1. Overview

Joan II of Navarre (JeanneFrench; Juana II de NavarraSpanish; Joana II.a NafarroakoaBasque; January 28, 1312 - October 6, 1349) was the ruling Queen of Navarre from 1328 until her death. As the only surviving child of Louis X (Louis I of Navarre) and his first wife, Margaret of Burgundy, Joan's early life was marked by significant controversy and a prolonged struggle for her right to inherit. Despite the fact that Navarre's succession laws permitted female monarchs, her legitimacy was questioned due to the Tour de Nesle Affair involving her mother, and she was disinherited from the French throne by the application of the Salic law, which excluded women.

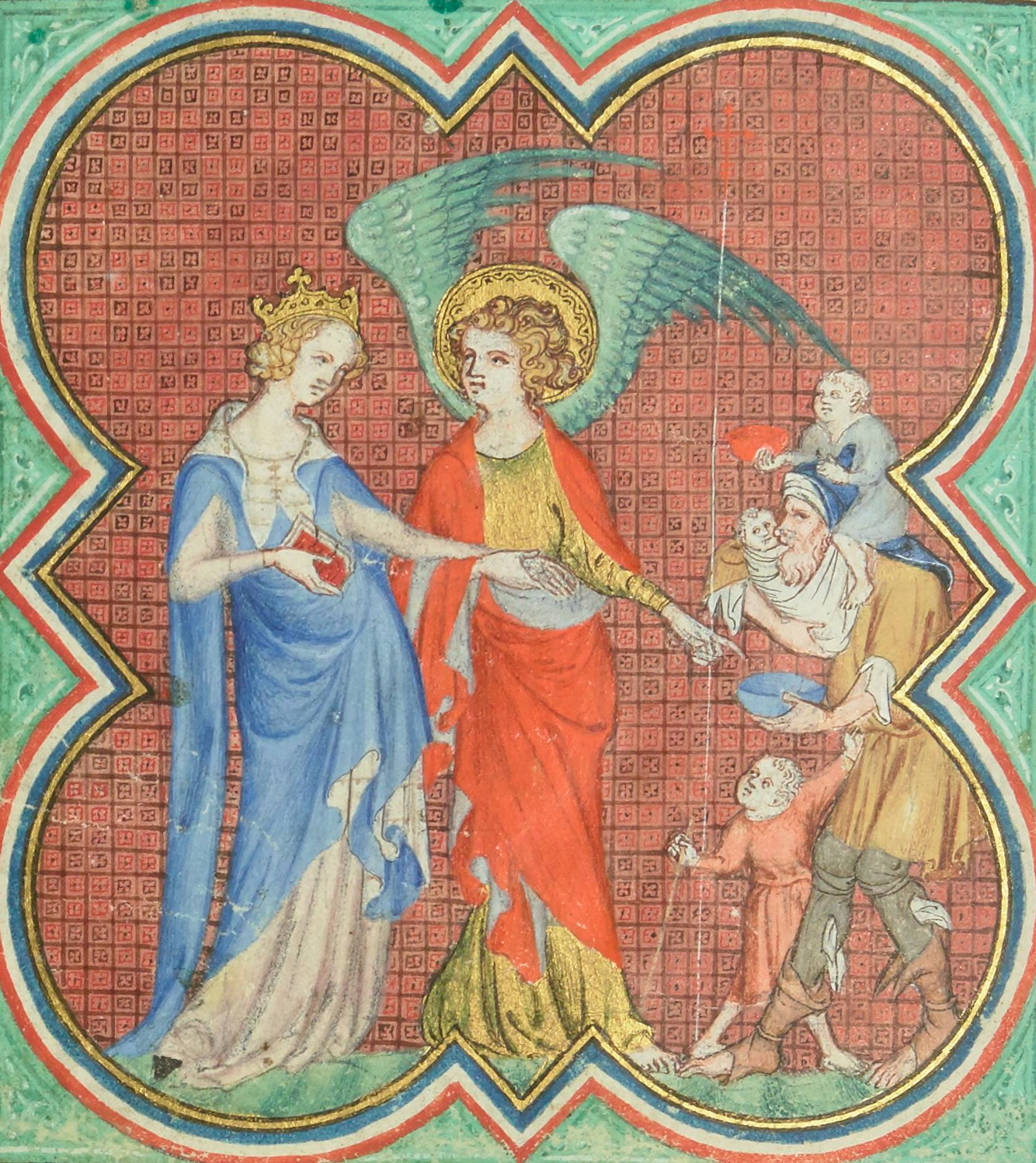

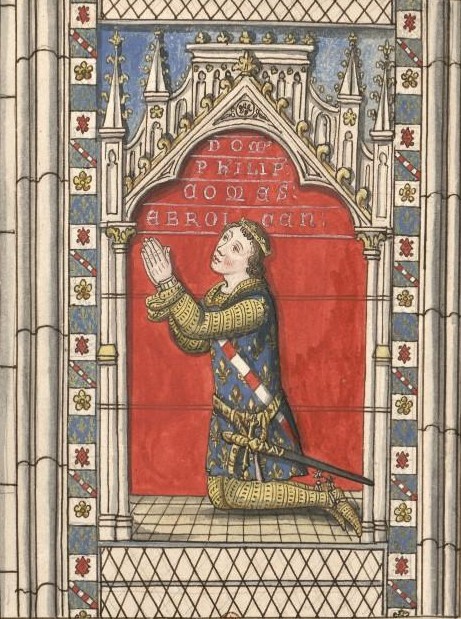

However, following the extinction of the direct male line of the Capetian dynasty in France, the Navarrese Estates declared Joan their rightful monarch. She ascended the throne alongside her husband, Philip of Évreux, ruling jointly until his death in 1343, and then as sole monarch. Her reign was characterized by cooperative governance, efforts to maintain peace with neighboring states, and significant domestic administrative measures, including legal reforms, infrastructure projects such as irrigation systems, and notable actions taken against anti-Jewish pogroms. Joan's reign demonstrated the capability of a female monarch in a period of political turmoil, ensuring the stability and autonomy of Navarre, even as she pragmatically navigated broader European conflicts like the early stages of the Hundred Years' War.

2. Early Life and Contested Succession

Joan's birth and early years were overshadowed by a significant royal scandal and complex succession issues that would profoundly impact her future, particularly regarding her claim to the French and Navarrese thrones.

2.1. Birth and Uncertain Legitimacy

Joan was born on January 28, 1312, as the daughter of Louis I of Navarre (who later became Louis X of France) and his first wife, Margaret of Burgundy. Her father was the eldest son and heir of King Philip IV of France and Joan I of Navarre. However, Joan's legitimacy became dubious due to the Tour de Nesle Affair in 1314, which involved her mother, Margaret, and Margaret's sisters-in-law, Joan and Blanche of Burgundy. Margaret and Blanche were accused of adultery with two knights, the Aunay brothers. After torture, one of the brothers confessed to having been Margaret and Blanche's