1. Early Life and Background

Jan Žižka's early life was marked by humble beginnings and a period of outlawry before he emerged as a military leader.

1.1. Childhood and Family Environment

Jan Žižka was born around 1360 in the village of Trocnov within the Kingdom of Bohemia. His family, belonging to the lower Czech gentry (zemanéCzech), did not possess extensive estates. An old legend suggests he was born in the forest under an oak tree near his family's homestead. His parents were named Řehoř and Johana, and he had several siblings, though only his brother Jaroslav and sister Anežka are known to historians. The family's coat of arms featured a crayfish.

Documents from 1378 to 1384 indicate Žižka faced long-term financial difficulties. A 1378 document mentions a "Johannes dictus Zizka de Trocnov" as a witness to a marriage contract, suggesting he was of legal age then, placing his birth around 1360. However, some historians, like Václav Tomek, argue this might have been his father, believing Žižka would be too old to achieve such military prowess after 1419 if born in 1360. Others, such as František Šmahel, contend that age would not have hindered his leadership. Petr Čornej notes that "Žižka" was a unique nickname not found among other family members, suggesting it was not a family name. In 1381, Žižka was in Prague to settle an inheritance dispute over the Trocnov estate. A 1384 document mentions his wife, Kateřina, and his sale of a field he received as her dowry. After this, Žižka's name disappears from historical records for two decades, during which he is generally believed to have become a mercenary soldier.

1.2. Outlaw Period

In the early 15th century, Žižka likely managed his family property but faced financial hardship, leading to the sale of parts of their estate. Some sources suggest his father served as a royal gamekeeper before his death in 1407, and Žižka himself might have briefly entered royal service, though evidence remains unclear.

However, from 1406, Žižka began appearing in the "black book" (acta negra maleficorumLatin) of the Rosenberg estate, accused of banditry. The specific reasons for these charges are unknown, but his declared hostility towards Henry III of Rosenberg and the city of České Budějovice suggests he was fighting perceived injustices against his family or asserting his rights. Historian Šmahel attributes the rise of banditry in southern Bohemia to the growing estates of wealthy families like the Rosenbergs and the church, which led to the indebtedness and impoverishment of the lower gentry, causing social tension. Žižka's circumstances may have forced him to leave Trocnov, with some historians speculating he was forcibly dispossessed of his small hereditary property.

As an outlaw, Žižka engaged in violence against his enemies, often allying with local bandits, including Matěj Vůdce (Matthew the Leader), who sought financial gain. His group camped in various locations, including a farm in Sedlo (now part of Číměř), a mill near Lomnice nad Lužnicí, and in the woods. Their income primarily came from robbery, kidnapping for ransom, and attacking small towns, which funded their living expenses and spies. Žižka participated in these raids and was involved in at least one murder, that of a man from Henry of Rosenberg's cohort. He also collaborated with more powerful enemies of Henry of Rosenberg, participating in preparations to conquer Hus Castle near Prachatice in 1408, whose burgrave, Mikuláš of Hus, later became a commander in Žižka's Hussite army. He also negotiated with Aleš of Bítov to conquer Nové Hrady and Třeboň, and with Erhart of Kunštát to capture the stronghold of Slověnice.

Many of Žižka's companions, including Matěj Vůdce, were eventually captured, tortured, and executed. However, Žižka's situation changed on 25 April 1409, when King Wenceslaus IV agreed to resolve his conflict with České Budějovice. On 27 June, the king issued a special letter pardoning Žižka, calling him "faithful and beloved," and ordered the city council of Budějovice to do the same. This suggests the king acknowledged some justification for Žižka's actions in the conflict.

2. Military Career and Activities

Jan Žižka's military career spanned from his early days as a mercenary to his pivotal role as a commander during the Hussite Wars, where he demonstrated unparalleled tactical genius.

