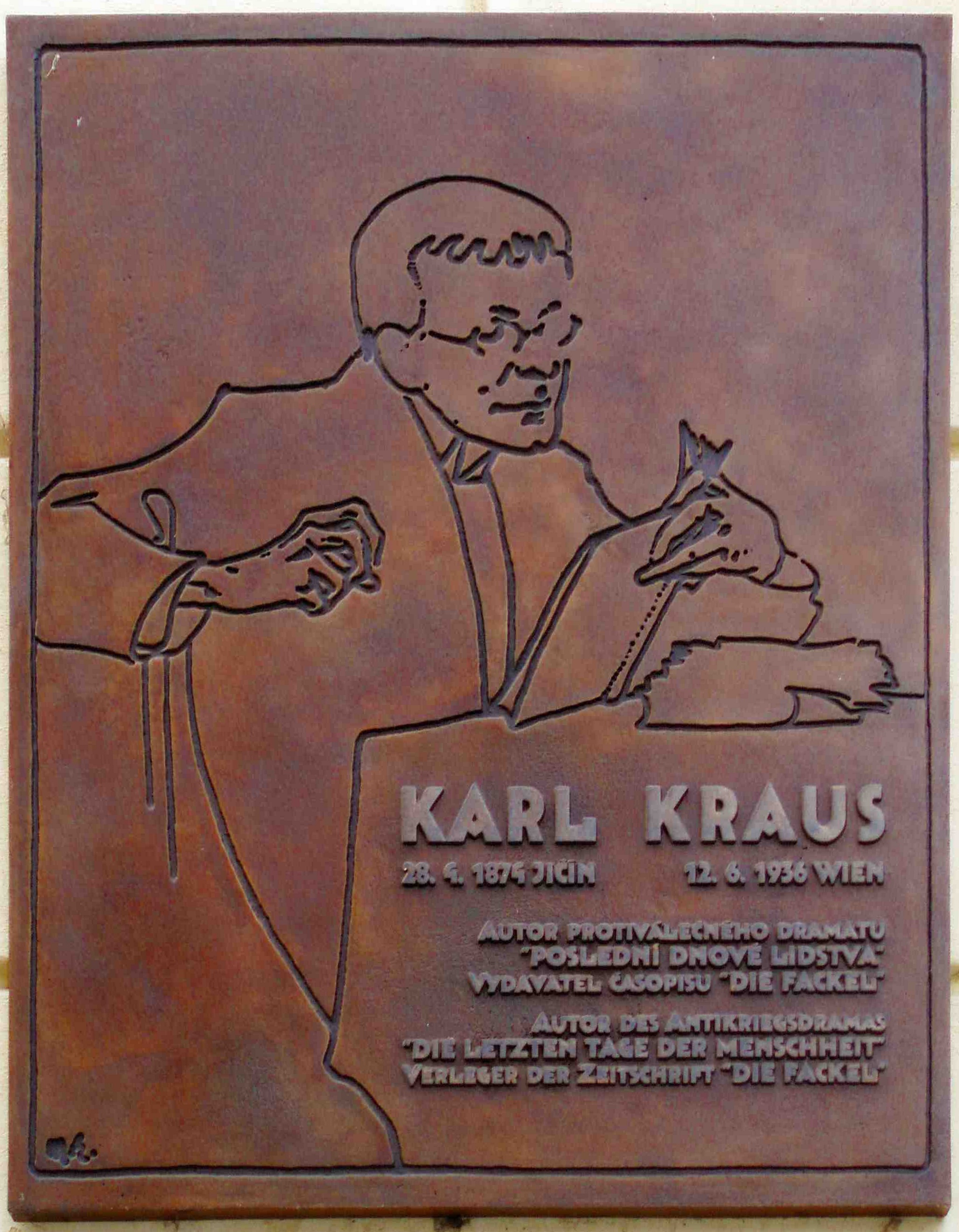

Kraus was born on 28 April 1874, into a prosperous Jewish family in Jičín, Kingdom of Bohemia, which was then part of Austria-Hungary and is now in the Czech Republic. His father, Jacob Kraus, was a papermaker, and his mother was Ernestine, née Kantor. In 1877, his family relocated to Vienna, the imperial capital, where he would spend most of his life. Tragically, his mother passed away in 1891 when Kraus was 17.

