1. Overview

Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667) was a prominent cleric and prolific author of the Church of England, achieving fame during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. He is often referred to as the "Shakespeare of Divines" due to his poetic style of expression and is widely regarded as one of the greatest English prose writers. His works, particularly The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living and Holy Dying, significantly influenced devotional literature and figures like John Wesley, while his advocacy for religious tolerance left a lasting impact on theological discourse.

2. Early Life and Education

Jeremy Taylor was born in Cambridge, the son of Nathaniel, a barber. He was baptized on 15 August 1613 at Holy Trinity Church, Cambridge. His father, who was educated, taught him grammar and mathematics at home. Taylor then attended the Perse School, Cambridge, before enrolling at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1630 or 1631 and a Master of Arts degree in 1634. Despite being below the canonical age, he took holy orders in 1633 and accepted an invitation from Thomas Risden, a former fellow student, to temporarily serve as a lecturer at St Paul's Cathedral. His diligence as a student is evident in the extensive learning he commanded with ease in his later years.

3. Career under Laud and Royalist Affiliation

Jeremy Taylor's early career was significantly shaped by the patronage of William Laud, who was then Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud invited Taylor to preach in his presence at Lambeth and subsequently took the young man under his protection. Although Taylor did not vacate his fellowship at Cambridge until 1636, he spent much of his time in London, as Laud desired to provide him with better opportunities for study and improvement than constant preaching would allow.

In November 1635, Laud nominated him for a fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford. While at Oxford, he was admired and loved. He spent little time there, however, as he became chaplain to Archbishop Laud and subsequently chaplain in ordinary to King Charles I. During his time at Oxford, Taylor engaged in discussions with William Chillingworth, who was then working on his major treatise, The Religion of Protestants. These discussions may have influenced Taylor's inclination towards the liberal intellectual movements of his era.

After two years in Oxford, in March 1638, Taylor was presented by William Juxon, the Bishop of London, to the rectory of Uppingham in Rutland. There, he settled into the duties of a country priest. In the following year, he married Phoebe Langsdale. In the autumn of the same year, he was appointed to preach at St Mary's on the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot. He reportedly used this occasion to address suspicions, which persisted throughout his life, of a secret leaning towards Roman Catholicism. This suspicion largely stemmed from his close association with Christopher Davenport, also known as Francis a Sancta Clara, a learned Franciscan friar who served as chaplain to Queen Henrietta. His known connection with Laud and his ascetic habits may have further fueled these rumors.

More serious consequences arose from his steadfast support for the Royalist cause during the English Civil War. As the author of The Sacred Order and Offices of Episcopacy or Episcopacy Asserted against the Arians and Acephali New and Old (1642), Taylor could hardly expect to retain his parish, which was eventually sequestered in 1644. Taylor likely accompanied King Charles I to Oxford. In 1643, Charles I presented him with the rectory of Overstone, Northamptonshire, placing him in close proximity to his friend and patron, Spencer Compton, 2nd Earl of Northampton.

4. Period of Imprisonment and Writing

During the fifteen years following the parliamentary victory, Taylor's movements are not easily traced. He appears to have been in London during the final weeks of Charles I in 1649, from whom he is said to have received a watch and jewels that adorned the ebony case of the King's Bible. Taylor had been captured along with other Royalists during the siege of Cardigan Castle on 4 February 1645.

By 1646, he was involved in running a school at Newton Hall, located in the parish of Llanfihangel Aberbythych, Carmarthenshire, in partnership with two other dispossessed clergymen. It was there that he became the private chaplain to Richard Vaughan, 2nd Earl of Carbery, benefiting from his hospitality at his mansion, Golden Grove. This estate is famously immortalized in the title of Taylor's enduringly popular devotional manual. It was at Golden Grove that Taylor composed some of his most distinguished works, including The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living (1650) and The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying (1651). Alice, the third Lady Carbery, served as the inspiration for the Lady character in John Milton's Comus.

Taylor's first wife, Phoebe Langsdale, passed away in early 1651. He subsequently married Joanna Bridges or Brydges, though the assertion that she was a natural daughter of Charles I lacks substantial evidence. She possessed a considerable estate at Mandinam, Carmarthenshire, which was likely diminished by Parliamentarian requisitions. Several years after their marriage, they relocated to Ireland.

