1. Overview

Johann Georg Faust, also known as John Faustus, was a German alchemist, astrologer, and magician during the German Renaissance. Born around 1480 or 1466, and believed to have died around 1541, he was an itinerant scholar and performer, often accused by his contemporaries of being a con artist and a heretic. His life and activities quickly blurred with folk legend after his death, giving rise to the enduring Faust legend.

The Faust legend, which centers on a scholar who makes a pact with the devil in exchange for knowledge and worldly pleasures, gained widespread popularity through early chapbooks, notably the *Historia von D. Johann Fausten* published in 1587. This narrative served as a foundational text for numerous influential adaptations across literature, drama, and music. Key works include Christopher Marlowe's play *The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus* and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's monumental closet drama *Faust*. The character of Faust has become a powerful symbol in Western culture, representing the human pursuit of boundless knowledge, ambition, the moral implications of such a quest, and the inherent duality of good and evil within the human spirit.

2. Historical Faust

Establishing precise historical facts about Johann Georg Faust's life is challenging due to his early transformation into a figure of legend and literature. In the 17th century, some even doubted his historical existence, mistakenly identifying the legendary character with Johann Fust, an early German printer. However, Johann Georg Neumann's *Disquisitio historica de Fausto praestigiatore* in 1683 helped confirm Faust's historical presence through contemporary references.

2.1. Birth and Background

The exact details of Faust's birth remain uncertain. His birth year is commonly cited as either around 1480 or 1466. There is also ambiguity regarding his first name, with records referring to him as both Georg and Johann, and his place of origin, which is suggested to be either Knittlingen, Helmstadt near Heidelberg, or Stadtroda. Today, Knittlingen hosts an archive and a museum dedicated to Faust, though scholars Frank Baron and Leo Ruickbie advocate for Helmstadt as his birthplace.

Given records spanning over 30 years and the discrepancies in names and birthplaces, it has been proposed that there might have been two distinct itinerant magicians using the name "Faustus": one named Georg, active from approximately 1505 to 1515, and another named Johann, active in the 1530s. Records from the city archive of Ingolstadt include a letter dated June 27, 1528, mentioning a "Doctor Jörg Faustus von Haidlberg." Furthermore, archives of Heidelberg University show a "Georgius Helmstetter" enrolled from 1483 to 1487, earning a baccalaureus degree on July 12, 1484, and a magister artium on March 1, 1487. A record exists of a theology doctorate being awarded to a Johann Faust at Heidelberg University on January 15, 1509, though some suggest this could refer to a different individual.

2.2. Activities and Professions

Faust lived an itinerant life, traveling across various regions of southern Germany for over 30 years. He presented himself in multiple roles, including a physician, a doctor of philosophy, an alchemist, a magician, and an astrologer. He was known for performing magical tricks and casting horoscopes.

Notable instances of his activities include:

- In 1506, he appeared in Gelnhausen as a performer of magical tricks and horoscopes.

- In 1507, Johannes Trithemius, a German abbot and occultist, warned against a certain "Georgius Sabellicus," who styled himself "Georgius Sabellicus, Faustus junior, fons necromanticorum, astrologus, magus secundus" (Faustus the Younger, source of necromancers, astrologer, second magician). Trithemius alleged that Sabellicus blasphemously boasted of powers, even claiming he could replicate all the miracles of Christ. Trithemius also accused Sabellicus of abusing a teaching position in Sickingen by engaging in sodomy with his male students, escaping punishment through timely flight.

- In 1513, Conrad Mutianus Rufus recounted meeting a "chiromanticus" named "Georgius Faustus, Helmitheus Heidelbergensis" (likely meaning "demigod of Heidelberg") in an Erfurt inn, overhearing his vain and foolish boasts.

- On February 23, 1520, Faust was in Bamberg, where he performed a horoscope for the bishop and the town, receiving 10 Goldgulden for his services.

- In 1528, he visited Ingolstadt but was banished shortly thereafter.

- In 1532, he attempted to enter Nürnberg, but the junior mayor of the city issued an unflattering note to "deny free passage to the great nigromancer and sodomite Doctor Faustus."

- His last direct attestation dates to June 25, 1535, when his presence was recorded in Münster during the Anabaptist rebellion.

- In 1538, Faust was employed by Baron von Staufen.

