1. Overview

Honinbo Shusaku, born Kuwabara Torajiro, was a preeminent Japanese professional Go player of the 19th century, widely regarded as one of the greatest players in the game's history. He is particularly renowned for his remarkable 19-game undefeated streak in the annual Edo Castle games, earning him the moniker "Invincible Shusaku." His name is also synonymous with the Shusaku fuseki, a strategic opening pattern he perfected that profoundly influenced Go for decades. Alongside his teacher, Hon'inbo Shūwa, and other historical masters like Honinbo Dosaku, Shusaku is considered to have been the strongest player of his era from around 1847 until his untimely death in 1862. His legacy extends beyond his playing achievements, encompassing his profound influence on modern Go strategy, his posthumous veneration as a "Go sage," and his enduring cultural impact, notably through popular media.

2. Early Life and Background

Honinbo Shusaku was born Kuwabara Torajiro on June 6, 1829, in Innoshima, a small island near the town of Onomichi in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. He was the second son of Kuwabara Wazo and his wife, Kame, who were merchants. From a very young age, Shusaku displayed an extraordinary talent for Go. His prodigious skill quickly caught the attention of Asano Tadahiro, the lord of Mihara Castle and the chief retainer of the Hiroshima Domain. After playing a game with the young Shusaku, Lord Asano became his patron, recognizing his exceptional potential. This patronage allowed Shusaku to pursue formal Go training under Lord Asano's personal instructor, the priest Hoshin, who himself was a professional-level player. By the age of eight in 1837, Shusaku had already achieved a level of play nearing professional caliber, setting the stage for his future career.

3. Entry into Honinbo and Early Career

In 1837, at the age of eight, Shusaku left his home in Innoshima to join the prestigious Honinbo school in Edo (modern-day Tokyo). The Honinbo school was the most significant institution in the world of Go in Japan at the time, having produced legendary figures like the "Go Saint" Honinbo Dosaku and numerous Meijin. Although he officially entered as a student of Honinbo Jowa, the 12th head of the Honinbo house, Shusaku primarily studied under the guidance of senior students within the school. His talent was immediately recognized; Jowa himself reportedly praised Shusaku's playing style, declaring him a "Go master of the last 150 years," a period that encompassed Dosaku's prime.

Shusaku's progress was rapid. On January 3, 1840, he received his shodan (first dan) professional diploma, marking his official entry into the professional Go world. The following year, in 1840, he changed his name to Shusaku and was promoted to 2-dan. He continued his steady ascent through the ranks, achieving 3-dan in 1841 and 4-dan in 1842. In 1844, after reaching 4-dan, he returned home for an extended period.

His early career was also marked by a significant encounter in April-May 1846, when he returned to Edo and played against Gennan Inseki, who was arguably the strongest player of that era. Initially, Shusaku played with a handicap of two stones. However, Gennan quickly recognized Shusaku's immense strength and called off the game, acknowledging that the handicap was insufficient. A new game was then initiated with Shusaku playing black without a handicap, a match that would become famously known as the "ear-reddening game." Gennan later remarked that Shusaku's skill during that period was no less than 7-dan.

In 1848, Shusaku was formally designated as the 14th Honinbo heir, concurrently being promoted to 6-dan. He also married Hana, the daughter of Honinbo Jowa. His position as the official heir to the head of the Honinbo house placed him in an eminent position within the Go world. He continued to advance, eventually reaching 7-dan, though the exact year is debated, with some sources indicating 1849 and others 1853. After forcing his primary rival and friend, Ota Yuzo, to accept a handicap, Shusaku was widely acknowledged as the strongest player of his time, second only to his teacher, Honinbo Shuwa.

4. Professional Career and Achievements

Shusaku's professional career was distinguished by his consistent excellence and groundbreaking contributions to Go strategy. He was known for his calm and precise playing style, combined with an accurate judgment of the board.

