1. Early Life and Education

Ivan Wyschnegradsky's early life was marked by a strong family background and a diverse education that laid the groundwork for his unique musical path.

1.1. Birth and Family

Ivan Wyschnegradsky was born in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, on May 4, 1893. His father, Alexander, was a banker, and his mother, Sophie, was a poet. His paternal grandfather, also named Ivan Vyshnegradsky, was a renowned mathematician who served as the Minister for Finance from 1888 to 1892.

1.2. Education

After completing his baccalaureate, Wyschnegradsky initially enrolled in the School of Mathematics. He later pursued legal studies, entering the School of Law in 1912 and completing his degree in 1917, just before the Russian Revolution. Concurrently with his law studies, he dedicated himself to music, studying harmony, composition, and orchestration with Nicolas Sokolov at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory from 1911 to 1914.

1.3. Early Musical Influences

Wyschnegradsky's early musical development was profoundly shaped by the mystical and tonal explorations of Alexander Scriabin, whose works he discovered in Saint Petersburg. A pivotal moment occurred in November 1916 when he experienced a spiritual vision that inspired his oratorio, La Journée de l'Existence (The Day of Existence), a work he would continue to refine for decades and which premiered only in 1978. This singular experience became the genesis for most of his later compositions and theoretical concepts.

Although he did not attend Mikhail Matyushin's Futurist opera Victory over the Sun in 1913, the brief use of quarter-tones in its score significantly influenced his artistic direction. Wyschnegradsky became an ardent supporter of the Russian Revolution, setting Vasily Knyazev's The Red Gospel to music. In 1919, he composed incidental music for a production of Macbeth at the Tovstonogov Bolshoi Drama Theater. He quickly became convinced that equal temperament was insufficient for his musical vision and began composing in microtones, initially using two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart to achieve the desired intervals.

2. Emigration and Musical Career in Paris

Wyschnegradsky's move to Paris marked a new chapter in his life, where he continued to develop his groundbreaking musical theories and compositions.

2.1. Emigration and Settlement in Paris

In 1920, Wyschnegradsky emigrated from Soviet Russia to Paris. His primary motivation for leaving was the urgent desire to develop instruments capable of performing his microtonal compositions, as such resources were unavailable in Russia. He initially intended to return to the Soviet Union, but the country had undergone too many changes by the time he was prepared to do so a few years later. In 1922, he traveled to Berlin to meet other pioneering microtonal composers such as Richard Stein, Alois Hába, Willy Möllendorff, and Jörg Mager, to collaborate on quarter-tone piano projects. However, these plans were thwarted by technical difficulties and visa issues, forcing him to return to Paris.

2.2. Personal Life

Wyschnegradsky's personal life in Paris saw significant changes. In 1923, he married Hélène Benois, a painter and daughter of the renowned artist Alexandre Benois. Their son, Dimitri, was born in 1924 and later became an influential blues historian under the pen name Jacques Demêtre. Wyschnegradsky and Benois divorced in 1926. He later married Lucile Markov (Gayden), an American national whom he met in 1929.

During World War II, Wyschnegradsky faced severe hardships. In 1942, he was arrested by German forces and interned for two months at the Royallieu-Compiègne internment camp, while his wife Lucile was interned at Vittel. After the war, he contracted tuberculosis and spent three years, from 1947 to 1950, recovering at the sanatorium of St. Martin-du-Tertre. Lucile passed away in 1970. Wyschnegradsky's final years in his Paris apartment are often described as austere and impoverished. The American author Paul Auster fictionalized his friendship with the composer in his 1986 novel The Locked Room, depicting Wyschnegradsky by name and receiving a refrigerator from his younger friend. Wyschnegradsky died in Paris on September 29, 1979, at the age of 86.

2.3. Musical Development and Recognition

Wyschnegradsky's musical career in Paris was marked by persistent innovation and a gradual, though often delayed, recognition of his unique contributions. His first performed work, Andante religioso and funèbre, premiered in 1912, earning him praise from César Cui for its "moderation."

He dedicated himself to developing instruments for microtonal music. He designed a quarter-tone keyboard with three manuals. In 1921, Pleyel manufactured a quarter-tone piano for him that utilized their pneumatic Pleyela system, but its inconsistent tone rendered it unsuitable for his compositions. However, he extensively used piano rolls to refine the complexity of his music. While in Berlin, he found more interest in quarter-tone music. He found a Straube harmonium, designed by Möllendorf with smaller keys for microtones, effective enough to purchase, but recognized that such keyboards, including those like Paul von Jankó's, limited a performer's kinetic potential.