Faust was frequently accused of fraud and was denounced by the church as a blasphemer in league with the devil. He was also rumored to have joined Protestantism.

2.3. Contemporary Records and Evaluations

Faust's contemporaries offered mixed evaluations of him. While often criticized, some also acknowledged his abilities.

Negative accounts include:

- Johannes Trithemius, in a letter dated August 20, 1507, described Faust as a "trickster and fraud."

- The junior mayor of Nürnberg in 1532 referred to him as a "great sodomite and nigromancer."

- Martin Luther reportedly criticized Faust, accusing him of using the devil's powers.

More positive assessments also exist:

- The Tübingen professor Joachim Camerarius recognized Faust as a respectable astrologer in 1536.

- Physician Philipp Begardi of Worms praised Faust's medical knowledge in 1539.

Other posthumous accounts further illustrate the perception of Faust:

- The theologian Johann Gast, in his *sermones conviviales* from 1548, mentioned a personal meeting with Faust in Basel. During this encounter, Faust reportedly provided the cook with an unusual kind of poultry. Gast also noted that Faust traveled with a dog and a horse, and rumors circulated that the dog could sometimes transform into a servant.

- Johannes Manlius, drawing on notes by Melanchthon in his *Locorum communium collectanea* (1562), stated that a "Johannes Faustus" was a personal acquaintance of Melanchthon's and had studied in Kraków. Manlius's account, however, already contains legendary elements, such as Faust boasting that the German emperor's victories in Italy were due to his magical intervention, and an alleged attempt by Faust to fly in Venice which resulted in him being thrown to the ground by the devil.

- Johannes Wier in *de prestigiis daemonum* (1568) recounted that Faustus was arrested in Batenburg for advising a local chaplain, Dorstenius, to use arsenic to remove his stubble. Dorstenius applied the poison to his face, losing not only his beard but also much of his skin. Wier claimed to have heard this anecdote directly from the victim.

- As late as 1602, Philipp Camerarius claimed to have heard tales of Faust directly from people who had met him in person. However, after the publication of the 1587 *Faustbuch*, it became increasingly difficult to distinguish historical anecdotes from rumor and legend.

The town of Bad Kreuznach has a "Faust Haus" restaurant, reportedly built in 1492, on the site of "the home of the legendary Magister Johann Georg Sabellicus Faust."

2.4. Death

Faust's death is generally dated to 1540 or 1541. He is widely believed to have died in an explosion during an alchemical experiment at the "Hotel zum Löwen" in Staufen im Breisgau. His body was reportedly found in a "grievously mutilated" state, with his blood and brains splattered on the walls and floors, and his eyes lying on the ground. This gruesome discovery was interpreted by his clerical and scholarly adversaries as a sign that the devil had personally come to collect his soul, fulfilling the terms of a supposed pact.

Johann Gast, in his 1548 account, stated that Faust had suffered a dreadful death and that his face would keep turning towards the earth even after his body was repeatedly turned onto its back. Accounts emphasize the violent and dismembered nature of his death, reinforcing the idea that it was a consequence of his dealings with dark forces.

3. Works Ascribed to Faust

Several grimoires and magical texts have been attributed to Faust, though their actual publication dates are often much later than the dates printed on their title pages. Many of these prints are artificially dated to his lifetime, such as "1540," "1501," "1510," or even earlier, like "1405" and "1469." In reality, these prints predominantly date to the late 16th century, around 1580, coinciding with the development of the *Volksbuch* (chapbook) tradition. Manuscript versions of the *Höllenzwang* text also exist from the late 16th century. Variants of the *Höllenzwang* attributed to Faust continued to be published for approximately two centuries, well into the 18th century. For example, a manuscript from around 1700 titled *Doctoris Johannis Fausti Morenstern practicirter Höllenzwang genant Der schwarze Mohr. Ann(o) MCCCCVII* (1407) contains text also found in the printed *Dr. Faustens sogenannter schwartzer Mohren-Stern, gedruckt zu London 1510*.

