1. Early Life and Background

Joachim du Bellay's early life was marked by noble lineage and personal hardship, which influenced his later literary pursuits and his deeply reflective poetry.

1.1. Birth and Family

Joachim du Bellay was born around 1522 at the Château de la Turmelière in Liré, near Angers, in the historical region of Anjou, France. He was the son of Jean du Bellay, Lord of Gonnord, and Renée Chabot, who was the heiress of La Turmelière. His family was an old noble lineage, having produced notable figures such as Cardinal Jean du Bellay and Guillaume du Bellay, both his first cousins. Du Bellay's childhood was challenging as both his parents died when he was young, leaving him under the guardianship of his elder brother, René du Bellay. René reportedly neglected Joachim's education, allowing him to grow up largely unsupervised at La Turmelière. This period of solitude in the forests and by the banks of the Loire River fostered a contemplative and melancholic disposition in the young du Bellay.

1.2. Education and Early Influences

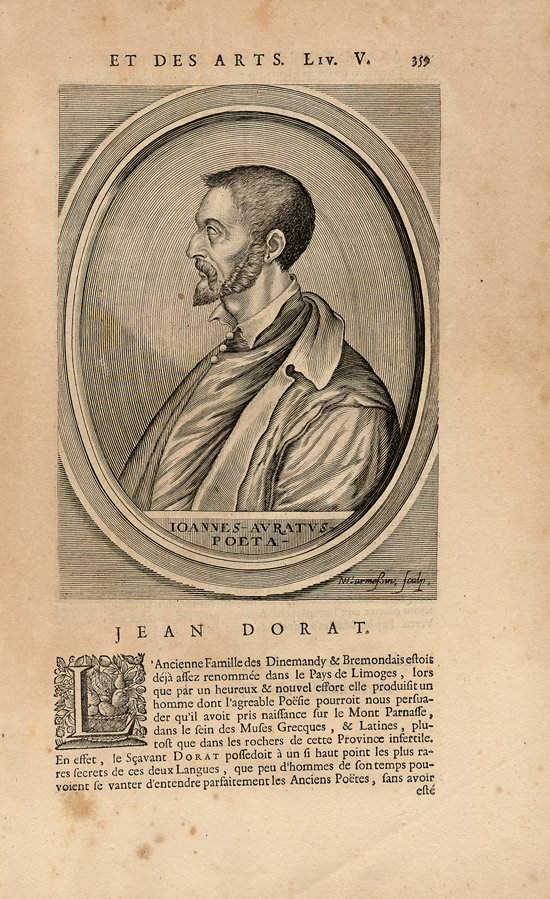

Despite his initial neglected education, at the age of twenty-three, du Bellay received permission to study law at the University of Poitiers. This pursuit was likely intended to secure him a position through his influential kinsman, Cardinal Jean du Bellay. During his time at Poitiers, he was exposed to the burgeoning intellectual movement of Humanism. He encountered several significant figures who would shape his early literary and intellectual development, including the humanist scholar Marc Antoine Muret and the Latin poet Jean Salmon Macrin (1490-1557). He also likely met Jacques Peletier du Mans, who had already published a translation of Horace's Ars Poetica with a preface that outlined many ideas later championed by La Pléiade. Furthermore, he studied under Jean Dorat, a distinguished Hellenist scholar, who taught him about ancient Greek and Latin writers and Italian poets.

2. Literary Career and La Pléiade

Du Bellay's literary career truly began with his pivotal meeting with Pierre de Ronsard and their subsequent formation of La Pléiade, a group dedicated to revolutionizing French literature.

2.1. Meeting Pierre de Ronsard

A decisive moment in du Bellay's life occurred around 1547 when he met Pierre de Ronsard. Accounts suggest this meeting took place either at an inn on the way to Poitiers or while they were students at the University of Poitiers. Both men were in their twenties and shared common relatives, friends, and a mutual ambition to pursue poetry. They had both initially dreamed of military careers but were thwarted, in du Bellay's case, by early-onset deafness. Ronsard, already writing poetry and aspiring to become a great poet, persuaded du Bellay to join him in Paris to study ancient writers at the Collège de Coqueret. Their shared literary aspirations quickly forged a close and enduring friendship, marking the true beginning of the French school of Renaissance poetry.

