1. Overview

Jacques Marquette, also known as Père MarquetteFrench (June 1, 1637 - May 18, 1675), was a French Jesuit missionary and explorer who played a pivotal role in the European understanding and colonization of North America. After his ordination as a priest, Marquette was assigned to New France, where he dedicated himself to learning Indigenous languages and cultures. His significant contributions include the establishment of some of Michigan's first European settlements, such as Sault Ste. Marie and Saint Ignace. In 1673, he, alongside French-Canadian explorer Louis Jolliet, became the first Europeans to explore and map the northern portion of the Mississippi River Valley. This expedition, driven by French colonial interests in finding a western route to the Far East, relied heavily on Indigenous knowledge and guidance. Marquette's life reflects the complex interplay of religious evangelism, geographical discovery, and the profound social and cultural exchanges that characterized the early period of European expansion into lands inhabited by diverse Indigenous peoples, often leading to both collaboration and conflict. His legacy is enduringly commemorated across North America, though the historical narrative increasingly acknowledges the perspective and impact on the Indigenous communities with whom he interacted.

2. Early Life and Background

Jacques Marquette's early life in France was characterized by a strong Jesuit education and a burgeoning desire for missionary work, which ultimately led him to the frontiers of New France.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Born in Laon, France, on June 1, 1637, Jacques Marquette was the third of six children to Rose de la Salle and Nicolas Marquette. The de la Salles were a prosperous merchant family, and the Marquette family had a long-standing reputation for service in both military and civil posts. At the tender age of nine, Jacques was sent to study at the Jesuit College in Reims, where he remained until he joined the Society of Jesus at 17. His education instilled in him a profound intellectual curiosity and spiritual devotion.

2.2. Jesuit Ordination and Early Career

Marquette entered the Society of Jesus at the age of seventeen in 1654. After his initial formation, he spent several years teaching in various Jesuit institutions across France. He taught for a year at Auxerre, then pursued philosophical studies at Pont-à-Mousson until 1659. Subsequently, he taught at Pont-à-Mousson, Reims, Charleville, and Langres until 1665. Throughout this period, Marquette repeatedly petitioned his superiors for assignment to missionary work. His request was eventually granted due to the pressing need for missionaries in New France, particularly by Father Jerome Lalemant, the superior of the Jesuit mission there, who sought individuals to work with the Iroquois Five Nations. Marquette was ordained as a priest on March 7, 1666, on the Feast of Saint Thomas of Aquinas in Toul. Just months later, on September 20, he arrived in Quebec, marking the beginning of his missionary career in North America.

3. Missionary Work

Upon his arrival in New France, Marquette immersed himself in the languages and customs of the Indigenous peoples, laying the groundwork for his extensive missionary activities in the Great Lakes region.

3.1. Assignment to New France

After arriving in Quebec in 1666, Marquette was initially assigned to the mission of Saint Michel at Sillery. This mission was considered an ideal training ground for new missionaries, as it served various peaceful and friendly Indigenous groups. During his time at Sillery, Marquette diligently studied the languages and customs of the Algonquin, Abenaki, and Iroquois peoples, with whom he frequently interacted. From Sillery, he was transferred to Trois-Rivières on the Saint Lawrence River, a bustling river town with permanent shops and taverns. Here, he assisted Father Gabriel Druillettes amidst frequent attacks from the Five Nations, which necessitated a large number of French soldiers stationed in the town. Over his two years at this mission, Marquette dedicated himself to linguistic studies, achieving fluency in six different Indigenous dialects, including Huron.

3.2. Missions in the Great Lakes Region

In 1668, Marquette's superiors redeployed him to missions further up the Saint Lawrence River and into the western Great Lakes region. That same year, he collaborated with Druillettes, Brother Louis Broeme, and Father Claude-Jean Allouez to establish a mission at Sault Ste. Marie in present-day Michigan. The missionaries worked to cultivate crops, and construct a chapel and barns. They successfully forged friendly relationships with the local Ottawa and Chippewa communities, obtaining permission to baptize many infants and dying individuals. Marquette observed that the Chippewa were exceptional businessmen and highly skilled at catching whitefish from the rapids of the St. Marys River.