In 1892, Kraus enrolled at the University of Vienna as a law student. Around April of the same year, he began his journalistic contributions, starting with a critique of Gerhart Hauptmann's play The Weavers in the paper Wiener LiteraturzeitungGerman. During this period, he also made an unsuccessful attempt to pursue a career as an actor in a small theater. By 1894, he shifted his academic focus, changing his field of study to philosophy and German literature. He eventually discontinued his studies in 1896 without obtaining a diploma. It was around this time that he began his friendship with the writer Peter Altenberg.

1.2. Early Career and Founding of Die Fackel

After leaving university in 1896, Kraus ventured into the performing arts, taking on roles as an actor, stage director, and performer. He initially joined the literary circle known as the Young Vienna group, which included prominent figures such as Peter Altenberg, Leopold Andrian, Hermann Bahr, Richard Beer-Hofmann, Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Felix Salten. However, by 1897, Kraus sharply criticized and broke away from this group with his biting satire, Die demolierte LiteraturGerman (Demolished Literature). Following this, he was appointed as the Vienna correspondent for the Breslauer Zeitung newspaper, marking the start of his formal journalistic career.

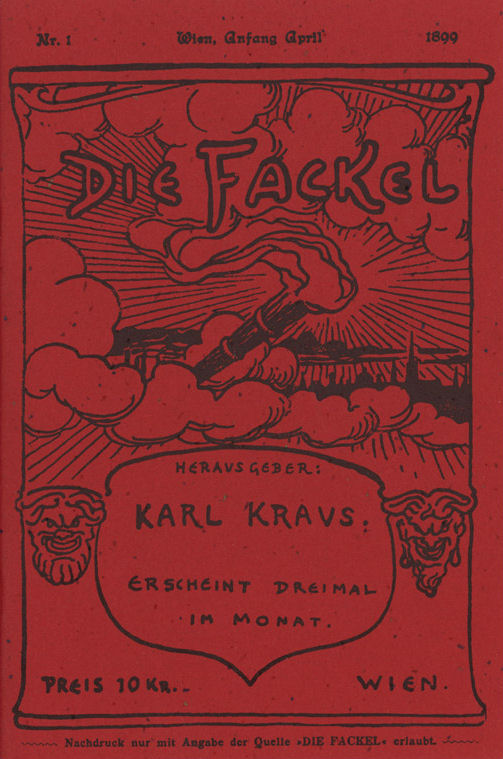

In 1898, as an uncompromising advocate for Jewish assimilation, Kraus launched a polemic attack against Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, in his work Eine Krone für ZionGerman (A Crown for Zion). The title of this work contained a wordplay: KroneGerman in German means both "crown" and the currency of Austria-Hungary from 1892 to 1918. One KroneGerman was the minimum donation required to participate in the Zionist Congress in Basel, and Herzl was often satirically referred to as the "king of Zion" (König von ZionGerman) by Viennese anti-Zionists. On 1 April 1899, Kraus formally renounced Judaism. In the same pivotal year, he founded his own magazine, Die Fackel (German: The Torch). He would continue to direct, publish, and primarily write for this magazine until his death in 1936, using it as a powerful platform to critique hypocrisy, psychoanalysis, the corruption within the Habsburg empire, the nationalism of the pan-German movement, laissez-faire economic policies, and a multitude of other societal issues.

2. Major Activities and Writings

Karl Kraus dedicated his life to journalistic and literary pursuits, with Die Fackel serving as his primary vehicle for delivering incisive social critique and publishing his extensive body of work, culminating in his monumental satirical drama, The Last Days of Mankind.