2.2. Formation and Aims of La Pléiade

Under the guidance of their esteemed Greek scholar, Jean Dorat, at the Collège de Coqueret, du Bellay and Ronsard, along with other friends like Jean-Antoine de Baïf, formed a literary circle. This group, initially known as the "Brigade" (Brigade), was formally established as La Pléiade around 1553. While Ronsard and Baïf were particularly influenced by Greek models, du Bellay leaned more towards Latin, a preference that perhaps contributed to the more national and familiar tone of his poetry.

The Pléiade's collective goal was to reform and enrich French poetry and language. They aimed to elevate French to the status of classical languages like Greek and Latin, making it a suitable vehicle for high art and intellectual discourse. Their program involved defending the French language against those who preferred Latin for serious works, cultivating new poetic genres, enriching the French vocabulary through internal development and judicious borrowing from Italian, Latin, and Greek, and defining new poetic disciplines. They advocated for imitation of classical forms over mere translation and stressed the importance of a distinct poetic language and style.

3. Major Works and Literary Contributions

Joachim du Bellay's literary output significantly shaped the course of French literature, particularly through his theoretical manifesto and his innovative poetry collections.

3.1. Défense et illustration de la langue française

In 1549, the Pléiade group decided to publish a manifesto, which was entrusted to du Bellay for redaction, despite Ronsard being the chosen leader of the group. This seminal work, Défense et illustration de la langue française (Defense and Illustration of the French Language), served as the group's declaration of principles and was both a complement to and a refutation of Thomas Sébillet's Art poétique, published in 1548. Sébillet had articulated many ideas shared by the Pléiade but held up Clément Marot and his disciples as models, a point of strong disagreement for Ronsard and his friends.

Du Bellay's Défense argued that the French language, though then considered too "poor" for higher forms of poetry, could be cultivated to rival classical tongues. He condemned those who despaired of their mother tongue and used Latin for their more ambitious works. The manifesto advocated for "imitation" of classical authors rather than simple translation, though it did not precisely detail the method. It proposed developing a distinct poetic language and style, separate from prose, and enriching French through its internal resources and careful borrowings from Italian, Latin, and Greek. Both du Bellay and Ronsard emphasized prudence in these borrowings, rejecting accusations of wanting to Latinize French. The work was a spirited defense of poetry and the potential of the French language, effectively declaring war on writers with less ambitious views. It also bolstered French political debate as a means for learned men to reform their country. The Défense faced immediate criticism from various writers like Sébillet, Guillaume des Autels, and Barthélemy Aneau, who pointed out inconsistencies in its arguments, such as depreciating native poets while defending the French language. Du Bellay responded to his assailants in the preface to the second edition of Olive (1550) and through polemical poems.

3.2. Poetry Collections

Du Bellay's poetic output encompassed several significant collections, each contributing uniquely to the development of French poetry.

3.2.1. Olive

First published in 1549, Olive is a collection of fifty sonnets, later expanded to 115 in its second edition (1550). This collection is largely modeled after the poetry of Petrarch, Ariosto, and other contemporary Italian poets. While the title Olive has been speculated to be an anagram for a "Mlle Viole," the poems generally lack strong personal passion, suggesting they might have been a Petrarchan exercise. This is further supported by the dedication to his lady being replaced by one to Marguerite de Valois, sister of Henry II, in the second edition. Although du Bellay did not introduce the sonnet form to French poetry, he was instrumental in acclimatizing it, making it a widely adopted and popular poetic structure. He later even satirized the excesses of sonneteering when it became a widespread mania.

3.2.2. Antiquités de Rome

Composed during his time in Rome and published in 1558, Antiquités de Rome is a sequence of forty-seven sonnets that reflect du Bellay's observations and meditations on the ruins of classical Rome. These sonnets are more personal and less imitative than those in Olive, striking a melancholic and reflective tone. Themes include the transience of human glory, the decay of ancient civilizations, and the poet's personal sense of disillusionment with the contemporary state of Rome compared to its glorious past. Sonnet III, "Nouveau venu qui cherches Rome en Rome," notably reflects the influence of a Latin poem by Jean or Janis Vitalis. This collection profoundly influenced later poets, including Edmund Spenser, who translated it into English as The Ruins of Rome (1591), and Francisco de Quevedo, who rendered a sonnet into Spanish. The themes explored in Antiquités were later revived in French literature by writers like Volney and François-René de Chateaubriand.