The German piano manufacturer Grotrian-Steinweg built a prototype quarter-tone piano in 1924, though the instrument is now lost. In 1928, August Förster successfully built a three-manual quarter-tone piano based on Wyschnegradsky's design in collaboration with Hába. Wyschnegradsky acquired one of these Förster upright quarter-tone pianos in 1929 and composed on it for the remainder of his life. Despite having a suitable instrument, he often found it more practical to perform his microtonal music using ensembles of separately tuned pianos. Although Hába preferred quarter-tone music to be performed on dedicated instruments, Wyschnegradsky maintained that when two pianos of the same make are correctly tuned a quarter-tone apart, they sound like a single, unified instrument.

Despite living in Paris, Wyschnegradsky's microtonal work gained influence in Russia during the 1920s. He corresponded with Georgy Rimsky-Korsakov, grandson of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who organized performances of Wyschnegradsky's works alongside those of young Soviet composers exploring microtonality, often featuring Dmitri Shostakovich as a performer.

In 1932, Wyschnegradsky published a 24-page brochure on quarter-tones. In 1934, he composed Twenty-four Preludes in All the Tones of the Chromatic Scale Diatonized with Thirteen Sounds for two quarter-tone pianos.

His symphonic work Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra), based on Friedrich Nietzsche's sketch, began in November 1918. Originally conceived for a standard orchestra with quarter-tone clarinet, harmonium, and piano, its final form became a symphony for four pianos: two tuned to 435 Hertz and two tuned a quarter-tone higher. This work, along with several others, premiered at the Salle Pleyel on January 25, 1937. The concert was a success, leading to friendships with prominent composers such as Olivier Messiaen, Henri Dutilleux, and Claude Ballif. In October 1938, Wyschnegradsky directed the recording of the third movement of Zarathoustra.

After the war, on November 11, 1945, Wyschnegradsky organized another concert of his works at the Salle Pleyel, featuring performers who included several of Messiaen's students, such as Yvonne Loriod, Pierre Boulez, and Serge Nigg. In 1951, Boulez, Yvette Grimaud, Claude Helffer, and Ina Marika performed his Second Symphonic Fragment in Paris. In 1972, The Revue Musicale published a special issue dedicated to Ivan Wyschnegradsky and Nicolas Obouhow, indicating growing recognition of his work.

In 1977, special concerts of Wyschnegradsky's music were organized by Martine Joste at Radio France and by Bruce Mather in Canada. That same year, the composer improvised on piano for a performance by Margaret Fisher in Paris. In 1978, Alexandre Myrat conducted the premiere of La Journée de l'Existence with the Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France. Wyschnegradsky was invited to the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program but was unable to attend due to his declining health. His final commission was a string trio for Radio France, which he died before completing.

3. Theories of Microtonal Music

Wyschnegradsky's profound theoretical contributions laid the groundwork for his unique approach to microtonal music, encompassing concepts of expanded tonality and the philosophical nature of sound.