2.1. Satirical Journalism and Critical Stance

Kraus's primary activity revolved around satirical journalism, a genre he masterfully employed to deliver biting critiques of society, culture, and politics. He viewed the careless use of language as a symptom of deeper societal ailments, making linguistic precision a cornerstone of his critical approach.

2.1.1. Die Fackel Magazine

Die Fackel served as Kraus's main platform for his relentless attacks on societal ills. Initially, the magazine featured contributions from well-known writers and artists such as Peter Altenberg, Richard Dehmel, Egon Friedell, Oskar Kokoschka, Else Lasker-Schüler, Adolf Loos, Heinrich Mann, Arnold Schoenberg, August Strindberg, Georg Trakl, Frank Wedekind, and Franz Werfel, among others, during its first decade. However, after 1911, Kraus became almost the sole author of Die Fackel, writing nearly all its content himself. This gave the magazine an unparalleled editorial independence, largely due to Kraus's personal financial autonomy, allowing him to publish exactly what he desired. In total, 922 irregularly issued numbers of Die Fackel appeared throughout its run, and Kraus's work was published almost exclusively within its pages. Authors whom Kraus championed included Peter Altenberg, Else Lasker-Schüler, and Georg Trakl.

The magazine specifically targeted corruption, the sensationalist press, and brutish behavior prevalent in society. Notable adversaries and figures frequently criticized by Kraus in Die Fackel included Maximilian Harden, particularly in the context of the Harden-Eulenburg affair; Moriz Benedikt, the owner of the influential newspaper Neue Freie Presse; other journalists like Alfred Kerr and Hermann Bahr; and later, figures such as Imre Békessy and Johann Schober.

2.1.2. Early Controversies and Themes (1896-1909)

Kraus's early career with Die Fackel was marked by numerous legal battles. In 1901, he was sued by Hermann Bahr and Emmerich Bukovics, who felt personally attacked in the magazine. This set a precedent, and many more lawsuits from various offended parties followed in subsequent years, a testament to the provocative nature of his journalism. Also in 1901, Kraus discovered that his publisher, Moriz Frisch, had attempted to take over Die Fackel while he was away on a long journey, registering the magazine's front cover as a trademark and publishing a rival Neue Fackel (New Torch). Kraus successfully sued Frisch and won, after which Die Fackel was published by the printer Jahoda & Siegel, notably without a cover page.

In 1902, Kraus published Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität (Morality and Criminal Justice), a significant work that addressed one of his recurring preoccupations: the notion that sexual morality should be enforced through criminal justice. He famously stated, "The scandal starts when the police ends it," highlighting his critique of the hypocrisy and moral policing of his era. Beginning in 1906, Kraus started publishing his distinctive aphorisms in Die Fackel, which were later collected in his 1909 book, Sprüche und Widersprüche (Sayings and Gainsayings).

Kraus's influence extended to the arts as well. In 1904, he notably supported Frank Wedekind in staging his controversial play Pandora's Box in Vienna. This play, with its frank depiction of sexuality, violence, including lesbianism, and an encounter with Jack the Ripper, pushed against the boundaries of what was considered acceptable on stage at the time. While Wedekind's works are seen as precursors to Expressionism, Kraus later became a fierce critic of expressionist poets who, like Richard Dehmel, began producing war propaganda in 1914, demonstrating his unwavering commitment to truth over ideological alignment. In 1907, Kraus also attacked his former benefactor, Maximilian Harden, due to Harden's role in the infamous Harden-Eulenburg affair, one of his spectacular Erledigungen (Dispatches). A notable controversy arose with his 1911 text, Die Orgie, which exposed how the newspaper Neue Freie Presse was blatantly supporting Austria's Liberal Party's election campaign. Kraus orchestrated this as a "guerrilla prank," sending it as a fake letter to the newspaper, which Die Fackel later published. The enraged editor, having fallen for the trick, retaliated by suing Kraus for "disturbing the serious business of politicians and editors."

