1. Overview

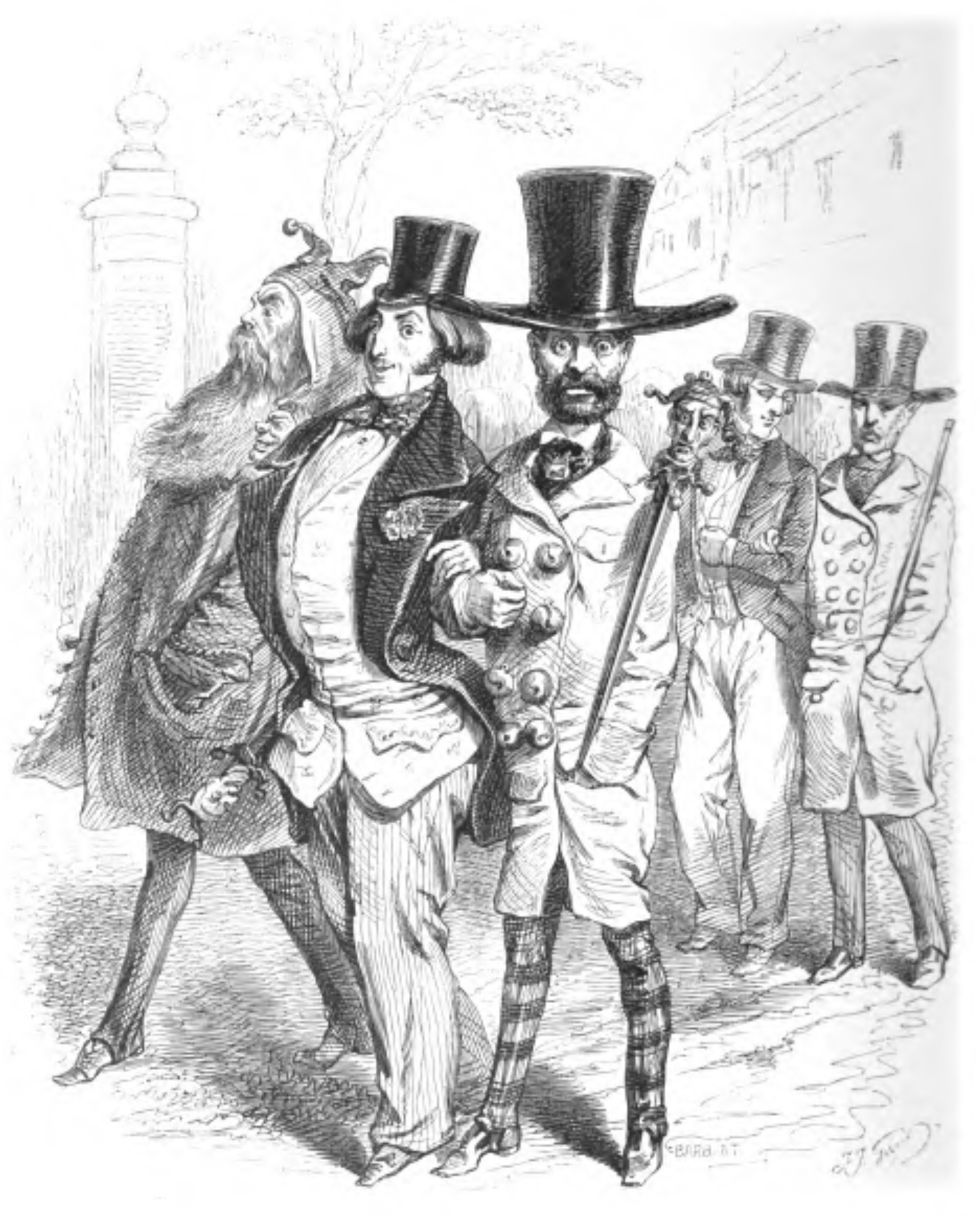

Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard (September 13, 1803 - March 17, 1847), widely known by his pseudonym Grandville, was a highly influential and prolific French illustrator and caricaturist. He is often recognized as "the first star of French caricature's great age" and a "proto-surrealist" whose work deeply influenced later artistic movements like Surrealism, Dada, and Pop Art, as well as prominent artists like John Tenniel, Gustave Doré, Félicien Rops, and even Walt Disney.