3.1. Ultrachromaticism and Microtonal Systems

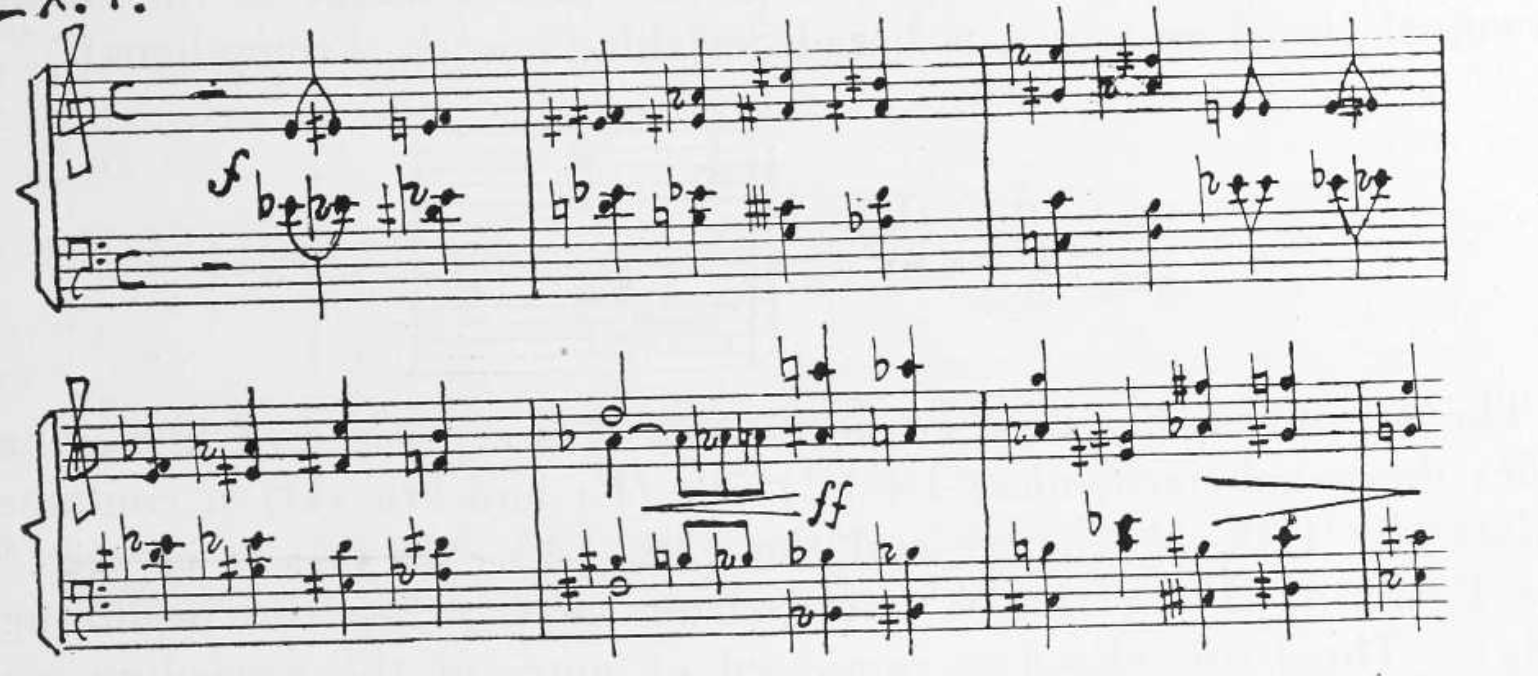

Wyschnegradsky's theoretical framework for microtonal music centered on what he termed "ultrachromaticism," the exploration of intervals smaller than the traditional semitone. While the quarter tone scale (24-equal temperament, 50 cents) was the most frequent microtonality in his compositions, he also ventured into even finer divisions of the octave. He composed a piece for Julián Carrillo's third-tone piano (18-equal temperament, 66.6 cents) and extensively used sixth tones (36-equal temperament, 33.3 cents) and twelfth tones (72-equal temperament, 16.6 cents) in his pursuit of ultrachromaticism.

3.2. Pansonority

Central to Wyschnegradsky's musical philosophy was the concept of "pansonority," which he developed from a mystical experience in 1916. He believed that music, as commonly understood, represented a separation of individual sounds from a continuous, living sonic fabric that pervades the universe. In 1927, he articulated this idea, stating that "...isolated sounds do not exist...the entire musical space is filled with living sonorous matter." He further explained that while this continuous state is "absolutely incomprehensible to human reason," it can be "clearly felt" through an "inner intuition." Wyschnegradsky viewed traditional musical art, with its reliance on discrete, detached sounds, as "artificial and anti-continuous," leading to the "primordial tragedy of music: the impossibility of attaining its ideal: Pan-sonority." He contended that the entire history of musical art was a continuous attempt to reach this ideal.

As evidence for pansonority, Wyschnegradsky pointed to the inaccuracies in assigning traditional note names to overtones. He noted that partials such as the 11th, 13th, and 14th are often raised by an entire quarter-tone to fit into equal temperament. Since these quarter-tones occur naturally within the harmonic series, Wyschnegradsky posited that microintervals are organic and offer a richer, more natural tonal world.

His mystical vision of pansonority also extended to a correspondence with the color spectrum. In his later years, he devoted more energy to creating chromatic drawings that resembled mandalas. These drawings assigned different colors to the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale, with microtones represented by related shades. Similar to Scriabin, Wyschnegradsky envisioned combining color and sound, imagining these chromatic drawings as projections on a dome above the audience during performances.

3.3. Instrumental and Technical Innovations

Wyschnegradsky's theoretical pursuits were closely intertwined with his efforts to develop and adapt musical instruments for microtonal performance. He designed a quarter-tone keyboard featuring three manuals to facilitate the playing of his complex microtonal compositions. While Pleyel manufactured a quarter-tone piano for him in 1921, its pneumatic system resulted in inconsistent tone, making it less than ideal.

His collaboration with Alois Hába and Willy Möllendorff in Berlin and Braunschweig led to discussions with Grotrian-Steinweg regarding a quarter-tone piano. Although Möllendorf designed a Straube harmonium with smaller keys for microtones, which Wyschnegradsky purchased, he recognized that such keyboards did not offer sufficient kinetic potential for performers. Grotrian-Steinweg produced a prototype in 1924, but it was August Förster who, in 1928, successfully built a quarter-tone piano based on Wyschnegradsky's design. This instrument was delivered to Wyschnegradsky's Paris apartment in 1929, becoming his primary compositional tool for the rest of his life. Despite the availability of dedicated quarter-tone instruments, Wyschnegradsky often found performing his music more feasible with ensembles of separately tuned pianos, arguing that two properly tuned pianos could sound as a single instrument.