2.1.3. World War I and The Last Days of Mankind (1910-1919)

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914, and an obituary published in Die Fackel, the magazine ceased publication for several months. It reappeared in December 1914 with a significant essay titled "In dieser großen Zeit" ("In this grand time"). In this piece, Kraus declared his refusal to add his own words to the cacophony of a world consumed by war, stating: "In this grand time, which I used to know when it was this small; which will become small again if there is time; ... in this loud time that resounds from the ghastly symphony of deeds that spawn reports, and of reports that cause deeds: in this one, you may not expect a word of my own." In the subsequent years, Kraus consistently wrote against the First World War, facing repeated confiscations and obstructions of Die Fackel editions by censors.

Kraus's literary masterpiece is widely considered to be the monumental satirical play about World War I, Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind). He began writing this work in 1915 and first published it as a series of special Fackel issues in 1919. Its epilogue, "Die letzte Nacht" ("The last night"), had already appeared as a special issue in 1918. The play is an epic work that combines dialogue meticulously sourced from contemporary documents-such as newspaper articles, official communiqués, and personal letters-with apocalyptic fantasy and commentary delivered by two allegorical characters, "the Grumbler" and "the Optimist." Hans Eisler also composed music for the play.

Edward Timms described the work as a "faulted masterpiece" and a "fissured text." This assessment reflects the structural inconsistencies within the play, which arose from the evolution of Kraus's own political attitude during its composition, shifting from an aristocratic conservative viewpoint to a more democratic republican one. Despite its profound literary-historical significance and anti-war message, the play is notoriously long and complex, making it rarely performed in its complete form. In 1919, Kraus also published his collected war-related texts under the title Weltgericht (World Court of Justice). The following year, in 1920, he published the satire Literatur oder man wird doch da sehn (Literature, or You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet) as a direct response to Franz Werfel's play Spiegelmensch (Mirror Man), which had been an attack against Kraus himself.

2.1.4. Post-War Criticism and Political Engagement (1920-1936)

After the war, Kraus continued his significant critical activities. In January 1924, he initiated a notable dispute with Imre Békessy, the publisher of the tabloid Die Stunde (The Hour), accusing him of extorting money from restaurant owners by threatening them with negative reviews. Békessy retaliated with a libel campaign against Kraus, who, in turn, launched a powerful Erledigung against him, famously proclaiming, "Hinaus aus Wien mit dem Schuft!" ("Throw the scoundrel out of Vienna!"). As a result of Kraus's campaign, Békessy indeed fled Vienna in 1926 to avoid arrest.

A peak in Kraus's political commitment occurred in 1927 with his sensational attack on Johann Schober, the powerful Vienna police chief who had also served two terms as chancellor. This attack came after 89 rioters were shot dead by the police during the July Revolt of 1927. Kraus produced a poster that, in a single sentence, demanded Schober's resignation. This poster was widely displayed across Vienna and has since become an iconic image in 20th-century Austrian history, symbolizing public defiance against state violence.

In 1928, Kraus published the play Die Unüberwindlichen (The Insurmountables), which contained allusions to his battles against both Békessy and Schober. That same year, he also published the records of a lawsuit that Alfred Kerr had filed against him. Kerr, who had become a pacifist, sued Kraus after the latter published Kerr's earlier pro-war poems in Die Fackel, exposing his past enthusiasm for the conflict. In 1932, demonstrating his profound engagement with language and literature, Kraus translated Shakespeare's sonnets.

While Kraus had supported the Social Democratic Party of Austria from at least the early 1920s, his political stance underwent a controversial shift in 1934. Hoping that Engelbert Dollfuss could prevent Nazism from engulfing Austria, Kraus publicly supported Dollfuss's coup d'état, which established the Austrian fascist regime. This support significantly estranged Kraus from some of his long-time followers and admirers, marking a contentious point in his legacy.

