1. Overview

Jan van Eyck, born before 1390 and active in Bruges until his death on July 9, 1441, was a pivotal Flemish painter and a leading figure of the Early Netherlandish movement and the Northern Renaissance. Though often mistakenly credited with inventing oil painting, his innovations in oil techniques, including the use of glazes for luminous effects and meticulous detail, revolutionized the medium and emphasized an unprecedented naturalism and realism in art. His artistic contributions spanned both secular and religious themes, encompassing altarpieces, single-panel religious figures, and commissioned portraits. Key works such as the Ghent Altarpiece and the Arnolfini Portrait showcase his mastery. Van Eyck was unique among his contemporaries for consistently signing his works with variations of his motto, ALS ICH KAN (Als ich kanAs I canDutch), a clever pun on his name, often rendered in Greek characters.

2. Life

Jan van Eyck's life was marked by his early artistic training, his distinguished career as a court painter and diplomat for powerful dukes, and his settled private life in Bruges, culminating in his death in 1441.

2.1. Early life and education

Little is definitively known about Jan van Eyck's early life; neither his exact birth date nor place is fully documented, though he is believed to have been born around 1380 or 1390, most likely in Maaseik (then Maaseyck), Limburg, in present-day Belgium. The earliest extant record of his life dates from 1422 to 1424, when payments were made to "Meyster Jan den malre" (Master Jan the painter) at the court of John III the Pitiless in The Hague. At this time, he was already an established master painter, holding the rank of valet de chambre (chamberlain) and employing one or two assistants, suggesting he was born no later than 1395. The belief that he was born in Maaseik, a borough of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, was noted in the late 16th century by Ghent humanists Marcus van Vaernewyck and Lucas de Heere, a theory supported by his name "van Eyck" ("from Eyck") and the fact that his daughter, Lievine, entered a nunnery in Maaseik after his death. His preparatory drawing for Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Albergati also features notes written in the Maasland dialect.

Jan van Eyck had a sister named Margareta and at least two brothers who were also painters: Hubert (died 1426), with whom he likely served his apprenticeship, and Lambert, active between 1431 and 1442. The order of their births remains unestablished. Another significant, younger painter, Barthélemy van Eyck, who worked in Southern France, is presumed to be a relative. The specifics of Jan's education are unknown, but his proficiency in Latin and his use of Greek and Hebrew alphabets in his inscriptions indicate a classical education, a rare achievement among painters of his time, which would have made him particularly appealing to the erudite Philip the Good.

2.2. Court painter and diplomat

Jan van Eyck initially served as an official to John of Bavaria-Straubing, who governed Holland, Hainault, and Zeeland. During this period, he had already established a small workshop and was involved in the redecoration of the Binnenhof palace in The Hague. Following John's death in 1425, van Eyck relocated to Bruges, where he gained the patronage of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, around 1425. From this point forward, his activities at court are relatively well-documented. He served not only as a court artist but also as a diplomat, and was a senior member of the Tournai painters' guild. On October 18, 1427, the Feast of St. Luke, he traveled to Tournai to attend a banquet held in his honor, alongside fellow prominent artists Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden.

His court salary afforded him significant financial stability and artistic freedom, liberating him from the constant need for commissioned work. Over the subsequent decade, van Eyck's reputation and technical skill advanced remarkably, largely due to his innovative methods for handling and manipulating oil paint. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his fame persisted, and he remained highly regarded for centuries. His revolutionary approach to oil painting was so profound that it fostered a myth, propagated by Giorgio Vasari and Karel van Mander, that he had invented the medium. While oil painting techniques for wood statues and other objects predate van Eyck, as evidenced by Theophilus Presbyter's 1125 treatise On Divers Arts, it is widely accepted that the van Eyck brothers were among the first Early Netherlandish painters to effectively employ oil for detailed panel paintings, achieving unprecedented effects through the use of glazes and wet-on-wet techniques.

Jan's brother, Hubert van Eyck, collaborated on Jan's most celebrated work, the Ghent Altarpiece, which art historians generally believe Hubert began around 1420 and Jan completed in 1432. Another brother, Lambert, is mentioned in Burgundian court documents and may have managed Jan's workshop after his death.

Considered revolutionary during his lifetime, van Eyck's artistic designs and methods were extensively copied and reproduced. His distinctive motto, ALS ICH KAN (Als ich kanAs I canDutch), a pun on his name, first appeared in 1433 on Portrait of a Man in a Turban, signifying his growing artistic self-confidence. The period between 1434 and 1436 is often considered his peak, during which he produced masterpieces such as the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, Lucca Madonna, and Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele. Van Eyck undertook several "secret" diplomatic journeys on behalf of Philip the Duke of Burgundy between 1426 and 1429, for which he received multiple times his annual salary. While their exact nature remains unknown, these missions likely involved his role as an envoy for the court. A journey in 1426 to "certain distant lands," possibly the Holy Land, is suggested by the remarkably accurate topographical depiction of Jerusalem in The Three Marys at the Tomb, a painting completed by his workshop around 1440.