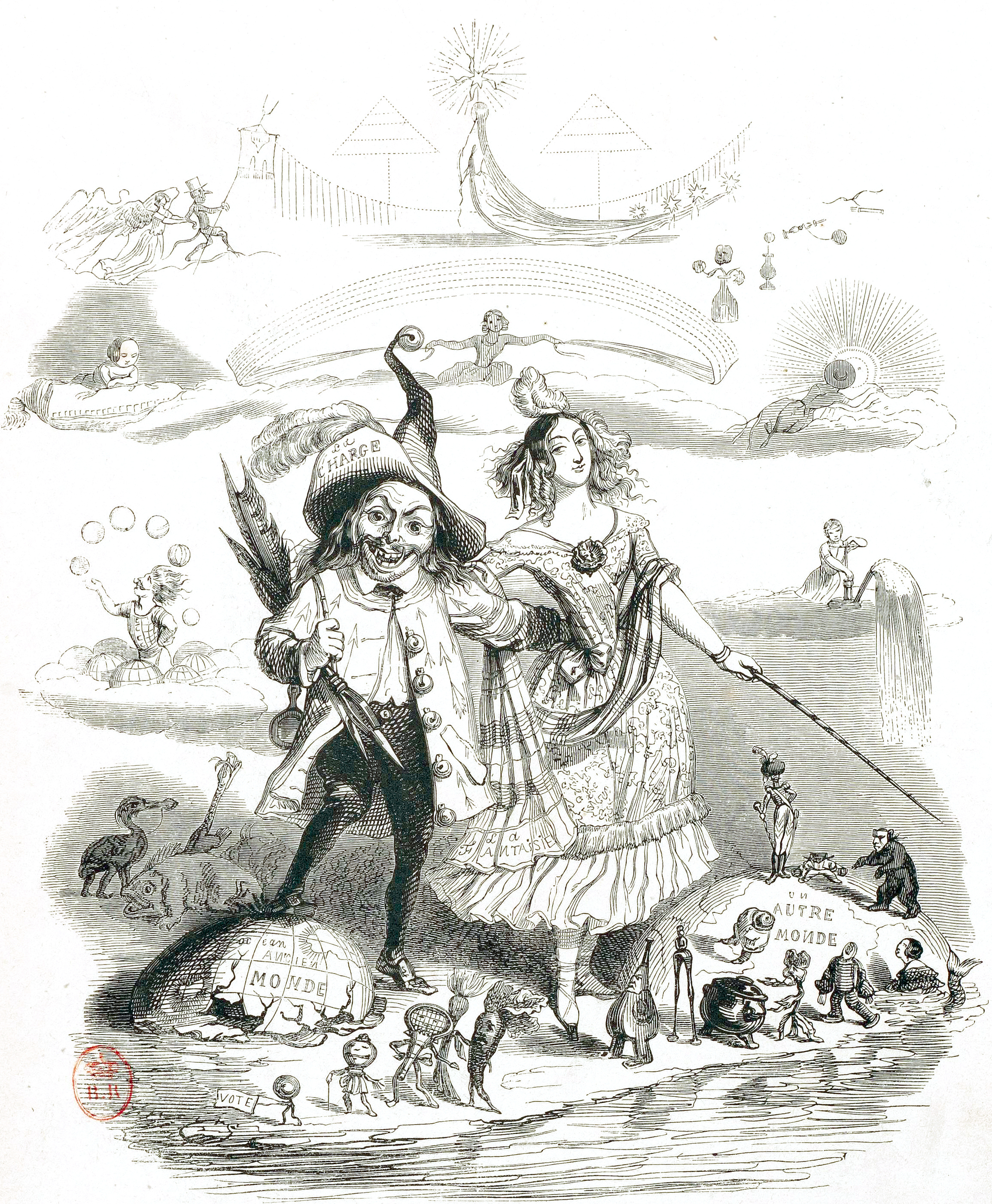

Grandville's illustrations are characterized by elements that are symbolic, dreamlike, and incongruous, frequently featuring anthropomorphic figures with human bodies and animal heads, and zoomorphic elements. His art often retained a sharp sense of social commentary, making him a significant figure in political satire following the July Revolution of 1830. He actively participated in the turbulent political climate, producing provocative cartoons that criticized the monarchy and faced severe censorship and persecution. After stringent censorship laws were enacted in 1835, Grandville shifted his focus to book illustration, contributing to numerous classic literary works and creating his own image-centric books such as Un autre monde (1844) and Les fleurs animées (1846). Despite personal tragedies and historical misconceptions about his mental state, his artistic output remained profound and imaginative until his death at a relatively young age. His legacy extends to popular culture, with his artwork inspiring musical acts like Queen and Alice in Chains, and even modern video games.

2. Life

Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard's life was marked by both significant artistic achievements and profound personal challenges, culminating in a pivot from political satire to imaginative book illustration.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard was born on September 13, 1803, in Nancy, Meurthe-et-Moselle, in northeastern France. His parents, Jean-Baptiste Gérard, a noted painter of miniatures, and Catherine-Émilie Viaud, named him Adolphe, after an older brother who had died three months before his birth, a name he carried throughout his life. Grandville inherited his father's artistic talent, showing an aptitude for drawing from an early age. He received his initial art education from his father, whose influence on his draftsmanship and dense compositions remained evident even in his mature work.

Around 1823-1825, after completing his schooling, Grandville moved to Paris to pursue a career in illustration and lithography. He was encouraged by Léon-André Larue, a relative who was also a miniature painter and lithographer. Lithography, a relatively new invention from Germany in the 1790s, was rapidly gaining popularity in Paris as a fast and inexpensive alternative to traditional engraving and etching for mass-producing prints and illustrated publications. This period of social and political upheaval saw the rise of inexpensive illustrated newspapers, creating numerous opportunities for draftsmen and illustrators in Parisian publishing and lithography studios. Grandville was drawn to and influenced by the growing popularity of satirical, often political, prints, caricatures, and illustrations in France. His first lithograph, La Marchande de cerises (The Cherry Seller), was published in Nancy in 1824 or 1825.

Grandville's parents had friends and family in Paris's theater scene, including his relative Frédéric Lemétheyer, a stage manager at the Opéra-Comique, who provided early work and connections. It was in Paris that he began using his well-known pseudonym, "Grandville," derived from "Gérard de Grandville," the stage name of his paternal grandparents when they were actors in the court of Lorraine. Throughout his career, this pseudonym appeared in various forms, including Jean-Jacques Grandville, J. J. Grandville, Jean Ignace Isidore Grandville, J. I. I. Grandville, and Jean de Granville.

During the late 1820s and early 1830s, Grandville lived a bohemian life, occupying a small, pen-and-paper-crowded room that became a gathering place for artists, writers, singers, and lithographers. Among his acquaintances were the painter Paul Delaroche and the writer Alexandre Dumas, who recalled the period as one of camaraderie, marked by smoking, joking, and arguing, regardless of financial means. Grandville was described as thin, somewhat quiet, and at times melancholy, yet Dumas noted his sharp wit and competitive spirit. It was during this time that he met Charles Philipon, the charismatic 28-year-old editor and lithographer for the newspaper La Silhouette.

2.2. Early Career and Rise to Fame

Grandville's professional activities commenced with illustrations for playing card decks and collaboration with Hippolyte Lecomte, a Parisian painter and ballet set designer. For Lecomte, he produced a set of color lithographs titled Costumes De ThéãterFrench in 1826. This was followed by other series, including 12 lithographs created for the printer Langlumé, titled Les Dimanches d'un bourgeois de Paris ou Les tribulations de la petite propriétéFrench (Sundays of a Paris Bourgeois or The Tribulations of Small Property), also in 1826. Subsequent collections included 53 prints in La Sibylle des salonsFrench (The Sibyl of the Salons) in 1827 and 12 prints in Titres pour morceaux de musiqueFrench (Titles for Musical Pieces) in 1828.

His first significant success came with Les Métamorphoses du jour (The Metamorphoses of the Day), a collection of 70 color lithographs published in 1829. In this series, Grandville depicted figures with human bodies and the heads of various animals, from fish to elephants, acting out a human comedy that perceptively satirized the Parisian bourgeoisie and human nature. This work firmly established his reputation with the public, leading to increased demand for his services from publishers and periodicals.