4. Major Works

Wyschnegradsky's extensive body of work primarily consists of chamber and instrumental pieces, often for multiple pianos, reflecting his practical approach to realizing microtonal compositions.

4.1. Orchestral and Vocal Works

- La Journée de l'existence (1916-1917, revised 1927 & 1939): An oratorio for recitation, orchestra, and choir, which premiered in 1978. Its conclusion features a 12-tone tone cluster spanning five octaves.

- Variations sans thème et conclusion, Op. 33 (1951-1952): For orchestra, utilizing quarter-tones.

- Polyphonies spatiales, Op. 39 (1956): A work for piano, harmonium, Ondes Martenot, percussion, and string orchestra, employing quarter-tones.

- L'Éternel Étranger, Op. 50 (1940-1960): For voices, mixed choir, four quarter-tone pianos, percussion, and orchestra (orchestration unfinished).

- Symphonie en un mouvement, Op. 51b (1969): A one-movement symphony for orchestra, featuring quarter-tones.

- L'automne, Op. 1 (1917): A song for bass-baritone and piano, with words by Friedrich Nietzsche.

- Le soleil décline, Op. 3 (1917-1918): Another song for bass-baritone and piano, also with words by Nietzsche.

- Le scintillement des étoiles, Op. 4 (1918): For soprano and piano, with words by Sophie Wyschnegradsky (his mother).

- L'Évangile Rouge (The Red Gospel), Op. 8 (1918-1920): A song cycle for voice and piano (first version), later revised for voice and two quarter-tone pianos (second version).

- Chants sur Nietzsche (2), Op. 9 (1923): Two songs for baritone and two quarter-tone pianos.

- À Richard Wagner, Op. 26 (1934): For baritone and two quarter-tone pianos.

- Chants russes (2), Op. 29 (1940-1941): Two Russian songs for bass-baritone and two quarter-tone pianos.

- Le mot, Op. 36 (1953): For soprano and piano.

- Chœurs (2, words by A. Pomorsky), Op. 14 (1926): Two choral works for mixed choir, four quarter-tone pianos, and percussion.

- Linnite, Op. 25 (1937): A pantomime in one act and five scenes, for three voices and four quarter-tone pianos.

- Acte chorégraphique, Op. 27 (1937-1940): For bass-baritone, mixed choir, four quarter-tone pianos, percussion, and optional instruments including viola, clarinet in C, and balalaika.

4.2. Keyboard and Chamber Works

- Préludes (2), Op. 2 (1916): Two preludes for piano.

- Quatre fragments, Op. 5 (1918): Four fragments for piano (first version), later revised for two quarter-tone pianos (second version).

- Prélude et fugue sur un chant de l'Évangile rouge, Op. 15 (1927): For quarter-tone piano, with a lost version for string quartet.

- Prélude, Op. 38a (1956): A prelude for piano.

- Étude sur le carré magique sonore, Op. 40 (1956): An etude for piano.

- Étude ultrachromatique, Op. 42 (1959): For the Fokker 31-tone organ.

- Prélude et danse, Op. 48 (1966): For Julián Carrillo's third-tone piano.

- Deux piéces, Op. 44b (1958): Two pieces for Carrillo's twelfth-tone piano.

- Trauergesang, Epigrammen, Ein Stück (undated): Pieces for quarter-tone piano, discovered in Alois Hába's archives.

- Chant douloureux et étude, Op. 6 (1918): For violin and piano, employing mixed microtones.

- Méditation sur deux thèmes de la Journée de l'existence, Op. 7 (1918-1919): For cello and piano, using mixed microtones.

- Variations sur la note Do, Op. 10 (1918-1920): Variations for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Dithyrambe, Op. 12 (1923-1924, revised by Bruce Mather, 1991): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- String Quartet #1, Op. 13 (1923-1924): A quarter-tone string quartet.

- Prélude et danse, Op. 16 (1926): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- Chant nocturne, Op. 11 (1927, revised 1971): For violin and two quarter-tone pianos, using mixed microtones.

- Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra), Op. 17 (1929-1930, revised 1936): A symphony for four quarter-tone pianos, with sketches for orchestration held in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

- String Quartet #2, Op. 18 (1930-1931): Another quarter-tone string quartet.

- Études de concert (2), Op. 19 (1931): Two concert etudes for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Étude en forme de scherzo, Op. 20 (1931): An etude in the form of a scherzo for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Prélude et fugue, Op. 21 (1932): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- Pièces (2) (1934): Two pieces for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Préludes dans tous les tons de l'échelle chromatique diatonisée à 13 sons (24), Op. 22 (1934, revised 1960): 24 preludes for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Premier fragment symphonique, Op. 23a (1934): For four quarter-tone pianos; Op. 23c (1967): An orchestral version.