A more extensively documented commission was his journey to Lisbon in 1428 with a delegation tasked with preparing for the Duke's marriage to Isabella of Portugal. Van Eyck's specific assignment was to paint the bride's portrait, allowing the Duke to visualize her before their wedding. Due to the plague in Portugal, the court was itinerant, and the Dutch party met them at the remote Castle of Avis. Van Eyck spent nine months there, returning to the Netherlands with Isabella, who married Philip on Christmas Day, 1429. While the princess may not have been particularly attractive, van Eyck depicted her with dignity, without concealing her imperfections in the now-lost portrait. Following his return, he focused on completing the Ghent Altarpiece, which was consecrated on May 6, 1432, at Saint Bavo Cathedral during an official ceremony for Philip. Records from 1437 indicate that he was highly esteemed by the highest ranks of Burgundian nobility and received numerous foreign commissions.

2.3. Marriage and private life

Around 1432, Jan van Eyck married Margaret, who was 15 years his junior. During the same period, he acquired a house in Bruges. Margaret is not mentioned in records prior to his relocation to Bruges, where their first of two children was born in 1434. Very little is known about Margaret; even her maiden name has been lost, with contemporary records primarily referring to her as "Damoiselle Marguerite." Her attire in her portrait, though fashionable, does not possess the lavishness seen on the bride in the Arnolfini Portrait, suggesting she may have been of lower aristocratic birth. After Jan's death, Margaret, as the widow of a renowned painter, was granted a modest pension by the city of Bruges, a portion of which she invested in lottery.

2.4. Death

Jan van Eyck died on July 9, 1441, in Bruges and was initially buried in the graveyard of the Church of St Donatian. As a gesture of profound respect, Philip the Good made a one-off payment to Jan's widow, Margaret, equivalent to the artist's annual salary. Van Eyck left behind numerous unfinished works, which were subsequently completed by the journeymen of his workshop. Following his death, his brother Lambert van Eyck took over the management of the workshop, while Jan's artistic reputation and stature continued to grow steadily. In early 1442, Lambert arranged for Jan's body to be exhumed and reinterred within the more prominent St. Donatian's Cathedral.

In 1449, the Italian humanist and antiquarian Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli recognized van Eyck as a painter of remarkable skill and significance. His talent was further acknowledged by Bartolomeo Facio in his 1456 work, ensuring his place in the historical records of art.

3. Artistic career and works

Jan van Eyck's artistic career was prolific, encompassing both religious and secular subjects, marked by significant innovations and collaborations that cemented his place as a leading master of the Northern Renaissance.

3.1. Major works

Jan van Eyck produced paintings for private clients in addition to his court commissions. Approximately 20 to 25 (sources vary) of his paintings confidently attributed to him survive today, all dated between 1432 and 1439. Of these, ten, including the Ghent Altarpiece, bear his signature and date. In 1998, critic Holland Cotter noted the complex relationship between art historians and museums in attributing authorship, observing that about 10 of the 40 works considered originals in the mid-1980s were vigorously contested by leading researchers as workshop creations.

Van Eyck's diverse output includes single panels, diptychs (some since dismantled), triptychs, and polyptych panels. While it is assumed, given the demand of the era, that he produced multiple triptychs, only the Dresden Triptych is fully preserved. Several extant portraits are believed to have originally served as wings of dismantled polyptychs, indicated by signs such as hinges on original frames, the sitter's orientation, praying hands, or the inclusion of iconographical elements in what otherwise appear to be secular portraits.

3.1.1. Ghent Altarpiece

The Ghent Altarpiece is Jan van Eyck's most monumental and celebrated work, commissioned by the wealthy merchant, financier, and politician Jodocus Vijdts and his wife, Elisabeth Borluut. Begun around 1420 by his brother Hubert van Eyck, the polyptych was completed by Jan in 1432 after Hubert's death in 1426. It was officially consecrated on May 6, 1432, at Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent during a ceremony attended by Philip the Good. The altarpiece is widely regarded as "the final conquest of reality in the North," distinguished from the great works of the Early Renaissance in Italy by its rejection of classical idealization in favor of a meticulously faithful observation of nature.

The iconography of the altarpiece is rich and layered. The Virgin Mary, a central figure, wears a crown adorned with flowers and stars, appearing as a bride. She is depicted reading from a girdle book draped with green cloth, an element possibly inspired by Robert Campin's Virgin Annunciate. The panel features several motifs that would reappear in Jan van Eyck's later works, cementing Mary's status as the Queen of Heaven. Notably, the arched throne above Mary contains an inscription from the Book of Wisdom (7:29): "She is more beautiful than the sun and the army of the stars; compared to the light she is superior. She is truly the reflection of eternal light and a spotless mirror of God." Wording from the same biblical source also appears on the hem of Mary's robe, on the frame of Madonna in the Church, and on her dress in Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele.