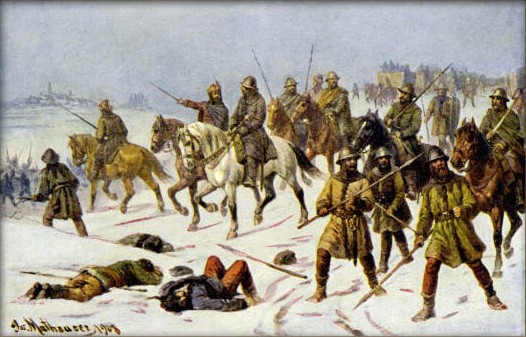

2.1. Mercenary Service and the Battle of Grunwald

Following his pardon, Žižka served as a mercenary in the Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War in 1410. He is believed to have fought on the victorious Polish-Lithuanian side in the Battle of Grunwald (also known as the First Battle of Tannenberg) on 15 July 1410, one of the largest battles in Medieval Europe. The alliance of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, led by King Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) and Grand Duke Vytautas, decisively defeated the Teutonic Knights under Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen. After the battle, Žižka reportedly served in the garrison of the town of Radzyń.

2.2. Royal Service and Influence of Jan Hus

The period of Žižka's activities between 1411 and 1419 is less clear. According to a later account by Lukáš Pražský (1527), Žižka entered the service of Sofia of Bavaria, wife of King Wenceslaus IV, as her chamberlain. He reportedly accompanied Queen Sofia when she attended the preachings of Jan Hus. Given that Hus went into exile in southern Bohemia in 1413, this service must have occurred between 1411 and 1412. The Hussite historian Vavřinec z Březové, who knew Žižka personally, referred to him as a `familiaris regis Bohemiae` (a king's courtier) in 1419, confirming his close association with the royal court. Sixteenth-century chronicles further emphasize Žižka's exceptional position among Wenceslaus IV's servants.

There is a possibility Žižka participated in the Polish king's unsuccessful war against the Teutonic Knights in 1414, though concrete evidence is lacking. Interestingly, a month after this campaign, on 7 November 1414, a house in Na Příkopě street in Prague was purchased by a one-eyed royal "doorman" named Janek. Czech historiography generally identifies this "doorman" with Žižka. On 27 May 1416, this "doorman" Janek sold the house and bought a smaller one in the Old Town. During his time in Prague, Žižka was exposed to the teachings of Jan Hus, a religious reformer whose criticisms of church corruption deeply influenced him.

2.3. Rise to Leadership in the Hussite Wars

Jan Žižka's direct involvement in the Hussite revolution began on 30 July 1419, when he joined a Hussite procession led by the priest Jan Želivský in Prague. The crowd, demanding the release of imprisoned Hussites, stormed the New Town Hall after their demands were rejected, resulting in the First Defenestration of Prague, where councilors were thrown from windows. This event is widely considered the catalyst for the Hussite revolution. King Wenceslaus IV reportedly died 17 days later, likely from shock. The Hussites subsequently seized control of Prague, expelling their opponents.

On 13 November 1419, a temporary armistice was agreed upon between King Sigismund's partisans and the citizens of Prague. Žižka, disapproving of this compromise, left Prague with his followers for Plzeň, one of the kingdom's wealthiest cities, but soon departed from there as well. On 25 March 1420, he achieved his first significant victory in the Hussite Wars at the Battle of Sudoměř, defeating Sigismund's forces. He then proceeded to Tábor, the newly established stronghold of the radical Hussite movement. The Táborite community was characterized by a puritanical ecclesiastical structure and strict military discipline, though its government was democratically organized. Žižka played a crucial role in shaping this new military community, becoming one of its four `hejtman` (captains of the people).

2.4. Innovative Tactics and Weaponry

Žižka's military strategies were highly unorthodox and innovative, fundamentally reshaping warfare during the Hussite Wars.

2.4.1. Wagenburg Tactics

Žižka significantly developed and perfected the use of wagon forts, known as `vozová hradba` in Czech or `Wagenburg` (wagon fort) by the Germans, as mobile fortifications. When facing numerically superior opponents, the Hussite army would arrange carts into squares or circles. These carts were chained together wheel-to-wheel and positioned at an angle, with their corners connected, allowing for quick harnessing of horses if needed. A ditch was often dug in front of this wagon wall by camp followers. Each cart was crewed by 16-22 soldiers, typically including 4-8 crossbowmen, 2 handgunners, 6-8 soldiers armed with pikes or flails (the flail became a distinctive Hussite weapon), 2 shield carriers, and 2 drivers.