- Deuxième fragment symphonique, Op. 24 (1937): For four quarter-tone pianos, timpani, and percussion.

- Poème (1937): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- Cosmos, Op. 28 (1939-1940): For four quarter-tone pianos.

- String Quartet #3, Op. 38b (1945-1958): A string quartet composed with traditional tuning.

- Prélude et fugue, Op. 30 (1945): For three sixth-tone pianos.

- Troisième fragment symphonique, Op. 31 (1946): For four quarter-tone pianos and optional percussion.

- Fugues (2), Op. 32 (1951): Two fugues for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Transparence I, Op. 35 (1953): For Onde Martenot and two quarter-tone pianos.

- Arc-en-ciel (Rainbow), Op. 37 (1956): For six twelfth-tone pianos.

- Études sur les densités et les volumes, Op. 39b (1956): Etudes for two quarter-tone pianos.

- Quatrième fragment symphonique, Op. 38c (1956): For four Ondes Martenot and four quarter-tone pianos.

- Poème, Op. 44a (1958): For Carrillo's sixth-tone piano.

- Dialogue (1959): For two quarter-tone pianos, eight hands.

- Sonate en un mouvement, Op. 34 (1945-1959): A one-movement sonata for viola and two quarter-tone pianos.

- Composition en quarts de ton for string quartet Op. 43 (1960): A quarter-tone composition for string quartet.

- Composition II, Op. 46b (1960): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- Études sur les mouvements rotatoires, Op. 45b (1961): For three sixth-tone pianos and orchestra.

- Composition I, Op. 46a (1961): For three sixth-tone pianos.

- Études sur les mouvements rotatoires, Op. 45a (1961): For two quarter-tone pianos, eight hands; Op. 45c (1961): For chamber orchestra.

- Intégrations, Op. 49 (1962): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- Transparence II, Op. 47 (1962-1963): For Onde Martenot and two quarter-tone pianos.

- Composition, Op. 52 (1963): For Ondes Martenot quartet.

- Dialogue à deux, Op. 41 (1958-1973): For two quarter-tone pianos.

- Dialogue à trois, Op. 51 (1973-1974): For three sixth-tone pianos.

- Méditations (2) (undated): Two meditations for three sixth-tone pianos.

- Œuvre sans titre (undated): An untitled work for three sixth-tone pianos and a quarter-tone piano.

- String Trio, Op. 53 (1979): A quarter-tone string trio, left unfinished at his death and completed by Claude Ballif.

5. Theoretical Writings

Wyschnegradsky extensively documented his musical philosophy and microtonal theories in numerous articles and treatises throughout his career.

5.1. Major Treatises and Articles

- La Loi de la Pansonorité (The Law of Pansonority): A major treatise on microtonality that Wyschnegradsky worked on for decades but was not published during his lifetime. It was eventually published in 1996.