lovers for three years. The Aunay brothers were executed, and Margaret and Blanche were imprisoned. Margaret died in prison at Château Gaillard, possibly due to natural causes exacerbated by harsh treatment, or potentially by Louis's order. This scandal created a lasting stain on Joan's reputation, casting doubt on her paternity, as the affair coincided with the year of her birth. Despite this, on his deathbed in 1316, Louis X explicitly declared Joan his legitimate daughter.

2.2. French Succession Crisis and Disinheritance

Upon the death of Joan's paternal grandfather, Philip IV, on November 26, 1314, her father ascended the French throne as Louis X. Louis X died prematurely on June 5, 1316, leaving his second wife, Clementia of Hungary, pregnant. An agreement among powerful French lords, completed on July 16, stipulated that if Clementia bore a son, he would be crowned King of France. If she bore a daughter, that daughter, along with Joan, could only inherit the Kingdom of Navarre and the counties of Champagne and Brie, which Louis X had inherited from his mother, Joan I of Navarre. It was also agreed that Joan would be sent to her mother's relatives in Burgundy, and her marriage would require the consent of the French royal family.

Clementia gave birth to a son, John the Posthumous, on November 13, 1316, but he died five days later. This triggered a severe succession crisis. Joan's maternal uncle, Odo IV, Duke of Burgundy, attempted to negotiate with Philip the Tall, Louis X's brother and Joan's paternal uncle, to protect Joan's interests. However, Philip instead arranged his own coronation, which took place in Reims on January 9, 1317. The Estates-General of 1317, an assembly of French lords, further solidified Philip V's position on February 2 by declaring that a woman could not inherit the French crown, reinforcing the concept of Salic law. Most Navarrese noblemen initially swore fidelity to Philip V, who also refused to grant Champagne and Brie to Joan. Joan's maternal grandmother, Agnes of France, Duchess of Burgundy, protested Philip V's coronation through letters to leading French lords, arguing that Joan's disinheritance violated "divine right of law, by custom, in the usage kept in similar cases in empires, kingdoms, fiefs, in baronies in such a length of time that there is no memory of the contrary." Despite these protests, Philip V faced little opposition and his uncle, Charles of Valois, defeated Joan's supporters.

