1. Overview

John Wesley (ˈwɛsliWESS-leeEnglish; June 28, 1703 - March 2, 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. His work laid the foundation for the independent Methodist movement, which continues to thrive globally. Wesley's teachings, collectively known as Wesleyan theology, emphasize a balance between personal faith and social action, advocating for the holistic transformation of individuals and society.

Educated at Charterhouse School and Christ Church, Oxford, Wesley was ordained an Anglican priest in 1728. He led the "Holy Club" at Oxford, a group dedicated to devout Christian living and charitable work. After an unsuccessful two-year ministry in Savannah, Georgia, he returned to London and experienced a profound spiritual conversion in 1738, often referred to as his "heart strangely warmed" moment. This pivotal experience led him to embrace Arminianism and embark on an extensive open-air preaching ministry across Great Britain and Ireland, reaching wide audiences beyond traditional church walls.

Wesley was instrumental in forming and organizing small Christian groups, known as societies and classes, which fostered intensive personal accountability and religious instruction. He controversially appointed itinerant, unordained evangelists, including women, to expand the movement's reach. Under his leadership, Methodists became prominent advocates for social justice issues of their time, including the abolition of slavery, prison reform, and support for the poor. His commitment to social welfare and human rights reflected a progressive stance that challenged the prevailing norms, positioning him as a significant figure in the development of social conscience. Although he remained an Anglican priest throughout his life, the organizational structures he developed for the Methodist societies eventually led to their separation from the Church of England after his death.

2. Early Life and Background

John Wesley was born on June 28, 1703 (June 17, 1703 Old Style), in Epworth, Lincolnshire, England, approximately 23 mile (37 km) northwest of Lincoln, England. He was the fifteenth of nineteen children born to Samuel Wesley and Susanna Wesley (née Annesley). Only nine of their children survived infancy.

2.1. Family and Upbringing

Samuel Wesley, a graduate of the University of Oxford and a poet, served as the rector of Epworth from 1696. In 1689, he married Susanna, the twenty-fifth child of Samuel Annesley, a dissenting minister. Both Samuel and Susanna had become members of the Church of England as young adults.

Wesley's parents provided their children with their early education at home, a common practice for families of their social standing. Each child, including the girls, was taught to read as soon as they turned five years old. They were expected to become proficient in Latin and Greek and to have memorized significant portions of the New Testament. Susanna Wesley, a highly intellectual woman proficient in Latin, Greek, and French, personally examined each child before the midday meal and before evening prayers. Children were not permitted to eat between meals and were interviewed individually by their mother one evening each week for intensive spiritual instruction. This disciplined upbringing, particularly influenced by his mother, instilled in Wesley a methodical and studious approach to life and faith. John Wesley especially cherished his Thursday night meetings with his mother, reflecting on them fondly throughout his life. At age 11, in 1714, Wesley was sent to the Charterhouse School in London, where he continued the studious, methodical, and religious life he had been trained for at home.

2.2. Epworth Rectory Fire

A significant childhood event that left an indelible impression on Wesley was a rectory fire that occurred on February 9, 1709, when he was five years old. Sometime after 11:00 PM, the rectory roof caught fire. Sparks falling on the children's beds and cries of "fire" from the street roused the family, who managed to lead all their children out of the house except for John, who was left stranded on an upper floor. With the stairs aflame and the roof on the verge of collapse, Wesley was lifted out of a window by a parishioner standing on another man's shoulders, just as the roof collapsed. His father, Samuel, had reportedly given up hope and prayed for his son's soul.

Wesley later used the phrase, "a brand plucked out of the fire," quoting Zechariah 3:2, to describe this incident. This childhood deliverance became a significant part of the Wesley legend, interpreted by his family and later by himself as a sign of his special destiny and extraordinary work. The Wesley family also reported a haunting of the Old Rectory, Epworth between 1716 and 1717, experiencing noises and apparitions they attributed to a ghost named 'Old Jeffery'.

3. Education and Oxford Years

John Wesley's academic journey at Charterhouse School and Oxford University was foundational to his intellectual and spiritual formation, shaping his disciplined approach to life and his early theological explorations.

3.1. Charterhouse School

In 1714, at the age of 11, Wesley enrolled at Charterhouse School in London. His time there, under the mastership of John King from 1715, was characterized by a studious and methodical routine, mirroring the disciplined environment of his childhood home. Although the conditions at Charterhouse were not luxurious, Wesley adapted to the rigorous academic and daily life, which further solidified his habits of diligent study and religious observance.

3.2. Christ Church, Oxford

In June 1720, Wesley entered Christ Church, Oxford. He graduated in 1724 with a Bachelor of Arts degree and continued his studies at Christ Church to pursue a Master of Arts degree. During this period, he engaged deeply with theological and devotional texts. He was particularly influenced by the writings of Thomas à Kempis's The Imitation of Christ and Jeremy Taylor's Rules and Exercises for Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works impressed upon him the importance of inner piety and the need for true faith to permeate all thoughts, words, and actions. This early exposure to Christian mysticism and devout living laid the groundwork for his later spiritual quest.