Some of the notable grimoires and magical works attributed to Faust include:

- Doctor Faustens dreyfacher Höllenzwang* (Rome, 1501)

- Geister-Commando* (*Tabellae Rabellinae Geister Commando id est Magiae Albae et Nigrae Citatio Generalis*) (Rome, 1501)

- D.Faustus vierfacher Höllen-Zwang* (Rome, 1501)

- Doctoris Johannis Fausti Cabalae Nigrae* (Passau, 1505)

- The black stair of Doctor John Faust* (London, 1510)

- Fausts dreifacher Höllenzwang* (*D.Faustus Magus Maximus Kundlingensis Original Dreyfacher Höllenzwang id est Die Ägyptische Schwarzkunst*) (1520), which describes Egyptian Nigromancy and magical seals for invoking seven spirits.

- Johannis Fausti Manual Höllenzwang* (Wittenberg, 1524)

- Praxis Magia Faustiana* (Passau, 1527)

- Fausti Höllenzwang oder Mirakul-Kunst und Wunder-Buch* (Wittenberg, 1540)

- Doctor Fausts großer und gewaltiger Höllenzwang* (Prague)

- Dr. Johann Faustens Miracul-Kunst- und Wunder-Buch oder der schwarze Rabe auch der Dreifache Höllenzwang genannt* (Lyon, 1669?)

- D. I. Fausti Schwartzer Rabe* (undated, 16th century)

- Doctor Faust's großer und gewaltiger Meergeist, worinn Lucifer und drey Meergeister um Schätze aus den Gewässern zu holen, beschworen werden* (Amsterdam, 1692)

These works were later compiled and edited in *Das Kloster* by J. Scheible (1849). Subsequent editions, such as the "Moonchild-Edition" by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Religions- und Weltanschauungsfragen in 1976 and 1977, and facsimiles by Poseidon Press and Fourier Verlag, have also been published.

4. Faust in Legend and Literature

The development of the Faust legend from its historical origins to its influential literary and artistic adaptations marks a significant trajectory in Western culture, tracing the evolution of a figure from a controversial individual to a universal symbol.