In 1830, he published Voyage pour l'éternitéFrench (Voyage to Eternity), a series of nine lithographs featuring Death, in various skeletal forms, visiting Parisians and triumphantly leading young soldiers to their demise. Due to its dark theme, possibly inspired by Thomas Rowlandson's Dance of Death, printing ceased after only a few copies were made. Despite its limited circulation, it garnered him further notoriety and the admiration of figures such as Champfleury and Honoré de Balzac.

2.3. Political Satire and Censorship

Following the French Revolution of 1830, also known as the "Three Glorious Days" (July 27-29), in which the liberal, republican working class of Paris overthrew the Bourbon monarch Charles X in favor of Louis Philippe I, Grandville's artistic direction became deeply intertwined with political satire. However, the republican workers who had been pivotal in bringing Louis Philippe to power were quickly marginalized as the bourgeoisie consolidated the social, economic, and political gains of the revolution for their own benefit. Alexandre Dumas participated in the street fighting, and it is plausible that Grandville and his associates were also involved. This period saw the emergence of numerous satirical republican periodicals in Paris, including La Silhouette, Tribune, La Caricature, L'Artiste, Le Charivari, Corsaire, Réformateur, Bon Sens, and Populaire. These papers were often provocative and political, highlighting the new monarchy's dismissal of the workers who had facilitated its rise.

Grandville's success with his earlier lithographic series led to invitations to design cartoons for these publications. His first such collaboration was with La Silhouette, where his friend Charles Philipon served as editor. In June 1830, Grandville's lithograph Let's Put Out the Light and Rekindle the Fire!, which criticized press censorship by contrasting the "light" of the Enlightenment with the "fire" of book-burning, was published but quickly proscribed by the government. La Silhouette had a short run from December 1829 to January 1831, ultimately folding under government fines and pressure. It was one of several similar publications that succumbed to state pressure, often seeing the same editors, writers, and illustrators moving between papers.

Before La Silhouette ceased publication, Charles Philipon and Auguste Audibert founded La Caricature in 1830, with Honoré de Balzac as a literary editor and Grandville, Achille Devéria, Honoré Daumier, and others as cartoonists and lithographers. From 1830 to 1835, Philipon and La Caricature waged an aggressive campaign against Louis-Philippe's regime. Grandville contributed numerous prints to this "war," including multi-part lithographs published over several weeks, which collectors could assemble, such as the seven-part Grande Croisade contre la LibertéFrench (The Great Crusade Against Liberty) and La Chasse à la LibertéFrench (The Hunters in Pursuit of Liberty). These attacks on the monarchy were taken seriously and led to severe consequences. Louis Philippe's government seized papers, levied hefty fines, and imprisoned editors, writers, and illustrators. Daumier, for instance, was fined 500 FRF and incarcerated for six months in 1832. Philipon faced even larger fines and longer prison sentences, as did other publishers. Grandville himself endured persistent police harassment, including searches, and one incident described as a mugging by thuggish policemen in his own building, thwarted by a neighbor with pistols. These events are said to have deeply distressed him. Grandville filed criminal charges for forced entry into his residence and later published the lithograph Oh!! Les vilaines mouches!! (Oh!! These nasty flies!!). To help pay the papers' fines, Philipon organized L'Association Mensuelle lithographique in the early 1830s, offering fine prints to its members, with Grandville producing over half of them.

As La Caricature faced collapse, Philipon launched another review, Le Charivari, in 1832. In Le Charivari, political attacks became more subtle, oblique, and veiled, often addressing broader, less overtly political social satire. Grandville, Philipon, and Daumier achieved a considerable level of celebrity among parts of the public, recognized as much for their defiant opposition as for their cartoons. Grandville's political cartoons were highly popular and respected. Publishers and editors, such as Édouard Charton of Le magasin pittoresque, afforded Grandville the freedom to choose his own subjects and create his images.

The business of caricaturing was financially precarious, with cartoonists typically paid per print. Artists considered themselves fortunate to secure regular drawing contracts. While Grandville initially produced his own lithographs, after 1831, for periodicals, he usually submitted original drawings to publishers, who then employed professional lithographers to copy his images for printing. Color was sometimes added by hand in colorist studios, typically by women who applied watercolor or gouache following the artists' notes.

On July 28, 1835, the fifth anniversary of the July Revolution, the "Fieschi attentat"-an unsuccessful assassination attempt on King Louis Philippe-occurred. This event quickly led to the implementation of the September Laws, which severely tightened press censorship, requiring government approval for caricatures before publication and forbidding the press from reporting on trials involving journalists. These laws also introduced significantly longer prison sentences for publishing criticisms of the king and his administration.

2.4. Transition to Book Illustration and Personal Life

The September Laws of 1835 marked a turning point in Grandville's career. At the outbreak of the July Revolution in 1830, he was a 26-year-old bachelor living a bohemian life. By 1835, he was 31, married, and a father. He ceased producing political cartoons after the new laws, turning his focus entirely to book illustration. It has been suggested that he found relief in leaving behind the political turmoil and police harassment.

In July 1833, Grandville married his cousin, Marguerite Henriette Fischer, from Nancy. The couple maintained an apartment near his studio and also rented a house on the outskirts of Paris. Their first son, Ferdinand, was born in 1834. A second son, Henri, was born in the fall of 1838. However, tragedy soon struck the family: Marguerite's health reportedly declined with each birth, and Ferdinand died of meningitis around the time Henri was born. In 1841, Henri tragically choked to death on a piece of bread while his parents watched helplessly. A third son, Georges, was born in July 1842, but Marguerite herself died of peritonitis later that same month. Grandville remarried in October 1843 to Catherine Marceline Lhuillier (1819-1888), with whom he had his fourth son, Armand, in 1845. One account states that his first wife, Marguerite, had a hand in selecting Catherine as a second wife and stepmother for her husband and son from her deathbed.