3.2.3. Les Regrets

Also published in 1558, Les Regrets is a collection of 191 sonnets, the majority of which were written during du Bellay's four-and-a-half-year stay in Italy. This collection is considered a masterpiece of French lyric poetry and a precursor to modern French lyricism. It expresses a profound sense of nostalgia, disillusionment, and personal emotion, particularly his longing for France and the banks of the Loire. The sonnets reveal a departure from the strict theoretical principles of the Défense, embracing a more intimate and tender style. They include satirical observations on Roman society and, after his return to Paris, appeals for patronage. His unlucky passion for a Roman lady named Faustine (who appears as Columba and Columbelle in his Latin poems) is also clearly expressed in these sonnets.

3.2.4. Divers Jeux Rustiques

Published concurrently with Antiquités de Rome and Les Regrets in 1558, Divers Jeux Rustiques is a collection of lighter, occasional, and pastoral poems. This work showcases du Bellay's versatility, offering a stylistic contrast to the more serious and reflective tones of his other major collections. It includes various poetic forms and themes, often characterized by a playful or rustic sensibility.

3.3. Other Works

Beyond his major collections, du Bellay produced other notable prose and poetic works that demonstrated his diverse talents. In 1549, he published a Recueil de poésies dedicated to Princess Marguerite. In 1552, he released a version of the fourth book of the Aeneid, along with other translations and occasional poems. Upon his return to Paris, in 1559, he published La Nouvelle Manière de faire son profit des lettres, a satirical epistle translated from the Latin of Adrien Turnèbe. This was accompanied by Le Poète courtisan (The Courtier Poet), a significant work that introduced formal satire into French poetry. Both works were published under the pseudonym J Quintil du Troussay. Le Poète courtisan was generally believed to be directed at Mellin de Saint-Gelais, though du Bellay had always maintained friendly terms with him. La Nouvelle Manière is thought to target Pierre de Paschal, a royal historiographer who had promised Latin biographies but never produced them.

In 1559, he dedicated a long and eloquent Discours au roi to Francis II, detailing the duties of a prince. This discourse, translated from a lost Latin original by Michel de l'Hôpital, is said to have secured a belated pension for the poet, though it was only published posthumously in 1567.

4. Rome and Exile

Du Bellay's extended period in Rome was a transformative experience that profoundly influenced his personal outlook and his most celebrated poetic works.

4.1. Secretary to Cardinal Du Bellay

In 1553, Joachim du Bellay traveled to Rome to serve as one of the secretaries to his kinsman, Cardinal Jean du Bellay. Cardinal du Bellay was a renowned diplomat, and Joachim's role involved various administrative duties, including managing the cardinal's creditors and household expenses. This position required him to reside in Italy for four and a half years, an experience that would shape much of his later poetry.

4.2. Experiences and Disillusionment in Rome

Initially, du Bellay had harbored a romanticized vision of Rome, the mythical city of antiquity. However, his actual experiences there led to profound disillusionment. He observed a city that, to him, had fallen into ruin and was characterized by debauchery and extravagance, a stark contrast to its glorious past. This realization, coupled with the demanding nature of his secretarial duties, fostered a deep sense of exile and regret. He found himself burdened by the mundane aspects of his service, which he frequently lamented.

Despite his disillusionment, du Bellay also formed friendships with Italian scholars and a close bond with Olivier de Magny, another exiled poet facing similar circumstances. Towards the end of his stay, he fell intensely in love with a Roman lady named Faustine, who is referred to as Columba and Columbelle in his Latin poems. This passion, expressed most clearly in his Latin verses, involved a complex relationship with Faustine, who was guarded by an old and jealous husband. His eventual conquest may have contributed to his departure for Paris in August 1557.

4.3. Influence on Later Poetry

The experiences and reflections from his Roman sojourn profoundly influenced du Bellay's subsequent poetic output. His observations of classical ruins and the contemporary state of Rome directly inspired his Antiquités de Rome, where he grappled with themes of transience and the passage of time. The sense of exile, nostalgia for France, and personal disillusionment he felt in Italy became the central themes of Les Regrets. These two collections, born from his Roman experiences, are considered his most significant works and had a lasting impact on later French literary movements, particularly influencing writers like Volney and François-René de Chateaubriand who explored similar themes of ruins and melancholic reflection.

5. Later Life and Death

Upon his return to Paris in 1557, du Bellay's health continued to decline, and he faced further personal and professional challenges leading up to his untimely death.