Hussite battles typically unfolded in two stages: a defensive phase followed by an offensive counterattack. In the first stage, the army positioned the wagon fort near the enemy and provoked them into battle with artillery fire, which inflicted heavy casualties at close range. When enemy knights finally attacked to avoid further losses, the infantry hidden behind the carts used firearms and crossbows to repel the assault, focusing on shooting horses to neutralize the cavalry's main advantage. Many knights fell as their horses were shot down. As enemy morale waned, the second stage, the offensive counterattack, began. Infantry and cavalry burst out from behind the carts, striking violently at the enemy, often from the flanks. Caught between flanking attacks and shelling from the wagon fort, the enemy was often unable to resist effectively and was forced to withdraw, leaving behind dismounted, heavily armored knights who struggled to escape the battlefield. Hussite armies gained a reputation for not taking captives, contributing to the heavy losses suffered by their opponents.

2.4.2. Use of Gunpowder Weapons

The Hussite Wars also marked the earliest successful battlefield use of early firearms, with Žižka being a key innovator in gunpowder weapon application. He was the first European commander to maneuver medium-caliber cannons on carts between the wagons. The Czechs called their handguns `píšťala` (from which "pistol" is derived) and anti-infantry field guns `houfnice` (from which "howitzer" is derived). The Germans had recently begun corning gunpowder, making it more suitable for smaller, tactical weapons. While a handgunner in an open field with a single-shot weapon was no match for a charging knight, massed and disciplined gunmen behind a castle wall or within a `Wagenburg` could maximize the handgun's potential. Žižka's experience at the Battle of Grunwald informed his understanding of enemy tactics, allowing him to devise new ways to defeat numerically superior forces.

2.5. Major Battles and Crusades

Žižka led the Hussite forces through numerous significant military campaigns and battles against anti-Hussite crusades and internal factions. The Hussite Wars aimed to secure recognition for the Hussite faith, a precursor to the Protestant Reformation. Though primarily religious, the movement was also driven by social issues and fostered Czech national awareness. The Catholic Church declared Hus's teachings heretical, leading to his excommunication in 1411 and his burning at the stake in 1415 after condemnation by the Council of Constance. The wars officially began in July 1419 with the First Defenestration of Prague.

2.5.1. The First Anti-Hussite Crusade

King Sigismund, already King of Hungary and claiming the Bohemian crown, obtained aid from Pope Martin V, who issued a bull on 17 March 1420, proclaiming a crusade "for the destruction of the John Wycliffe, Hussites and all other heretics in Bohemia." Sigismund and numerous German princes, leading a vast army of crusaders attracted by the prospect of pillage, arrived before Prague's walls on 30 June and began a siege. Žižka, a pragmatist, adapted his military strategy to his army, which consisted of farmers and peasants lacking traditional military equipment. He transformed agricultural tools into weapons, such as the agricultural flail into a formidable weapon.

Threatened by Sigismund, the citizens of Prague appealed to the Táborites for assistance. Žižka and his captains led the Táborites to defend the capital, taking a strong position on Vítkov Hill (now in Žižkov, a district named in his honor). On 14 July, Sigismund's armies launched a general attack, with a strong German Crusader force assaulting Vítkov, which secured Hussite communications. Under Žižka's personal leadership, the attack was repelled, and Sigismund's forces abandoned the siege. On 22 August, the Táborites returned to Tábor. Although Sigismund retreated from Prague, his troops held the castles of Vyšehrad and Hradčany. The citizens of Prague besieged Vyšehrad, and by late October, the garrison was near capitulation due to famine. Sigismund attempted to relieve the fortress but was decisively defeated by the Hussites near Pankrác on 1 November. Vyšehrad and Hradčany then capitulated, and most of Bohemia fell to the Hussites.