The abundance of whitefish at Sault Ste. Marie attracted people from numerous tribes, including the Sioux, Cree, Miami, Potawatomi, Illinois, and Menominee, who traveled to trade. Marquette and his fellow missionaries seized these opportunities to explain their Christian faith to the visitors, hoping to inspire them to seek their own Jesuit missionary, or "Black Robe," as the Indigenous peoples referred to them. In 1669, Marquette was assigned to succeed Allouez at the La Pointe du Saint Esprit mission, while Father Claude Dablon arrived to continue and expand the missionary work at Sault Ste. Marie. Marquette embarked on the 500 mile journey to La Pointe in August, traveling by canoe along the southern shore of Lake Superior. The party faced wintry conditions, often unable to light fires at night. They arrived on September 13 and were welcomed by the Petun Huron, who, excited by the return of a "Black Robe," promptly organized a banquet.

At La Pointe, Marquette's responsibilities included missionary work among the Petun Huron and three bands of Ottawa: the Keinouche, Sinagaux, and Kiskakon. He visited and ministered to all four settlements. Believing the Kiskakon were the most receptive to Christianity, he dedicated more time to their community, even residing with families in their village.

3.3. Engagement with Indigenous Peoples

During his time at La Pointe, Marquette encountered members of the Illinois tribes, who shared information about the significant trading route of the Mississippi River. They extended an invitation for him to visit their villages, predominantly located further south, and teach their people. Marquette, eager to explore this great river, sought permission to take a leave from his missionary duties. However, an urgent matter demanded his immediate attention first.

The Hurons and Ottawa residing at La Pointe had engaged in conflict with the neighboring Lakota people. Fearing an impending attack by the Lakota, Marquette determined it was imperative to find a new location for the mission. Dablon concurred that a relocation was necessary and volunteered to find a suitable site. While some men wished to remain and fight, Marquette actively tried to avert the escalating conflict. He promised those who sought to avoid war that he would lead them to a new mission and instructed them to prepare for a move eastward.

In the spring of 1671, Marquette and his party began their journey to the new St. Ignace Mission. Their canoes were heavily laden with men, women, children, animals, and personal belongings. They navigated through Lake Superior and down to the Straits of Mackinac. The mission that Dablon had established for them was situated on Mackinac Island, where a small group of Ottawa already resided and welcomed the new arrivals. Shortly after settling, concerns about potential winter starvation arose due to scarce game and uncultivated corn. Elders approached Marquette with these worries, and he agreed with their assessment. Consequently, in the fall, the mission was moved from the island to the mainland, establishing itself at St. Ignace, Michigan.

