1. Overview

Isabelle de Charrière was a prolific writer whose diverse body of work, encompassing novels, plays, pamphlets, and musical compositions, reflects her deep engagement with the intellectual and social currents of the Enlightenment. Born into a Dutch aristocratic family, she received an unusually broad education for a woman of her time, which fostered her intellectual independence and critical perspective. Her writings often explored themes of social critique, particularly concerning the nobility and the education of women, and she became a significant voice in the discourse surrounding the French Revolution. Living primarily in Switzerland after her marriage, she maintained a unique vantage point from which to observe and comment on European society, allowing her to fill a literary void during a period of revolutionary upheaval in France.

2. Early Life

Isabelle de Charrière's early life was marked by her aristocratic upbringing and an exceptional education that cultivated her intellectual and linguistic talents, laying the foundation for her later contributions to Enlightenment thought.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Isabelle van Tuyll van Serooskerken was born on 20 October 1740, at Zuylen Castle in Zuilen, near Utrecht in the Netherlands. She was the eldest of seven children born to Diederik Jacob van Tuyll van Serooskerken (1707-1776) and Jacoba Helena de Vicq (1724-1768). Her parents were described by the Scottish author James Boswell, who was a law student in Utrecht and one of her suitors, as "one of the most ancient noblemen in the Seven Provinces" and "an Amsterdam lady, with a great deal of money." During the winter months, the family resided in their house within the city of Utrecht.

2.2. Education and Intellectual Development

Isabelle de Charrière received a much broader education than was typical for girls of her era, thanks to the liberal views of her parents. They allowed her to study subjects such as mathematics, physics, and multiple languages, including Latin, Italian, German, and English. She was by all accounts a gifted student, demonstrating remarkable aptitude.

In 1750, at the age of ten, Isabelle was sent to Geneva and traveled through Switzerland and France with her French-speaking governess, Jeanne-Louise Prevost, who served as her teacher from 1746 to 1753. After speaking exclusively French for a year, she had to relearn Dutch upon returning home to the Netherlands. However, French remained her preferred language throughout her life, which contributed to her works being less known in her native country for a considerable period.

Her interest in music was lifelong; in 1790, she began studying with the renowned composer Niccolò Zingarelli. At the age of 14, she developed an unrequited affection for the Roman Catholic Polish count Peter Dönhoff. This disappointment led her to leave Utrecht for 18 months. As she matured, she rejected various suitors, either because they failed to follow through on promises to visit or because they withdrew due to her intellectual superiority. She viewed marriage as a potential path to freedom but also desired a union based on love. In 1766, Isabelle traveled by boat from Hellevoetsluis to Harwich, England, on 7 November, accompanied by her brother Ditie, her maid Doortje, and her valet Vitel, specifically invited by Anne Pollexfen Drake and her husband, Lieutenant General George Eliott, to their London home in Curzon Street, Mayfair.

3. Marriage and Later Life

Isabelle de Charrière's marriage and subsequent life in Switzerland and Paris established her social context and provided new perspectives that influenced her writings, particularly her observations on societal structures and financial realities.

3.1. Marriage and Family

In 1771, Isabelle married Charles-Emmanuel de Charrière de Penthaz (1735-1808), a Swiss national born in Colombier, Neuchâtel. Charles-Emmanuel had previously served as the private tutor for her brother, Willem René, during his studies abroad from 1763 to 1766. Following their marriage, she became known as Isabelle de Charrière. The couple settled at Le Pontet in Colombier, a property purchased by Charles-Emmanuel's grandfather, Béat Louis de Muralt. They shared their home with his father, François (1697-1780), and his two unmarried sisters, Louise (1731-1810) and Henriette (1740-1814).

The Canton of Neuchâtel was at this time under the rule of Frederick the Great as prince of Neuchâtel, in a personal union with Prussia. Neuchâtel's policy of freedom of religion attracted many refugees, including notable figures such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Béat Louis de Muralt, and David Wemyss, Lord Elcho. While Isabelle was vivacious and passionate, her husband, Charles-Emmanuel, was described as a very rational, reasonable, and reserved individual who disliked excess. Despite their differing temperaments, he was known to be considerate and kind to his wife. The couple also spent significant periods in Geneva and Paris, broadening their social and intellectual horizons.