Taylor made occasional appearances in London, often in the company of his friend John Evelyn, whose Diary and correspondence frequently mention Taylor. He experienced imprisonment three times during this period: first in 1645 for an ill-advised preface to his Golden Grove; again from May to October 1655 at Chepstow Castle, though the specific charge remains unclear; and a third time in the Tower in 1657, due to the indiscretion of his publisher, Richard Royston, who had adorned Taylor's Collection of Offices with a print depicting Christ in a praying posture.

5. Bishop in Ireland and the Restoration

Taylor likely departed Wales in 1657, having ceased his direct association with Golden Grove two years prior. In 1658, through the good offices of his friend John Evelyn, Taylor was offered a lectureship in Lisburn, County Antrim, by Edward Conway, 2nd Viscount Conway. Initially, he hesitated to accept a position that required him to share duties with a Presbyterian, expressing his concern that he and a Presbyterian would be "like Castor and Pollux, the one up the other downe," and noting the meager salary. However, he was eventually persuaded to accept the role and found a congenial retreat at his patron's property in Portmore, on Lough Neagh.

Upon the Stuart Restoration, instead of being recalled to England, which he likely anticipated and certainly desired, Taylor was appointed to the see of Down and Connor. Shortly thereafter, he was given the additional responsibility of overseeing the adjacent diocese of Dromore. As bishop, he commissioned the construction of a new cathedral at Dromore for the Dromore diocese in 1661. He was also made a member of the privy council of Ireland and, in 1660, became Vice-Chancellor of the University of Dublin. None of these positions were sinecures.

Regarding the university, Taylor observed: "I found all things in a perfect disorder ... a heap of men and boys, but no body of a college, no one member, either fellow or scholar, having any legal title to his place, but thrust in by tyranny or chance." Consequently, he vigorously undertook the task of formulating and enforcing regulations for the admission and conduct of university members, as well as establishing new lectureships.

His episcopal duties proved even more demanding. At the time of the Restoration, there were approximately seventy Presbyterian ministers in northern Ireland, most of whom hailed from western Scotland and harbored a strong dislike for Episcopacy, characteristic of the Covenanting party. Taylor, writing to James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde shortly after his consecration, remarked, "I perceive myself thrown into a place of torment." While his letters may have somewhat exaggerated the danger he faced, there is no doubt that his authority was met with resistance and his overtures were rejected. This period presented Taylor with a prime opportunity to demonstrate the wise toleration he had previously advocated. However, the new bishop offered the Presbyterian clergy only the alternative of submission to episcopal ordination and jurisdiction or deprivation. As a result, at his first visitation, he declared thirty-six churches vacant, and repossession was secured under his orders. Despite these challenges, many of the gentry were reportedly won over by his undeniable sincerity, devotedness, and eloquence.

He was less successful with the Roman Catholic population. Not knowing the English language and firmly attached to their traditional forms of worship, they were nevertheless compelled to attend a service they considered profane and conducted in a language they could not understand. As Reginald Heber noted, "No part of the administration of Ireland by the English crown has been more extraordinary and more unfortunate than the system pursued for the introduction of the Reformed religion." At the urging of the Irish bishops, Taylor undertook his final major work, the Dissuasive from Popery (published in two parts, 1664 and 1667). However, as he himself seemed partly aware, he might have achieved his goal more effectively by adopting the methods of James Ussher and William Bedell, encouraging his clergy to learn the Irish language.

During this period, he was married a second time to Joanna Brydges, supposedly a natural daughter of Charles I. From this marriage, two daughters were born: Mary, who went on to marry Archbishop Francis Marsh and had issue and Joanna, who married Edward Harrison, a Member of Parliament for Lisburn, and had issue. From his father-in-law, Marsh inherited a silver watch, which was said to have been a gift from Charles I; this watch remained in the family of Marsh's great-grandson, Francis Marsh, a barrister.

6. Major Writings and Literary Style

Jeremy Taylor produced an extensive body of work, encompassing theological treatises, devotional manuals, and sermons, all characterized by his distinctive and highly praised literary style.