In 1933, Kraus completed Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht (The Third Walpurgis Night), a scathing satire on Nazi ideology. Although initial fragments appeared in Die Fackel, Kraus deliberately withheld full publication of the work during his lifetime. His reasons included protecting friends and followers who were hostile to Adolf Hitler and still living in the Third Reich from Nazi reprisals. He also famously stated that "violence is no subject for polemic," suggesting the overwhelming nature of the Nazi regime defied traditional satire. The work famously begins with the sentence, Mir fällt zu Hitler nichts einGerman ("Hitler brings nothing to my mind"). Lengthy extracts from this work were published in a 315-page edition of Die Fackel titled "Warum die Fackel nicht erscheintGerman" ("Why Die Fackel is not published"), serving as Kraus's explanation for his relative public silence in the face of Hitler's rise to power. The very last issue of Die Fackel, number 922, was published in February 1936, shortly before his death.

2.2. Public Readings and Performances

Beyond his written work, Karl Kraus was renowned for his hundreds of highly influential public readings and one-man performances, which were a cornerstone of his career. Between 1892 and 1936, he gave approximately 700 such performances, captivating audiences with his unique interpretive style. Some of these public readings were recorded and remain accessible today.

The content of these readings was diverse, ranging from readings of dramas by prominent playwrights such as Bertolt Brecht, Gerhart Hauptmann, Johann Nestroy, Goethe, and Shakespeare. He also famously performed the operettas of Jacques Offenbach, accompanying himself on the piano and singing all the roles himself. These performances were not mere recitations but theatrical events that showcased Kraus's exceptional ability to embody the texts.

The impact of his public readings on the audience was significant. Many prominent intellectuals of the time, including Elias Canetti, regularly attended Kraus's lectures. Canetti was so deeply affected by these performances that he famously titled the second volume of his autobiography "Die Fackel" im Ohr ("The Torch" in the Ear), directly referencing Kraus's magazine and the immersive experience of his live readings. At the peak of his popularity, Kraus's lectures attracted an impressive four thousand people, underscoring his widespread appeal and the substantial influence he wielded over Viennese cultural life. His magazine, Die Fackel, also enjoyed significant circulation, selling forty thousand copies during this period.

3. Philosophy and Beliefs

Karl Kraus's philosophy was deeply rooted in his convictions about language, morality, and society, often manifested through his personal relationships and unique critical perspectives on contemporary movements like psychoanalysis.

3.1. Personal Relationships and Religious Affiliation

Kraus never married, but from 1913 until his death, he maintained a significant, albeit conflict-prone, relationship with Baroness Sidonie Nádherná von Borutín (1885-1950). Their connection was profound, and many of Kraus's works were written at Janowitz castle, which was the property of the Nádherný family. Sidonie Nádherná became an important confidante, a regular correspondent, and the dedicatee of many of his books and poems.

In 1911, Kraus was baptized into the Roman Catholic Church. However, he publicly left the Catholic Church in 1923. His disillusionment stemmed primarily from the Church's support for World War I. He famously, and sarcastically, claimed that his departure was motivated "primarily by antisemitism," specifically citing his indignation at the use of the Kollegienkirche in Salzburg as a venue for a theatrical performance by Max Reinhardt, which he saw as a desecration.

3.2. Views on Language and Society

A profound concern with language was central to Karl Kraus's entire outlook and critical methodology. He possessed a unique and deeply held conviction that the careless and imprecise use of language by his contemporaries was not merely a stylistic flaw but a critical symptom of their equally careless and insouciant treatment of the world itself. For Kraus, the degradation of language reflected a moral and intellectual decline in society.

This perspective is vividly illustrated by an anecdote recounted by the Austrian composer Ernst Krenek, who met Kraus in 1932. Krenek recalled Kraus saying something to the effect of: "I know that everything is futile when the house is burning. But I have to do this, as long as it is at all possible; for if those who were supposed to look after commas had always made sure they were in the right place, Shanghai would not be burning." This famous quote encapsulates Kraus's belief that attention to linguistic detail was fundamentally connected to broader societal well-being and justice, implying that the decay of language contributed to real-world catastrophes, such as the Japanese bombardment of Shanghai then occurring.