Žižka subsequently engaged in continuous warfare with Sigismund's partisans, particularly Oldřich II of Rožmberk. Through these struggles, the Hussites gained control of most of Bohemia. While there was a proposal to elect Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania to the throne, the estates of Bohemia and Moravia met at Čáslav on 1 June 1421 and established a provisional government of twenty members from all political and religious factions. Žižka, participating in the deliberations, was elected one of Tábor's two representatives.

Žižka swiftly suppressed disturbances by the fanatical Adamites. He continued his campaigns against Romanists and Sigismund's supporters, capturing and rebuilding a small castle near Litoměřice. He retained possession of this castle, naming it `Chalice` (KalichCzech) in accordance with Hussite custom, and adopted the signature "Žižka of the Chalice." This was the only property Žižka claimed for himself during the Hussite Wars, a fact unusual for the era and distinguishing him from his contemporaries. Later that year, during the siege of Rabí Castle, he was severely wounded and lost his remaining eye, becoming totally blind. Despite this, he continued to command the Táborite armies.

2.5.2. The Second Anti-Hussite Crusade

At the end of 1421, Sigismund again attempted to subjugate Bohemia, capturing the important town of Kutná Hora. The predominantly German citizens of Kutná Hora killed some Hussites and closed the city gates to Žižka's armies, which were camped outside. Sigismund's forces arrived and surrounded the Hussites. Žižka, leading the united Táborite and Prague armies, though trapped, executed what some historians call the first mobile artillery maneuver in history. He broke through enemy lines and retreated to Kolín. After receiving reinforcements, he attacked and defeated Sigismund's unsuspecting army at the village of Nebovidy between Kolín and Kutná Hora on 6 January 1422. Sigismund lost 12,000 men and barely escaped. Sigismund's forces made a final stand at Battle of Německý Brod on 10 January, but the city was stormed by the Czechs, and its defenders were massacred, contrary to Žižka's orders.

2.6. Internal Conflicts and Civil War

Early in 1423, internal divisions within the Hussite movement escalated into civil war. Žižka, leading the Táborites, defeated the forces of Prague and the Utraquist nobles at Hořice on 20 April. Soon after, news of a new crusade against Bohemia prompted the Hussites to agree to an armistice at Konopiště on 24 June. Once the crusaders dispersed, internal strife resumed. During his temporary rule over Bohemia, Prince Sigismund Korybut of Lithuania had appointed Bořek, lord of Miletínek, as governor of Hradec Králové. Bořek belonged to the moderate Utraquist faction. After Sigismund Korybut's departure, the democratic party gained influence in Hradec Králové, and the city refused to recognize Bořek's authority, appealing to Žižka for aid. Žižka responded, defeating the Utraquists under Bořek at the farm of Strachov (near modern-day Kukleny in Hradec Králové) on 4 August 1423.

Žižka then attempted to invade Hungary, ruled by his old enemy King Sigismund. Though this Hungarian campaign was ultimately unsuccessful due to the Hungarians' numerical superiority, it is considered one of Žižka's greatest military feats for the skill he demonstrated in retreat. In 1424, civil war again erupted in Bohemia. Žižka decisively defeated the "Praguers" and Utraquist nobles at the battle of Skalice on 6 January, and at the Battle of Malešov on 7 June. In September, he marched on Prague. On 14 September, peace was brokered between the Hussite factions through the influence of John of Rokycany, who later became the Utraquist archbishop of Prague. The reunited Hussites agreed to attack Moravia, parts of which were still held by Sigismund's partisans, with Žižka leading the campaign.

3. Loss of Sight and Continued Command

Jan Žižka's military career is remarkable for his continued, successful command despite losing his sight. He had already lost one eye earlier in his life, and in 1421, during the siege of Rabí Castle, he was severely wounded by an arrow that struck his remaining eye, rendering him completely blind.