2.3. Marriage to Philip of Évreux and Early Life in France

On March 27, 1318, an agreement was concluded between Philip V and Odo IV. Philip V married his eldest daughter, Joan, to Odo IV, recognizing them as heirs to the counties of Burgundy and Artois. In return, Joan was to marry her cousin, Philip of Évreux, receiving a dowry of 15,000 livres tournois in rents and the right to inherit Champagne and Brie if Philip V died without sons. It was also agreed that Joan would renounce her claims to France and Navarre upon turning twelve, though there is no evidence this renunciation ever formally took place.

Joan and Philip's marriage was celebrated on June 18, 1318, when Joan was only six years old and Philip twelve. After her marriage, Joan lived with Philip's grandmother, Marie of Brabant. Although they lived near each other, Philip and Joan were not raised together due to their age difference. Their marriage was only consummated in 1324. Philip of Évreux was the grandson of Philip III of France and inherited the county of Évreux. This gave the couple extensive landholdings in northern France, including Normandy and Champagne.

5. Later Life and Death

Joan's later years were marked by the growing shadow of the Hundred Years' War and ultimately, the devastating Black Death.

5.1. Role in the Hundred Years' War

Joan had intended to visit Navarre again after Philip III's death, but she never returned. This was most likely due to the escalating threat of invasion to her family's domains in France during the early stages of the Hundred Years' War. Initially, Joan and Philip had supported King Philip VI of France against Edward III of England, who asserted his claim to the French throne as the son of Joan's aunt, Isabella of France.

However, by 1346, Joan grew increasingly disillusioned with Philip VI's perceived failures as a military leader. Demonstrating her pragmatic approach to protecting her territories, she boldly concluded a truce with the Earl of Lancaster in November of that year. This agreement granted Edward III's troops free passage through her county of Angoulême in exchange for protection of her lands. She also committed not to construct new fortifications or permit Philip VI's army to use the existing ones within her domains. Philip VI was in no position to take action against her for this independent diplomatic move, highlighting Joan's ability to prioritize the security and stability of her realm amidst the larger conflict.

5.2. Death and Burial

Joan II of Navarre succumbed to the devastating Black Death on October 6, 1349. She was 37 years old at the time of her death, which occurred at Château de Conflans. In her last will, she made a specific request that her son, Charles II, finance the construction or renovation of a chapel in Santa Maria of Olite.

Joan's body was interred in the Basilica of St Denis, the traditional burial place for French monarchs. However, her heart was buried separately alongside her husband's heart at the now-demolished church of the Couvent des Jacobins in Paris. This practice of separate heart burial was common among royalty during the period, symbolizing a special spiritual or personal connection to a particular place or individual.

6. Family and Descendants

Joan II's marriage to Philip of Évreux was politically strategic and productive, leading to the birth of nine children who would play significant roles in the complex tapestry of European royal families.

6.1. Children

Joan married Philip of Évreux on June 18, 1318. They had nine children together:

- Joan (c. 1326-1387): She was initially considered as a bride for the future Peter IV of Aragon but ultimately became a nun at the Franciscan convent at Longchamp.

- Maria (c. 1329-1347): She became the first wife of Peter IV of Aragon, fulfilling the earlier alliance negotiations.

- Louis (1330-1334): Died in childhood.

- Blanche (1331-1398): Became the second wife of Philip VI of France, marrying him after her mother's death.

- Charles (1332-1387): He succeeded his parents as Count of Évreux and King of Navarre, known as Charles the Bad.

- Philip (c. 1333-1363): He was Count of Longueville and married Yolande de Dampierre.

- Agnes (1334-1396): Married Gaston III, Count of Foix.

- Louis (1341-1372): Count of Beaumont-le-Roger, he first married Maria de Lizarazu and then Joanna, Duchess of Durazzo.

- Joan (after 1342-1403): Married John I, Viscount of Rohan.

6.2. Family Tree

Joan II of Navarre's lineage connects her deeply to both the Capetian dynasty of France and the House of Burgundy. Her father, Louis X of France, was the son of Philip IV of France and Joan I of Navarre. Her mother, Margaret of Burgundy, was the daughter of Robert II of Burgundy and Agnes of France. Through her father, Joan descended from the main Capetian line that had ruled France and Navarre, while her mother connected her to a powerful ducal house. Her husband, Philip III of Navarre, was a grandson of Philip III of France through his son Louis of Évreux, making him a cousin to Joan's father. This marriage further intertwined the Navarrese monarchy with branches of the French royal family, which would be crucial for future successions and alliances within Europe.