4. Exploration of the Mississippi River

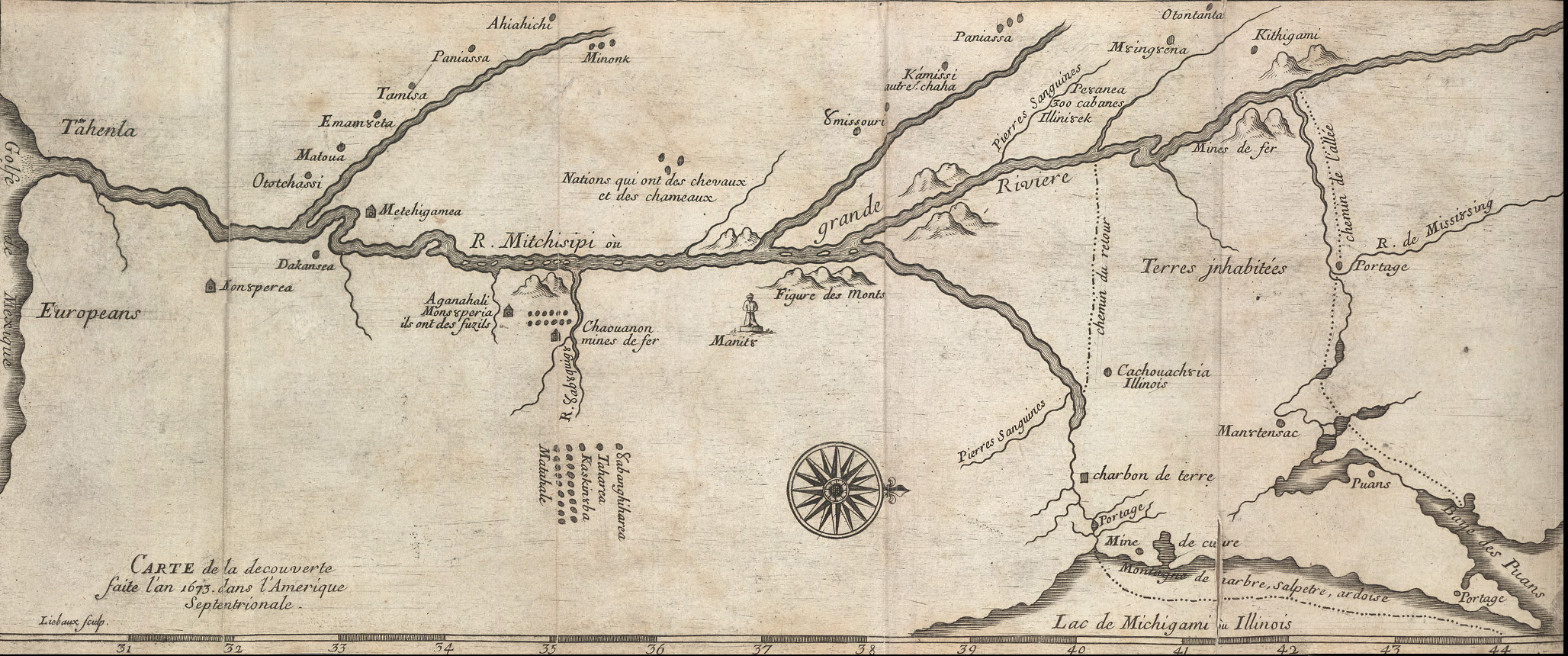

Marquette's pivotal 1673 expedition with Louis Jolliet to explore the Mississippi River marked a significant moment in the history of North American exploration, revealing new geographical insights and shaping future colonial endeavors.

4.1. Expedition Planning and Objectives

Marquette's long-held desire to explore the "great river," of which Indigenous peoples often spoke, was finally granted in 1673. He joined the expedition led by Louis Jolliet, a seasoned French-Canadian explorer. The expedition was largely driven by the French colonial interest, particularly that of Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac, in discovering a navigable water route to the Far East (Asia and the Pacific). It was believed that the Mississippi River might offer a convenient passage for traders to reach these distant lands. Marquette's fluency in several Indigenous languages was a crucial asset, making him an ideal companion for Jolliet, as communication with the various tribes encountered along the river would be essential for the expedition's success and for the potential spread of Christianity.

4.2. Journey and Discoveries

The expedition departed from Saint Ignace on May 17, 1673, with two canoes and five voyageurs of French-Indian ancestry, including Jacques Largillier, Jean Plattier, Pierre Moreau, and Jean Tiberge. Their initial route led them through Lake Huron and Lake Michigan into Green Bay. Here, they encountered the Menominee, known as the "wild rice" people. Marquette explained his mission to spread Christianity, but the Menominee attempted to dissuade the explorers, cautioning them about the perils of the river and the hostile inhabitants along its banks.