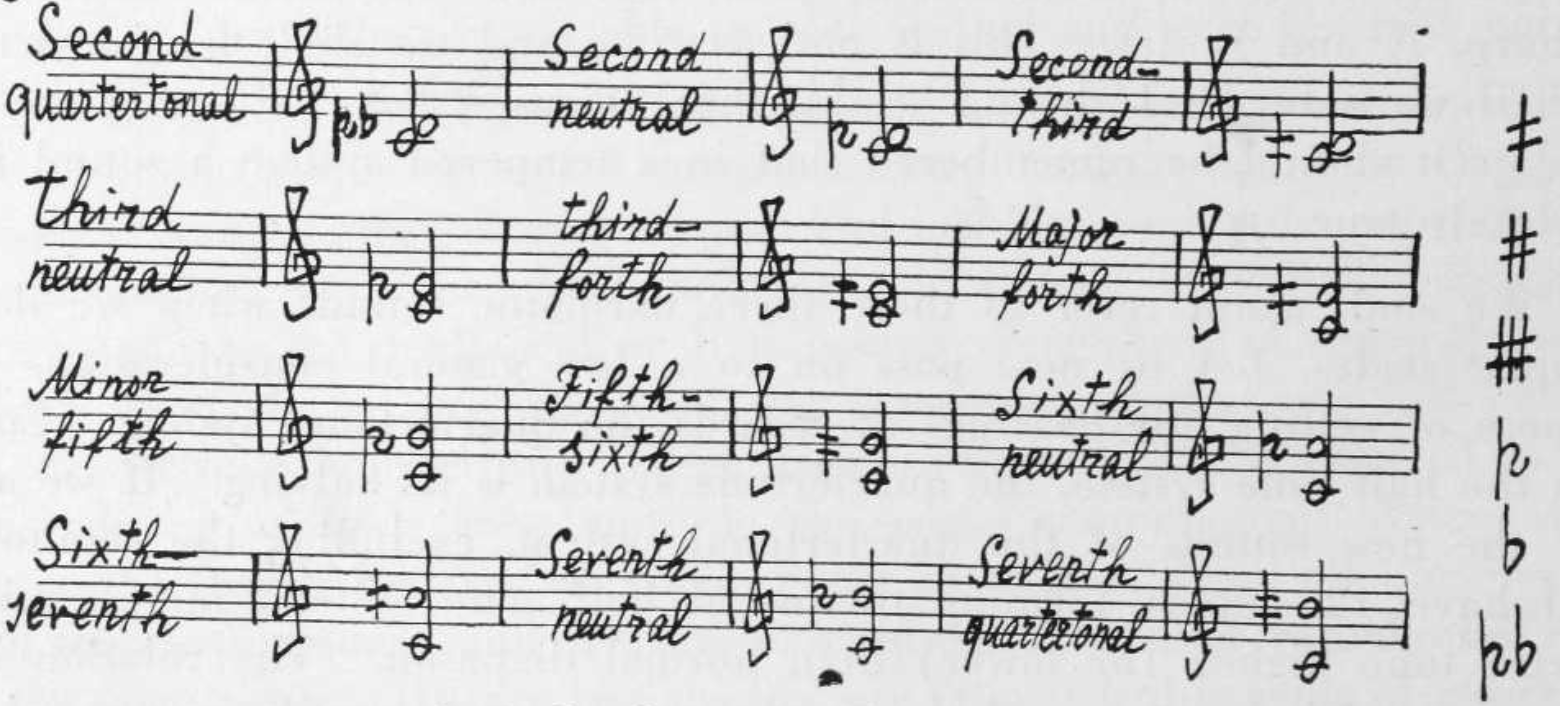

- Manuel d'harmonie à quarts de ton (Manual of Quarter-Tone Harmony) (Paris: La Sirène Musical, 1932): A methodical brochure that systematized microintervals, advancing the field beyond previous writings by composers like Charles Ives and Alois Hába. It introduced idiosyncratic names for intervals; for instance, a major third lowered by a quarter-tone is called "neutral," and a perfect fourth raised by a quarter-tone is called "major." This manual has been translated into English by Ivor Darreg and Rosalie Kaplan.

- Une philosophie dialectique de l'art musical (A Dialectical Philosophy of Musical Art) (Manuscript, 1936), published in 2005.

- Libération Du Son : Écrits 1916-1979 (Liberation of Sound: Writings 1916-1979), published in 2013.

- Other significant articles include:

- "Liberation of sound" (in Russian), Nakanune, Berlin, January 7, 1923.

- "Раскрепощение ритма" (Liberation of rhythm), Nakanune, Berlin, March 18 & 25, 1923.

- "Quelques considérations sur l'emploi des quarts de ton en musique" (Some Considerations on the Use of Quarter Tones in Music), Le monde musical, Paris, June 30, 1927.

- "Quartertonal music, its possibilities and organic Sources", Pro-Musica Quarterly, New York, October 19, 1927.

- "Musique et Pansonorité" (Music and Pansonority), La revue Musicale IX, Paris, December 1927.

- "Etude sur l'harmonie par quartes superposées" (Study on Harmony by Superimposed Fourths), Le Ménestrel, April 12 & 19, 1935.

- "La musique à quarts de ton et sa réalisation pratique" (Quarter-tone Music and its Practical Realization), La Revue Musicale 171, 1937.

- "L'énigme de la musique moderne" (The Enigma of Modern Music), La Revue d'esthétique, January-March 1949 and April-June 1949.

- "Préface à un traité d'harmonie par quartes superposées" (Preface to a Treatise on Harmony by Superimposed Fourths), Polyphonie 3, 1949.

- "Problèmes d'ultrachromatisme" (Problems of Ultrachromaticism), Polyphonie 9-10, 1954.

- "Les Pianos de J. Carrillo" (The Pianos of J. Carrillo), Guide du concert et du disque, Paris, January 19, 1959.

- Continuum électronique et suppression de l'interprète (Electronic Continuum and Suppression of the Performer), Cahiers d'études de Radio Télévision, Paris, April 1958.

- "L'ultrachromatisme et les espaces non octaviants" (Ultrachromaticism and Non-Octaviant Spaces), La Revue Musicale #290-291, Paris, 1972.

6. Later Life and Hardships

Wyschnegradsky's later life was marked by significant personal challenges and a continued dedication to his art despite declining health.