3.1.2. Turin-Milan Hours

Since 1901, Jan van Eyck has frequently been identified as the anonymous artist known as "Hand G" of the Turin-Milan Hours, an important illuminated manuscript (though some scholars propose Hand G was a follower). If this attribution is accurate, the Turin illustrations represent the sole surviving works from van Eyck's early period. According to Thomas Kren, the early dates associated with Hand G precede any known panel paintings in van Eyck's style, prompting "provocative questions about the role that manuscript illumination may have played in the vaunted verisimilitude of Eyckian oil painting."

Evidence supporting the attribution to van Eyck includes the fact that many figures, while largely belonging to the International Gothic style, reappear in some of his later works. Additionally, the presence of coats of arms linked to the Wittelsbach family, with whom van Eyck had connections in The Hague, and the resemblance of some figures in the miniatures to the horsemen in the Ghent Altarpiece, further bolster this theory.

Most of the Turin-Milan Hours were destroyed by fire in 1904, surviving only through photographs and copies. At most, only three pages attributed to Hand G remain: those with large miniatures of the Birth of John the Baptist, the Finding of the True Cross, and the Office of the Dead (or Requiem Mass), including the bas-de-page miniatures (unframed images illuminating the bottom of a page) and initials of the first and last of these. The Office of the Dead often evokes Jan's later Madonna in the Church (c. 1438-1440). Four additional miniatures were lost in the 1904 fire: all elements of the pages featuring The Prayer on the Shore (also known as Duke William of Bavaria at the Seashore or The Sovereign's prayer), the night-scene of the Betrayal of Christ (which was already described as "worn" before the fire), the Coronation of the Virgin and its bas-de-page, and the large seascape only of the Voyage of St Julian & St Martha. Art historian Albert Châtelet also attributes parts of The Intercession of Christ and the Virgin in the Louvre to Hand G.

3.1.3. Religious paintings

Beyond the monumental Ghent Altarpiece, Jan van Eyck's religious works predominantly feature the Virgin Mary as the central figure. She is typically depicted seated, adorned with a jewel-studded crown, tenderly cradling a playful Child Christ who gazes at her and gently grasps the hem of her dress. This posture and interaction recall the 13th-century Byzantine tradition of the Eleusa icon (Virgin of Tenderness). Mary is sometimes shown engrossed in a Book of Hours and typically wears a red garment. In the 1432 Ghent Altarpiece, Mary is presented as the Queen of Heaven, wearing a crown embellished with flowers and stars, dressed as a bride, and reading from a girdle book draped with green cloth, an element possibly borrowed from Robert Campin's Virgin Annunciate.

Van Eyck commonly portrays Mary as an apparition appearing before a kneeling lay donor engaged in prayer, a convention often seen in Northern donor portraits of the period. In Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele (1434-1436), Joris van der Paele appears to pause from reflecting on a passage in his hand-held bible as the Virgin and Child, accompanied by two saints, miraculously manifest before him, seemingly embodying his prayer.

Mary's prominent role in van Eyck's art must be understood within the context of the fervent contemporary cult and veneration surrounding her. In the early 15th century, Mary's significance as an intercessor between the divine and Christian believers greatly increased. The doctrine of purgatory, as an intermediary state for souls before admittance to heaven, was at its height. Prayer was considered the most direct means to shorten one's time in limbo, while the wealthy could commission new churches, extensions to existing ones, or devotional portraits to secure their spiritual future. Concurrently, there was a growing trend towards sponsoring requiem masses, often stipulated in wills, a practice actively supported by figures like Joris van der Paele, who endowed churches with embroidered cloths, chalices, plates, and candlesticks through such income.

Van Eyck typically assigns Mary three primary roles: Mother of Christ, the personification of the "Ecclesia Triumphans" (the Triumphant Church), or Queen of Heaven. The concept of Mary as a direct metaphor for the Church itself is particularly pronounced in his later paintings. In Madonna in the Church, her towering figure dominates the cathedral's interior, with her head nearly reaching the height of the approximately 60 ft high gallery. Art historian Otto Pächt described the panel's interior as a "throne room" that envelops her like a "carrying case." This intentional distortion of scale, also seen in his Annunciation, draws from the works of 12th- and 13th-century Italian masters such as Cimabue and Giotto, reflecting an Italo-Byzantine tradition that emphasizes her profound identification with the cathedral itself. While 19th-century art historians initially interpreted her colossal size as a mistake of a relatively immature painter, Erwin Panofsky first proposed in 1941 that her scale represented her embodiment as the Church. Till-Holger Borchert further asserted that van Eyck depicted "the Church" itself, rather than merely "the Madonna in a church."

Van Eyck's later works are distinguished by their exceptionally precise and detailed architectural renderings, though these are not based on actual historical buildings. He likely aimed to create an ideal and perfect sacred space for Mary's apparition, prioritizing visual impact over strict physical feasibility. The structures in all of van Eyck's works are imagined and represent an idealized formation of what he considered a perfect architectural environment. This is evident in features unlikely in a contemporary church, such as the placement of a round arched triforium above a pointed colonnade in the Berlin work.