3.3. Lincoln College and Ordination

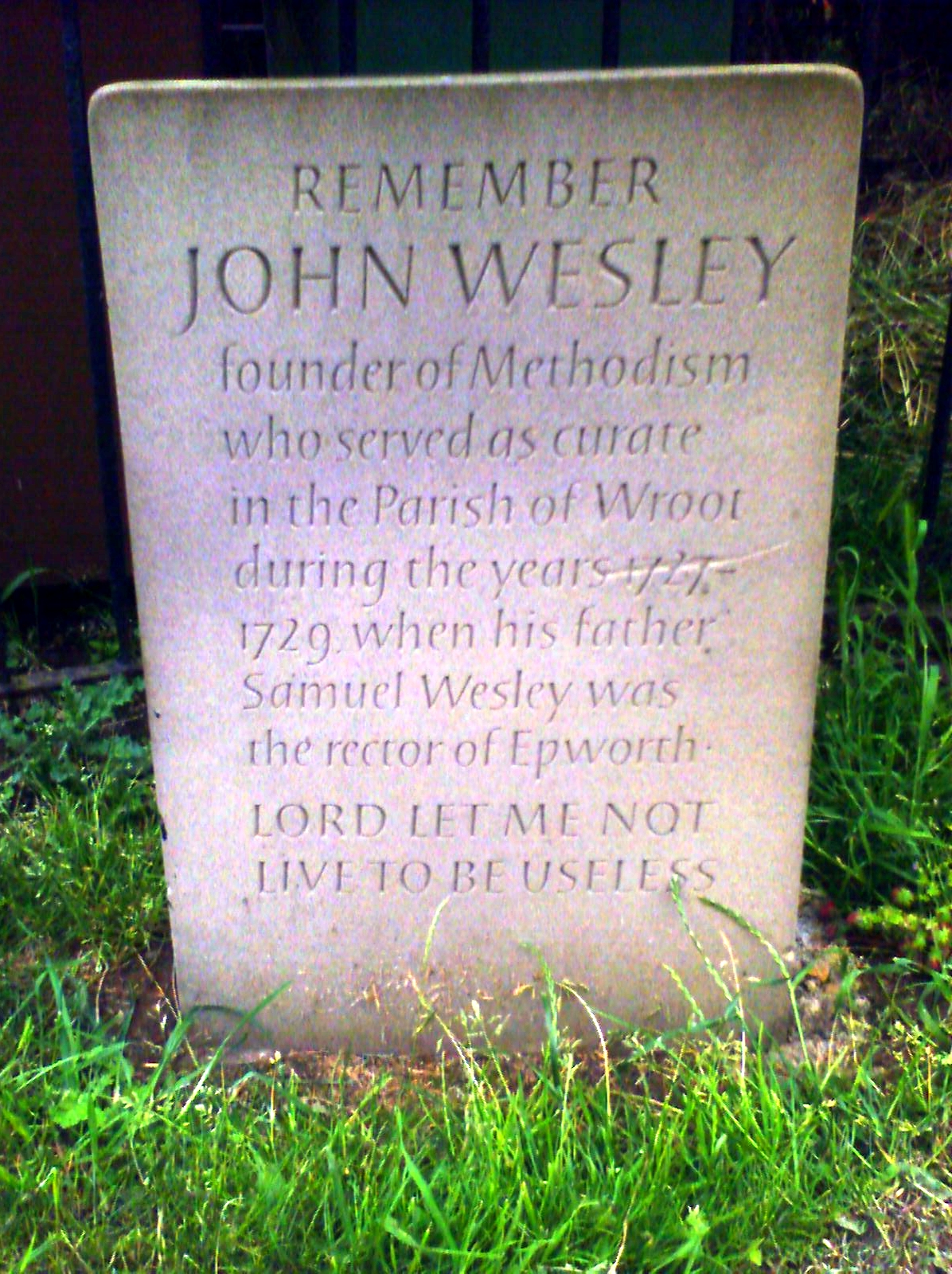

On September 25, 1725, Wesley was ordained a deacon by Bishop John Potter of Oxford. This was a necessary step towards becoming a fellow and tutor at the university. On March 17, 1726, Wesley was unanimously elected a fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford. This position granted him a room at the college and a regular salary, ranging from 18 GBP to 80 GBP annually, averaging around 30 GBP. While continuing his studies, he taught Greek and philosophy, lectured on the New Testament, and moderated daily disputations at the university.

In August 1727, after completing his master's degree, Wesley returned to Epworth to assist his father in serving the neighboring parish of Wroot. He was ordained a priest on September 22, 1728, again by Bishop John Potter, and served as a parish curate for two years. During this time, he continued his rigorous spiritual discipline, seeking "holiness of heart and life" through abstemious living, diligent Scripture study, and charitable acts, often depriving himself to give alms. He resolved to keep God's law as sacredly as possible, believing that obedience would lead to salvation. In November 1729, he returned to Oxford at the request of the Rector of Lincoln College to maintain his status as a junior fellow.

4. The Holy Club

Upon John Wesley's return to Oxford in November 1729, he became the leader of a small group that his younger brother, Charles Wesley, had formed. This group, dedicated to intense study and devout Christian living, became known derisively as the "Holy Club."

4.1. Formation and Activities

The Holy Club was founded by Charles Wesley, along with two fellow students, William Morgan and Robert Kirkham, for the purpose of studying and pursuing a devout Christian life. When John Wesley returned, he assumed leadership, and the group grew in both number and commitment. Their daily routine was highly structured: they met from 6:00 AM to 9:00 AM for prayer, psalms, and reading the Greek New Testament. They prayed for several minutes every waking hour and dedicated each day to a special virtue.

The club members adhered to practices that went beyond the typical Anglican worship of the time. While the Church of England generally prescribed Communion three times a year, the Holy Club received Communion every Sunday, following the practice of the early church. They also observed fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays until 3:00 PM (nones), a common practice in the ancient church.

From August 1730, the group expanded their activities to include significant social outreach, regularly visiting prisoners in gaol. This initiative, proposed by William Morgan, became a central part of their ministry. They preached to prisoners, educated them, and provided relief for jailed debtors, even repaying debts to secure their release. They also cared for the sick. In 1732, Wesley compiled "A Collection of Forms of Prayer for everyday in the week" for the Holy Club, which included a "Scheme of Self-examination" for daily introspection. The club strictly followed Wesley's rules and prayer book.

4.2. Criticism and Nicknames

Given the low ebb of spirituality in Oxford at the time, Wesley's group provoked a strong negative reaction from the university community, who viewed them as religious "enthusiasts," a term that implied religious fanatics. University wits derisively styled them the "Holy Club." Other nicknames included "Bible Moths," "Supererogation Men" (a term from Roman Catholicism referring to good works beyond what is required for salvation, implying they believed in salvation by works), "Sacramentarians," "Primitive Church," and "Enthusiasts." Wesley himself noted that the term "Methodist" was used by "some of our neighbors [who] are pleased to compliment us." This name was later adopted by an anonymous author in a 1733 pamphlet describing the group as "The Oxford Methodists."

Opposition intensified following the mental breakdown and death of William Morgan, a group member. In response to accusations that "rigorous fasting" had hastened Morgan's death, Wesley clarified that Morgan had stopped fasting a year and a half prior. Wesley viewed the contempt and ridicule directed at him and his group as a mark of a true Christian, writing to his father, "Till he be thus contemned, no man is in a state of salvation." Despite the criticism, the Holy Club also provided support to controversial figures, such as Thomas Blair, who was found guilty of sodomy in 1732. Wesley continued to support Blair, who was notorious among townspeople and fellow prisoners.

Wesley meticulously cultivated his inner holiness, or sincerity, as evidence of his Christian faith. His "General Questions," developed in 1730, evolved into an elaborate grid by 1734, where he recorded his daily activities hour-by-hour, resolutions kept or broken, and ranked his hourly "temper of devotion" on a scale of 1 to 9. The Holy Club's activities in Oxford laid the groundwork for the larger Methodist movement that Wesley would later initiate after his conversion experience.

5. Mission to Georgia

In 1735, John Wesley embarked on a mission to the American colony of Georgia, a period that would prove to be deeply challenging and transformative for his spiritual journey.