4.1. Chapbooks and the Formation of the Legend

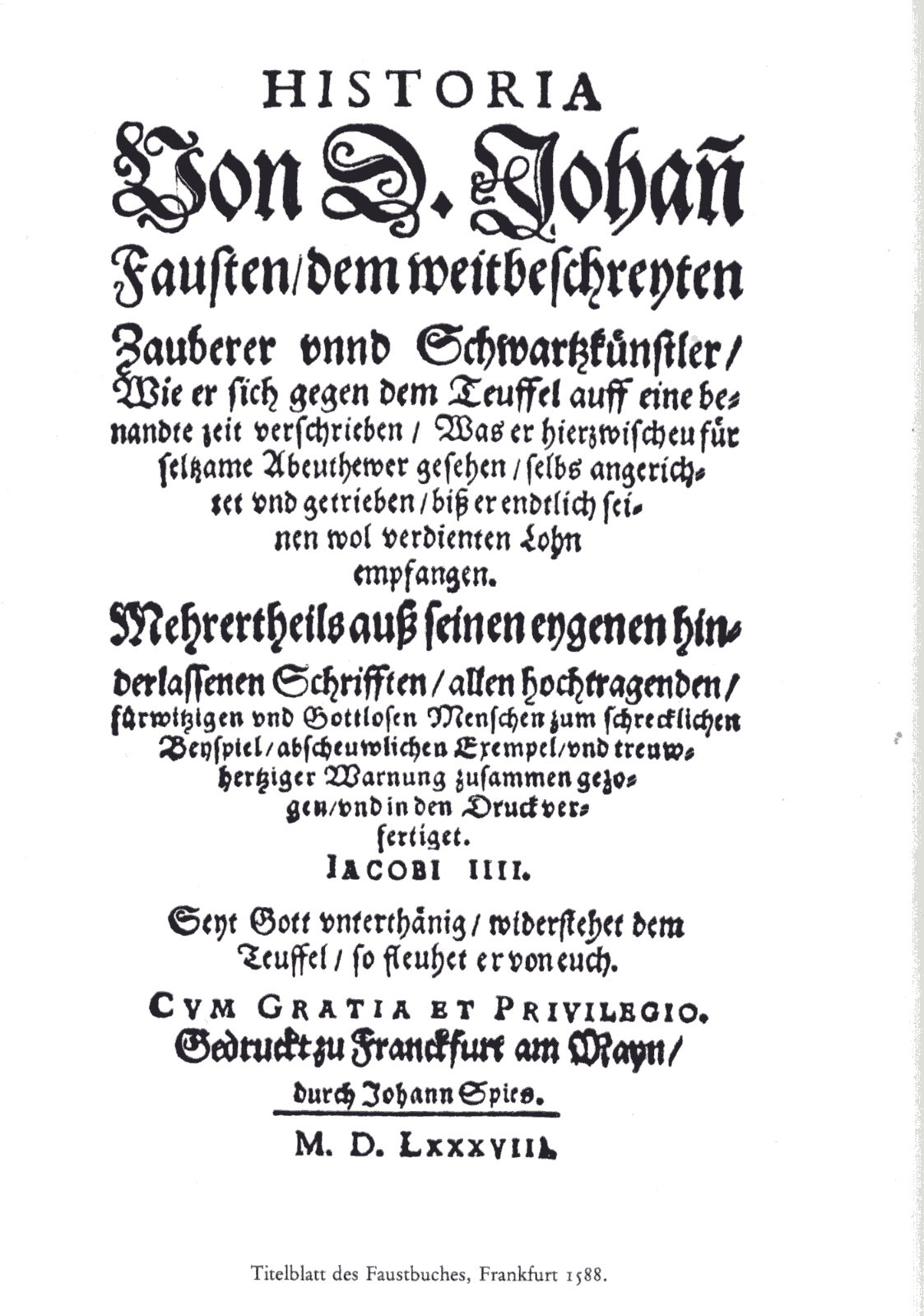

The crucial role in popularizing the Faust legend and shaping its narrative elements was played by early chapbooks, particularly the *Historia von D. Johann Fausten*, printed by Johann Spies in 1587. This German chapbook, which detailed Faust's alleged sins and magical exploits, became the foundational text for the literary tradition of the Faust character.

The *Historia* was swiftly translated into English in 1587, where it captured the attention of Christopher Marlowe. Marlowe's subsequent play, *The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus*, published around 1589, portrayed Faust as the archetypal adept of Renaissance magic. In the 17th century, Marlowe's work was re-introduced to Germany, often in the form of popular plays that gradually reduced Faust to a comical figure for public amusement.

Meanwhile, Spies's chapbook underwent further editions and excerpts by G. R. Widmann and Nikolaus Pfitzer. It was eventually re-published anonymously in a modernized form in the early 18th century as the *Faustbuch des Christlich Meynenden*. This edition became widely known and was notably read by Goethe in his youth.

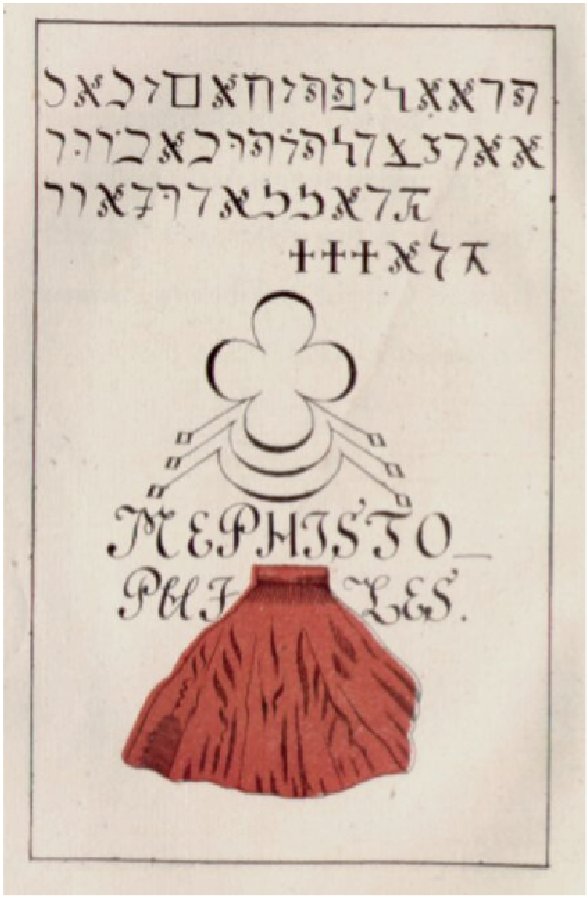

As summarized by Richard Stecher, this version recounts the story of a young man named Johann Faust, the son of a peasant, who studies theology in Wittenberg, alongside medicine, astrology, and "other magical arts." His insatiable desire for knowledge leads him to conjure the devil in a wood near Wittenberg. The devil appears in the guise of a Grey Friar, calling himself Mephistopheles. Faust enters into a pact with the devil, pledging his soul in exchange for 24 years of service. Mephistopheles provides Faust with a famulus named Christoph Wagner and a poodle named Prästigiar to accompany him on his adventures.