His Marian paintings are characterized by complex depictions of both physical space and intricate light sources. Many of van Eyck's religious compositions feature a condensed interior space, subtly managed and arranged to evoke intimacy without feeling constrained. For example, in the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, light streams from both the central portico and the side windows. The floor-tiles, when compared to other elements, indicate that the figures are merely about 6 ft from the columned loggia screen, suggesting that Rolin would have had to squeeze to pass through the opening. The architectural elements in Madonna in the Church are so specifically detailed, and the interplay of Gothic and contemporary architecture so precisely delineated, that many art and architecture historians have concluded van Eyck possessed significant architectural knowledge, enabling him to make nuanced distinctions. Despite the accuracy of these descriptions, which has led scholars to attempt to link the painting with particular buildings, the structures in van Eyck's works are fundamentally imagined, representing an idealized architectural space.

The Marian works are extensively adorned with inscriptions. The lettering on the arched throne above Mary in the Ghent Altarpiece is derived from a passage in the Book of Wisdom (7:29). Similar wording from this source also appears on the hem of her robe, on the frame of Madonna in the Church, and on her dress in Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele. While inscriptions are present across all of van Eyck's paintings, they are particularly prominent in his Marian works, where they serve multiple functions. They imbue portraits with life and give voice to those venerating Mary, but also serve a practical purpose. Given that contemporary religious works were often commissioned for private devotion, these inscriptions may have been intended to be read as an incantation or as personalized indulgence prayers. Craig Harbison notes that van Eyck's privately commissioned works are unusually heavily inscribed with prayers, suggesting that these words may have functioned similarly to prayer tablets, or more precisely, "Prayer Wings," as seen in the London Virgin and Child triptych.

3.1.4. Secular portraits

Jan van Eyck was a highly sought-after portrait artist. The increasing prosperity across northern Europe meant that portraiture was no longer the exclusive domain of royalty or the high aristocracy. The emergence of a merchant middle class and a growing awareness of humanist ideals of individual identity fueled a rising demand for portraits.

Van Eyck's portraits are distinguished by his innovative manipulation of oil paint and his meticulous attention to detail. His keen observational skills and his technique of applying thin, translucent layers of glazes allowed him to achieve intense color and tone. He pioneered the art of portraiture during the 1430s, earning admiration as far away as Italy for the naturalness of his depictions. Today, nine three-quarters view portraits are confidently attributed to him. His influential style was widely adopted, most notably by van der Weyden, Petrus Christus, and Hans Memling.

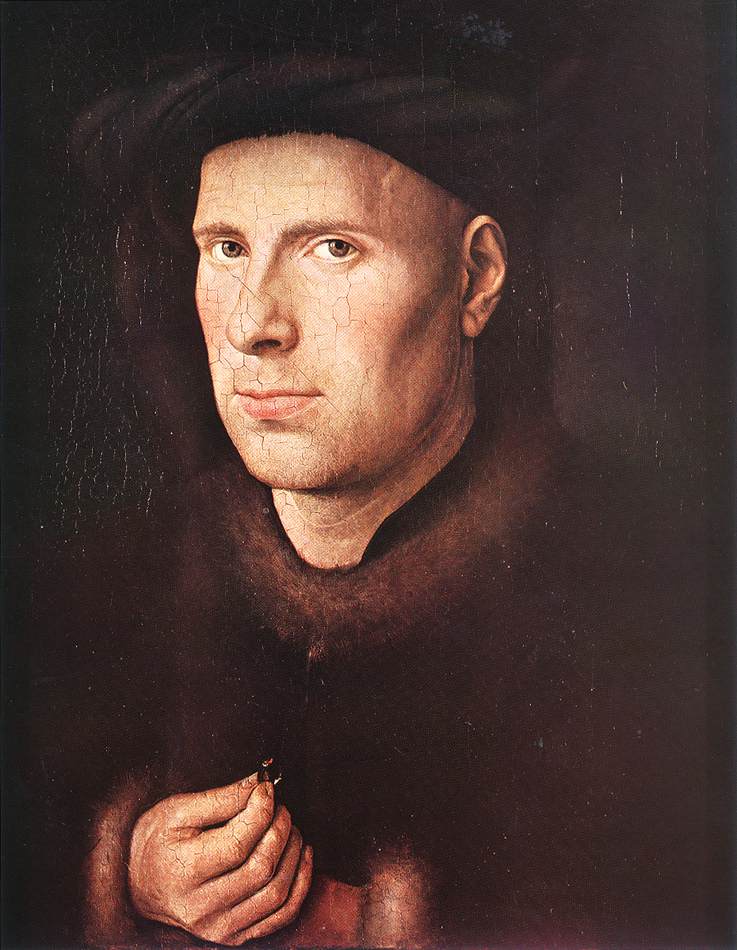

The small Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon, dating to around 1430, is his earliest surviving portrait and already exhibits many elements that would become characteristic of his portraiture style. These include the three-quarters view, a type he revived from antiquity that rapidly spread across Europe, as well as directional lighting, an elaborate headdress, and, for single portraits, the framing of the figure within an undefined, narrow space set against a flat black background. The painting is highly regarded for its realism and acute observation of the sitter's minute details; the man sports a light beard of one or two days' growth, a recurring feature in van Eyck's early male portraits, where subjects often appear either unshaven or, as art historian Lorne Campbell notes, "rather inefficiently shaved." Campbell identifies other unshaven sitters in van Eyck's work, including Niccolò Albergati (1431), Jodocus Vijdt (1432), Jan van Eyck? (1433), Joris van der Paele (c. 1434-1436), Nicolas Rolin (1435), and Jan de Leeuw (1436).