5.1. Voyage and Arrival

On October 14, 1735, Wesley and his brother Charles sailed on The Simmonds from Gravesend, Kent, bound for Savannah, Georgia, in the Province of Georgia. Their journey was at the request of James Oglethorpe, who had founded the colony in 1733 and sought a minister for the newly formed Savannah parish, a town laid out according to the famous Oglethorpe Plan. Accompanying them were Benjamin Ingham of Oxford's Queen's College and Charles Delamotte, son of a London merchant. They were also joined by 26 Moravian settlers from the Herrnhut labor community in Germany, led by Bishop David Nitschmann.

The voyage across the Atlantic, lasting nearly five months, was fraught with peril. The ship narrowly avoided capsizing multiple times, with waves breaking cabin windows and the mast snapping. During these moments of extreme danger, while the English passengers panicked, the Moravians remained calm, singing hymns and praying. This profound experience deeply impressed Wesley, leading him to believe that the Moravians possessed an inner strength and faith that he lacked. He was particularly influenced by their deep faith and spirituality rooted in Pietism. This encounter sparked a personal quest for a more profound and assured faith.

Wesley arrived in the colony on February 6, 1736. Although he was intended to be the second Anglican priest in Georgia, the previous priest, Samuel Quincy, had not yet departed, leaving Wesley without a parsonage. Consequently, Wesley and Charles Delamotte resided in the Moravian barracks, allowing Wesley to observe their devout lifestyle firsthand. He formed a deep connection with August Spangenberg, a Moravian leader, who significantly influenced him. Spangenberg famously challenged Wesley with questions about his personal assurance of salvation and his knowledge of Jesus Christ as his personal Savior, prompting Wesley to reflect on his own spiritual state and confess his lack of certainty.

5.2. Ministry and Challenges

Wesley approached his Georgia mission as a High churchman, aspiring to revive "primitive Christianity" in a new, untainted environment. His primary goal was to evangelize the Native American people. However, a severe shortage of clergy in the colony largely confined his ministry to the European settlers in Savannah. While his time in Georgia is often deemed a failure compared to his later successes, he did gather a devoted group of Christians who met in small religious societies, and attendance at Communion increased during his nearly two years as parish priest of Christ Church.

Despite these efforts, Wesley's High Church practices proved controversial among the colonists. He insisted on rebaptizing children of Nonconformists and performing baptisms by triple immersion. He also strictly discriminated against Nonconformists, refusing to officiate at their funerals. His rigid adherence to Anglican rubrics and his conservative pastoral style caused considerable friction. His brother Charles, who had started his ministry in Frederica, also faced significant challenges, including malicious threats and actions from colonists, leading him to abandon his colonial work and return to England in August 1736 after only six months. John Wesley then began making regular visits to Frederica to fill the pastoral void, but the situation there was even worse than in Savannah, and he was forced to cease his ministry in Frederica by January 1737.

5.3. Relationship with Sophia Hopkey

A significant personal challenge arose when Wesley became romantically involved with Sophia Hopkey, the 18-year-old niece of Chief Magistrate Thomas Causton, whom Governor Oglethorpe had introduced to him in 1736. Despite falling in love, Wesley hesitated to marry her, torn between his commitment to missionary work among Native Americans and his interest in the practice of clerical celibacy in early Christianity. His internal conflict and indecision led to Sophia's marriage to William Williamson on March 12, 1737, after she had given Wesley an ultimatum.

Following her marriage, Wesley believed Sophia's zeal for Christian practice declined. In a strict application of the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer, Wesley publicly humiliated her by denying her Communion on August 7, 1737, because she had failed to notify him in advance of her intention to take it. This action was widely perceived as an act of personal spite rather than priestly duty, especially given her uncle's prominent position. The incident escalated into legal proceedings against Wesley, with ten charges filed against him by a 26-member jury. Facing an unlikely resolution and increasing disillusionment, Wesley fled the colony on December 2, 1737, and returned to England. His mission in Georgia, lasting one year and nine months, was ultimately considered a failure.

Despite the personal and ministerial setbacks, one significant accomplishment of Wesley's Georgia mission was the publication of his Collection of Psalms and Hymns. This was the first Anglican hymnal published in America and the first of many hymn books Wesley would publish, including five hymns he translated from German.

5.4. Return to England

Wesley arrived back in England on February 1, 1738, deeply depressed and disheartened by his experiences in Georgia. During his return voyage, he reflected on his own religious faith, realizing his spiritual inadequacy despite his commitment to Christ. He felt unfit to preach, particularly after witnessing the unwavering faith of the Moravians during the storm. His journal entries from this period reveal his profound spiritual crisis and fear of death, contrasting sharply with the Moravians' calm assurance. Upon his return to London, he submitted his resignation as a missionary to Oglethorpe and the Georgia Trustees. Without a clear direction, he stayed with his brother Charles's friend, James Hutton, where he would soon encounter a pivotal figure in his spiritual awakening.

6. Spiritual Awakening and the Birth of Methodism

Wesley's return to England marked a period of intense spiritual crisis that culminated in a transformative experience, leading to the birth of Methodism.

6.1. Aldersgate Experience

Upon his return, Wesley sought counsel from Peter Boehler, a young Moravian missionary temporarily in England awaiting permission to depart for Georgia. Boehler challenged Wesley on his lack of "saving faith" and urged him to "preach faith until you have it." Wesley initially struggled to grasp Boehler's emphasis on instantaneous conversion and assurance of salvation, but he diligently studied the Greek New Testament to verify these concepts. By late April, he accepted Boehler's explanation of saving faith, which connected justification (legal change) with regeneration (participatory change), and agreed to the idea of immediate conversion. He cried out, "Now my disputing is over. Lord, help my unbelief!"

Wesley's noted "Aldersgate experience" occurred on May 24, 1738, at a Moravian meeting in Aldersgate Street, London. The previous week, he had been deeply impressed by a sermon by John Heylyn at St Mary le Strand. Earlier on May 24, he heard the choir at St Paul's Cathedral singing Psalm 130, "Out of the depths have I called unto thee, O Lord." Still feeling depressed, Wesley reluctantly attended the evening meeting. As someone read Martin Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans, which explained the nature of faith and justification by faith, Wesley recounted in his journal:

"In the evening I went very unwillingly to a society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther's Preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death."

This moment, often referred to as his "Evangelical Conversion," revolutionized the character and method of his ministry. A few weeks later, Wesley preached a sermon on the doctrine of personal salvation by faith, followed by another on God's grace, "free in all, and free for all." This event is considered monumental, with Daniel L. Burnett stating that "Without it, the names of Wesley and Methodism would likely be nothing more than obscure footnotes in the pages of church history." May 24 is commemorated in Methodist churches as Aldersgate Day.