Undeterred, the group continued their journey, ascending the Fox River nearly to its headwaters. They then reached a village inhabited by the Miami, Mascouten, and Kickapoo. These communities allowed Marquette to teach them about Christianity, listening attentively. Marquette was particularly impressed by the Miami, noting their pleasant appearance and temperament despite their reputation as warriors. As the party left, two Miami accompanied them, assisting them in finding their way to the Wisconsin River. From the Fox River, the Miami guided and likely helped the men in portaging their canoes for almost 2 mile through marshlands and oak plains to the Wisconsin River. This ancient path between the two rivers would many years later become the site of Portage, Wisconsin, named for the portage itself. The expedition ventured forth from the portage and entered the Mississippi River near present-day Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, on June 17, becoming the first Europeans to enter this vast waterway. As they paddled south, the explorers observed that the river flowed in a southerly direction, leading them to conclude it emptied into the Gulf of Mexico rather than the Pacific Ocean, as some had initially hoped.

4.3. Encounters and Challenges

Eight days after entering the Mississippi, the explorers discovered footprints near the Des Moines River and decided to investigate. They were met with an enthusiastic greeting from the Peoria of the Illiniwek confederation, who lived in three small nearby villages. Marquette and his companions were warmly welcomed by the elders, offered accommodation, and treated to a banquet. The Peoria offered many gifts, but due to their travels, Marquette and the men had to decline most of them. Marquette did accept a calumet, a ceremonial pipe, gifted by the chief, who explained it symbolized peace and advised Marquette to display it as a sign of their amicable intentions. As the men prepared to leave the village, the Peoria chief cautioned them against venturing too far south.

As the party continued downstream, Marquette hoped to find the Chanouananons, a tribe known to be friendly with the French and potentially receptive to Christianity. They did not locate this tribe, but Marquette did note the presence of iron in the Wabash River area. As the summer heat intensified and mosquitoes became a significant discomfort, the men ceased going ashore at night, choosing instead to sleep in their canoes, using sails as protection from the insects. This nocturnal arrangement attracted the attention of some Native Americans who pointed guns at the travelers. Marquette, recognizing the potential for misunderstanding, held the calumet above his head. He attempted to communicate in Huron, but was unsuccessful. However, he sensed that the armed men might be inviting them to their village, which proved correct. Following them, Marquette and the others were welcomed and provided with beef and white plums.

At the mouth of the Saint Francis River, the men sighted another village. They heard war cries and observed men jumping into the river, attempting to reach their canoes. Once again, Marquette held the calumet aloft, and the elders on shore, recognizing the symbol of peace, called off the attack. The explorers were then invited into the village of the Michigamea. While one Michigamea individual was able to converse with Marquette in the Miami Illinois language, most of the communication relied on gestures. The men were fed fish and corn stew and given a place to sleep for the night. The following morning, Michigamea warriors in dugout canoes escorted them to the Quapaw people, also known as the Akansea. There, they were greeted by a group of men in canoes holding their own calumets. Marquette and his party were invited into the village, where many residents came out to see the Frenchmen. A chief led them to a gathering of elders and other chiefs. Through an interpreter, Marquette inquired about the lands further south. He was warned that the region was exceedingly dangerous, inhabited by hostile, well-armed people who would attack anyone perceived as interfering with their established trading arrangements.

4.4. Significance and Impact of the Exploration

The Jolliet-Marquette expedition had navigated to within 435 mile of the Gulf of Mexico. At this juncture, Marquette and the others deliberated whether the potential dangers outweighed the rewards of continuing. They had observed several Indigenous individuals carrying European trinkets, leading them to fear an encounter with explorers or colonists from Spain. Having meticulously mapped the areas they had traversed, documenting the local flora, wildlife, and natural resources, the party decided to conclude their exploration after staying with the Akansea for two nights.