Grandville's first major undertaking in book illustration was a volume of song lyrics by the popular French songwriter Pierre-Jean de Béranger, initially published with 38 wood engravings in 1835, and an expanded edition featuring 100 engravings in 1837. This was followed by illustrations for several volumes of classic literature, including La Fontaine's Fables, Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, Swift's Gulliver's Travels, Boccaccio's The Decameron, and Cervantes's Don Quixote. While his illustrations for classic prose were often fine, they were largely conventional and did not allow him to fully unleash his imagination. He demonstrated a greater affinity for children's literature, visible in his illustrations for La Fontaine Fables, and later the Fables of Lavalette and Florian, which are considered among his finest works. He also created a series of drawings for Perrault's Little Red Riding Hood, though these remained unpublished.

Grandville skillfully adapted and refined his style when transitioning from political cartoons to book illustrations, a shift that coincided with evolving printing technologies, specifically from lithography to wood engraving. Previously, illustrations were often printed on separate pages inserted into the text. However, with end-cut wood engravings, fine details could be achieved on hard wooden blocks, allowing them to be placed alongside typographical blocks and printed on the same page as the text. This innovation reduced costs and improved the speed and quality of illustrated texts. Wood engravings also showed less deterioration than the metal plates used for intaglio printing. Grandville himself did not engrave the wooden blocks; typically, like other 19th-century illustrators, he provided his original drawings to publishers, who then employed professional engravers to carve the images for his book illustrations.

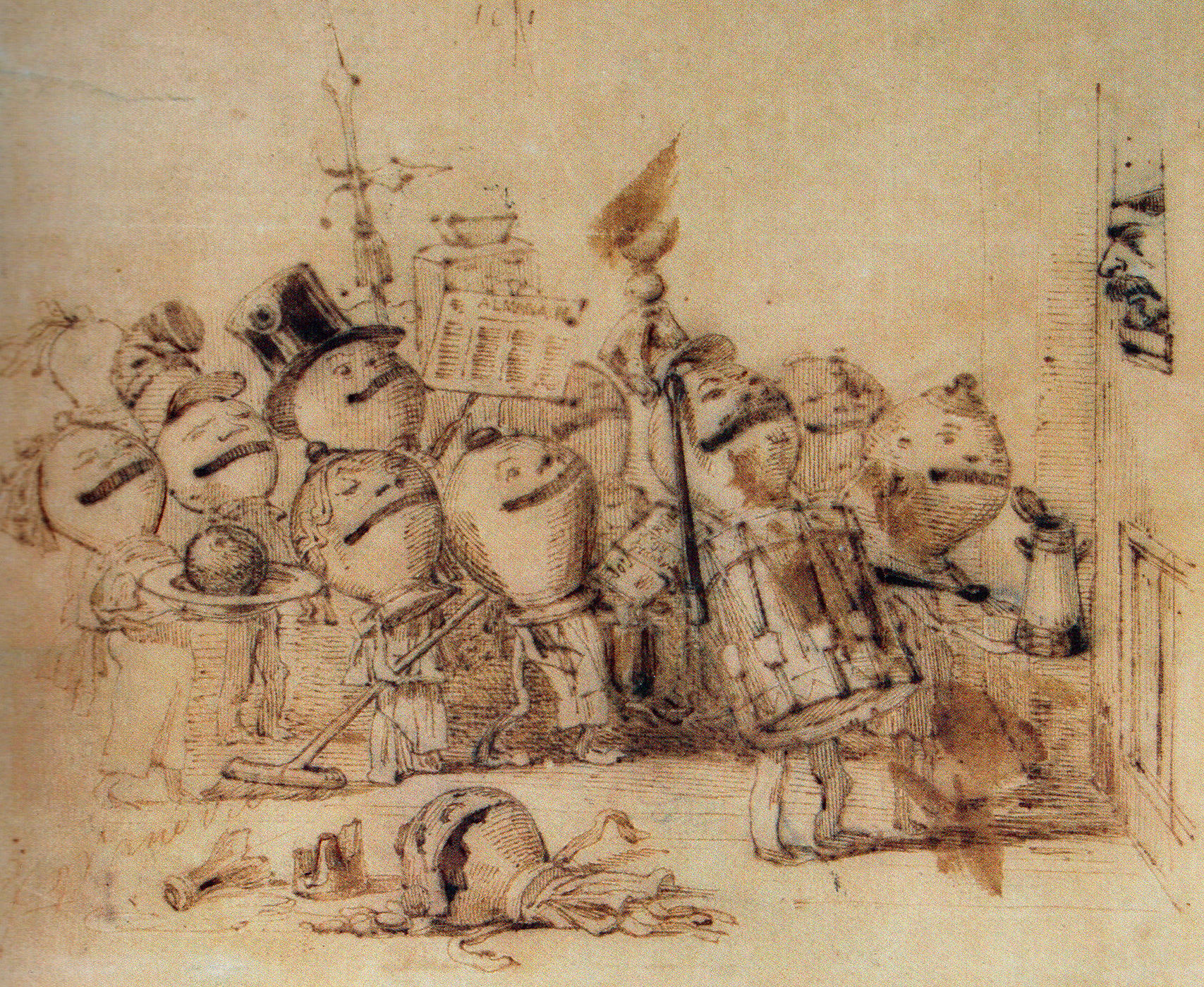

By the early 1840s, Grandville increasingly illustrated books centered around his images, where his illustrations were as important, if not more so, than the text. Collaborating with publishers and contemporary Parisian writers, he was often given free rein over his imagination and the imagery. He produced approximately one book per year, with his name frequently appearing before the authors' on the title page. Not surprisingly, some of his finest and most enduring work emerged during this period. Most of the authors he collaborated with had prior connections or backgrounds with the radical press of the early 1830s.