4.1. Castle Games and Undefeated Streak

Shusaku's participation in the annual Edo Castle games (御城碁OshirogoJapanese), played in the shogun's castle, was a highlight of his career. Beginning in 1849, he embarked on an unprecedented 19-game winning streak in these prestigious matches, a perfect record of 19 wins and no losses. This remarkable performance earned him the enduring nickname "Invincible Shusaku." This undefeated run is often cited as a primary reason for arguments that Shusaku was the strongest player in Go history. However, it is noted that Shusaku was very particular about maintaining this streak, reportedly declining to play certain handicap games where a guaranteed win was not assured, such as a two-stone handicap game against Hayashi Yumi (then 5-dan) or a similar offer against Yasui San-ei (then 2-dan). Conversely, it is also said that he was willing to play white without komi against any opponent.

The following table details Shusaku's 19 consecutive victories in the Castle Games:

| No. | Year | Opponent | House | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1849 | Yasui Sanchi | Yasui | Black by 11 points |

| 2 | Sakaguchi Sentoku | Sakaguchi | Black by resignation | |

| 3 | 1850 | Sakaguchi Sentoku | Sakaguchi | Black by 8 points |

| 4 | Ito Showa | Black by 3 points | ||

| 5 | 1851 | Hayashi Monnyu | Hayashi | Black by 7 points |

| 6 | Yasui Sanchi | Yasui | Black by resignation | |

| 7 | 1852 | 12th Inoue Inseki | Inoue | White by 2 points |

| 8 | Ito Showa | Black by 6 points | ||

| 9 | 1853 | Sakaguchi Sentoku | Sakaguchi | Black by resignation |

| 10 | Yasui Sanchi | Yasui | White by 1 point | |

| 11 | 1854 | 12th Inoue Inseki | Inoue | White by resignation |

| 12 | 1856 | Ito Showa | White by resignation | |

| 13 | 1857 | Yasui Sanchi | Yasui | Black by resignation |

| 14 | 1858 | Sakaguchi Sentoku | Sakaguchi | White by 3 points |

| 15 | 1859 | Ito Showa | Black by 9 points | |

| 16 | Hattori Seitetsu | Hattori | Black by 13 points | |

| 17 | 1860 | Hayashi Yumi | Hayashi | White by 4 points |

| 18 | 1861 | Hayashi Monnyu | Hayashi | White by 14 points |

| 19 | Hayashi Yumi | Hayashi | White by resignation |

4.2. Major Games and Rivalries

Beyond the Castle Games, Shusaku engaged in several other significant matches that showcased his prowess. His encounter with Gennan Inseki in 1846, known as the "ear-reddening game," is one of the most famous in Go history. In this game, Shusaku, playing black, made a mistake in response to a new joseki (corner opening variation) introduced by Gennan. Despite being in a disadvantageous position, Shusaku fought back fiercely. During the middlegame, most spectators believed Gennan was winning, except for a doctor who was observing. The doctor, though not skilled in Go, noticed Gennan's ears turned red after a particular move by Shusaku, indicating surprise and perhaps a loss of confidence. This move, Black's 127th, became known as the "ear-reddening move" (耳赤の一局mimi-aka no ikkyokuJapanese). Shusaku ultimately won the game by two points. The move is considered a brilliant stroke that simultaneously expands the top side's territory, reduces White's influence on the right, indirectly aids a weak stone on the bottom, and targets an invasion on the left side.

Another significant rivalry was his thirty-game match (三十番碁SanjubangoJapanese) against Ota Yuzo. This unprecedented series of games began in 1853, sponsored by the famous Go patron Akai Gorosaku. At the time, Ota was 46 years old and a 7-dan, while Shusaku was 24 and a 6-dan. The games were played weekly, a faster pace than typical ten-game matches (jubango). Ota initially performed well, but Shusaku mounted a strong comeback after the 11th game, leading by four games after the 17th. The 21st game was played in July, but the 22nd was delayed until October for unknown reasons and was played at Ota's house, a departure from the usual neutral venues. After Ota lost again, the venue was moved back to a neutral location. It is widely believed that the 23rd game, which lasted nearly 24 continuous hours and resulted in a tie, was fixed to save Ota from embarrassment. This tie, achieved by Ota playing white, was considered a great achievement and, along with Shusaku's call-up for the Castle Games, served as a pretext to adjourn the match.