On July 17, they turned back at the mouth of the Arkansas River. They retraced their journey up the Mississippi until they reached the mouth of the Illinois River, which local Indigenous peoples had informed them provided a shorter route back to the Great Lakes. Following this advice, they traveled via the Illinois River, then the Chicago Portage, ultimately reaching Lake Michigan near the site of modern-day Chicago. Along this return route, they encountered a village of Kaskaskia, who extended an invitation for Marquette to return and establish a mission among them. As the explorers departed the village, some Kaskaskia joined them in their canoes, accompanying them to the Saint Francis Xavier mission in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Jolliet subsequently returned to Quebec to deliver the news of their significant discoveries. The entire expedition lasted approximately five months.

This expedition profoundly advanced European geographical knowledge of North America, definitively establishing that the Mississippi River flowed south into the Gulf of Mexico, rather than westward to the Pacific. This discovery held immense geopolitical significance, opening new avenues for French colonial expansion and trade in the interior of the continent. However, the increased European presence and the establishment of new trade routes inevitably brought further impacts and changes to the lives and societies of the Indigenous communities who had long inhabited these lands.

5. Final Journey and Death

Following his momentous expedition, Marquette dedicated his remaining time to missionary work, though his health deteriorated, leading to his eventual demise and a subsequent reburial with a unique historical controversy.

5.1. Return to Illinois and Mission Founding

Marquette and his party returned to the Illinois territory in late 1674, becoming the first Europeans to spend the winter in what would later become the city of Chicago. They were welcomed as guests by the Illinois Confederation and were feasted en route, being served ceremonial foods such as sagamite. Fulfilling his promise to the Kaskaskia, Marquette established the Immaculate Conception mission for them on December 4, 1674.