6.2. Association with Moravians

Following his Aldersgate experience, Wesley allied himself with the Moravian society in Fetter Lane, London. In August 1738, he traveled to Germany to visit Herrnhut in Saxony, the Moravian headquarters, to study their practices and theology firsthand. Upon his return to England, Wesley drafted rules for the "bands" into which the Fetter Lane Society was divided and published a collection of hymns for them. He frequently met with this and other religious societies in London, but found most parish churches closed to his preaching in 1738 due to his new evangelical fervor and unconventional methods.

6.3. Open-Air Preaching

Wesley's Oxford friend, the evangelist George Whitefield, faced similar exclusion from the churches of Bristol upon his return from America. Bristol was experiencing rapid industrial and commercial growth, leading to social unrest and religious ferment. About a fifth of the population were English Dissenters, and many Anglicans were receptive to Wesley's message. In February 1739, Whitefield began preaching in the open air to miners in the neighboring village of Kingswood, South Gloucestershire, and later at Whitefield's Tabernacle.

Wesley initially hesitated to adopt this bold step, as he had always been "tenacious of every point relating to decency and order" in Anglican liturgy, believing that "the saving of souls [would be] almost a sin if it had not been done in a church." However, overcoming his scruples, he preached his first open-air sermon at Whitefield's invitation at a brickyard near St Philip's Marsh, Bristol, on April 2, 1739. He recognized that open-air services were highly effective in reaching men and women who would not enter most churches. From then on, he seized every opportunity to preach wherever an assembly could be gathered, even using his father's tombstone at Epworth as a pulpit on more than one occasion.

His field preaching aimed to evoke repentance, pray for conversion, and address the spiritual needs of thousands, often leading to powerful emotional responses. For fifty years, Wesley continued this practice-entering churches when invited, and preaching in fields, halls, cottages, and chapels when churches would not receive him.

Late in 1739, Wesley's theological differences with the Moravians in London, particularly their support for quietism, led him to break with the Fetter Lane Society. He decided to form his own followers into a separate society, writing, "Thus, without any previous plan, began the Methodist Society in England." He soon established similar societies in Bristol and Kingswood, and he and his associates made converts wherever they went.

7. Development of the Methodist Movement

The Methodist movement, under Wesley's dynamic leadership, rapidly grew and developed into a highly organized religious structure, establishing a distinct identity and expanding its reach across Great Britain and Ireland.

7.1. Formation of Societies and Classes

As the number of converts increased, Wesley recognized the need for structured spiritual accountability and discipleship. He began to organize his followers into "societies," which were further divided into smaller "classes" and "bands." These groups were designed for intensive personal accountability, mutual encouragement, and religious instruction. Members were given "tickets" with their names, renewed every three months, serving as commendatory letters. Those deemed unworthy did not receive new tickets, ensuring the spiritual integrity of the societies.

The class-meeting system, formalized around 1742, originated from a practical need: when debt on a chapel became a burden, it was proposed that one in twelve members collect offerings regularly from the other eleven. These weekly meetings, led by a designated leader, focused on spiritual fellowship and guidance. Early on, there were also "bands" for the spiritually gifted who consciously pursued Christian perfection, and "select societies" for those believed to have achieved it (77 members in 1744). A category for "penitents" also existed for backsliders.

To maintain order and spiritual discipline within the societies, Wesley established a probationary system. He undertook regular "quarterly visitations" or conferences to each society. As the movement grew, he formalized a set of "General Rules" for the "United Societies" in 1743, which became the nucleus of the Methodist Discipline, still foundational to modern Methodism.

7.2. Itinerant Ministry and Lay Preaching

A key factor in the rapid growth of Methodism was Wesley's decision to authorize lay preachers. Recognizing that he and the few ordained clergy cooperating with him could not meet the overwhelming demand for preaching, Wesley began approving unordained men, as early as 1739, to preach and perform pastoral work. This expansion of lay preachers was revolutionary and crucial to Methodism's spread.

Wesley himself engaged in an extensive itinerant ministry, traveling widely, primarily on horseback, and preaching two or three times daily. Stephen Tomkins notes that Wesley "rode 250.00 K mile, gave away 30.00 K GBP, ... and preached more than 40,000 sermons." He traveled across Great Britain and Ireland, visiting Manchester at least fifteen times between 1733 and 1790, and Ireland annually from 1747 to 1789. His sermons, though sometimes difficult to understand, were delivered with such passion that they deeply moved his audiences. He continued this rigorous schedule for fifty years, preaching in churches when invited, and in fields, halls, cottages, and chapels when denied access to pulpits. The numbers of Methodists in Ireland alone grew to over 15,000 by 1795.

7.3. Chapels and Organizational Structure

As his societies grew, they required dedicated places of worship. Wesley began to provide chapels, starting with the New Room, Bristol in Bristol, followed by The Foundery and later Wesley's Chapel in London, and other locations. The Foundery, located in the Moorfields area of London, was a former brass gun and mortar foundry that had been vacant for 23 years after an explosion in 1716.

Initially, the Bristol chapel (built in 1739) was managed by trustees, but a large debt led Wesley's friends to urge him to take sole control, making him the sole trustee. This precedent was followed for all Methodist chapels, which were committed in trust to him until, by a "deed of declaration," all his interests were transferred to a body of preachers known as the "Legal Hundred."

Wesley laid the foundations for the modern organization of the Methodist Church. Over time, a complex structure emerged, including societies, "circuits" (groups of societies), quarterly meetings, annual conferences, classes, and bands. Traveling preachers were appointed to circuits for two-year periods. Circuit officials met quarterly under a senior traveling preacher or "assistant." Annual conferences, with Wesley as president, became the ruling body coordinating doctrine and discipline for the entire connection. In 1746, Wesley appointed "helpers" to specific circuits, each with at least 30 appointments a month, and established the "itinerancy" system, requiring preachers to move circuits every one or two years to promote efficiency.

In 1744, John and Charles Wesley, along with four other clergy and four lay preachers, held the first Methodist conference in London to discuss doctrinal and administrative matters. This conference became the governing body of the movement.

Wesley's relationship with Grace Murray, a class leader and housekeeper who nursed him during an illness in Newcastle in 1748, was significant. He proposed marriage to her in Ireland in 1749, but they never married. It is suggested that his brother Charles objected to the engagement, though this is disputed. Grace later married John Bennett, a preacher.

7.4. Ordination and Separation from the Church of England

As the Methodist societies multiplied, they began to adopt elements of an ecclesiastical system, widening the divide between Wesley and the Church of England. While some of his preachers and societies pushed for separation, his brother Charles strenuously opposed it. Wesley himself initially refused to leave the Church of England, believing that Anglicanism, "with all her blemishes, [...] [was] nearer the Scriptural plans than any other in Europe." In 1745, he stated he would make any concession his conscience permitted to live in peace with the clergy, but he would not abandon the doctrine of inward salvation by faith, nor stop preaching, dissolve the societies, or end lay preaching. He also believed it was wrong to administer sacraments without episcopal ordination.