3.2. Financial Life and Colonial Interests

In 1778, Isabelle de Charrière inherited a substantial fortune, which by modern standards made her wealthy. Nearly 40% of her investments were in colonial companies such as the Dutch West India Company (WIC), the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the British East India Company, and the South Sea Company. These companies' profitability was heavily dependent on overseas slavery in plantations.

Initially, in her letters and in her novel *Trois Femmes* (Three Women, 1795-1798), Charrière's mentions of slavery were uncritical. However, a later letter (number 1894, dated 1798) reveals a shift in her perspective, where she referred to the "horrors" in the colonies, indicating she was not indifferent to the excesses of slavery. Within five years of receiving her inheritance, Isabelle de Charrière sold off 70% of her colonial investments, demonstrating a practical response to the ethical considerations of her time.

3.3. Life in Switzerland and Paris

Isabelle de Charrière's life was characterized by her residence in Colombier, Neuchâtel, and her frequent visits to major European intellectual centers, particularly Paris. In Colombier, she actively engaged with local society, establishing her salon at Le Pontet, where much of her musical work was performed within her private circle.

From 1786, she spent over a year and a half in Paris, dedicating considerable time to composing and performing harpsichord music. During this period, she frequented literary salons, notably that of Amélie Suard, where she met the influential writer Benjamin Constant. These periods in Paris were crucial for her intellectual development and for forging connections with other prominent figures of the Enlightenment. Her cosmopolitan lifestyle and intellectual milieu provided rich material for her diverse literary and musical output.

4. Correspondence and Intellectual Connections

Isabelle de Charrière maintained an extensive network of correspondents, engaging in profound intellectual exchanges with many leading figures of the Enlightenment. Her letters offer invaluable insight into her thoughts, relationships, and active participation in the era's intellectual discourse.

4.1. Major Correspondents

Isabelle de Charrière's correspondence was a central aspect of her intellectual life, connecting her with numerous prominent individuals.

In 1760, she met David-Louis Constant d'Hermenches (1722-1785), a married Swiss officer widely regarded as a Don Juan. Despite initial hesitation, her strong need for self-expression led her to overcome her scruples. After a second meeting two years later, she began an intimate and secret correspondence with him that lasted for approximately 15 years. Constant d'Hermenches became one of her most significant and influential correspondents.

The Scottish writer James Boswell frequently met her in Utrecht and at Zuylen Castle between 1763 and 1764, while he was studying law at Utrecht University. He affectionately referred to her as Zélide, a name she used in her self-portrait. Boswell became a regular correspondent for several years after he left the Netherlands to embark on his Grand Tour. He explicitly wrote to her that he was not in love with her, to which she famously replied: "We agree, because I have no talent for subordination." In 1766, after meeting her brother in Paris, Boswell sent a conditional marriage proposal to Isabelle's father, but the fathers did not agree to the union.

In 1786, Madame de Charrière met Constant d'Hermenches' nephew, the renowned writer Benjamin Constant, in Paris. Benjamin Constant subsequently visited her in Colombier on several occasions. During these visits, they collaborated on an epistolary novel, and their exchange of letters developed into a lifelong correspondence that continued until her death. She also maintained intellectually stimulating correspondences with her younger friends, Henriette L'Hardy and Isabelle Morel. From 1801 until Isabelle de Charrière's death, Huber's young stepdaughter, Therese Forster, resided with her. During the French Revolution, she also exchanged information with various French relatives regarding the unfolding events.

5. Literary Works

Isabelle de Charrière's diverse literary output, including novels, pamphlets, plays, and poems, made significant contributions to Enlightenment literature and social commentary, often reflecting her critical perspective on contemporary issues. Her most productive period occurred after she had settled in Colombier for several years. Her works frequently explored themes of religious doubt, the nature of nobility, and the education of women.

5.1. Novels and Stories

Isabelle de Charrière's novels and short stories often employed the epistolary form and served as vehicles for social critique.