4.3. Playing Style and Key Moves

Shusaku's playing style was characterized by its simplicity, elegance, and profound depth. He was known for his solid and unyielding approach, particularly when playing with black. His games demonstrated an accurate sense of judgment and an ability to maintain a calm demeanor even in complex situations.

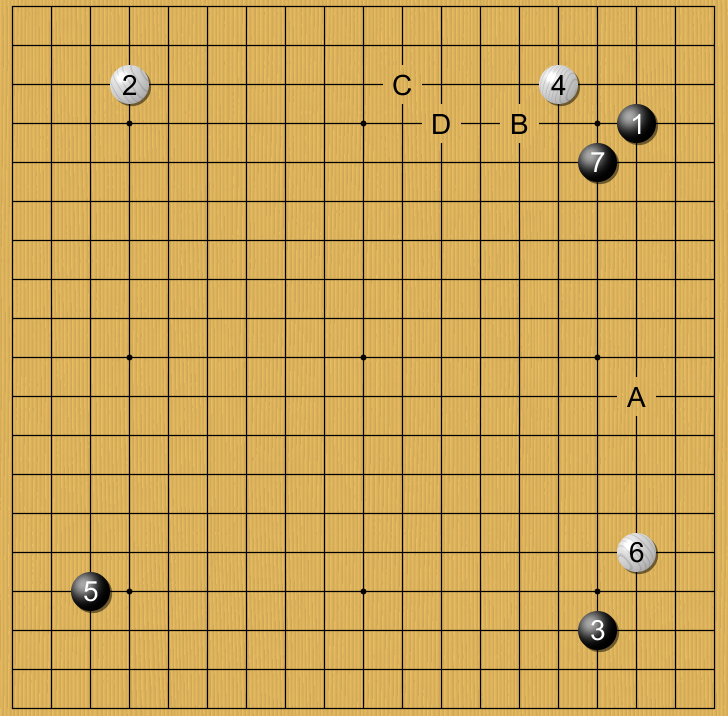

The most famous aspect of his style is the Shusaku fuseki (秀策流Shūsaku-ryūJapanese), a specific opening pattern for black. While he did not invent the individual moves, he developed this opening to perfection, making it the dominant opening style until the 1930s. The Shusaku fuseki typically involves black playing on three different komoku (3-4 point) corners, often followed by a kosumi (diagonal move) at the 7th move. This particular kosumi, known as "Shusaku's kosumi," was highly effective in building a solid position. Shusaku himself is famously quoted as saying, "As long as the size of the Go board does not change, this kosumi will never be considered a bad move." His black games were described as "absolutely solid." An anecdote recounts that when asked about the result of a Castle Game, Shusaku would simply reply, "I played black," implying that the outcome was a foregone conclusion.

Modern re-evaluations, particularly by Go artificial intelligence programs, have offered new perspectives on Shusaku's play. Before the rise of Go AI, the Shusaku fuseki was sometimes considered "slow" or "mild" for modern Go, especially in games with komi (points awarded to White to compensate for Black's first move advantage). However, in 2019, FineArt (絕藝JuéyìChinese), a top Go AI that won the 2019 World Computer Go Open, identified Shusaku's kosumi as a best move in certain contexts, leading to a re-evaluation of Shusaku's foresight. While Go AIs like KataGo may not always rate the "ear-reddening move" as the immediate best move, they often identify the area as a strong candidate a few moves later, suggesting Shusaku's move might have been slightly early but still strategically sound, potentially serving as a psychological move to disrupt the opponent's rhythm. The Shusaku fuseki has since seen a resurgence in professional title matches, reaffirming its status as a powerful opening strategy.