6.1. Wartime Internment and Health

During World War II, Wyschnegradsky was arrested by German forces in 1942 and held for two months at the Royallieu-Compiègne internment camp in France. His wife, Lucile, an American citizen, was also interned at Vittel. Following his release and the end of the war, Wyschnegradsky contracted tuberculosis, leading to a three-year period of recovery at the sanatorium of St. Martin-du-Tertre from 1947 to 1950. This period of illness posed a significant threat to his creative output. However, upon his discharge in 1950, he was encouraged by his supporter, Olivier Messiaen, to resume his compositional work.

6.2. Later Years and Personal Life

Lucile, Wyschnegradsky's second wife, passed away in 1970. His final years, spent in his Paris apartment, are often described as austere and marked by poverty. The American novelist Paul Auster recounted his friendship with Wyschnegradsky in his 1986 novel The Locked Room, portraying the composer by name and depicting Auster providing him with a refrigerator. Wyschnegradsky's health continued to decline in his later years. He was invited to the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program in 1977 but was too ill to attend. His last commission, a string trio for Radio France, remained unfinished at the time of his death. Ivan Wyschnegradsky died in Paris on September 29, 1979, at the age of 86.

7. Musical Legacy and Reception

Ivan Wyschnegradsky is recognized as a pivotal figure in the development of microtonal music, whose theoretical and compositional innovations left a lasting impact on 20th-century avant-garde music.

7.1. Pioneering Contributions to Microtonality

Wyschnegradsky's most significant contribution lies in his pioneering role in microtonal music. He was among the first to systematically explore and theorize about intervals smaller than the semitone, developing the concept of "ultrachromaticism." His philosophical idea of "pansonority," which posited a continuous, living sonic fabric underlying all music, provided a profound conceptual basis for his microtonal explorations. He not only composed extensively in quarter-tones, sixth-tones, and twelfth-tones but also actively engaged in the design and development of instruments capable of performing these intricate divisions, such as his three-manual quarter-tone keyboard and collaborations with piano manufacturers like August Förster. His work influenced subsequent composers and theorists, particularly within the avant-garde circles of the 20th century.

7.2. Critical Reception and Contemporary Standing

Despite his groundbreaking work, Wyschnegradsky's compositions did not gain widespread attention until later in his life. His early microtonal works, often deemed unperformable by traditional means, were ahead of their time. However, his influence began to grow, particularly in Russia during the 1920s through collaborations with figures like Georgy Rimsky-Korsakov and performances featuring Dmitri Shostakovich.

The success of his 1937 concert at the Salle Pleyel, which fostered friendships with Olivier Messiaen, Henri Dutilleux, and Claude Ballif, marked a turning point in his recognition. Further performances, including those by Messiaen's students like Pierre Boulez and Yvonne Loriod, helped bring his music to a wider audience. The publication of a special issue on Wyschnegradsky in The Revue Musicale in 1972 and large-scale concerts organized by Radio France in 1977 underscored his growing critical standing. Today, Wyschnegradsky is regarded as an important figure in 20th-century avant-garde music, whose theoretical insights and innovative compositions continue to be studied and performed, solidifying his place as a visionary in the history of microtonality.

8. Discography

- Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Ainsi Parlait Zarathoustra (third movement), op. 17. L'Oiseau-Lyre Editions, 1938.

- Mather-Lepage. Piano Duo. McGill University Records 77002. 1977. Includes Concert Etude Nos. 1 & 2, op. 19; Fugue Nos. 1 & 2, op. 33; Integration Nos. 1 &2, op. 49.

- Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Vierteltonmusik. Editions Block, Berlin, 2 LP, EB 107/108. 1983. Includes Nr. 14,16,17,18,19 from 24 Préludes Dans Tous Les Tons De L'Échelle Chromatique Diatonisée À 13 Sons, op. 22; Prélude Et Étude, op. 48; Étude Sur Les Mouvements Rotatoires, op. 45; Méditation Sur 2 Thèmes De La Journée De L'Existence, op. 7; Étude Sur Le Carré Magique Sonore, op. 40; Prélude Et Fugue, op. 21; Troisième Fragment Symphonique, op. 32; Interview with composer.

- Music for Three Pianos in Sixths of Tones. McGill University Records, 83017. 1985. Includes Dialogue à trois op. 51; Composition op. 46, no. 1; Prélude et Fugue, op. 30.

- Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Vingt-quatre Préludes opus 22, Intégrations opus 49. Fontec records, FOCD 3216. 1988.

- Arditti String Quartet. Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Edition Block, Berlin, CD-EB 201. 1990. Includes String Quartet # 1-3, op. 13, 18, 38bis; Composition for String Quartet, op. 43; Trio for strings, op. 53.