3.3. Criticism of Psychoanalysis

Karl Kraus was a notable and vocal critic of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis and the broader field of psychiatry. His critical views were extensively analyzed in two books by Thomas Szasz, Karl Kraus and the Soul Doctors and Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus's Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry, both of which portray Kraus as a harsh and uncompromising opponent of psychoanalytic theory.

However, other commentators, such as Edward Timms, have offered a more nuanced interpretation of Kraus's stance. Timms argued that while Kraus certainly had reservations about the application of some of Freud's theories, he did in fact respect Freud. According to Timms, Kraus's views were far less absolute and black-and-white than Szasz's portrayal suggests, indicating a more complex engagement with psychoanalysis rather than outright rejection.

4. Death

Karl Kraus's death in 1936 was preceded by a period of declining health. In February 1936, shortly after the publication of the final issue of Die Fackel (number 922), he was involved in a collision with a bicyclist. This incident led to him suffering from intense headaches and memory loss, significantly impacting his health. He gave his last public lecture in April 1936, marking the end of his prolific speaking career.

On 10 June 1936, Kraus suffered a severe heart attack while at the Café Imperial in Vienna. He died two days later, on 12 June 1936, in his apartment in Vienna. His funeral and burial took place at the Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) in Vienna.

5. Legacy and Assessment

Karl Kraus's life and prolific works have been the subject of extensive historical evaluation, encompassing a range of perspectives and controversies that continue to shape his enduring legacy.

5.1. Contemporary and Later Appraisals

Throughout his lifetime, Karl Kraus was a figure who consistently generated controversy, with strong opinions on both sides. Marcel Reich-Ranicki, a prominent literary critic, famously described him as 'vain, self-righteous and self-important'. Conversely, Kraus's dedicated followers revered him as an infallible authority, believing he would go to any length to support those he championed. Kraus himself considered posterity to be his ultimate audience, demonstrating this conviction by reprinting Die Fackel in volume form years after its initial publication, ensuring its continued access and relevance.

The Austrian author Stefan Zweig once referred to Kraus as "the master of venomous ridicule" (der Meister des giftigen SpottsGerman), encapsulating his sharp and often caustic satirical style. Giorgio Agamben, a contemporary philosopher, drew comparisons between Kraus and Guy Debord for their shared rigorous critique of journalists and media culture, highlighting Kraus's unique ability to expose "the facts that produce news and the news that are guilty of facts."

Gregor von Rezzori, another esteemed writer, lauded Kraus's life as "an example of moral uprightness and courage which should be put before anyone who writes, in no matter what language." Rezzori also spoke of witnessing Kraus's face "lit up by the pale fire of his fanatic love for the miracle of the German language and by his holy hatred for those who used it badly," emphasizing Kraus's profound linguistic passion and his disdain for linguistic sloppiness. The critic Frank Field quoted Bertolt Brecht's assessment of Kraus upon hearing of his death: "As the epoch raised its hand to end its own life, he was the hand," underscoring Kraus's perceived role as a critical consciousness of his time. Kraus's work has been widely described as the culmination of a distinct literary outlook, deeply rooted in Viennese fin-de-siècle culture.

5.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite widespread admiration, Kraus garnered numerous enemies due to the inflexibility and intensity of his partisanship. To these critics, he was often seen as a bitter misanthrope and a "poor would-be," a term used by Alfred Kerr. He was frequently accused of wallowing in hateful denunciations and his famed Erledigungen (breakings-off or settlements). Along with Karl Valentin, Kraus is considered a master of gallows humor, a dark and satirical form of comedy.

Until approximately 1930, Kraus primarily directed his satirical writings towards figures on the political center and left. He publicly stated that he considered the flaws of the political right to be too self-evident to warrant his extensive commentary. However, this focus shifted dramatically with the rise of Nazism, prompting his powerful anti-Nazi work, The Third Walpurgis Night.