However, Wesley's views evolved. In 1746, after reading Lord King's account of the primitive church, he became convinced that apostolic succession could be transmitted not only through bishops but also through presbyters (priests). He declared himself "a scriptural episkopos as much as many men in England," though he also called the idea of uninterrupted succession a "fable." Later, Edward Stillingfleet's Irenicon further led him to conclude that ordination could be valid when performed by a presbyter. Some scholars even suggest that Wesley was secretly consecrated a bishop in 1763 by Erasmus of Arcadia, a Greek Orthodox bishop, but could not openly announce it due to the Præmunire Act.

The American Revolutionary War significantly impacted the situation. After the American War of Independence, the Church of England was disestablished in the United States, leaving American Methodists without sacraments or episcopal oversight, as the Church of England had not yet appointed a bishop for the nascent Protestant Episcopal Church in America. In 1784, Wesley felt he could no longer wait for the Bishop of London to act. He controversially ordained Thomas Coke as a superintendent for Methodists in the United States by the laying on of hands, despite Coke already being an Anglican priest. He also ordained Richard Whatcoat and Thomas Vasey as presbyters, who sailed to America with Coke. Wesley intended for Coke and Francis Asbury (whom Coke ordained as superintendent by Wesley's direction) to ordain others in the newly formed Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States. In 1787, Coke and Asbury persuaded American Methodists to refer to them as "bishops" rather than "superintendents," overriding Wesley's objections to the change.

Charles Wesley was alarmed by these ordinations, begging John to stop before he "quite broken down the bridge" and not "leave an indelible blot on our memory." John replied that he had not separated from the church nor intended to, but he must save as many souls as he could while alive, "without being careful about what may possibly be when I die." Although he rejoiced in the freedom of American Methodists, he continued to advise his English followers to remain within the established church, and he himself died within it. However, after his death, the British Methodist movement did eventually separate from the Church of England, following the precedent set in America.

8. Theological Contributions

John Wesley's theological ideas were systematic and profoundly influenced Christian thought, particularly within Methodism, laying the groundwork for Wesleyan theology.

8.1. Theological Methodology (Wesleyan Quadrilateral)

The 20th-century Wesleyan scholar Albert Outler argued that Wesley developed his theology using a method Outler termed the Wesleyan Quadrilateral. This approach emphasizes the interplay of four sources of doctrine: Scripture, Tradition, Reason, and Experience.

Wesley believed that the living core of Christianity was contained in Scripture (the Bible), which served as the sole foundational source of theological development. He called himself "a man of one book," despite being exceptionally well-read for his era, highlighting the centrality of the Bible. However, he also believed that doctrine must align with Christian orthodox tradition, making tradition the second aspect of the Quadrilateral. Wesley contended that theological method also involved experiential faith, meaning that truth would be vivified in the collective personal experience of Christians. Finally, every doctrine had to be rationally defensible, as Wesley did not separate faith from reason. He argued that Tradition, Experience, and Reason were always subject to Scripture, because only there is the Word of God revealed "so far as it is necessary for our salvation."

8.2. Key Doctrines

The doctrines Wesley emphasized in his sermons and writings include prevenient grace, present personal salvation by faith, the witness of the Spirit, and entire sanctification.

- Prevenient Grace:** This theological underpinning of his belief asserted that all persons are capable of being saved by faith in Christ. Wesley rejected the Calvinist understanding of predestination (that some are elected for salvation and others for damnation), instead emphasizing humanity's utter dependence on God's grace. He taught that God's grace is always at work, spiritually enabling all people to respond to faith and empowering them with actual freedom to respond to God through their individual experiences.

- Salvation by Faith:** Wesley emphasized that salvation is a personal experience, received by faith alone. This was a core tenet of his Aldersgate experience.

- Witness of the Spirit:** Wesley defined the witness of the Spirit as "an inward impression on the soul of believers, whereby the Spirit of God directly testifies to their spirit that they are the children of God." He rooted this doctrine in biblical passages like Romans 8:16 and saw it as closely related to his belief in personal salvation; each individual must ultimately believe the Good News for themselves.

- Entire Sanctification (Christian Perfection):** Wesley described this in 1790 as the "grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called 'Methodists'," stating that its propagation was the reason Methodists came into existence. He taught that entire sanctification was obtainable after justification by faith, occurring between justification and physical death. He defined it as:

"That habitual disposition of soul which, in the sacred writings, is termed holiness; and which directly implies, the being cleansed from sin, 'from all filthiness both of flesh and spirit;' and, by consequence, the being endued with those virtues which were in Christ Jesus; the being so 'renewed in the image of our mind,' as to be 'perfect as our Father in heaven is perfect."

Wesley avoided the term "sinless perfection" due to its ambiguity, preferring "perfect in love." This meant that a believer's motives would be guided by a deep desire to please God, rather than being self-centered, enabling them to refrain from what Wesley called "sin rightly so-called" (conscious or intentional breach of God's will). Secondly, to be made perfect in love meant living with a primary regard for others and their welfare, based on Christ's command to "love your neighbour as you love yourself." This orientation, combined with love for God, would constitute "a fulfilment of the law of Christ." Wesley viewed perfection as a "second blessing" and an instantaneous sanctifying experience, asserting that individuals could have the assurance of their entire sanctification through the testimony of the Holy Spirit. He collected and published testimonies of those who claimed to have achieved this state, though he admitted he himself had not. Wesley's study of Eastern Orthodoxy particularly influenced his embrace of the doctrine of Theosis.

8.3. Arminianism vs. Calvinism

Wesley engaged in significant theological controversies as he sought to expand church practice, most notably his debates with Calvinism. His father was of the Arminian school, and Wesley independently arrived at strong conclusions against the Calvinistic doctrines of election and reprobation during his college years. His system of thought became known as Wesleyan Arminianism, further developed by his fellow preacher John William Fletcher. While Wesley knew little about Jacob Arminius's specific beliefs, he later acknowledged general agreement with Arminius, becoming perhaps the clearest English proponent of Arminianism.

Wesley's belief in prevenient grace was the theological underpinning for his conviction that all persons could be saved by faith in Christ. He rejected the Calvinist understanding of predestination, which he considered blasphemous, stating it represented "God as worse than the devil." He emphasized humanity's complete dependence on God's grace, which he believed was universally at work to enable all people to come to faith.