- American Festival Of Microtonal Music Ensemble. Between The Keys: Microtonal Masterpieces Of The 20th Century. Newport Classic, NPD 85526. 1992. Includes Meditation On Two Themes From The Day Of Existence, Op. 7, transcribed for bassoon and piano by Johnny Reinhard.

- Hommage à Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Société Nouvelle d'Enregistrement, SNE-589-CD. 1994. Includes Transparencies I & II; 3 Compositions en quarts de ton; Cosmos.

- Martin Gelland/Lennart Wallin. Lyrische Aspekte unseres Jahrhundert. Vienna Modern Masters, VMM 2017. 1995. Includes Chant Douloureux Für Violine Und Klavier, op. 6; Chant Nocturne Für Violine Und 2 Klaviere Im Vierteltonabstand.

- 25 Jaar Nieuwe Muziek In Zeeland. BV Haast Records/Nieuwe Muziek, CD 9501/02. 1995. Includes Ainsi Parlait Zarathoustra, op. 17.

- Acte Choreographique Opus 27. Mikroton, 1999.

- Wyschnegradsky. 2e2m Collection 1001, 1995. Includes Etudes Sur les Mouvements Rotatoires, op. 45c' Sonate, op. 34; Dialogue; Etudes sur les Densités et les Volumes, op. 39bis; Deux Chants sur Nietzsche, op. 9; Dithyrambe, op. 12.

- 50 Jaar Stichting Huygens-Fokker. Stichting Huygens-Fokker, 1999. Includes Etude Ultrachromatique pour l'orgue tricesimoprimal, op.42.

- Ivan Wyschnegradsky/Bruce Mather. L'Evangile rouge (The Red Gospel). Société Nouvelle d'Enregistrement, SNE-647-CD. 1999. Includes L'Evangile Rouge, op. 8; Deux Chants sur Nietzsche, op. 9; Deux Chants Russes, op. 29; À Richard Wagner, op. 26.

- Etude Sur Les Mouvements Rotatoires/24 Préludes. Col Legno, 20206. 2002. Includes Etude Sur Les Mouvements Rotatoires, op. 45a; 24 Préludes Dans L'Échelle Chromatique Diatonisée À 13 Sons, op. 22.

- Quarter-Tone Pieces. hat[now]ART 143, 2006. Includes Preludes In Quarter-Tone System (excerpts); Etude Sur Le "Carré Magique Sonore", op. 40.

- La Journée de l'existence. Shiiin, 4. 2009.

- Thomas Günther. Klavierwerke Um Den Russischen Futurismus Vol. 1. Cybele, 160.404. 2009. Includes Deux Préludes Pour Piano, op. 2; Etude Sur Le Carré Magique Sonore, op. 40.

- Pianos Quart De Ton. Shiiin, 10. 2018. Includes 4e Fragment Symphonique Op.38c Pour Ondes Martenot Et 4 Pianos; Ainsi Parlait Zarathoustra, op.17; Méditation Sur Deux Thèmes De La Journée De L'Existence, op.7.

9. Bibliography

- Allende-Blin, Juan. Ein Gespräch mit Ivan Wyschnegradsky. In: Alexander Skrjabin und die Skrjabinisten, edited by Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn. Munich: Edition Text + Kritik, 1983.

- Ballif, Claude. "Ivan Wyschnegradsky: harmonie du soir". Premier Cahier Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Association Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Paris, 1985.

- Bazin, Paul. La Pansonorité d'Ivan Wyschnegradsky Et Son Héritage. Quebec: McGill University, 2020.

- Gayden, Lucile. Ivan Wyschnegradsky. Frankfurt: M.P. Belaieff, 1973.

- Gojowy, Detlef. Neue sowjetische Musik der 20er Jahre. Laaber-Verl., 1980.

- Jedrzejewski, Franck. Ivan Wyschnegradsky Et La Musique Microtonale. Universite Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, France, 2000.

- Wyschnegradsky, Ivan. Manuel d'harmonie à quarts de ton. Paris: La Sirène Musical, 1932. Reissued by Éditions Max Eschig, 1980. Translated by Ivor Darreg as Xenharmonikôn 6, Summer 1977. Translated by Rosalie Kaplan. New York: Underwolf Editions, 2017.

- Wyschnegradsky, Ivan. La Loi de la Pansonorité (Manuscript, 1953). Ed. Contrechamps, Geneva, 1996.

- Wyschnegradsky, Ivan. Une philosophie dialectique de l'art musical (Manuscript, 1936). Ed. L'Harmattan, Paris, 2005.

- Wyschnegradsky, Ivan. Libération Du Son : Écrits 1916-1979. Symétrie, 2013.

- Vichney, Dimitri. Notes sur l'évangile rouge de Ivan Wyschnegradsky, Cahier du CIREM, n° 14-15, 1990.