1. Overview

Hyman Philip Minsky (September 23, 1919 - October 24, 1996) was a prominent American economist and professor known for his research on financial crises and the inherent instability of capitalism. A distinguished scholar and a leading figure in post-Keynesian economics, Minsky emphasized the importance of government intervention in financial markets, opposing the widespread deregulation of the 1980s. He argued that the financial system is intrinsically fragile, prone to swings between stability and fragility that can lead to economic downturns. His most significant contribution is the Financial Instability Hypothesis, which explains how periods of economic prosperity can sow the seeds of future financial crises by encouraging excessive speculation and debt accumulation. His theories, particularly the concept of the "Minsky moment", gained renewed attention after the 2007-2008 global financial crisis as they provided a powerful framework for understanding the mechanisms of systemic financial collapse. Minsky also developed a theory outlining the evolution of capitalism through distinct stages, characterized by changes in financial systems and profit-seeking motives, further demonstrating his holistic view of economic development and instability.

2. Life

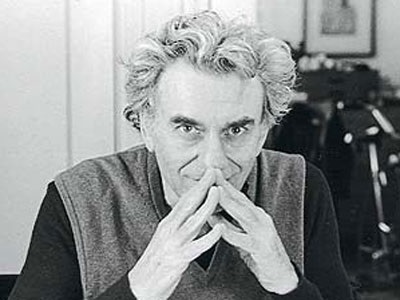

Hyman Philip Minsky's life was marked by his dedication to understanding the dynamics of capitalism and its inherent financial vulnerabilities, from his early life in a family with strong social convictions to his distinguished career as an academic.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Hyman Philip Minsky was born on September 23, 1919, in Chicago, Illinois, to a Jewish family of Menshevik emigrants from Belarus. His family background instilled in him an early awareness of social and economic issues; his mother, Dora Zakon, was actively involved in the nascent trade union movement, while his father, Sam Minsky, was a participant in the Jewish section of the Socialist Party USA in Chicago. He completed his secondary education at George Washington High School in New York City, graduating in 1937. Minsky pursued higher education at the University of Chicago, where he earned his Bachelor of Science (B.S.) degree in mathematics in 1941. He then continued his studies at Harvard University, obtaining both a Master of Public Administration (M.P.A.) and a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in economics. During his time at Harvard, Minsky had the opportunity to study under influential economists such as Joseph Schumpeter and Wassily Leontief, who significantly shaped his economic perspectives.

2.2. Career

Minsky embarked on a distinguished academic career, holding professorial positions at several prominent institutions. He began teaching at Brown University from 1949 to 1958. Following this, he served as an associate professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1957 to 1965. In 1965, he moved to Washington University in St. Louis, where he became a Professor of Economics, a position he held until his retirement in 1990. Toward the end of his life, Minsky was recognized as a Distinguished Scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, further solidifying his reputation as a leading economic thinker. In addition to his academic roles, Minsky also contributed to public policy as a consultant to the Commission on Money and Credit from 1957 to 1961, during his tenure at Berkeley.

3. Economic Theories and Contributions

Minsky's economic theories provided a critical lens through which to understand the inherent instability of financial markets and the dynamic evolution of capitalist systems. His work challenged mainstream economic thought by emphasizing the endogenous nature of financial crises.

3.1. Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH)

Minsky's seminal contribution is the Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH), which posits that financial fragility is an inherent feature of the normal life cycle of a capitalist economy. He argued that periods of prolonged economic prosperity and stability paradoxically lead to increased speculation and debt accumulation, ultimately making the financial system more vulnerable to crises. This process, Minsky believed, is endogenous to financial markets, meaning instability is built into the system rather than being caused by external shocks. He posited that as corporate cash flow increases beyond what is needed to pay off debt during prosperous times, a speculative euphoria develops. This leads to a situation where debts soon exceed what borrowers can realistically repay from their incoming revenues, which, in turn, triggers a financial crisis. Following such speculative borrowing bubbles, banks and lenders tighten credit availability, even for companies that are otherwise solvent, leading to a contraction of the economy. Minsky disagreed with many mainstream economists of his era who viewed market economies as inherently stable, arguing that without government intervention through financial regulation, central bank actions, and other tools, booms and busts are inevitable. These insights underscore the importance of robust regulatory frameworks to stabilize the financial system.