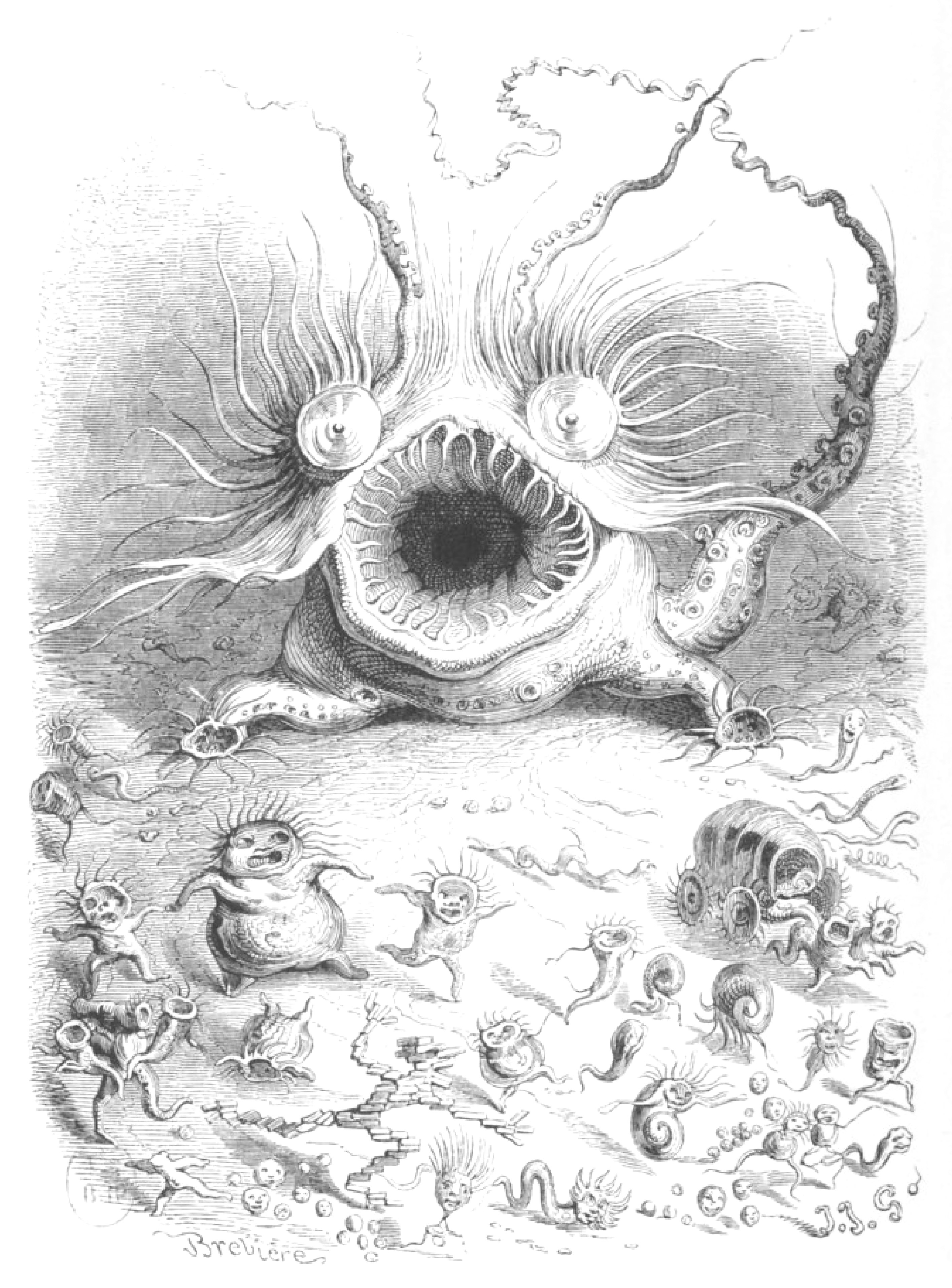

The first of these image-centric projects was Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (Scenes of the Private and Public Life of Animals), a satirical compilation of articles and short stories. It was initially published in serial form over a couple of years, then as a two-volume set in 1842, featuring 320 wood engravings by Grandville. Multiple authors contributed, including Honoré de Balzac, Louis-François L'Héritier, Alfred de Musset, Paul de Musset, Charles Nodier, and Louis Viardot.