In Paris, du Bellay remained in the employ of Cardinal du Bellay, who delegated to him the lay patronage he still held in the diocese. However, Joachim's relationship with the cardinal became less cordial, partly due to the outspoken nature of his Regrets. He also quarreled with Eustache du Bellay, the Bishop of Paris, which further strained his ties with the cardinal. His primary patron, Marguerite de Valois, to whom he was deeply attached, had departed for Savoy, leaving him without a strong supporter in court.

Du Bellay's health was consistently weak, and his increasing deafness significantly hindered his official duties. He suffered from symptoms consistent with bone tuberculosis and chronic meningitis in his final years. On 1 January 1560, Joachim du Bellay died suddenly at the age of 38, reportedly at his desk in his study. Although there is no definitive evidence that he was ordained as a priest, he was a clerk and held various ecclesiastical preferments, including being a canon of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Consequently, he was buried in the cathedral. The claim that he was nominated Archbishop of Bordeaux in his last year of life remains unauthenticated by documentary evidence and is considered highly improbable.

6. Discovery of Remains

Recent archaeological findings at Notre-Dame Cathedral have led to the discovery and analysis of human remains, with ongoing debate surrounding the potential identification of Joachim du Bellay.

Following the devastating Cathedral fire in 2019, excavations were conducted by the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (Inrap) in April 2022. During these excavations, two lead coffins were discovered beneath the church floor. In December 2022, one coffin was identified as containing the remains of Antoine de la Porte, an 18th-century priest.

Scientific analysis of the second coffin's contents, a skeleton, revealed characteristics consistent with du Bellay's known health issues. Traces of bone tuberculosis and chronic meningitis were found on the skeleton, conditions from which the poet suffered in the last years of his life. These findings, along with the estimated age of death (around 30s) and the period (14th-18th century), led Éric Crubézy, a doctor and professor of anthropology at Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier University, to conclude in 2024 that the remains were likely those of Joachim du Bellay. The fact that his uncle, Cardinal Jean du Bellay, was also buried at Notre-Dame Cathedral further supported this theory. The skeleton also showed signs of an elongated skull, a practice of artificial cranial deformation common in western France, particularly the Deux-Sèvres region, until the early 20th century. Additionally, evidence suggested the individual was skilled in horse riding and regularly used swords or spears. The cause of death was attributed to chronic meningitis resulting from tuberculosis, which caused all teeth to fall out. The body also showed signs of embalming and incisions to the skull and chest.

However, subsequent isotope analysis of the skeleton has introduced contradictory evidence. These analyses suggest that the individual originated from the west of France, while du Bellay grew up in the Anjou region in the east. Due to this discrepancy, some excavators propose an alternative identification, suggesting the remains might belong to Édouard de la Madeleine, a 16th-century French knight. The debate regarding the definitive identification of the remains continues.

7. Legacy and Influence

Joachim du Bellay's work left an indelible mark on French literature, language, and poetry, earning him a significant place in literary history. His contributions were crucial to the French Renaissance and the development of a distinct national poetic tradition.

His most profound impact stems from Défense et illustration de la langue française, which served as a powerful manifesto for the French language. This work not only advocated for French as a vehicle for high art but also laid the theoretical groundwork for the Pléiade's reforms, influencing linguistic policy and literary practice for generations. Du Bellay's emphasis on enriching the French vocabulary and developing new poetic forms helped to solidify French as a robust and expressive literary language.

Through his poetry, particularly Olive, he was instrumental in acclimatizing the sonnet form in France, making it a popular and enduring poetic structure. His later collections, Antiquités de Rome and Les Regrets, are celebrated for their personal, melancholic, and lyrical qualities, marking a shift towards a more introspective and modern form of lyric poetry. These works, born from his experiences of disillusionment and exile, resonated deeply and influenced subsequent literary movements and poets who explored similar themes of ruins, nostalgia, and personal reflection. His satirical work, Le Poète courtisan, also introduced formal satire into French poetry.

Critics often highlight du Bellay's unique blend of classical erudition with a distinctly French sensibility, a characteristic that set him apart even within the Pléiade. His ability to convey profound personal emotion with elegant verse, especially in Les Regrets, is widely regarded as a major contribution to the development of French lyricism. His legacy is that of a poet who not only theorized about the potential of his native tongue but also demonstrated its capabilities through his own masterful and innovative works.