3.1.1. Core Concepts

A central concept of Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis is the "Minsky moment". This phrase refers to the critical point when the financial system rapidly shifts from stability to fragility, culminating in a crisis. It describes the sudden collapse of asset values after a prolonged period of growth and speculation, which triggers a wider financial crisis. Henry Kaufman, a prominent Wall Street money manager and economist, acknowledged Minsky's profound insights, stating that Minsky "showed us that financial markets could move frequently to excess" and "underscored the importance of the Federal Reserve as a lender of last resort". Minsky believed that these swings between robustness and fragility are an integral part of the process that generates business cycles.

3.1.2. Three Types of Finance

To illustrate the progression towards financial instability, Minsky identified three distinct types of borrowing or financial behavior that contribute to the accumulation of potentially insolvent debt in the non-government sector:

- Hedge finance: In this type, borrowers can make debt payments, covering both interest and principal, from their current cash flows generated by investments. This is the most stable form of finance, typically observed right after a financial crisis and during the initial recovery phase when both banks and borrowers are cautious. Loans are minimal and structured to ensure full repayment, making the economy self-containing and relatively stable.

- Speculative finance: Here, the cash flow from investments is sufficient to service the debt-that is, to cover the interest due-but the borrower must regularly roll over, or re-borrow, the principal. This type of finance emerges as confidence in the banking system is slowly renewed, leading to complacency that good market conditions will persist. Lenders issue loans where only interest payments are covered by current cash flows, with the principal expected to be repaid through future refinancing. This marks a decline towards instability.

- Ponzi finance: Named after Charles Ponzi, this is the most precarious form of finance. Ponzi borrowers take on debt based on the belief that the appreciation in the value of their assets will be sufficient to refinance the debt, as their current cash flows cannot even cover interest or principal payments. Only the continuously appreciating asset value can sustain a Ponzi borrower. This stage begins as confidence in the banking system continues to grow, and banks believe asset prices will keep rising, leading to loans where borrowers can afford neither the principal nor the interest from their current income.

The shift from hedge to speculative, and then to Ponzi finance, represents a gradual increase in financial fragility. If Ponzi finance becomes widespread within the financial system, the inevitable disillusionment when asset prices stop increasing can cause the system to seize up. When the bubble pops, speculative borrowers can no longer refinance their principal, even if they could cover interest payments. This can trigger a chain reaction, causing even hedge borrowers, who initially appeared sound, to collapse as they struggle to find new loans amidst tightening credit conditions, akin to a line of falling dominoes.

3.1.3. Application to the Subprime Mortgage Crisis

Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis gained significant relevance and was widely used to explain the 2007-2008 subprime mortgage crisis, with some observers labeling the event as a "Minsky Moment." Economist Paul McCulley applied Minsky's three types of finance to the mortgage market:

- A traditional mortgage loan, where both principal and interest are paid, represents hedge finance.

- An interest-only loan, where only interest is paid and the principal must be refinanced later, is an example of speculative finance.

- A negative amortization loan, where payments do not even cover the interest, and the principal balance actually increases, exemplifies Ponzi finance.

McCulley noted that the progression through Minsky's three borrowing stages was evident as the credit and housing bubbles built up through approximately August 2007. The rapidly expanding shadow banking system fueled this demand for housing, facilitating the shift towards more speculative and Ponzi-type lending through increasingly risky mortgage loans and higher levels of financial leverage. This amplified the housing bubble, as easily available credit encouraged higher home prices. After the bubble burst, the reverse progression was observed, with businesses deleveraging, lending standards tightening, and the proportion of borrowers shifting back towards the more stable hedge finance category.

Minsky also observed that human nature is inherently pro-cyclical, meaning that economic agents tend to amplify existing trends. As Minsky put it, "from time to time, capitalist economies exhibit inflations and debt deflations which seem to have the potential to spin out of control. In such processes, the economic system's reactions to a movement of the economy amplify the movement - inflation feeds upon inflation and debt-deflation feeds upon debt-deflation." This implies that people tend to act as momentum investors rather than value investors, thereby exacerbating the high and low points of economic cycles. A key implication for policymakers and regulators is the necessity of implementing counter-cyclical policies, such as increasing capital requirements for banks during boom periods and reducing them during busts, to mitigate these destabilizing pro-cyclical behaviors.