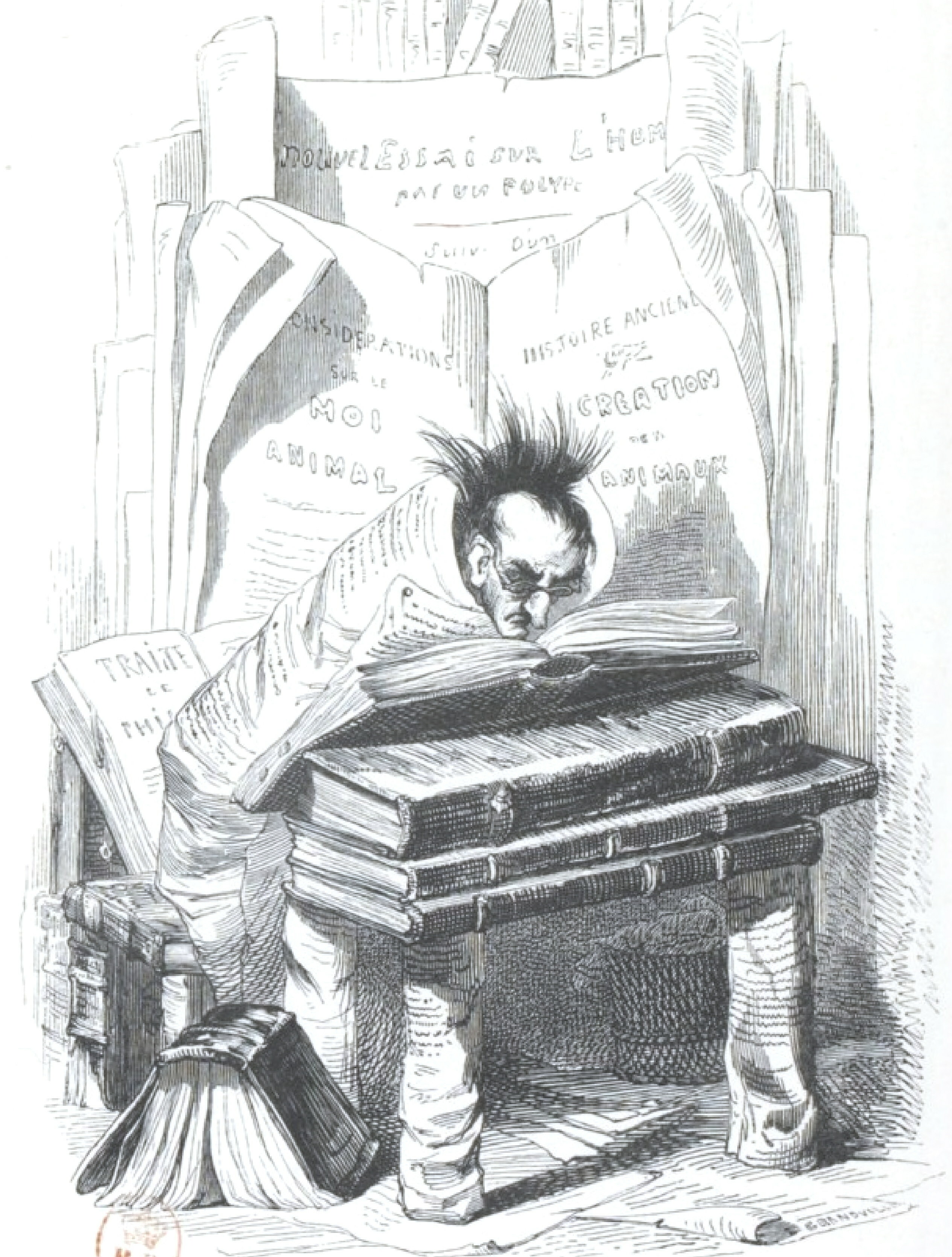

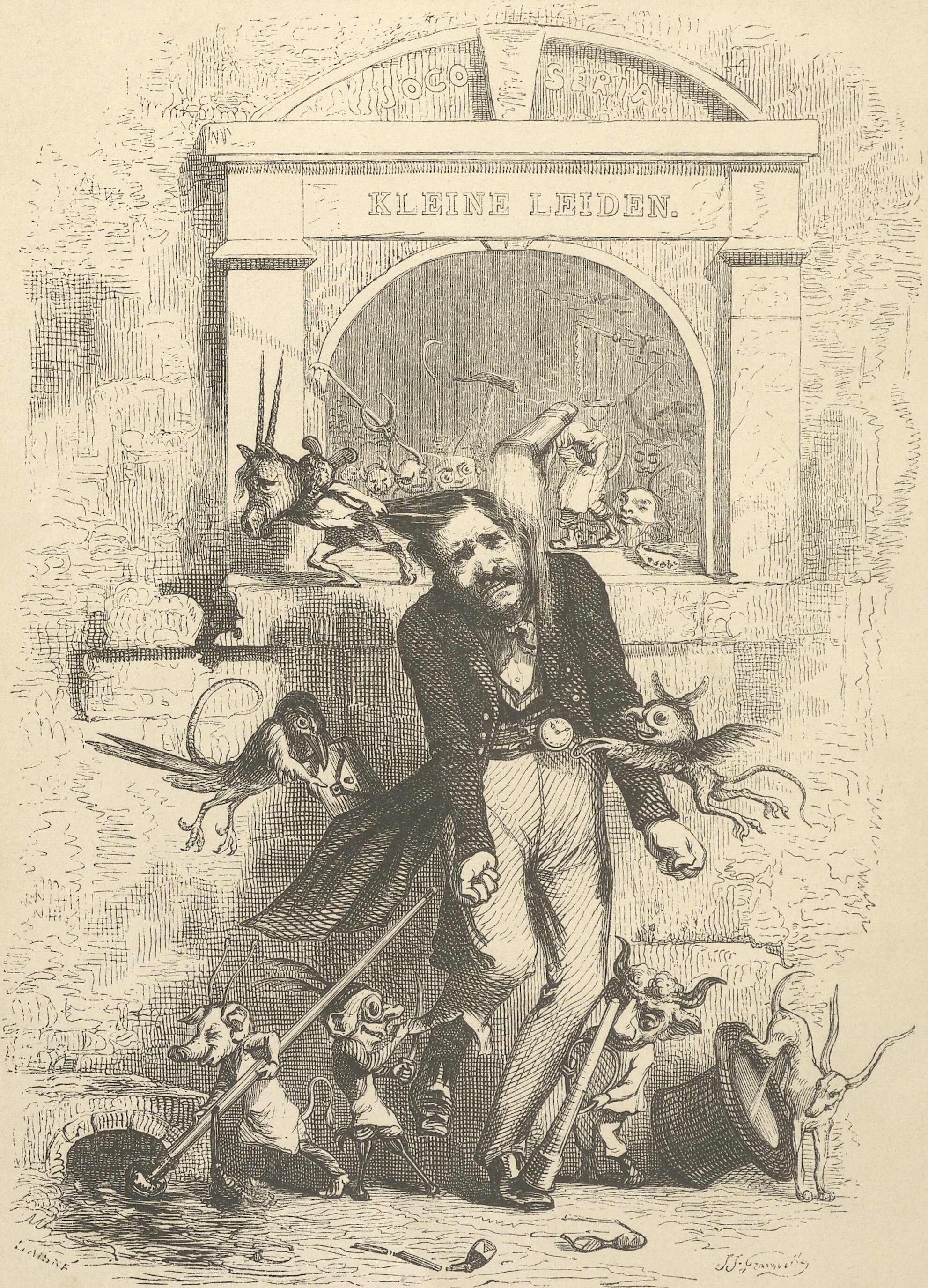

This was followed by Petites misères de la vie humaine (Little Miseries of Human Life) in 1843, with text by Paul-Émile Daurand-ForguesFrench, a contributor to Le Charivari who sometimes published under the pseudonym "Old Nick." Old Nick also co-authored Cent proverbes: têxte par trois Tetes dans un bonnetFrench (One Hundred Proverbs: Text by Three Heads in a Bonnet) with Taxile Delord and Louis Amédée Achard in 1845. Taxile DelordFrench, a writer and critic who served as editor-in-chief of Le Charivari and later entered French politics, provided the text for Un autre monde (Another World) in 1844, a work many consider Grandville's masterpiece, though it was ironically his least commercially successful volume during his lifetime. Delord also wrote Les fleurs animées (Animated Flowers or Flowers Personified), which Grandville completed in 1846 and was published posthumously. Jérôme Paturot à la recherche d'une position sociale (Jérôme Paturot in Search of a Social Position), a social satire by Marie Roch Louis Reybaud published in 1846, was a great success and the last book completed and published during Grandville's lifetime.

3. Artistic Style and Major Works

Grandville's artistic style is renowned for its distinctive imagination, satirical depth, and a unique blend of the absurd and the profound.