5. Personal Life

Honinbo Shusaku's personal life was deeply intertwined with his professional obligations and his strong sense of loyalty. In 1848, the same year he was officially named the 14th Honinbo heir, he married Hana, the daughter of Honinbo Jowa, the 12th head of the Honinbo house.

Despite his eminent position as the Honinbo heir, Shusaku initially declined the offer, citing his obligations and loyalty to his patron, Lord Asano Tadahiro, the lord of Mihara Castle. As a retainer of Lord Asano, becoming the head of a Go house would also mean becoming a retainer of the Shogun, a conflict of loyalty that Shusaku was reluctant to accept. His steadfast refusal to accept the Honinbo heirship, an unprecedented act, highlights his strong sense of duty to his original lord. The issue was eventually resolved, allowing him to accept the heirship.

His respect for his teacher, Honinbo Shuwa, was also a defining characteristic of his personal and professional life. Shusaku consistently refused to play with white against Shuwa, even when his winning record against his teacher suggested a change in handicap was due. When Shuwa suggested adjusting their handicap to `sen-ai-sen` (where the stronger player takes black two out of three games), Shusaku reportedly replied, "I cannot take black against my teacher." This unwavering deference meant there was no clear measure of the precise difference in strength between them, though many believed Shuwa was stronger. For instance, while Shusaku found Ota Yuzo a tough opponent despite having a winning record against him, Shuwa reportedly defeated Ota with ease.

6. Death

In 1862, a severe cholera epidemic swept across Japan, causing widespread devastation. The Honinbo house, where Shusaku resided, was also affected, with several patients falling ill. Despite warnings from his teacher, Honinbo Shuwa, Shusaku selflessly dedicated himself to tending to the sick within the Honinbo household. His compassionate actions, however, led to his own infection. Honinbo Shusaku succumbed to cholera on September 3, 1862, at the young age of 33 (or 34 by traditional Japanese reckoning). His death occurred in the same year that the annual Castle Games were canceled, marking the end of an era. It is notable that, thanks to Shusaku's care, he was the only casualty of the cholera outbreak within the Honinbo house. His death is often seen as a testament to his noble character, extending beyond his exceptional skill in Go.

7. Legacy and Influence

Honinbo Shusaku's impact on the world of Go and Japanese culture has been profound and enduring, solidifying his status as one of the game's immortal figures.

7.1. Influence on the Go World

Shusaku's most direct and lasting contribution to Go strategy is the Shusaku fuseki. Although he did not invent all its components, he refined and popularized this opening pattern, particularly for black, to such an extent that it dominated professional play for nearly a century until the 1930s. His deep understanding of the opening's nuances and its inherent solidity made it a cornerstone of Go theory. Even today, with the advent of Go AI, the Shusaku fuseki and its core principles continue to be studied and, in some cases, re-validated, demonstrating his strategic foresight.

His influence extends to the concept of the "Shusaku number," an equivalent of the Erdős number for Go players, which measures the "collaborative distance" between a Go player and Shusaku based on their shared games. This concept highlights his central position in the history of Go.

Many professional Go players, including modern masters, have studied Shusaku's games extensively. For example, Lee Chang-ho, a prominent Korean Go player, is known to have diligently reviewed Shusaku's game records from a young age, reportedly stating, "I will never be able to reach the level of Master Shusaku, even if I spend my entire life." Approximately 400 of Shusaku's game records have been preserved, compiled in works such as "Kōgyoku Yoin" (敲玉余韵Japanese) in 1900, serving as invaluable educational material for aspiring and professional players alike.