Despite this profound disability, Žižka continued to lead the Táborite armies with exceptional success. His ability to command, strategize, and inspire his troops while blind is a testament to his military genius and unwavering determination. This period highlights his reliance on his keen intellect, memory of terrain, and the disciplined execution of his orders by his loyal subordinates. His continued victories, even after becoming totally blind, further solidified his legendary status among the Hussites and instilled fear in his enemies, who sometimes attributed his success to divine intervention.

4. Death

Jan Žižka died on the Moravian frontier near Přibyslav, during the siege of the castle in Přibyslav (in what is today Žižkovo Pole), on 11 October 1424. Traditionally, his death was attributed to the plague. However, modern historical research has largely dismissed this theory. The theory of arsenic poisoning was also ruled out after examination of his skeletal remains. Current historical consensus considers a purulent disease, specifically a carbuncle, as the most likely cause of his death.

According to chronicler Piccolomini, Žižka's dying wish was for his skin to be used to make drums, so he could continue to lead his troops even after death. Such was the reverence for Žižka that his soldiers, after his death, called themselves `Sirotci` ("the Orphans") because they felt they had lost their father. His enemies reportedly remarked, "The one whom no mortal hand could destroy was extinguished by the finger of God."

Žižka was initially interred in the church of Saints Peter & Paul in Čáslav. However, in 1623, his remains were removed and his grave destroyed by order of Emperor Ferdinand II. He was succeeded as leader of the radical Hussites by Prokop the Great.

5. Assessment and Legacy

Jan Žižka is widely regarded as one of the most brilliant military commanders in history, leaving an indelible mark on Czech history and national identity.

5.1. Military Achievements and Tactical Genius

Žižka's strategic brilliance and his undefeated record in battle are central to his legacy. He is often cited as one of the greatest military commanders of all time, particularly for his ability to train and equip his peasant army to repeatedly defeat highly trained and heavily armored opponents, who often outnumbered his own troops. He masterfully exploited geographical features and maintained strict discipline within his forces.

His innovative tactics, such as the `Wagenburg` (wagon fort) and the effective use of early gunpowder weapons like handguns (`píšťala`) and cannons (`houfnice`), were revolutionary. He was the first European commander to maneuver medium-caliber cannons on carts, anticipating later artillery developments. His victories at battles like Sudoměř, Vítkov Hill, and Kutná Hora demonstrated his tactical acumen, particularly his ability to break sieges and execute mobile artillery maneuvers. The series of battles from Kutná Hora to Německý Brod showcased a prolonged and devastating pursuit aimed at neutralizing enemy forces, a rare occurrence in medieval warfare.

Žižka's genius also lay in his understanding of his own peasant and artisan troops, and the opposing cavalry. He adapted familiar tools into effective weapons, such as the flail, and emphasized the role of heavy artillery and handguns not just for damage but also for causing panic and obscuring enemy vision. The Hussite army was among the first to use firearms and heavy artillery to decimate enemy forces on the battlefield, whereas previously, heavy artillery was primarily used for siege warfare. His leadership transformed an untrained populace into a formidable fighting force, emphasizing discipline through regulations like the "military internal rules of Žižka's New Brotherhood" (1423), which prohibited theft, gambling, looting, and drunkenness.

5.2. Status as a Czech National Hero

Žižka holds immense symbolic importance and cultural impact, recognized as a pivotal figure in Czech national identity and pride. His undefeated record and his role in defending the Hussite faith against powerful crusades have cemented his status as a national hero. He is seen as a "warrior of God" by his followers and a terrifying, almost supernatural, opponent by his enemies. His ability to continue commanding armies even after losing both eyes further contributed to his legendary aura, with Hussites viewing it as a sign of divine favor.

A monument on Vítkov Hill in Prague, commemorating Žižka and his 1420 victory, is the third-largest bronze equestrian statue in the world. Other statues honoring him can be found in Tábor, his birthplace Trocnov, and Sudoměř.