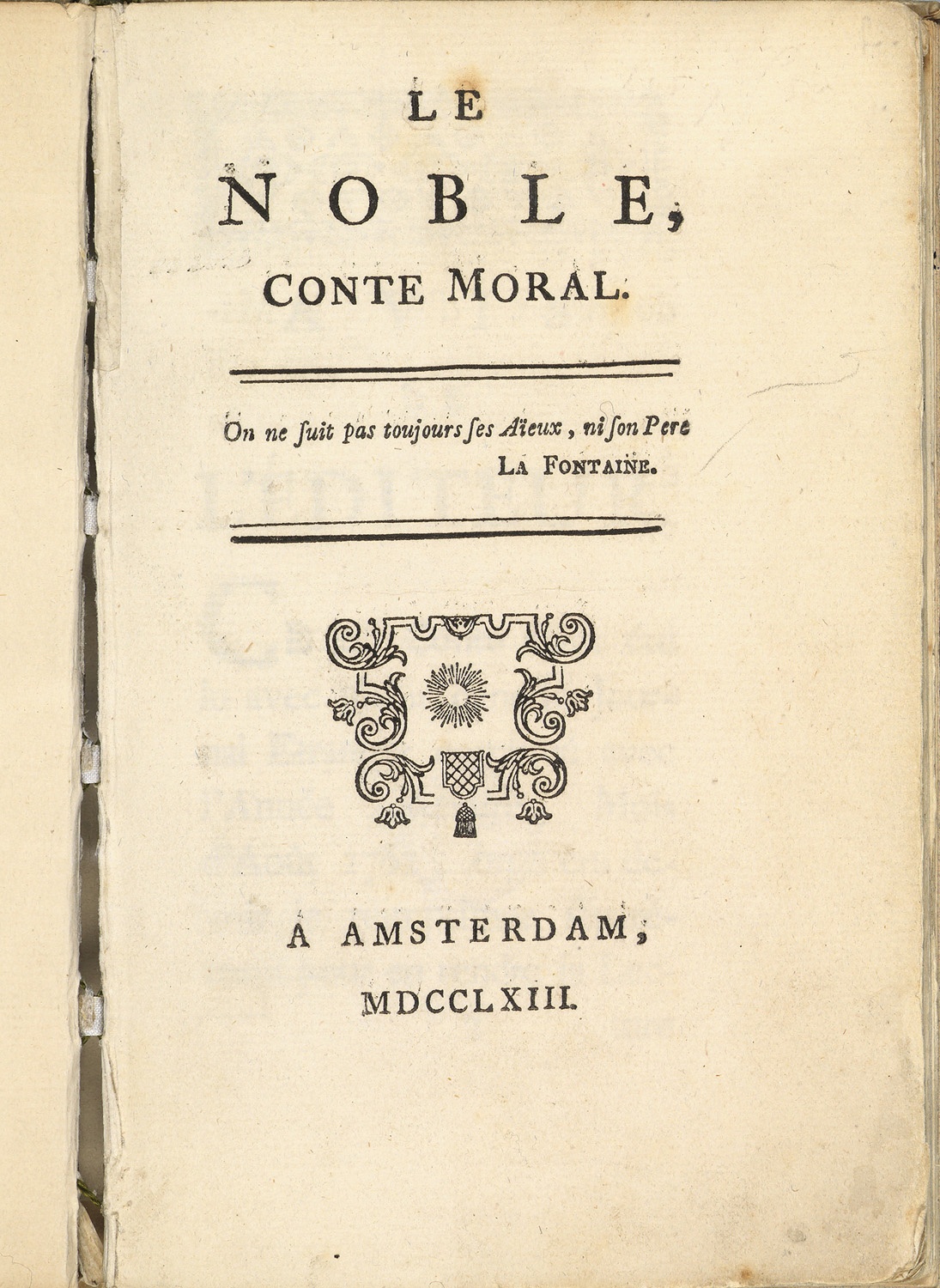

Her first novel, Le Noble (The Nobleman), was published anonymously in 1763 when she was 22 years old, appearing in a French-language magazine with the Amsterdam publisher Evert van Harrevelt. This short work was a sharp satire against the nobility, cynically criticizing those who boasted of their aristocratic status. Although published anonymously, her identity was soon discovered, leading her parents to withdraw the work from sale. Despite this, the "moral tale" found its way into Europe, notably being reviewed by the German poet and statesman Johann Wolfgang Goethe on 3 November 1772, in the "Frankfurter Gelehrten Anzeigen," following its German translation, Die Vorzüge des alten Adels. The novel opens with a quote from Jean de La Fontaine's fable Education: "We do not always follow our ancestors, nor even resemble our fathers."