7.2. Cultural Impact

Shusaku's legacy transcends the professional Go world, permeating popular culture. He is prominently featured in the acclaimed manga and anime series Hikaru no Go. In the fictional narrative, Shusaku is depicted as a previous host for the spirit of Fujiwara-no-Sai, a genius Go player from the Heian period. This portrayal introduced Shusaku to a new generation of fans, particularly children, who came to recognize him as one of the "strongest figures in Go history" during the "Go boom" sparked by the series.

His life and achievements are commemorated in various physical landmarks. The Itsusaki Shrine in Mihara City, Hiroshima Prefecture, still houses a stone monument erected in the Edo period in honor of Shusaku, which also appears in Hikaru no Go. His birthplace in Innoshima has been preserved and transformed into the "Honinbo Shusaku Go Memorial Museum," attracting visitors interested in his life and the game of Go. Recognizing this historical connection, Onomichi City, which includes Innoshima, has designated Go as its "city skill" and hosts the Honinbo Shusaku Go Festival twice a year.

In 2004, Honinbo Shusaku was among the first four individuals to be inducted into the Go Hall of Fame, alongside figures like Tokugawa Ieyasu, Honinbo Sansa, and Honinbo Dosaku, further cementing his place in Go history.

7.3. Historical Evaluation and Re-evaluation

Historically, the title of "Go sage" (棋聖KiseiJapanese) in the Edo period was typically reserved for two masters: Honinbo Dosaku and Honinbo Jowa. However, in the Meiji era and beyond, Shusaku's popularity surged, leading to his recognition as a "Go sage" alongside Dosaku, effectively replacing Jowa in this esteemed trio. Despite never achieving the rank of Meijin, many consider him a strong candidate for the title of "strongest player in history."

While his reputation remains high in Japan, where numerous texts on both Shusaku and Jowa have been published, his standing in the West has sometimes been described as "inflated" due to scarcer historical sources. However, modern re-evaluations, particularly those aided by Go AI, have provided new insights. While some of his moves, like the "ear-reddening move," might not be deemed the absolute "best" by AI, their strategic depth and psychological impact are still highly regarded. Some analyses suggest that AI's lower evaluation of certain moves might be due to their psychological or rhythm-breaking nature, which AI might not immediately recognize as optimal but eventually converges upon.

Shusaku's posthumous recognition also faced a minor controversy on June 6, 2014, when a Google Doodle commemorated his 185th birthday. This caused a stir in the United Kingdom, as some felt it was impolitic to honor a Japanese figure on the 70th anniversary of the Normandy landings (D-Day). Google.uk subsequently made hurried amendments to its homepage. This incident highlights the complexities of historical memory and public perception in a global context.

8. Related Works

Honinbo Shusaku's life and games have inspired various works across different media:

- Invincible: The Games of Shusaku by John Power

- Honinbo Shusaku - Complete Game Collection

- Kōgyoku Yoin (敲玉余韵Japanese) - a collection of his game records compiled by Ishitani Kōsaku in 1900.

- Shusaku (秀策Japanese) - part of the "Nihon Igo Taikei" series, with commentary by Ishida Yoshio and text by Tamura Takao.

- Dōsaku, Shūsaku, Go Seigen: Michi o hiraita sandai kyosei (道策・秀策・呉清源-道を拓いた三大巨星Japanese) by Ishida Yoshio.

- Shūrei Shūsaku (Igo Koten Meikyoku Senshū) (秀麗秀策 (囲碁古典名局選集)Japanese) by Fukui Masaaki.

- Meijin Meikyokushū Shūsaku (名人・名局選 秀策Japanese) by Fukui Masaaki.

- Shūsaku Kiwami no Itte (秀策極みの一手Japanese) by Takagi Shoichi.

- Kanbon Honinbo Shusaku Zenshu (完本 本因坊秀策全集Japanese).

- Hikaru no Go - a popular manga and anime series featuring Shusaku as a key historical figure.

- Honinbo Shusaku Igo Trainer - a computer game for the PC-8800 series released in 1983.

- Shusaku Oshirogo Collection - a computer game for the FM-8.