One of the most significant controversies surrounding Kraus was his support for Engelbert Dollfuss's authoritarian coup d'état in 1934, which established the Austrian fascist regime. This decision, driven by Kraus's hope that Dollfuss could prevent Nazism from engulfing Austria, sharply alienated him from some of his most dedicated followers and left a contentious mark on his otherwise critically oriented legacy.

6. Selected Works

The following is a list of Karl Kraus's representative published works in their original German, followed by selected English and Japanese translations.

6.1. Original German Works

- Die demolierte Literatur (1897)

- Eine Krone für Zion (1898)

- Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität (1908)

- Sprüche und Widersprüche (1909)

- Die chinesische Mauer (1910)

- Pro domo et mundo (1912)

- Nestroy und die Nachwelt (1913)

- Worte in Versen (1916-1930)

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (1918)

- Weltgericht (1919)

- Nachts (1919)

- Literatur (1921)

- Untergang der Welt durch schwarze Magie (1922)

- Traumstück (1922)

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit: Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog (1922)

- Wolkenkuckucksheim (1923)

- Traumtheater (1924)

- Epigramme (1927)

- Die Unüberwindlichen (1928)

- Literatur und Lüge (1929)

- Shakespeares Sonette (1933)

- Die Sprache (posthumous, 1937)

- Die dritte Walpurgisnacht (posthumous, 1952)

6.2. Works in English Translation

- The Last Days of Mankind: A Tragedy in Five Acts (abridged) (1974), translated by Alexander Gode and Sue Allen Wright, F. Ungar Pub. Co., New York.

- No Compromise: Selected Writings of Karl Kraus (1977), edited by Frederick Ungar, including poetry, prose, and aphorisms from Die Fackel, correspondences, and excerpts from The Last Days of Mankind.

- In These Great Times: A Karl Kraus Reader (1984), edited by Harry Zohn, containing translated excerpts from Die Fackel, poems with original German alongside, and an abridged translation of The Last Days of Mankind.

- Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus' Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry (1990), by Thomas Szasz, includes Szasz's translations of several of Kraus's articles and aphorisms on psychiatry and psychoanalysis.

- Half Truths and One-and-a-Half Truths: selected aphorisms (1990), translated by Harry Zohn.

- Dicta and Contradicta (2001), translated by Jonathan McVity, a collection of aphorisms.

- The Kraus Project: Essays by Karl Kraus (2013), translated by Jonathan Franzen, with commentary and additional footnotes by Paul Reitter and Daniel Kehlmann.

- In These Great Times and Other Writings (2014), translated with notes by Patrick Healy (ebook only), a collection of eleven essays, aphorisms, and the prologue and first act of The Last Days of Mankind.

- The Last Days of Mankind (2015), complete text translated by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms, Yale University Press.

- The Last Days of Mankind (2016), alternate translation by Patrick Healy, November Editions.

- Third Walpurgis Night: the Complete Text (2020), translated by Fred Bridgham, Yale University Press.

6.3. Works in Japanese Translation

- Karl Kraus Works Collection (unfinished series)

- Karl Kraus Works Collection 5: Aphorisms (1978), edited and translated by Kibun Ikeuchi, Hosei University Press.

- Karl Kraus Works Collection 6: The Third Walpurgis Night (1976), translated by Yasuhiko Sato et al., Hosei University Press.

- Karl Kraus Works Collection 7・8: Language (1993), translated by Shoichi Takeda et al., Hosei University Press.

- Karl Kraus Works Collection 9: The Last Days of Mankind (Part 1) (1971), translated by Kibun Ikeuchi, Hosei University Press.

- Karl Kraus Works Collection 10: The Last Days of Mankind (Part 2) (1971), translated by Kibun Ikeuchi, Hosei University Press.

- Morality and Criminal Justice (1970), translated by Taro Komatsu, Hosei University Press.

- The End of the World Through Black Magic (2008), translated by Hiroyuki Yamaguchi and Eiji Kawano, Gendaishichosha.