3.1. Characteristics and Themes

While Grandville's designs can sometimes appear unnatural and absurd, they consistently demonstrate a keen analysis of character and remarkable inventive ingenuity. His humor is always tempered and refined by a delicate sentiment and a vein of sober thoughtfulness. His ability to provoke politically made his work highly sought after, especially in his early career.

Grandville worked across a wide variety of formats, from illustrating the parlor game Old Maid to mastering illustrated newspaper strips. His illustrations for Le Diable à Paris (The Devil In Paris; 1844-1846) were later utilized by Walter Benjamin in his study of Paris as an urban organism. His most original contributions to the illustrated book form, such as Un Autre Monde, often approach the status of pure surrealism, conceived even before the advent of Freudian psychology. The full title of Un autre monde itself, Another world: Transformations, visions, incarnations, ascents, locomotions, explorations, peregrinations, excursions, stations, cosmogonies, phantasmagoria, reveries, frolics, pranks, fads, metamorphoses, zoomorphoses, lithomorphoses, metempsychoses, apotheoses and other things, encapsulates the breadth of his imaginative and thematic scope.

His most distinctive stylistic elements include anthropomorphic figures, particularly animals with human bodies, and a tendency towards surreal and dreamlike imagery. These elements were frequently employed to offer social commentary, satirizing human nature and the societal norms of his time.

3.2. Key Publications and Projects

Grandville's body of work includes several notable illustrated books and projects that exemplify his unique artistic vision:

- Les Métamorphoses du jour (1829): This early success, a set of 70 lithographs, is a prime example of his use of anthropomorphic figures to satirize human behavior and bourgeois society. It solidified his reputation and established his imaginative approach.

- Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (1842): A satirical compilation featuring 320 wood engravings by Grandville, this project brought together various contemporary authors and showcased his ability to blend social critique with whimsical animal characters. It was a major bestseller of its time.

- Un autre monde (1844): Often considered his masterpiece, this book with text by Taxile Delord is a fantastical journey into a transformed world. Its complex and surreal imagery, full of visions, metamorphoses, and dreamscapes, predates and resonates strongly with later surrealist art. Despite its artistic significance, it was not a commercial success during his lifetime.

- Les fleurs animées (Animated Flowers or Flowers Personified, 1846): Completed shortly before his death and published posthumously, this work, also with text by Taxile Delord, features poetic and satirical images of anthropomorphized flowers, further demonstrating Grandville's unique imaginative concepts.

- Jérôme Paturot à la recherche d'une position sociale (1846): A social satire by Marie Roch Louis Reybaud, this was the last book completed and published during Grandville's lifetime, achieving significant success.

4. Death

A romanticized myth surrounding Grandville's death persisted for over 150 years, suggesting that his bizarre imagery stemmed from a disturbed mind, and that the cumulative tragedies of his family's deaths left him prematurely aged and ultimately drove him to madness, leading to his demise in an insane asylum.

However, recent scholarship largely refutes this narrative. In the days and weeks preceding his death, Grandville continued to produce some of his finest drawings, such as Crime and Expiation, and his correspondence with publishers reveals a clear and rational mind actively anticipating future projects. While the sudden illness and death of his third son, Georges, deeply affected him-with some sources placing it around late 1846 or early 1847, and others as close as three days before Grandville's own death-it did not lead to a descent into madness.

On March 1, 1847, Grandville began suffering from a sore throat, and his condition progressively deteriorated over the following weeks. It has been speculated that he contracted diphtheria. He was eventually admitted to a private clinic, Maison de Santé at 8 Vanves, where two innovative psychiatrists, Félix Voisin and Jean-Pierre Falret, worked. Although the facility treated mentally ill patients among other conditions, Grandville was not considered "mad" and likely died from a throat infection.

Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard, known as Grandville, passed away on March 17, 1847. He was buried in the Cimetière Nord of Saint-Mandé in Paris, beside his first wife and three sons. The artist himself wrote his own epitaph, which has been translated variously as: "Here lies Grandville; he loved everything, made everything live, speak, and walk, but he could not make a way for himself," or "Here lies J. J. Grandville. He could bring anything to life and, like God, he made it live, talk and walk. Only one thing eluded him: how to live a life of his own."

5. Assessment and Legacy

Grandville's art and ideas have been critically evaluated within historical and social contexts, revealing both contemporary reactions and a lasting influence on subsequent generations, particularly in the realms of art and popular culture.

5.1. Contemporary Reactions and Criticisms

Interest in Grandville's art remained relatively high for several decades after his death. His final works were published posthumously, and several of his books were reissued in later editions and translated into other languages, contributing to his enduring reputation. In his honor, Rue Grandville in the Saint-Mandé commune of Paris is named after him, and a monument featuring a bust of Grandville by Ernest Bussière was erected in the Parc de la Pépinière in Nancy in 1893.

Théophile Gautier included a short chapter on Grandville in his Portraits contemporains. More than 25 years after Grandville's death, Gautier observed that Grandville still enjoyed a popular reputation, with his drawings, caricatures, and illustrations widely known. Although Gautier considered Grandville less a colorist than Honoré Daumier and less a poet than Tony Johannot, he asserted the exquisite finesse, liveliness, and skill of Grandville's original pen-and-ink drawings, predicting their increasing value over time and stating that while others might mimic Grandville, they would "not equal it again."

Honoré de Balzac held somewhat ambivalent views of Grandville's work. He was an enthusiastic supporter and collector of Grandville's early print series, and the two collaborated at La Caricature in the early 1830s, where Balzac served as a literary editor and caricatures were an integral part of the newspaper. However, in the 1840s, as publishers began incorporating illustrations into books, Balzac became more critical. He believed that illustrations competed with the written word, distorted and diluted the text, and were undermining the market for novels-a concern perhaps justified by sales figures. Balzac himself contributed chapters to Grandville's Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (1842), which became one of the bestsellers of the 1840s, selling 25,000 copies, while Balzac's first edition novels during the same period typically sold only 1,200 to 3,000 copies.

Charles Baudelaire, a friend and champion of Honoré Daumier, was notably not a fan of Grandville. It appears peculiar that Baudelaire, the author of Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil)-a work known for its dark themes, including poems like Spleen-and a great admirer and translator of Edgar Allan Poe, found Grandville's images frightening. Today, Baudelaire's criticisms often read more like an underhanded compliment. In 1857, Baudelaire wrote: "There are superficial people whom Grandville amuses, but as for me, he frightens me. When I enter into Grandville's work, I feel a certain discomfort, like in an apartment where disorder is systematically organized, where bizarre cornices rest on the floor, where paintings seem distorted by an optic lens, where objects are deformed by being shoved together at odd angles, where furniture has its feet in the air, and where drawers push in instead of pulling out."