Notes found on the reverse of his paper study for the Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Albergati offer a glimpse into van Eyck's meticulous approach to detailing his sitters' faces. Regarding beard growth, he wrote, "die stoppelen vanden barde wal grijsachtig" (the stubble of the beard grizzled). On other aspects of his efforts to capture the old man's face, he observed, "the iris of the eye, near the back of the pupil, brownish yellow. On the contours next to the white, bluish... the white also yellowish..."

The Léal Souvenir portrait of 1432 maintains van Eyck's adherence to realism and keen observation of minute details in the sitter's appearance. However, in his later works, the sitter is often positioned at a greater distance, and the attention to detail becomes less pronounced. The descriptions shift from a forensic level to a more generalized overview, with forms appearing broader and flatter. Even in his early works, van Eyck's depictions of his models were not always faithful reproductions; he sometimes altered aspects of the sitters' faces or forms to achieve a more aesthetically pleasing composition or to align with an ideal. For instance, in the portrait of his wife, he subtly adjusted the angle of her nose and endowed her with a fashionably high forehead that she did not naturally possess, demonstrating his willingness to subtly distort reality for artistic effect.

The stone parapet at the base of the canvas in Léal Souvenir is painted with such illusionistic skill that it appears to simulate marked or scarred stone. It features three distinct layers of inscriptions, each rendered to give the impression of being chiseled directly into the stone. Van Eyck often presented these inscriptions as if spoken by the sitters themselves, making them "appear to be speaking." Notable examples include the Portrait of Jan de Leeuw, which reads: "...Jan de [Leeuw], who first opened his eyes on the Feast of St Ursula [October 21], 1401. Now Jan van Eyck has painted me, you can see when he began it. 1436." Similarly, in the Portrait of Margaret van Eyck of 1439, the lettering proclaims: "My husband Johannes completed me in the year 1439 on 17 June, at the age of 33. As I can."

Hands hold particular significance in van Eyck's paintings. In his early portraits, sitters are often depicted holding objects that denote their profession. The man in Léal Souvenir, for example, holds a scroll resembling a legal document, suggesting he may have been a legal professional. The Arnolfini Portrait (1432) is richly imbued with illusionism and symbolism, as is the 1435 Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, which was commissioned to prominently display Nicolas Rolin's power, influence, and piety.

3.2. Workshop, unfinished or lost works

Members of Jan van Eyck's workshop continued to complete works based on his designs in the years following his death in the summer of 1441. This practice was common at the time, with the widow of a master often continuing the business after his demise. It is believed that either his wife Margaret or his brother Lambert took over the management of the workshop after 1441. Such works completed by his workshop include the Ince Hall Madonna, Saint Jerome in His Study, and a Madonna of Jan Vos (also known as Virgin and Child with St Barbara and Elizabeth) from around 1443. Several of van Eyck's designs were also reproduced by leading second-generation Netherlandish artists, including Petrus Christus, who painted his own version of the Exeter Madonna.

Workshop members also undertook the task of finishing paintings that Jan van Eyck left incomplete at the time of his death. The upper portions of the right-hand panel of the Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych are generally considered to be the work of a less skilled painter with a less individual style, suggesting that van Eyck died leaving the panel unfinished but with completed underdrawings, and the upper section was subsequently completed by members or followers from his workshop.

Three works confidently attributed to van Eyck are known solely through copies. His Portrait of Isabella of Portugal dates to his 1428 visit to Portugal, where he was tasked by Philip the Good to draw up a preliminary marriage agreement with the daughter of John I of Portugal. From the surviving copies, it can be deduced that, in addition to the actual oak frame, there were two "painted-on" frames, one of which featured a Gothic inscription at the top, while a faux stone parapet provided a resting place for her hands.