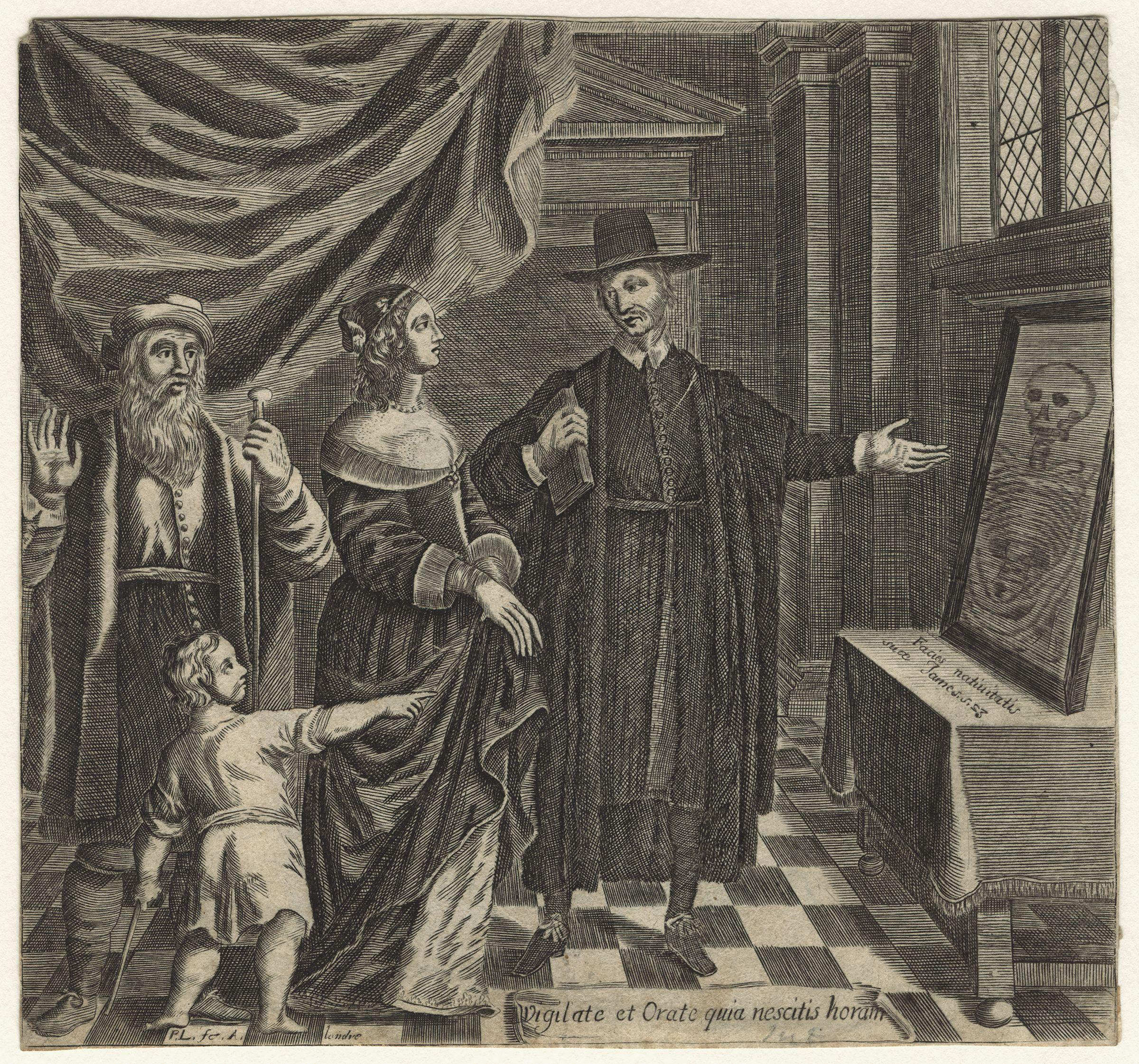

Among his most renowned works are his twin devotional manuals: The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living (1650) and The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying (1651). Holy Living served as a guide to Christian practice, detailing the means to acquire virtues, remedies against vices, strategies for resisting temptations, and prayers encompassing the full duty of a Christian. Holy Dying proved to be even more popular, offering reflections on mortality and preparation for death. These books were particular favorites of John Wesley and were admired for their prose by literary figures such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, and Thomas de Quincey.