Faust then embarks on a life of pleasures and extraordinary feats. He is depicted riding out of Auerbachs Keller on a barrel in Leipzig and miraculously tapping wine from a table in Erfurt. His travels take him to the Pope in Rome, the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople, and the Holy Roman Emperor in Innsbruck. After 16 years, Faust begins to regret his pact and wishes to withdraw, but the devil persuades him to renew it, even conjuring Helen of Troy, with whom Faust fathers a son named Justus.

As the 24 years draw to a close, "Satan, chief of devils" appears to announce Faust's impending death. In a "last supper" scene in Rimlich, Faust bids farewell to his friends, admonishing them to repentance and piety. At midnight, a great noise erupts from Faust's room. The next morning, the room's walls and floors are found splattered with blood and brains, Faust's eyes lie on the floor, and his dead body is discovered in the courtyard. Some accounts suggest his son Justus killed him, while others state Mephisto tore him apart. Johannes Spies recorded 68 stories about Faust, portraying him as a "wandering devil-worker and sorcerer" who "allied with the devil" and was an "impious and a terrible example to warn everyone." These stories were filled with adventure and exploration of the secrets of heaven and earth.

4.2. Major Literary and Artistic Adaptations

The Faust legend has inspired a vast array of significant literary and artistic works, each contributing to its rich thematic and narrative developments.

- Christopher Marlowe's** *The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus* (1588-1592) is a seminal play that portrays Faust as the archetypical Renaissance magician, whose pursuit of forbidden knowledge leads to a tragic downfall.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's** *Faust* is arguably the most famous adaptation, a monumental closet drama published in two parts (Part One in 1808, Part Two completed in 1831). Goethe's *Faust* consists of 12,111 lines of poetry and prose, reflecting the author's evolving perspectives over decades. Part One, written in his youth, captures the spirit of rebellion against "German misery," characteristic of the *Sturm und Drang* movement. Part Two, completed shortly before his death at 82, shifts Faust's focus from earthly pleasures to a desire to contribute to humanity, culminating in the realization that "only those who daily conquer are worthy of freedom and life." Unlike the chapbook, Goethe allows Faust's soul to ascend to heaven, highlighting a more complex moral journey.

- Hector Berlioz's** musical composition *La damnation de Faust*, premiered in 1846, brought the legend to the operatic stage.

- Franz Liszt's** *Faust Symphony* of 1857 further cemented the legend's place in classical music.

Other notable treatments of the Faust legend from the 16th to 18th centuries include:

- Das Wagnerbuch* (1593, 1714)

- Das Widmann'sche Faustbuch* (1599)

- Dr. Fausts großer und gewaltiger Höllenzwang* (Frankfurt, 1609)

- Dr. Johannes Faust, Magia naturalis et innaturalis* (Passau, 1612)

- Das Pfitzer'sche Faustbuch* (1674)

- Dr. Fausts großer und gewaltiger Meergeist* (Amsterdam, 1692)

- Faustbuch des Christlich Meynenden* (1725)

Later literary and artistic works include:

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (fragment)

- Carl Joseph Simrock: *Puppenspiel Faust* (1846), a puppet play based on older traditions, some dating back to 1746.

- Friedrich Maximilian Klinger (1791)

- Nikolaus Lenau (1836)

- Heinrich Heine: a ballet libretto (1851)

- Thomas Mann: *Doktor Faustus* (1947), a novel exploring the Faustian theme in the context of 20th-century German history.

- Paul Valéry: *Mon Faust* (1946)

The legend has also been adapted into numerous operas, ballets, films, and other forms of media, demonstrating its pervasive influence across various artistic disciplines.

4.3. Faust Myth and Symbolism

The Faust figure embodies enduring themes and symbolic meanings that resonate deeply within human experience, reflecting the complexities of ambition, morality, and the pursuit of knowledge. Central to the myth is the concept of the deal with the Devil, where Faust trades his soul for forbidden knowledge, magical powers, and worldly pleasures. This pact symbolizes the human desire to transcend limitations and acquire ultimate understanding or control, often at a profound moral cost.