In contrast, George Whitefield inclined towards Calvinism, embracing the views of the New England School of Calvinism during his first tour in America. When Wesley preached his sermon Freedom of Grace in 1739, attacking the Calvinistic understanding of predestination, Whitefield asked him not to repeat or publish it to avoid dispute. Wesley published it nonetheless, leading to responses from Whitefield and others. The two men separated their practices in 1741, with Wesley noting that those who held to unlimited atonement did not desire separation, but "those who held 'particular redemption' would not hear of any accommodation."

Whitefield, Howell Harris (leader of the Welsh Methodist revival), John Cennick, and others became founders of Calvinistic Methodism. Despite their theological differences, Whitefield and Wesley soon reconciled and maintained an unbroken friendship, though they traveled different paths. When asked if he expected to see Wesley in heaven, Whitefield famously replied, "I fear not, for he will be so near the eternal throne and we at such a distance, we shall hardly get sight of him."

The controversy reignited in 1770 with violence and bitterness, as views of God intertwined with views of human potential. Augustus Toplady, Daniel Rowland, and Sir Richard Hill championed the Calvinist side, while Wesley and Fletcher defended Arminianism. Toplady edited The Gospel Magazine, which covered the dispute. In 1778, Wesley launched The Arminian Magazine not to convert Calvinists, but to preserve Methodists, teaching the truth that "God willeth all men to be saved" as the only way to secure "lasting peace." Some scholars have suggested that later in life, Wesley may have embraced the doctrine of universal salvation, citing his 1787 endorsement of a work by Charles Bonnet that concluded in favor of universalism, though this interpretation is disputed.

9. Social Advocacy and Reform

John Wesley's engagement with the social issues of his time and his efforts towards reform reflect a profound commitment to social justice, driven by his theological convictions. He believed that Christian faith must manifest in outward holiness and active compassion for the marginalized.

9.1. Abolitionism

Later in his ministry, Wesley became a fervent abolitionist, speaking out and writing forcefully against the slave trade. He denounced slavery as "the sum of all villainies" and meticulously detailed its abuses. In 1774, he published a polemical tract titled Thoughts Upon Slavery, asserting, "Liberty is the right of every human creature, as soon as he breathes the vital air; and no human law can deprive him of that right which he derives from the law of nature." He viewed both the selling and buying of slaves as acts of "wolves" and believed it was a Christian's duty to proclaim God's liberation and oppose slavery.

Wesley's abolitionist message had a significant impact. He influenced George Whitefield to travel to the American colonies, sparking transatlantic debates on slavery. He also mentored William Wilberforce, a key figure in the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Furthermore, Wesley's message contributed to the conversion of a young African American named Richard Allen in 1777, who later founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in 1816, a prominent denomination in the Methodist tradition.

9.2. Prison Reform and Social Welfare

Wesley's commitment to social justice extended to improving prison conditions and advocating for the poor. He and the Holy Club began regularly visiting prisoners in 1730, preaching, educating, and providing relief, even paying debts for jailed individuals to secure their release. This early work laid the foundation for his lifelong concern for the incarcerated.

He also held strong views on economic justice, arguing that the industrial economic system, a consequence of the Industrial Revolution, had created immense social inequality. He challenged the notion that the poor were simply lazy, asserting that the system prioritized tools and livestock over human beings, leading to widespread crime and ignorance. To address these issues, Wesley initiated practical measures: he established schools for poor children, provided housing for widows, created lending institutions to free people from usurers, and wrote books on simple medicine. His sermon The Use of Money outlined his economic philosophy: "gain all you can, save all you can, and give all you can," emphasizing productivity, frugality, and charitable giving. He believed that wealth should be used to alleviate poverty and promote the common good.

9.3. Support for Women Preachers

Wesley's views on women's roles in ministry evolved, leading to his eventual support for women preachers, recognizing their significant contributions to the Methodist movement. Women were actively encouraged to lead classes within Methodist societies. In 1761, he informally permitted Sarah Crosby, one of his converts and a class leader, to preach when she found herself addressing over 200 people in a class meeting. Crosby wrote to Wesley seeking his advice and forgiveness, and he allowed her to continue, advising her to refrain from as many preaching mannerisms as possible. Between 1761 and 1771, Wesley provided detailed instructions to Crosby and others on acceptable preaching styles, for instance, allowing Crosby to give exhortations in 1769.

In the summer of 1771, Mary Bosanquet wrote to Wesley defending her and Sarah Crosby's preaching and class leadership at her orphanage, Cross Hall. Bosanquet's letter is considered the first comprehensive defense of women's preaching in Methodism, arguing that women should be permitted to preach when they experienced an "extraordinary call" or divine permission. Wesley accepted Bosanquet's argument and formally began to allow women to preach in Methodism in 1771. Methodist women, including preachers, continued to observe the ancient practice of Christian head covering.

9.4. Interfaith Relations and Views

Wesley generally assumed the superiority of Christianity based on his commitment to biblical revelation as "the book of God." His theological interpretation of Christianity sought its imperative rather than considering other Abrahamic religions and Eastern religions to be equal. He often regarded the lifestyles of Muslims as an "ox goad" to prick the collective Christian conscience. While his Letter to a Roman Catholic (1749) is sometimes seen as an act of religious tolerance, appealing for understanding and shared Christian faith, Wesley remained deeply rooted in the anti-Catholicism characteristic of 18th-century England.

10. Personal Life and Literary Work

John Wesley's personal life was characterized by rigorous discipline, extensive travel, and prolific literary output, all intertwined with his commitment to the Methodist movement.

10.1. Marriage and Personal Relationships

Despite favoring celibacy over marriage, Wesley married unhappily in 1751, at the age of 48, to Mary Vazeille. Mary was a well-to-do widow and mother of four children. The couple had no children of their own, and their marriage was deeply unhappy. John Singleton notes that Mary, known as Molly, "By 1758 she had left him-unable to cope, it is said, with the competition for his time and devotion presented by the ever-burgeoning Methodist movement. Molly, as she was known, was to return and leave him again on several occasions before their final separation." Wesley wryly recorded in his journal, "I did not forsake her, I did not dismiss her, I will not recall her." Mary Vazeille left Wesley permanently fifteen years later.

In 1770, upon the death of George Whitefield, Wesley wrote a memorial sermon praising Whitefield's admirable qualities and acknowledging their theological differences. He stated, "There are many doctrines of a less essential nature ... In these we may think and let think; we may 'agree to disagree.' But, meantime, let us hold fast the essentials..." Wesley may have been the first to use "agree to disagree" in print in its modern sense of tolerating differences, though he attributed the saying to Whitefield.

Wesley experienced a grave illness during a visit to Lisburn, Ireland, in June 1775, but recovered while staying at the home of Henrietta Gayer, a leading Methodist.