In 1657, in response to a query from his friend Katherine Philipps (known as "the matchless Orinda") about the Christian authorization of deep friendship, Taylor dedicated to her his Discourse of the Nature, Offices and Measures of Friendship. His comprehensive work, Ductor Dubitantium, or the Rule of Conscience ... (1660), was intended to be the definitive manual on casuistry and ethics for Christians. Other significant publications include A Discourse of the Liberty of Prophesying (1646), a notable early plea for religious toleration, and Great Exemplar ... a History of ... Jesus Christ (1649), inspired by his earlier interactions with the Earl of Northampton.

His theological works also included Apology for Authorised and Set Forms of Liturgy against the Pretence of the Spirit (1649), Clerus Domini: or, A Discourse of the Divine Institution, Necessity, Sacrednesse, and Separation of the Office Ministerial (1651), and The Real Presence and Spirituall of Christ in the Blessed Statement Proved Against the Doctrine of Transubstantiation. (1654). His devotional collection, Golden Grove; or a Manuall of Daily Prayers and Letanies ... (1655), and Unum Necessarium (1655), which addressed the doctrine of repentance but caused offense to Presbyterians due to its perceived Pelagianism, further illustrate his diverse output. In 1660, he published The Worthy Communicant; or a Discourse of the Nature, Effects, and Blessings consequent to the worthy receiving of the Lords Supper .... Taylor is also credited with compiling Contemplations of the State of Man in this Life, and in that which is to Come (1684), an abridgement of Juan Eusebio Nieremberg's work De la diferencia entre lo temporal y lo eterno, y Crisol de Desengaños (1640), translated into English by Vivian Mullineaux in 1672. Taylor's works were also translated into Welsh by Nathanael Jones.

Taylor's literary style is renowned for its poetic quality, leading to his epithet as the "Shakespeare of Divines." His prose is characterized by solemn yet vivid rhetoric, elaborate periodic sentences, and a meticulous attention to the musicality and rhythm of words. An example of his distinctive style can be found in Holy Dying:

As our life is very short, so it is very miserable; and therefore it is well that it is short. God, in pity to mankind, lest his burden should be insupportable and his nature an intolerable load, hath reduced our state of misery to an abbreviature; and the greater our misery is, the less while it is like to last; the sorrows of a man's spirit being like ponderous weights, which by the greatness of their burden make a swifter motion, and descend into the grave to rest and ease our wearied limbs; for then only we shall sleep quietly, when those fetters are knocked off, which not only bound our souls in prison, but also ate the flesh until the very bones opened the secret garments of their cartilages, discovering their nakedness and sorrow.

Possessing a genuinely poetic temperament, fervent and agile in feeling, and a prolific imagination, Taylor also demonstrated keen insight and wit derived from his varied interactions with people. All his talents were channeled into influencing others through his effortless command of a style rarely matched in dignity and color. While possessing the majesty, stately elaboration, and musical rhythm of John Milton's finest prose, Taylor's style is further enlivened and brightened by an astonishing array of felicitous illustrations, ranging from the most homely and concise to the most dignified and elaborate. His sermons, in particular, are rich with quotations and allusions that appear to spontaneously arise, though they may have occasionally perplexed his listeners. This seeming pedantry is, however, redeemed by the clear practical objective of his sermons, the noble ideal he presented to his audience, and his skill in addressing spiritual experiences and advocating for virtuous living.

7. Theological and Philosophical Contributions

Jeremy Taylor's enduring fame rests more on the popularity of his sermons and devotional writings than on his direct influence as a systematic theologian or his prominence as an ecclesiastic. His intellectual approach was neither strictly scientific nor speculative; he was more drawn to questions of casuistry-the application of general ethical principles to particular cases-rather than the abstract problems of pure theology. Despite his extensive reading and remarkable memory, which allowed him to retain a wealth of historical theological material, these resources were not always subjected to rigorous critical analysis. His immense learning served him primarily as a rich source of illustrations or as an arsenal from which to select the most effective arguments against opponents, rather than as a quarry for constructing a fully designed and enduring edifice of systematized truth.