She also wrote a self-portrait for her friends titled Portrait de Mll de Z., sous le nom de Zélide, fait par elle-même. 1762. In 1784, she published two fictional works: Lettres neuchâteloises (Letters from Neuchâtel) and Lettres de Mistriss Henley publiées par son amie (Letters from Mistress Henley published by her friend). Both were epistolary novels, a form she continued to favor. The Korean source notes that reading the Dutch novel Sara Burgerhart (1782) inspired her to understand that novels could gain realism by depicting familiar places and customs. Consequently, she set Lettres neuchâteloises in the city where she lived. While Letters de Mistress Henley is set in England, its content is not particularly English, and the character of Mr. Henley bears a resemblance to her own husband.

Encouraged by the success of these early works, she wrote Lettres écrites de Lausanne (Letters written from Lausanne, 1785) and its sequel, Caliste ou continuation de Lettres écrites de Lausanne (Caliste or continuation of Letters written from Lausanne, 1787), set in the nearby city of Lausanne. These works are still considered among her most representative. Other notable novels and stories include Bien-né. Nouvelles et anecdotes. Apologie de la flatterie (1788), Trois femmes (1795), Honorine d'Userche : nouvelle de l'Abbé de La Tour (1795), Sainte Anne (1799), and Sir Walter Finch et son fils William (1806), which was published posthumously.

5.2. Pamphlets and Political Commentary

Isabelle de Charrière actively engaged with the political and social issues of her time through her pamphlets and essays, offering incisive commentary on contemporary events.

In 1788, she published her first pamphlets addressing the political situations in the Netherlands, France, and Switzerland. As an admirer of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, she played a role in the posthumous publication of his Confessions in 1789. Around the same time, she also wrote her own pamphlets concerning Rousseau's ideas.

The French Revolution led many nobles to seek refuge in Neuchâtel, and Madame de Charrière befriended some of them. However, she also published works that critically examined the attitudes of these aristocratic refugees, many of whom she believed had learned nothing from the revolutionary events. Her works, such as L'émigré (The Emigrant, a three-act comedy, 1793) and Lettres trouvées dans des portefeuilles d'émigrés (Letters found in emigrants' portfolios, 1793), expressed sympathy for the plight of French noble refugees while also serving as valuable historical documents detailing their lives. Other pamphlets include Courte réplique à l'auteur d'une longue réponse ; par Mme la Baronne de ... (1789), Plainte et défense de Thérese Levasseur (1789), and Lettre à M. Necker sur son administration, écrite par lui-même (1791).

5.3. Plays and Poems

Isabelle de Charrière's creative output also extended to dramatic works and poetry, often reflecting her engagement with social and personal themes. She wrote or planned the words and music for several musical works, though not all have survived.

Her opéra-bouffe, De Deugd is den Adel waerdig (Vertu vaut bien noblesse) (Virtue is Worth Nobility), a Dutch adaptation of her novel Le Noble, was performed in the Fransche Comedie theater in The Hague on 2 March 1769. This was her only stage work performed during her lifetime, though both the libretto and music are now considered lost. She also sent a libretto for an opera titled Les Phéniciennes to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Vienna, hoping he would compose music for it, but no reply from him is known. Additionally, she wrote both the poetry and music for ten Airs et Romances.

6. Musical Compositions

Isabelle de Charrière was a talented composer, and her musical works are compiled in volume 10 of her Œuvres complètes. Her compositions include:

- Six minuets pour deux violons, alto et basse (for two violins, viola, and bass), essentially a string quartet, dedicated to Monsieur le Baron de Tuyll de Serooskerken, Seigneur de Zuylen (published in The Hague and Amsterdam by B. Hummel et fils, 1786).

- Nine sonatas for harpsichord.

- Ten Airs et Romances (published in Paris by M. Bonjour, 1788-1789), for which she composed both the poetry and the music.

Most of her musical compositions were performed within the private circle of her salon at Le Pontet. She also studied music with the composer Niccolò Zingarelli starting in 1790.

7. Views on Society and Politics

Isabelle de Charrière's writings and life reflect a deep engagement with Enlightenment philosophy and a critical perspective on the social and political issues of her time. Her work demonstrates a nuanced understanding of the era's transformative ideas.

She held a keen interest in society and politics, which permeated her literary output. Her first novel, Le Noble, was a direct satire against the aristocracy, a theme she revisited when criticizing the attitudes of the noble refugees during the French Revolution. While she initially appeared uncritical of slavery in some early mentions, her later correspondence expressed concern over the "horrors" in the colonies, leading her to divest a significant portion of her investments in colonial companies.