3.2. Theory of Stages of Capitalism

Minsky believed that the evolution of finance could explain the shifting nature of capitalism over time, influenced by his study under Joseph Schumpeter and his engagement with Keynesian economics. He argued that finance serves as the engine of investment in capitalist economies, and thus the changes in financial systems, driven by profit-seeking, lead to different stages of capitalism. Minsky identified four primary stages, each characterized by "what is being financed" and "who is doing the financing."

| Commercial | Financial | Managerial | Money-Manager | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Activity | Trade | Production | Aggregate Demand | Asset-Value |

| Object Financed | Merchants | Corporation | Managerial Corporation | International Corporation; Securities; Positions |

| Source of Financing | Commercial Bank (+ internal financing) | Investment Bank | Central Bank (+ internal financing) | Money-Fund |

3.2.1. Commercial Capitalism

Minsky's first period, Commercial Capitalism, corresponds to the era of merchant capitalism. During this stage, commercial banks leveraged their superior knowledge of distant banks and local merchants to generate profits. They issued bills for commodities, effectively creating credit for merchants and a corresponding liability for themselves. If unexpected losses occurred, they guaranteed payment. When a credit contract was fulfilled, the credit was extinguished. Banks primarily financed the inventories of merchants rather than capital stock. This meant that the main source of profit was through trade, not through expanding production as in later periods. Minsky explained that "commercial capitalism might well be taken to correspond to the structure of finance when production is by labor and tools, rather than by machinery and labor."

3.2.2. Financial Capitalism

The advent of the Industrial Revolution placed greater emphasis on the use of machinery in production, introducing significant non-labor costs. This necessitated the creation of "durable assets" and led to the emergence of the corporation as a distinct legal entity with limited liability for investors. The primary source of financing shifted from commercial banks to investment banks, particularly with the widespread growth of stocks and bonds in securities markets. As intense competition between firms could lead to price declines, threatening their ability to meet financial commitments, investment banks began to promote the consolidation of capital through facilitating trusts, mergers and acquisitions. This era of financial dominance was ultimately ended by the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Some economists, such as Charles Whalen and Jan Toporowski, propose an intermediary stage between commercial and financial capitalism. Whalen termed this "industrial capitalism" and Toporowski called it "classic capitalism," characterized by the traditional capitalist-entrepreneur who fully owned their firm and focused intensely on expanding production through developing capital assets, in contrast to the consolidation seen under Financial Capitalism.

3.2.3. Managerial Capitalism

Following the Great Depression, the nature of capitalism shifted once more. Drawing on the profit theory of Michał Kalecki, Minsky argued that the level of investment directly determines aggregate demand and, consequently, the flow of profits. He posited that "investment finances itself." According to Minsky, the Keynesian deficit spending policies adopted by post-depression economies, notably the New Deal in the United States, guaranteed a steady flow of profits. This enabled firms to finance their operations increasingly from retained profits, a practice not widely seen since the earliest period of capitalism. Management within firms gained greater independence from investment bankers and shareholders, which led to longer time horizons in business decisions, a development Minsky viewed as potentially beneficial. However, he also noted that firms became more bureaucratized, losing the dynamic efficiency characteristic of earlier capitalist stages, becoming "prisoners of tradition." Furthermore, government spending decisions shifted towards underwriting consumption rather than directly developing capital assets, which, while ensuring stable aggregate demand and preventing depressions or recessions, also contributed to a degree of economic stagnation.

3.2.4. Money Manager Capitalism

Minsky argued that changes in tax laws and the way markets capitalized on income led to a situation where the value of equity in indebted firms became higher than in conservatively financed ones. This triggered a significant shift in corporate control and financing. A market for the control of firms emerged, driven by fund managers whose compensation was directly tied to the total returns earned by the portfolios they managed. These managers were quick to accept higher prices for assets in their portfolios resulting from the refinancing that accompanied changes in firm control. Moreover, these money managers were also buyers of the liabilities (bonds) that arose from such refinancing.