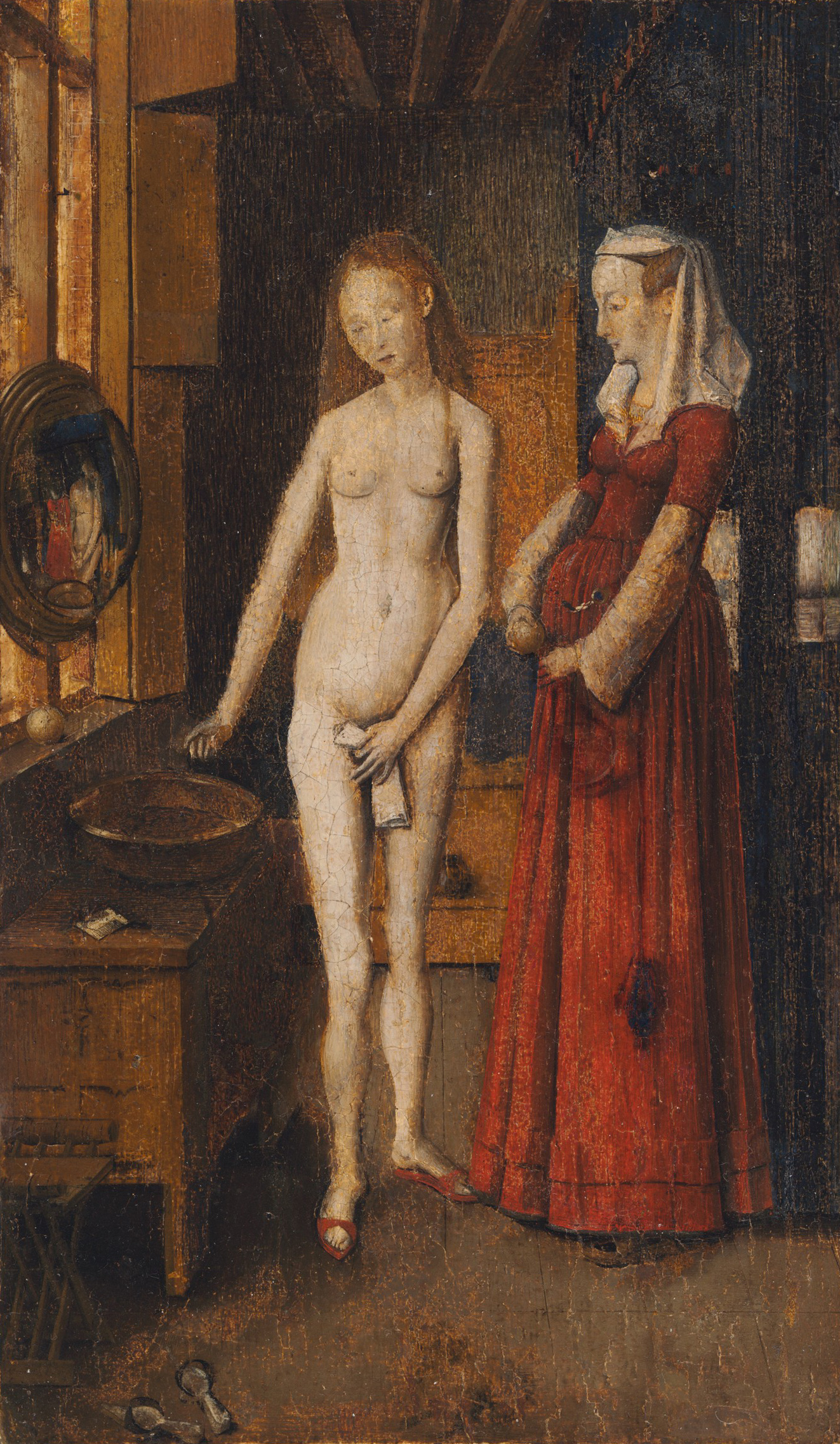

Two extant copies of his Woman Bathing were made within 60 years of his death. The original work is primarily known through its appearance in Willem van Haecht's expansive 1628 painting, The Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, which depicts a collector's gallery showcasing many other identifiable old masters. Woman Bathing shares numerous similarities with the Arnolfini Portrait, including an interior setting with a bed, a small dog, a mirror and its reflection, a chest of drawers, and clogs on the floor. More broadly, the attendant woman's dress, the contour of her figure, and the angle from which she faces are also similar.

4. Style and techniques

Jan van Eyck's distinctive style was characterized by his revolutionary mastery of oil painting, intricate iconography, and a unique approach to personal branding through signatures and innovative frame designs.

4.1. Oil painting techniques

Jan van Eyck achieved an unprecedented level of virtuosity through his groundbreaking developments in the use of oil paint. His revolutionary approach to the medium was so impactful that a widespread myth, perpetuated by 16th-century Italian biographer Giorgio Vasari and later by Karel van Mander, arose claiming that he had invented oil painting. However, the use of oil as a binding medium for pigments in painting wood statues and other objects was much older, with detailed instructions appearing in Theophilus Presbyter's 1125 treatise, On Divers Arts. Despite this, the van Eyck brothers are recognized as among the earliest Early Netherlandish painters to extensively employ oil for detailed panel paintings, and they undeniably achieved novel and unforeseen effects through their innovative application of glazes, wet-on-wet techniques, and other methods. Van Eyck's mastery of oil paints allowed for a meticulous attention to detail and the creation of luminous, intense colors and tones through the application of multiple layers of thin, translucent glazes. These advancements contributed significantly to a heightened emphasis on naturalism and realism in his work, swiftly surpassing the conventions of the International Gothic style.