Indeed, Taylor held a rather limited faith in the human mind's capacity as an instrument for discovering absolute truth. He famously asserted that theology is "rather a divine life than a divine knowledge," emphasizing the practical and experiential aspects of faith over purely intellectual understanding.

His most significant plea for religious toleration, articulated in A Discourse of the Liberty of Prophesying, is founded on the premise that it is impossible to elevate theology to the status of a demonstrable science. He argued that it is unrealistic to expect everyone to hold the same opinions, stating, "It is impossible all should be of one mind. And what is impossible to be done is not necessary it should be done." While acknowledging that differences of opinion are inevitable, Taylor distinguished heresy not as an error of understanding but as an error of the will. He advocated for individuals to resolve minor theological questions through their own reason, but he did set certain boundaries for toleration. These exclusions included anything that contradicted the fundamental tenets of faith, violated principles of good conduct and obedience, or threatened human society and the legitimate public interests of political bodies. Taylor believed that peace could be achieved if people refrained from labeling every opinion as "religion" and every theological superstructure as "fundamental articles" of faith. Regarding the propositions put forth by sectarian theologians, he famously remarked that "confidence was the first, and the second, and the third part," implying that their assertions were often based more on conviction than on demonstrable truth.

8. Personal Life and Family

Jeremy Taylor married Phoebe Langsdale, and together they had six children: William (who died in 1642), George (whose fate is uncertain), Richard (who died around 1656 or 1657), Charles, Phoebe, and Mary. After Phoebe's death in early 1651, Taylor married Joanna Bridges or Brydges. While it has been claimed that Joanna was a natural daughter of Charles I, there is no strong evidence to support this assertion. From his second marriage, Taylor had two daughters: Mary, who later married Archbishop Francis Marsh and had descendants, and Joanna, who married Edward Harrison, a Member of Parliament for Lisburn, and also had descendants. Archbishop Marsh inherited a silver watch from his father-in-law, which was said to have been a gift from Charles I; this watch remained in the family of Marsh's great-grandson, Francis Marsh, a barrister.

Though it has been asserted that Jeremy Taylor was a lineal descendant of Rowland Taylor, this claim has not been definitively proven. Through his daughter Mary, who married Archbishop Francis Marsh, Jeremy Taylor has numerous descendants.

9. Death and Commemoration

Jeremy Taylor died in Lisburn, Ireland, on 13 August 1667. He was laid to rest at Dromore Cathedral, where an apsidal chancel was constructed in 1870 directly over the crypt where he was buried.

Jeremy Taylor is honored in the liturgical calendars of several Anglican churches. He is commemorated on August 13 in the Church of England, the Anglican Church of Canada, the Scottish Episcopal Church, the Anglican Church of Australia, and the Episcopal Church of the United States.

10. Evaluation and Influence

Jeremy Taylor's enduring reputation is primarily sustained by the widespread popularity of his sermons and devotional writings, rather than his direct impact as a systematic theologian or his ecclesiastical significance. He is widely celebrated as the "Shakespeare of Divines" due to his profoundly poetic and eloquent style, which has cemented his place as one of the greatest prose writers in the English language. His literary craftsmanship, characterized by solemn yet vivid rhetoric, elaborate periodic sentences, and a keen sense of rhythm and musicality, garnered admiration from prominent literary figures such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, and Thomas de Quincey.

His devotional manuals, particularly The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living and Holy Dying, became enduring favorites and exerted a significant influence on subsequent generations of readers and theologians. Notably, these works profoundly impacted John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, and continued to shape devotional literature for centuries. While his contributions to casuistry and his advocacy for religious toleration, as expressed in A Discourse of the Liberty of Prophesying, were significant, his perceived Pelagianism in works like Unum Necessarium did draw criticism from Presbyterians. Despite any historical controversies, Taylor's unique blend of profound spirituality, intellectual depth, and unparalleled literary artistry ensures his lasting legacy in English literature and Christian thought.