Charrière's commentary on the French Revolution was complex; she sympathized with the plight of the emigrant nobles but also critiqued their inability to learn from the revolutionary events. She consistently advocated for progressive social ideas, including women's education, and actively advised and supported young women through her interactions and correspondence. Her intellectual independence and critical analysis of societal structures mark her as a significant voice in the Enlightenment's pursuit of reason and reform.

8. Critical Reception and Legacy

Isabelle de Charrière's works have received varied critical attention both during her lifetime and posthumously, securing her lasting impact on literature and social thought, particularly concerning women's intellectual contributions.

8.1. Literary Assessment

During her lifetime, Isabelle de Charrière's identity as the author of Le Noble was quickly discovered, leading her parents to withdraw the satirical work from sale, though it still circulated and was reviewed by figures like Johann Wolfgang Goethe. Her later epistolary novels, such as Lettres neuchâteloises and Lettres écrites de Lausanne, were well-received and are considered her representative works.

Modern critical evaluations highlight her unique position as a female writer in the Enlightenment. Her distinctive background-being Dutch, residing in Switzerland, and writing in French-allowed her to remain somewhat detached from the direct turmoil of the French Revolution. This distance enabled her to continue her literary activities, filling a void in French literature created by the revolutionary chaos. It also provided her with a unique perspective from which to observe and analyze the Revolution, distinguishing her insights from those of her French contemporaries. For these reasons, she is regarded as a significant author of late 18th-century French literature, often mentioned alongside Germaine de Staël.

8.2. Social and Intellectual Impact

Isabelle de Charrière's ideas had a notable influence on various social and intellectual topics. Her advocacy for women's education and social reform resonated with progressive thinkers of her time. Her engagement with the French Revolution, through both her commentary and her critical observations of aristocratic refugees, remains a subject of particular interest for scholars studying the period.

Her legacy extends beyond her literary contributions. In 1991, the asteroid 9604 Bellevanzuylen was named in her honor. Her life and work were adapted into the 1993 film Belle van Zuylen - Madame de Charrière, directed by Digna Sinke. Furthermore, Utrecht University in the Netherlands established the Belle van Zuylen Chair in her name. The annual Belle van Zuylen Lecture, part of the International Literature Festival Utrecht (ILFU), addresses themes related to literature and society, delivered by contemporary authors such as Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Jeanette Winterson, Azar Nafisi, Paul Auster, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Margaret Atwood. Since 2020, recipients of this lecture have been awarded the Belle van Zuylenring, a small sculpture.

9. Discography

- Belle van Zuylen / Mme de Charrière: Een Muzikaal Verhaal ("A Musical Story"). Muziek van Belle van Zuylen, Frederik II van Pruisen, Anna Amalia van Pruisen, Jean Jacques Rousseau. Contents: Six minuets pour deux violons, alto et basse; Sonate voor Klavecimbel Opus 3 No. 1 in C-groot; Sonate voor Klavecimbel Opus 3 No. 2 Deel 1 in F-groot; et 8 Airs et Danses avec accompagnement de clavecin-Romance "Arbre Charmant"; "Pauvre Agneau"; "De la ville et des champs" (aria met twee violen en continuo); "Lise aimoit"; "Timarette s'en est allée" (aria met twee violen en continuo); autre air pour "Lise aimoit"; Air "Tout Cède A La Beauté"; Air "Douce Retraite." Utrechts Barok Consort m.m.v. Wilke te Brummelstreete. Utrecht: Slot Zuylen CD 423206, 2005.

- Belle van Zuylen (Madame de Charrière) and Contemporaries. Madelon Michel, soprano; Fania Chapiro, pianoforte. Contents: Sonata in C major Op. 2 No. 2; Airs et Romances: "L'an passé," "De la ville et des champs,", "Pauvre Agneau," "L'amour est un enfant trompeur," "Timarette s'en est allée," "Lise aimoit," autre air pour "Lise aimoit", "Arbre charmant," "Douce retraite," "Tout cède à la beauté d'Elise." (Contemporaries: Rameau, Sarti, Rousseau, and Cimarosa.) Rotterdam: Erasmus Muziek Producties, ©1994.