4.2. Iconography and symbolism

Jan van Eyck meticulously incorporated a wide array of iconographic elements into his paintings, frequently conveying what he perceived as a harmonious coexistence of the spiritual and material worlds. His iconography was seamlessly integrated, often consisting of small yet crucial background details. This sophisticated use of symbolism and biblical references is a hallmark of his work, a handling of religious iconography that he pioneered. His innovations were subsequently adopted and further developed by artists such as van der Weyden, Memling, and Petrus Christus, all of whom employed rich and complex iconographical elements to evoke a heightened sense of contemporary beliefs and spiritual ideals.

Craig Harbison describes the masterful blending of realism and symbolism in van Eyck's work as "perhaps the most important aspect of early Flemish art." The embedded symbols were intended to merge unobtrusively into the scenes, serving as "a deliberate strategy to create an experience of spiritual revelation." Van Eyck's religious paintings, in particular, consistently "present the spectator with a transfigured view of visible reality." For him, the mundane was harmoniously steeped in symbolism, such that, according to Harbison, "descriptive data were rearranged... so that they illustrated not earthly existence but what he considered supernatural truth." This fusion of the earthly and heavenly underscores van Eyck's conviction that the "essential truth of Christian doctrine" could be found in "the marriage of secular and sacred worlds, of reality and symbol." He notably depicted unusually large Madonnas, whose unrealistic scale visually emphasized the separation between the heavenly and earthly realms, yet he placed them within relatable, everyday settings such as churches, domestic chambers, or seated alongside court officials.

Despite their earthly settings, van Eyck's churches are richly adorned with celestial symbols. A heavenly throne is clearly represented even within some domestic interiors, as seen in the Lucca Madonna. More subtly, the settings for paintings like Madonna of Chancellor Rolin represent a sophisticated fusion of the earthly and celestial. Van Eyck's iconography is often so densely and intricately layered that a single work may require multiple viewings before even the most apparent meaning of an element becomes clear. The symbols were frequently subtly woven into the compositions, becoming discernible only after close and repeated scrutiny. Much of this iconography reflects the profound idea, as articulated by John Ward, of a "promised passage from sin and death to salvation and rebirth."

4.3. Signature and motto

Jan van Eyck holds the distinct recognition as the only 15th-century Netherlandish painter known to consistently sign his panels. His unique motto invariably featured variations of the words ALS ICH KAN (or its variants like AAE IXH XAN in Greek lettering), which translates to "As I Can" or "As Best I Can." This motto cleverly forms a pun on his name. The aspirated "ICH" in his signature, as opposed to the Brabantian "IK," is derived from his native Limburgish. The word Kan itself originates from the Middle Dutch word kunnen, which is related to the Dutch word kunst or the German Kunst (meaning "art").

While the phrase may echo a formula of modesty sometimes found in medieval literature, where writers preface their work with an apology for a perceived lack of perfection, its typical lavishness suggests it might also be a playful reference. Indeed, his motto is occasionally rendered in a manner designed to mimic Christ's monogram, IHC XPC, as seen in his c. 1440 Portrait of Christ. Furthermore, given that the signature often reads as "I, Jan van Eyck was here," it can be interpreted as a somewhat audacious assertion of both the veracity and trustworthiness of the depicted scene and the high quality of the work itself ("As I (K)Can").

This consistent habit of signing his works played a crucial role in preserving his reputation, ensuring that his attribution has not been as challenging or uncertain as for many other first-generation artists of the Early Netherlandish school. His signatures are typically executed in a decorative script, often resembling those found in legal documents, a style evident in Léal Souvenir and the Arnolfini Portrait. The latter, famously signed "Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434" ("Jan van Eyck was here 1434"), serves as a direct inscription of his presence within the painted scene.

4.4. Inscriptions and frames

Many of Jan van Eyck's paintings are richly inscribed with lettering in Greek, Latin, or vernacular Dutch. Art historian Lorne Campbell notes a "certain consistency" across many examples, suggesting that van Eyck himself painted these inscriptions rather than them being later additions. The function of these letterings appears to vary depending on the type of work on which they appear. In his single panel portraits, the inscriptions often give voice to the sitter, most notably in the Portrait of Margaret van Eyck, where the Greek lettering on the frame translates as: "My husband Johannes completed me in the year 1439 on 17 June, at the age of 33. As I can."

In contrast, the inscriptions found on his public, formal religious commissions are written from the perspective of the patron, serving to emphasize their piety, charity, and dedication to the saint with whom they are depicted. An example of this can be seen in his Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, where an inscription on the lower imitation frame refers to the donation: "Joris van der Paele, canon of this church, had this work made by painter Jan van Eyck. And he founded two chaplaincies here in the choir of the Lord. 1434. He only completed it in 1436, however."