10.2. Health, Diet, and Habits

Wesley maintained a remarkably disciplined lifestyle. He practiced a vegetarian diet and, in later life, abstained from wine for health reasons. He claimed, "thanks be to God, since the time I gave up flesh meals and wine I have been delivered from all physical ills." While he warned against the dangers of alcohol abuse in his famous sermon, The Use of Money, and in a letter to an alcoholic, his statements primarily concerned "hard liquors and spirits" rather than low-alcohol beer, which was often safer than contaminated water at the time. He even encouraged experiments related to the role of hops in beer making in a 1789 letter. Nevertheless, Methodist churches became pioneers in the teetotal temperance movement of the 19th and 20th centuries, with abstinence becoming de rigueur in British Methodism.

Wesley was described as "rather under the medium height, well proportioned, strong, with a bright eye, a clear complexion, and a saintly, intellectual face." He typically woke at 4:00 AM and meticulously managed his time, avoiding idleness. He was an admirer of music, particularly Charles Avison. After attending a performance of Mr. Handel's Messiah at Bristol Cathedral in 1758, he noted in his journal, "I doubt if that congregation was ever so serious at a sermon as they were during this performance. In many places, especially several of the choruses, it exceeded my expectation."

He was also an early proponent of electric shock for treating illnesses, even administering it himself to followers and prisoners. He superintended orphanages and schools, including Kingswood School.

10.3. Literary Output

Wesley was a prolific writer, editor, and abridger, producing some 400 publications. His writings covered theology, music, marriage, medicine, abolitionism, and politics. He was known for his logical thinking and expressed himself clearly, concisely, and forcefully. His written sermons were characterized by simplicity and earnestness, being doctrinal but not dogmatic.

Between 1746 and 1760, Wesley compiled several volumes of written sermons, published as Sermons on Several Occasions; the first four volumes comprise forty-four sermons that are doctrinal in content. His Forty-Four Sermons and the Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament (1755) are considered Methodist doctrinal standards. While he often preached spontaneously and briefly, he was capable of great length and power in his delivery.

In his Christian Library (1750), Wesley included writings by mystics such as Macarius of Egypt, Ephrem the Syrian, Madame Guyon, François Fénelon, Ignatius of Loyola, John of Ávila, Francis de Sales, Blaise Pascal, and Antoinette Bourignon. This work reflects the influence of Christian mysticism throughout Wesley's ministry, although he generally rejected it after his unsuccessful mission in Georgia.

Wesley's prose Works were first collected by himself in 32 volumes (Bristol, 1771-1774). His chief prose works are a standard publication in seven octavo volumes by the Methodist Book Concern, New York. The Poetical Works of John and Charles, edited by G. Osborn, appeared in 13 volumes (London, 1868-1872).

Other notable works include his Journals (originally published in 20 parts, London, 1740-1789), which offer invaluable insights into his life and travels; The Doctrine of Original Sin (Bristol, 1757), a reply to John Taylor of Norwich; An Earnest Appeal to Men of Reason and Religion (2nd ed., Bristol, 1743), a detailed defense of Methodism that described the societal and ecclesiastical evils of his time; and A Plain Account of Christian Perfection (1766).

Wesley also adapted the Book of Common Prayer for use by American Methodists in his Sunday Service. In his Watchnight service, he incorporated a pietist prayer now widely known as the Wesley Covenant Prayer, perhaps his most famous contribution to Christian liturgy. He was also a noted hymn-writer, translator, and compiler of a hymnal.

Beyond theology, Wesley wrote on physics and medicine, including The Desideratum, subtitled Electricity made Plain and Useful by a Lover of Mankind and of Common Sense (1759), and Primitive Physic, Or, An Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases (1744). Despite his prolific output, Wesley faced accusations of plagiarism for borrowing heavily from an essay by Samuel Johnson published in March 1775. He initially denied the charge but later issued an official apology.

11. Death and Legacy

John Wesley's final years saw a decline in his health, but his profound impact on religious and social history continued to grow, leaving an enduring legacy that shaped Methodism and beyond.