5.2. Illness and Death

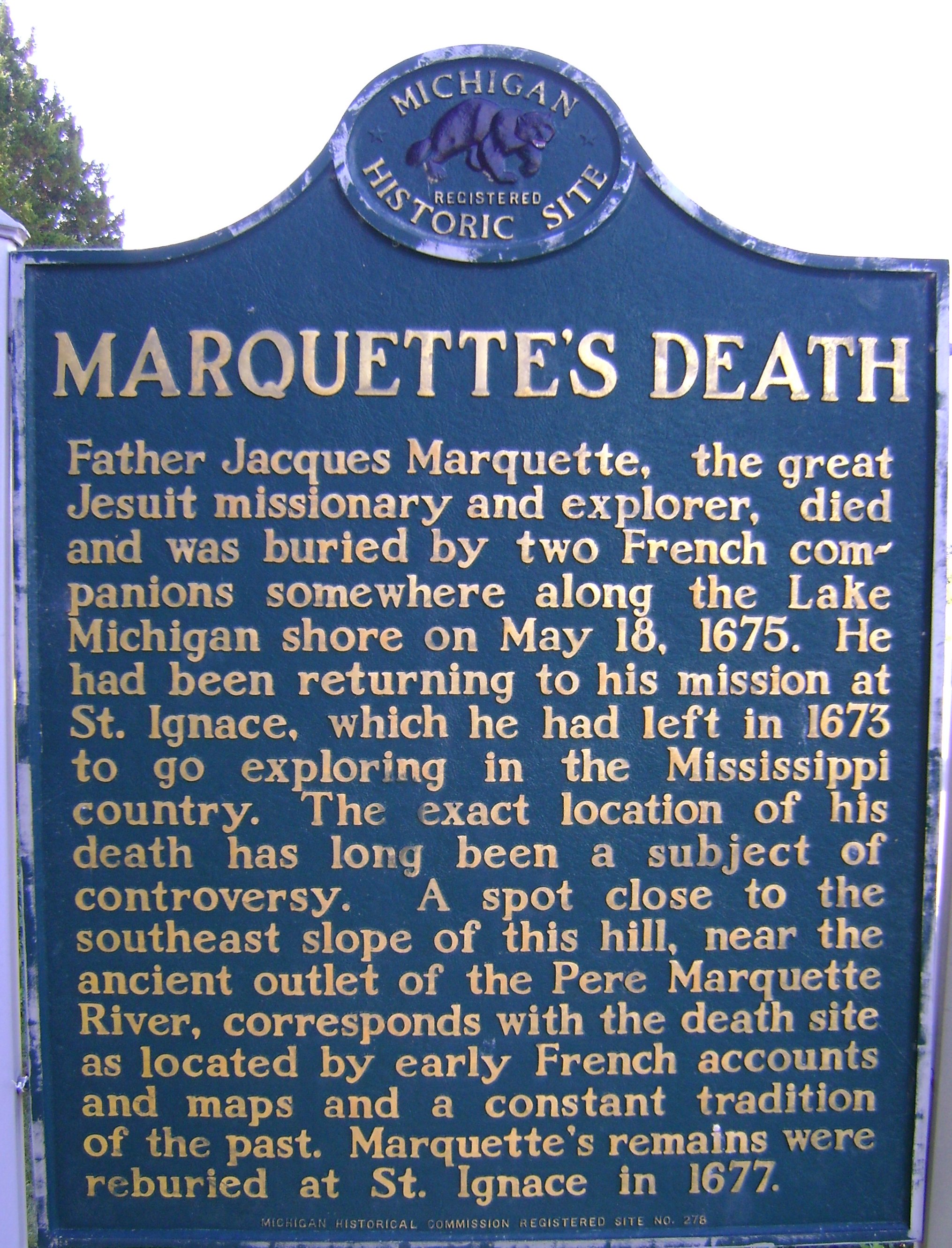

In the spring of 1675, Marquette traveled westward and celebrated a public Mass at the Grand Village of the Illinois near Starved Rock. However, his health had been severely compromised by a bout of dysentery contracted during his extensive Mississippi expedition. On his return journey to Saint Ignace, he succumbed to his illness at the age of 37, dying near the modern-day town of Ludington, Michigan, on May 18, 1675. His two companions, Pierre Porteret and Jacques Largillier, respectfully buried his body at a spot Marquette himself had chosen. They marked his burial site with a large cross before continuing their journey to St. Ignace to inform the mission of his death.

5.3. Reburial and Death Site Controversy

Two years later, in 1677, Kiskakon Ottawa from the Saint Ignace mission located Marquette's gravesite. They meticulously cleaned his bones in preparation for their journey back to the mission. A large procession of Ottawa and Huron, comprising approximately thirty canoes, accompanied the remains. Marquette's bones were presented to Fathers Nouvel and Piercon, who then led funeral services before reburying his bones in the chapel at Mission Saint-Ignace on June 9, 1677.

The precise location of Marquette's death has long been a subject of historical debate. Michigan Historical Markers offer differing perspectives on the exact location of Marquette's death. One marker in Ludington, Michigan, suggests a site near the ancient outlet of the Pere Marquette River corresponds with early French accounts and local tradition, stating he died and was buried there by his companions on May 18, 1675. Another marker in Frankfort, Michigan, while confirming his death on the same date along the Lake Michigan shore, asserts that evidence from the 1960s indicates the actual death site was near the natural outlet of the Betsie River, identifying it as the "Rivière du Père Marquette" from historical records. Both markers agree on his reburial at St. Ignace in 1677.

In 2018, residents of St. Ignace, some of whom are descendants of the Indigenous people Marquette led to the mission, became aware that an ounce of Marquette's bones was housed at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This discovery initiated discussions between the community and the university. The Museum of Ojibwe Culture subsequently sent a formal request for the return of these remains, a request that Marquette University honored. In March 2022, two Native American men, including an Anishinaabe elder, traveled to the university and were presented with Marquette's bones, which they respectfully placed in a birch box for their journey back to St. Ignace. Following a solemn ceremony, these retrieved bones were reburied with the rest of Marquette's remains on June 18, 2022. Adjacent to Marquette's gravesite on State Street in downtown Saint Ignace, a building now stands that houses the Museum of Ojibwe Culture, serving as a focal point for understanding the history and cultural connections related to Marquette and the Indigenous communities he encountered.