5.2. Influence on Later Art and Popular Culture

Grandville's distinctive style and humor had a notable influence on John Tenniel and various other cartoonists for Punch magazine. The art historian H. W. Janson pointed out that Grandville's imagery anticipated various aspects of Dada, Surrealism, and Pop Art. Janson speculated that Marcel Duchamp's Tu m' (1918) might have been inspired by Grandville's View of the Paris Salon from Un autre monde, as both works involve subjects emerging from a two-dimensional painting surface into the real, three-dimensional space of the viewer. Janson also asserted that Grandville's illustration The Finger of God, also from Un autre monde, must have been familiar to Pop artists producing large-scale sculptures, such as César Baldaccini's Le pouce (The Thumb) in 1966.

Grandville's affinity with surrealism has been recognized since the 1930s. His work was included in the Museum of Modern Art's landmark exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism in 1936. However, art historian William Rubin noted the absence of any reference or recognition of Grandville by André Breton in his two manifestos of surrealism, or by other surrealists in the formative years of the movement during the 1920s. After a period of relative obscurity in the early 20th century, Grandville's work became widely reproduced in the 1930s, coinciding with the rise of surrealism as a mainstream movement. It was apparently only in hindsight that André Breton, Georges Bataille, Max Ernst, and others came to recognize Grandville as a significant precursor to the movement, rather than a direct influence. Max Ernst was particularly enthusiastic about Grandville's work, including him in a montage of 40 names titled Max Ernst's favorite poets and painters, originally published in View in 1941, alongside figures such as Bosch, Vinci, Shakespeare, Blake, Poe, Van Gogh, and Chirico. Ernst later created the frontispiece for a 1963 facsimile edition of Un autre monde with the caption "A new world is born. All praise to Grandville."

Grandville's artwork has also permeated popular culture. The British rock band Queen used part of his artwork for their 1991 album Innuendo and alternate pieces for most of the subsequent single releases, including the album's title track, "I'm Going Slightly Mad", "These Are the Days of Our Lives", and "The Show Must Go On". The video clip for "Innuendo" notably featured animated versions of illustrations inspired by Grandville, and the single "I'm Going Slightly Mad" also showcased one of his characters on its sleeve and as the basis for a picture disc release. The American grunge band Alice in Chains similarly utilized a portion of Grandville's artwork for their 1995 self-titled album. Furthermore, the graphic novel Grandville by Bryan Talbot was greatly inspired by Grandville's illustrations. His art is also extensively used in the video game Aviary Attorney, which is set during a fictionalized version of the French Revolution of 1848.

6. Selected Works

- Les Métamorphoses du jour (Metamorphoses of the Day) [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Les_M%C3%A9tamorphoses_du_jour (Category on Commons)], 73 lithographs, Aubert, Paris, 1829

- Voyage pour l'éternitéFrench (Voyage to Eternity) [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Voyage_pour_l%27%C3%A9ternit%C3%A9 (Category on Commons)], 9 lithographs, Aubert, Paris, 1830

- La Silhouette (The Silhouette), 9 lithographs, periodical illustrations, 1829-1831

- La Caricature (The Caricature), 120 lithographs, periodical illustrations, 1830-1835

- Le Charivari (Le Charivari), 106 lithographs, periodical illustrations, 1832-1835

- L'Association Mensuelle lithographique (The Association of Monthly Lithographs), 16 lithographs, 1 etching, 1 engraving, periodical illustrations, 1832-1834

- Le Magasin pittoresque (The Picturesque Store), 67 woodcuts, periodical illustrations, 1833-1857

- 24 breuvages de l'hommeFrench (24 Beverages of Man), 8 lithographs, Bulla, Paris, 1835

- Oeuvres complétes de P. de BerangerFrench (Complete works of P. de Béranger), 38 wood engravings, Fournier et Perrotin, Paris, 1835 (100 wood engravings in 1837 edition)

- La Fontaine's Fables (La Fontaine 's Fables), 258 wood engravings, Fournier et Perrotin, Paris, 1838-1840

- Gulliver's Travels (Voyages de Gulliver), by Jonathan Swift, 346 wood engravings, Fournier et Furne, Paris, 1838

- Robinson Crusoe (Les Aventures de Robinson Crusoe), by Daniel Defoe, 206 wood engravings, Fournier, Paris, 1840

- Les Français peints par eux-mêmes (The French Painted by Themselves), periodical illustrations, 18 wood engravings, 1840

- Fables de Lavalette (Fables of Lavalette), 21 etchings, Paulin et Hetzel, Paris, 1841 (33 etchings in 1847 ed.)

- Fables de Florian (Fables of Florian), 95 wood engravings, Dubochet, Paris, 1842

- Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (Scenes of the Private and Public Life of Animals), 320 wood engravings, Hetzel et Paulin, Paris, 1842

- Petites misères de la vie humaine (Little Miseries of Human Life), by Old Nick & Grandville, 222 wood engravings, Fournier, Paris, 1843

- L'Illustration (The Illustration), 17 wood engravings, periodical illustrations, 1843-1845

- Un autre monde (Another World), text by Taxile Delord, 185 wood engravings, Fournier, Paris, 1844

- Cent proverbes: par trois Tetes dans un bonnetFrench (One Hundred Proverbs: by Three Heads in a Bonnet), by Old Nick, Taxile Delord, & Amédée Achard, 105 wood engravings, Fournier, Paris, 1845

- Jérôme Paturot à la recherche d'une position sociale (Jérôme Paturot in Search of a Social Position), by Louis Reybaud, 186 wood engravings, Dubochet, Paris, 1846

- Les fleurs animées (Animated Flowers or Flowers Personified), text by Taxile Delord, 2 wood engravings, 50 engravings, Gabriel de Gonet, Paris 1846

- Don Quixote (L'Ingénieux hidalgo Don Quichotte de La Mancha), by Cervantes, 18 wood engravings, 8 engravings, Ad Mame et Cie, Tours, 1848