The pursuit of knowledge is a primary theme. Faust's insatiable intellectual curiosity drives him to seek answers beyond conventional academic and theological boundaries, leading him to magic and the supernatural. This represents the human quest for enlightenment and mastery over the natural world, but also highlights the potential dangers of unchecked ambition and intellectual arrogance.

The Faust legend also explores the duality of good and evil within the human spirit. Goethe's *Faust*, in particular, delves into this theme, with Faust expressing the internal conflict of "two souls" residing within him: one driven by passionate earthly desires, and the other striving for purity and transcendence. This internal struggle between base instincts and noble aspirations is a core aspect of the human condition. The idea that "the existence of Faust and Mephisto within each person is real" suggests that the conflict between temptation and will is a universal struggle.

Faust's ultimate fate, whether damnation as in the chapbooks or salvation as in Goethe's version, reflects differing interpretations of human agency, redemption, and the moral implications of one's choices. In the chapbooks, Faust's gruesome death serves as a dire warning against blasphemy and alliance with evil. In contrast, Goethe's Faust, through continuous striving and action, ultimately achieves salvation, suggesting that persistent effort and a desire to contribute to humanity can lead to redemption, even after making grave errors. This transformation from a figure of damnation to one of potential salvation highlights the evolving philosophical and theological perspectives on human nature and destiny. Faust, thus, becomes a unique figure in world literature, daring to exchange his soul for creative power and discovery, embodying a struggle between good and evil, life and death, temptation and will.

5. Influence and Legacy

The figure of Faust and his legend have left an indelible mark on global culture, inspiring countless artistic creations and sparking ongoing debates across various disciplines.

5.1. Positive Reception and Artistic Inspiration

Faust's enduring appeal as a source of artistic inspiration stems from his representation of the quintessential human quest for knowledge, experience, and self-transcendence. He symbolizes the boundless ambition of humanity, willing to challenge conventional boundaries and even sacrilege to unlock the secrets of the universe. This drive to explore beyond the known, to gain mastery over nature and destiny, has resonated with artists, writers, and thinkers across centuries.

Goethe's *Faust*, in particular, elevated the legend to a profound philosophical and literary masterpiece, shaping the modern understanding of the character. This work, with its exploration of human striving and redemption, has itself become a cornerstone of Western literature, inspiring subsequent generations to grapple with similar themes of ambition, morality, and the human condition. Through his pact with Mephistopheles, Faust gains the ability to ascend to heaven, descend to hell, rejuvenate, and reclaim land, symbolizing the immense creative and conquering power of humanity. He becomes a figure who explores the "secrets of heaven and earth," representing a "sacred transgression" that ultimately leads to a deeper understanding of existence.

5.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his inspirational qualities, Faust has also been a subject of significant criticism and controversy. Historically, the real Johann Georg Faust was frequently accused of being a con artist, a blasphemer, and a practitioner of forbidden arts, including sodomy. These contemporary condemnations underscore the societal anxieties of the time regarding magic, heresy, and moral transgression. The Nürnberg mayor's note to "deny free passage to the great nigromancer and sodomite Doctor Faustus" exemplifies the severe disapproval he faced.

The moral implications of the Faust legend itself have been a continuous subject of debate. The central theme of a deal with the Devil raises fundamental questions about the price of knowledge, the corrupting influence of power, and the ethical boundaries of human ambition. The chapbooks, such as the *Historia von D. Johann Fausten*, explicitly presented Faust as an "impious and a terrible example to warn everyone," emphasizing the catastrophic consequences of his pact. His gruesome death, interpreted as the devil claiming his soul, served as a stark cautionary tale against straying from religious and moral norms.

The symbolic representation of Faust also reflects societal anxieties about the pursuit of knowledge without ethical restraint. The legend warns against the dangers of unchecked intellectual curiosity and the potential for human ambition to lead to self-destruction. Even in Goethe's more redemptive portrayal, the internal conflict between Faust's noble aspirations and his base desires highlights the perpetual struggle within humanity. The notion that "the existence of Faust and Mephisto within each person is real" underscores the ongoing debate about the balance between good and evil, temptation and will, that defines the human experience.