6. Legacy and Commemoration

The enduring legacy of Jacques Marquette is widely recognized across North America, evidenced by numerous places, institutions, and memorials named in his honor, solidifying his historical significance as both a missionary and an explorer. In the early 20th century, Marquette was broadly celebrated as a Catholic founding father of the region, a perspective that continues to inform many commemorations.

6.1. Places and Institutions Named After Marquette

Marquette's name graces various geographical locations and institutions across the United States and Canada:

- Marquette County, Michigan and Marquette County, Wisconsin.

- Several communities, including Marquette, Michigan; Marquette, Wisconsin; Marquette, Iowa; Marquette, Illinois; Marquette Heights, Illinois; Pere Marquette Charter Township, Michigan; and Marquette, Manitoba in Canada.

- Marquette University and Marquette University High School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

- Marquette Island in Lake Huron.

- Lake Marquette in Minnesota and Marquette Lake in Quebec.

- The Pere Marquette River and Pere Marquette Lake, which drain into Lake Michigan at Ludington, Michigan.

- Marquette River in Quebec.

- Various parks: Pere Marquette Park in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Pere Marquette State Park near Grafton, Illinois; Marquette Park in Chicago, Illinois; Marquette Park in Gary, Indiana; Marquette Park on Mackinac Island, Michigan; and Marquette Park in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Educational institutions such as Marquette Catholic High School in Alton, Illinois, and Marquette Academy Catholic High School in Ottawa, Illinois, and École Père-Marquette, a high school in Montreal, Quebec.

- The Hotel Pere Marquette in Peoria, Illinois.

- Pere Marquette Beach, a public beach in Muskegon, Michigan.

- Pere Marquette State Forest in Michigan.

- The Pere Marquette Railway.

- "Cité Marquette," a former US-City-Base built between 1956 and 1966 by Americans stationed at the NATO Air Force Base in Couvron, near Laon, France, his birthplace.

- Marquette Transportation Company, a towboat company that uses a silhouette of Père Marquette in his canoe as their emblem.

- Prominent buildings such as the Marquette Building in Chicago, the Marquette Building in Detroit, and the Marquette Building in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Marquette Avenue, a major street in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

6.2. Monuments, Statues, and Historical Markers

Marquette is widely commemorated through various statues, monuments, and historical markers across North America:

- The Father Marquette National Memorial is located near Saint Ignace, Michigan.

- The Chicago Portage National Historic Site, commemorating his and Louis Jolliet's journey, is situated near Lyons, Illinois.

- Statues honoring Marquette have been erected in numerous locations, including his birthplace, Laon, France.

- He is also represented by a statue in the National Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol and by a sculpture at the Quebec Parliament Building.

- The Legler Branch of the Chicago Public Library houses "Wilderness, Winter River Scene," a restored mural by Midwestern artist R. Fayerweather Babcock. This mural, commissioned in 1934 and funded by the Works Progress Administration, depicts Marquette and Native Americans engaged in trade by a river.

Beyond these major commemorations, several other statues and markers honor Marquette:

Statue of Marquette in Detroit, Michigan.

Statue of Marquette at Fort Mackinac.

Statue of Marquette in Marquette, Michigan.

Statue of Marquette in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

Pere Marquette Memorial in Utica, Illinois. - A marker commemorates Marquette's wintering location in 1674-75, which is today in Chicago.

6.3. Postal Honors and Cultural Recognition

Jacques Marquette has been honored twice on postage stamps issued by the United States:

- A one-cent stamp issued in 1898, as part of the Trans-Mississippi Issue, which depicts him on the Mississippi River. This marked the first time a Catholic priest was honored by the U.S. Postal Department.

- A six-cent stamp issued on September 20, 1968, commemorating the 300th anniversary of his establishment of the Jesuit mission at Sault Ste. Marie.

These postal honors, alongside the widespread naming of places and erection of monuments, underscore Marquette's significant place in historical narratives and popular memory in North America.