5.3. Criticisms and Controversies

While celebrated, Žižka's legacy is not without criticism. Some historians acknowledge that while he fought for self-defense and church reform, his campaigns involved significant bloodshed, massacres, and the destruction of churches and villages. For instance, the massacre of defenders at Německý Brod occurred despite his orders. However, it is also noted that Žižka occasionally showed mercy, unlike his enemies who often spared no one. After the disobedience at Německý Brod, Žižka reportedly ordered his entire army to pray for forgiveness and subsequently established strict military laws that applied to himself as well. This suggests a more complex character than a simple, bloodthirsty warrior. He is often seen as the "man of the sword" complementing Jan Hus, the "man of God," with both figures eternally linked in Czech national identity.

6. Jan Žižka in Popular Culture

Jan Žižka's enduring cultural significance is reflected in his numerous representations across various media.

6.1. Literature

Žižka is a prominent character in literature. He is the hero of a novel by George Sand and a German epic by Meissner. The Czech writer Alois Jirásek penned a Bohemian tragedy featuring Žižka. He also appears as a main character in David B.'s graphic novella The Armed Garden. In Japanese manga, Žižka is a key figure in 乙女戦争 ディーヴチー・ヴァールカDívčí VálkaJapanese (2013) by Kouichi Ohnishi, which depicts the Hussite Wars from a Hussite perspective.

6.2. Films

Žižka is a central figure in the "Hussite Revolutionary Trilogy" directed by Otakar Vávra, with Zdeněk Štěpánek portraying him. This trilogy includes Jan Hus, Jan Žižka, and Against All. He was also played by Tadeusz Schmidt in the 1960 Polish film Knights of the Teutonic Order and by Ilja Prachař in the 1968 Czechoslovak film Na Žižkově válečném voze. The 2013 animated film The Hussites features a protagonist named Záboj who serves as the film's version of Žižka.

More recently, the 2022 film Jan Žižka (English title Medieval), directed by Petr Jákl and starring Ben Foster as Žižka, explores his youth. It is noted as the most expensive Czech film ever made and was released on Netflix in 2022.

6.3. Games

Jan Žižka's presence in modern entertainment extends to various video and board games:

- In Age of Empires II: Definitive Edition - Dawn of the Dukes, players can engage in a single-player campaign featuring Jan Žižka.

- Age of Empires III includes Hussite wagons as a unit for the German civilization, with their infobox directly mentioning "John Zizka."

- He appears as a default general for the Bohemia faction in Europa Universalis II.

- Field of Glory II: Medieval features a Hussite campaign where players take on the role of Jan Žižka.

- Žižka is the main protagonist in the upcoming independent 3D real-time strategy game Songs of the Chalice, set in 1419-1420.

- He is one of the legendary cavalry commanders in the mobile game ROK (Rise of Kingdoms).

- The game Hrot includes a power-up called Calvaria of Čáslav, referencing the skull fragment attributed to Žižka found in Čáslav.

- In the 2020 expansion New Leaders and Wonders for the board game Through the Ages: A New Story of Civilization, Žižka is an Age I leader.

- He appears in the DLC Tourney at the Bear Rock for 1428: Shadows over Silesia, set in 1409.

- Žižka is a main character in Kingdom Come: Deliverance II, set in 1403, where he loses an eye after being shot by Hynek. His likeness is modeled after Czech actor Stanislav Majer, with Adrian Bouchet voicing him in English.

6.4. Other Cultural References

Beyond specific media, Žižka's name and deeds are commemorated in various other forms:

- In early 1917, the 3rd Czechoslovak Rifle Regiment of the Czechoslovak Legions in Russia was named "Jan Žižka z Trocnova."

- During World War II, several military units were named after Jan Žižka, including the 1st Czechoslovak Partisan Brigade of Jan Žižka, an early anti-Nazi guerrilla unit in occupied Czechoslovakia, and a Yugoslav partisan brigade of the same name formed in western Slavonia in 1943, operating in areas with a large Czech and Slovak minority.

- Monuments honoring Žižka exist in various locations, including the prominent equestrian statue on Vítkov Hill in Prague, and statues in Tábor, Trocnov, and Sudoměř.

7. Related Topics

- Jan Hus

- Hussite Wars

- Taborites

- Wagenburg

- Prokop the Great