These inscriptions serve multiple purposes: they breathe life into portraits, allowing those venerating Mary to 'speak', but they also play a functional role. Given that contemporary religious works were often commissioned for private devotion, these inscriptions may have been intended to be read as an incantation or as personalized indulgence prayers. Craig Harbison observes that van Eyck's privately commissioned works are unusually heavily inscribed with prayers, suggesting that these words may have functioned similarly to prayer tablets, or more precisely, "Prayer Wings," as seen in the London Virgin and Child triptych.

Uniquely for his era, van Eyck frequently signed and dated his frames, which were then considered an integral part of the artwork. The painting and its frame were often created together, and while the frames were constructed by craftsmen separate from the master's workshop, their work was often considered equal in skill to that of the painter. He designed and painted the frames for his single-head portraits to mimic the appearance of stone, with his signature or other inscriptions appearing as if chiseled into the faux stone surface.

These frames also served other illusionistic purposes. In the Portrait of Isabella of Portugal (known through copies), described by an inscription on the frame, Isabella's eyes gaze coyly but directly out of the painting as she rests her hands on the edge of a faux stone parapet. Through this gesture, Isabella extends her presence beyond the pictorial space and into the viewer's realm.

Many of van Eyck's original frames are now lost, known only through copies or inventory records. The London Portrait of a Man was likely one half of a double portrait or pendant. The last record of its original frames noted numerous inscriptions, though not all were original, as frames were often overpainted by later artists. The Portrait of Jan de Leeuw also retains its original frame, which is painted over to resemble bronze.

His frames are frequently heavily inscribed, serving a dual purpose: they are decorative while also providing context for the significance of the imagery, much like the function of margins in medieval manuscripts. Works such as the Dresden Triptych were typically commissioned for private devotion, and van Eyck would have expected the viewer to contemplate both text and imagery in unison. The interior panels of the small 1437 Dresden Triptych are bordered by two layers of painted bronze frames, inscribed predominantly with Latin lettering. The texts are drawn from various sources, with the central frames featuring biblical descriptions of the Assumption, while the inner wings are lined with fragments of prayers dedicated to Saint Michael and Saint Catherine.

5. Reputation and legacy

Jan van Eyck's reputation as a master painter was solidified during his lifetime through court patronage and innovative techniques, leaving a profound and lasting legacy that influenced subsequent generations of artists in the Northern Renaissance.

5.1. Contemporary assessment

The earliest significant source on Jan van Eyck is a 1454 biography included in De viris illustribus by the Genoese humanist Bartolomeo Facio. In this work, van Eyck is lauded as "the leading painter" of his era. Facio places him among the foremost artists of the early 15th century, alongside Rogier van der Weyden, Gentile da Fabriano, and Pisanello. It is particularly noteworthy that Facio displayed as much enthusiasm for Netherlandish painters as he did for Italian masters, highlighting van Eyck's international renown. Facio's text also sheds light on aspects of Jan van Eyck's output that are now lost, referencing a bathing scene owned by a prominent Italian collector, although he mistakenly attributed a world map, painted by another artist, to van Eyck.

Facio further noted that van Eyck was a well-educated individual, possessing knowledge of the classics, particularly familiar with the art theories of the ancient Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder. Evidence of his classical scholarship is also found in his works, such as phrases quoted from the Roman poet Ovid's Ars Amatoria reportedly inscribed on the original (now lost) frame of the Arnolfini Portrait, and the numerous Latin inscriptions present in many of his paintings. His travels abroad on behalf of Philip the Good may have further contributed to his linguistic and classical knowledge.

During his lifetime, van Eyck was widely recognized as a revolutionary master who transformed painting across Northern Europe. His artistic designs and methods were extensively copied and reproduced, spreading his influence rapidly. This widespread acclaim is further evidenced by records from 1437 indicating his high esteem among the upper echelons of the Burgundian nobility and his frequent engagement in foreign commissions. Philip the Good's strong appreciation for van Eyck is clearly demonstrated in a 1435 record where the Duke reprimanded his financial officers for delayed payments to the artist, emphasizing that if van Eyck were to leave the Burgundian court, no one could replace his "art and learning."

5.2. Later influence

Jan van Eyck's groundbreaking approach to oil painting was so profound that it gave rise to a widespread myth, perpetuated by Italian art historian Giorgio Vasari and later by Karel van Mander, that he had invented the medium. While historical evidence indicates that oil painting as a technique for coloring wooden statues and other objects existed long before van Eyck, and was described in works such as Theophilus Presbyter's 1125 treatise On Divers Arts, the van Eyck brothers are credited with being among the earliest Early Netherlandish painters to skillfully employ oil for detailed panel paintings. They achieved unprecedented and striking effects through their innovative use of glazes, wet-on-wet techniques, and other meticulous applications.

Van Eyck was immensely influential, and his distinctive techniques and artistic style were widely adopted, refined, and built upon by subsequent generations of Early Netherlandish painters. Unlike many of his contemporaries whose reputations waned over time, Jan van Eyck's standing as a master never diminished, and he continued to be held in high regard throughout the centuries that followed, securing his lasting place in art history.

5.3. Monuments and commemoration