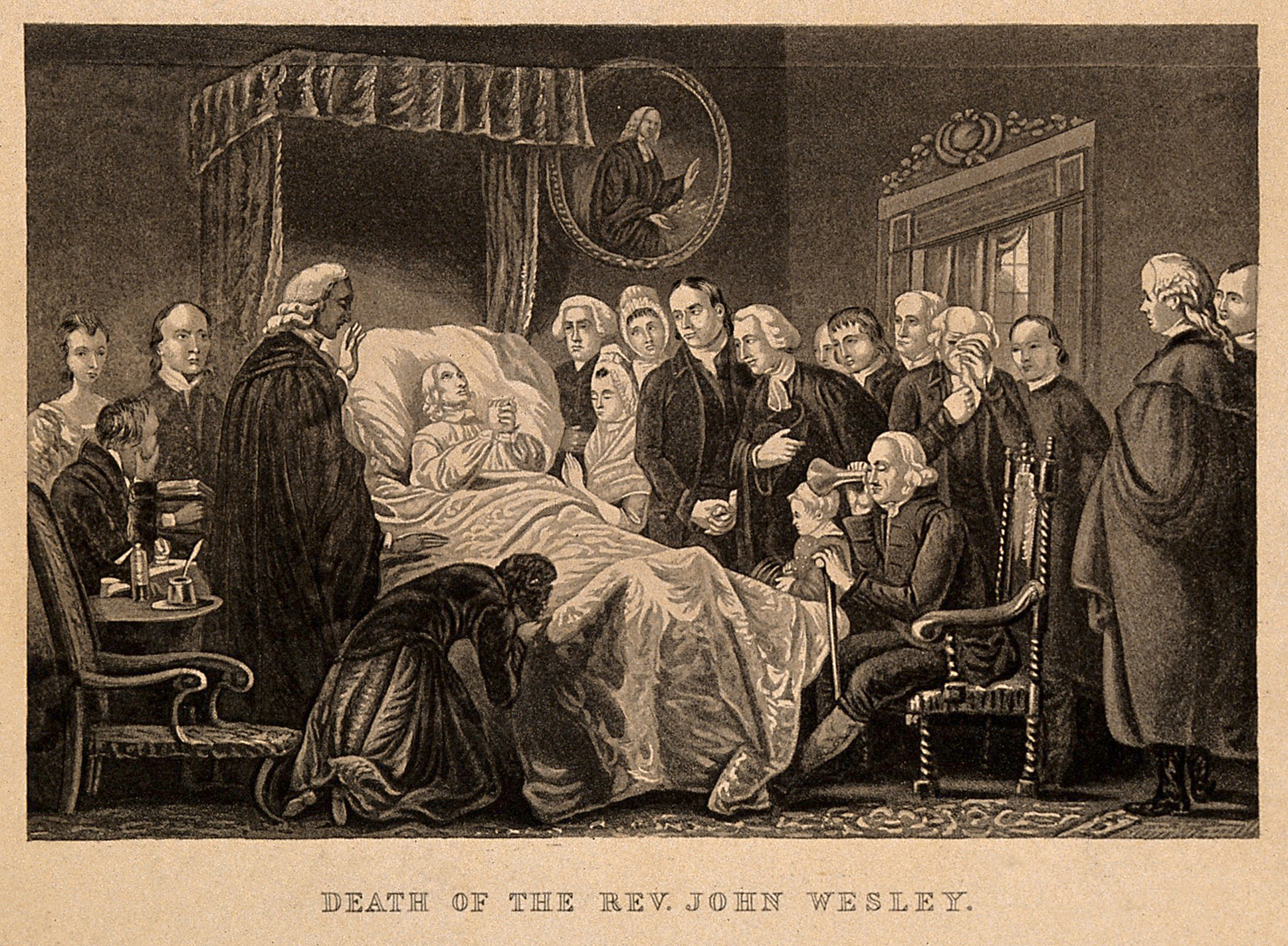

11.1. Final Years and Death

Wesley's health sharply declined towards the end of his life, leading him to cease preaching. On June 28, 1790, less than a year before his death, he wrote:

This day I enter into my eighty-eighth year. For above eighty-six years, I found none of the infirmities of old age: my eyes did not wax dim, neither was my natural strength abated. But last August, I found almost a sudden change. My eyes were so dim that no glasses would help me. My strength likewise now quite forsook me and probably will not return in this world.

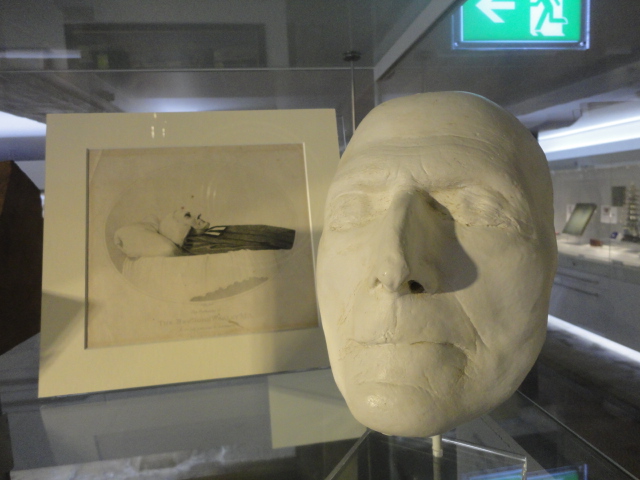

Wesley was cared for during his final months by Elizabeth Ritchie and his physician John Whitehead. He died peacefully on March 2, 1791, at the age of 87, in London. As he lay dying, his friends gathered around him. Wesley grasped their hands, repeatedly saying, "Farewell, farewell." In his final moments, he declared, "The best of all is, God is with us," lifting his arms and repeating the words in a feeble voice. He was entombed at his chapel on City Road, London. Elizabeth Ritchie wrote an account of his death, which was quoted by Whitehead at his funeral.

Due to his charitable nature and extensive giving, Wesley died poor, leaving behind a "good library of books, a well-worn clergyman's gown," and the burgeoning Methodist Church. At the time of his death, the Methodist movement comprised 135,000 members and 541 itinerant preachers.

11.2. Theological and Social Influence

Wesley remains the primary theological influence on Methodists and Methodist-heritage groups worldwide, with the movement numbering 75 million adherents in over 130 countries. His teachings, particularly Wesleyan theology, serve as a foundational basis for the Holiness movement, which includes denominations like the Free Methodist Church, the Church of the Nazarene, and The Salvation Army. Pentecostalism and parts of the Charismatic movement are also offshoots of the Holiness movement, tracing their roots back to Wesleyan thought.

Wesley's call to personal and social holiness continues to challenge Christians globally, inspiring efforts to participate in the Kingdom of God through both spiritual transformation and social action. He is also credited with refining Arminianism by integrating a strong evangelical emphasis on the Reformed doctrine of justification by faith. His evangelical movement, which injected new spiritual vitality into the Church of England, also influenced its development into the modern Anglican Communion, particularly through the balance between its High Church traditions and the evangelical fervor he championed. This blend of tradition, liturgy, and personal spiritual experience is a hallmark of his lasting impact.

11.3. Commemorations and Memorials

John Wesley is commemorated in various Christian calendars:

- In the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on March 2, alongside his brother Charles.

- The Wesley brothers are honored with a Lesser Feast on March 3 in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church.

- He is commemorated on May 24 (Aldersgate Day) with a Lesser Festival in the Church of England's Calendar.

In 2002, Wesley was listed at number 50 on the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons, based on a public poll. While initially barred from preaching in many parish churches and facing persecution, he later became widely respected and was described by the end of his life as "the best-loved man in England."

Wesley's house and chapel, which he built in 1778 on City Road in London, remain intact today. The chapel hosts a thriving congregation with regular services, and the Museum of Methodism is located in its crypt. Numerous schools, colleges, hospitals, and other institutions are named after Wesley, and many others bear the name of Methodism. In 1831, Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, became the first institution of higher education in the United States to be named after Wesley. Originally an all-male Methodist college, it is now a secular institution. Approximately 20 other unrelated colleges and universities in the United States also bear his name. His legacy is also preserved in Kingswood School, which he founded in 1748 for the education of Methodist preachers' children. One of the four boarding houses at St Marylebone Church of England School in London is also named after John Wesley.

A replica of the rectory where Wesley lived as a boy was built in the 1990s at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina. This was part of a complex of buildings for the World Methodist Council, which included a museum housing Wesley's letters and a pulpit he used. However, this museum faced difficulties and closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with its contents transferred to Bridwell Library of Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas.

Wesley's life and work have also been depicted in film and musical theatre:

- In 1954, the Radio and Film Commission of the Methodist Church of Great Britain, in cooperation with J. Arthur Rank, produced the film John Wesley, a live-action retelling starring Leonard Sachs.

- In 2009, a more ambitious feature film, Wesley, was released by Foundery Pictures, starring Burgess Jenkins as Wesley, June Lockhart as Susanna Wesley, R. Keith Harris as Charles Wesley, and Kevin McCarthy as Bishop Ryder. The film was directed by John Jackman.

- In 1976, the musical Ride! Ride!, composed by Penelope Thwaites and written by Alan Thornhill, premiered at the Westminster Theatre in London's West End. Based on the true story of Martha Thompson's incarceration in Bedlam, the musical ran for 76 performances and has since had over 40 productions.