The independence of operating corporations from money and financial markets that characterized managerial capitalism proved to be a transitory stage. The rise of these return- and capital-gains-oriented blocks of managed money meant that financial markets once again exerted a major influence on the economy's performance. However, unlike the earlier epoch of financial capitalism, the emphasis shifted away from the capital development of the economy. Instead, the focus became the quick returns of the speculator and trading profits. Minsky noted that the rise of money management, involving daily trading of multi-million dollar blocks, led to a surge in securities and individuals taking financial positions purely for profit. This positioning itself was financed by banks. At this point, Minsky observed that financial institutions had become far removed from directly financing capital development, instead committing large cash flows primarily to "debt validation." Jan Toporowski links this Money Manager Capitalism to contemporary trends in globalization and financialization.

3.3. Views on John Maynard Keynes

In his 1975 book, John Maynard Keynes, Minsky offered a critical assessment of the neoclassical synthesis's interpretation of Keynes's seminal work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Minsky argued that the neoclassical synthesis had de-emphasized or outright ignored crucial aspects of Keynes's original thought. He put forth his own interpretation, which notably emphasized concepts like Knightian uncertainty-the idea that certain future outcomes are unknowable and unquantifiable-which he believed were central to Keynes's understanding of economic dynamics and financial instability. Minsky's reading of Keynes highlighted the inherent fragility of capitalist economies and the necessity of robust institutional frameworks to manage financial instability, a perspective often overlooked in more conventional interpretations.

4. Selected Publications

Hyman Philip Minsky authored several influential books and numerous academic articles throughout his career, shaping the discourse on financial crises and the nature of capitalism. His key publications include:

- Ending Poverty: Jobs, Not Welfare. Levy Economic Institute, New York. (2013)

- John Maynard Keynes. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York. (1st Pub. 1975, 2008)

- Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York. (1st Pub. 1986, 2008)

- Can "It" Happen Again?. M.E. Sharpe, Armonk. (1982)

- "The breakdown of the 1960s policy synthesis". New York: Telos Press. (Winter 1981-82)

5. Assessment and Legacy

Minsky's work, initially considered outside the economic mainstream, has gained substantial recognition and influence, particularly in the aftermath of major financial crises, highlighting his foresight regarding systemic risk and the need for robust financial regulation.

5.1. Early Academic Reception

For several decades, Minsky's economic theories received limited attention within mainstream economics and had little direct influence on central bank policy. One reason for this was Minsky's preferred methodology: he often articulated his theories verbally and did not build complex mathematical models based on them. Instead, Minsky favored using interlocking balance sheets to model economies, a stark contrast to the prevalent mainstream economic models that largely omit private debt as a significant factor and are built upon utility and production functions. This methodological divergence meant his insights, which emphasized the macroeconomic dangers of speculative bubbles in asset prices, were not easily incorporated into the dominant theoretical frameworks of the time.

5.2. Reevaluation and Influence After Financial Crises

Despite early neglect, Minsky's theories experienced a dramatic reevaluation and surge in influence following the financial crisis of 2007-2010. The phrase "Minsky moment" became a widely used term in the media and financial circles to describe the sudden collapse of asset values and the subsequent financial turmoil that characterized the crisis. This renewed interest stemmed from the fact that Minsky's framework provided a compelling explanation for the crisis's origins and mechanisms, which many mainstream models had failed to predict or adequately account for.

In the wake of the crisis, there has been increased interest in the policy implications of Minsky's theories. Some central bankers and policymakers have advocated for the inclusion of a "Minsky factor" in central bank policy, indicating a recognition of the need for policies that address the inherent pro-cyclicality and potential for instability within financial markets. For instance, Janet Yellen, former Chair of the Federal Reserve, has discussed the lessons for central bankers from Minsky's work, particularly regarding financial stability and systemic risk. Minsky's legacy now underscores the importance of counter-cyclical regulatory measures, the role of central banks as lenders of last resort, and the necessity of robust financial supervision to prevent the build-up of excessive debt and speculative positions that can threaten overall economic stability. His work continues to inform discussions on macroprudential policy and the inherent fragility of modern financial systems.