1. Overview

Homer Bezaleel Hulbert (January 26, 1863 - August 5, 1949) was an American missionary, journalist, linguist, and fervent Korean independence activist. He played a multifaceted role in Korea, serving as an educator, a scholar of the Korean language, and a key advisor to Emperor Gojong during the late Korean Empire. Hulbert is widely recognized for his deep appreciation and promotion of Hangul, the Korean alphabet, and his unwavering commitment to Korean sovereignty against Japanese imperial ambitions. His contributions extended to various fields, including education, media, and social development, making him one of the most beloved foreigners in Korean history, esteemed for his dedication to social progress and national self-determination. In Korea, he was known by various names, including 허할보Hŏ HalboKorean, 허흘법Hŏ HŭlpŏpKorean, and 할보HalboKorean.

2. Early Life and Education

Hulbert's formative years in the United States laid the groundwork for his future dedication to Korea, shaped by his family's intellectual and religious heritage and his academic pursuits.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Homer Bezaleel Hulbert was born on January 26, 1863, in New Haven, Vermont, United States. He was the second of six children born to Calvin Butler Hulbert and Mary Elizabeth Woodward Hulbert. His father, Calvin Hulbert, was a prominent theologian and served as the president of Middlebury College in Vermont. His mother, Mary Woodward Hulbert, was the great-granddaughter of Eleazar Wheelock, the founder of Dartmouth College. Mary was born in Sri Lanka, as her father was a missionary who worked there and in India. Hulbert was raised under the family motto, "Character is more fundamental than victory," a principle that profoundly influenced his life and work.

2.2. Education

Hulbert's educational journey began with his graduation from St. Johnsbury Academy. He then pursued higher education at Dartmouth College, graduating in 1884. Following his studies at Dartmouth, he enrolled in Union Theological Seminary in New York, continuing his preparation for a life of service. In 1884, John Eaton, the U.S. Commissioner of Education, proposed to Hulbert's father the idea of sending one of his sons as a teacher to Korea, which had recently signed the Joseon-U.S. Treaty of Amity and Commerce. Homer Hulbert volunteered for this mission. However, his departure was delayed due to the Gapsin Coup in December 1884. Undeterred, Hulbert continued his studies on Korea and East Asia, eventually suspending his studies at Union Theological Seminary in 1886 to embark on his journey to Joseon.

3. Missionary and Educational Activities in Korea

Hulbert's arrival in Korea marked the beginning of significant contributions to the nation's educational and cultural landscape, where he became a pivotal figure in modernizing its institutions and promoting its unique heritage.

3.1. Teaching at Yukyeong Gongwon

Homer Hulbert arrived in Jemulpo (present-day Incheon) on July 5, 1886, accompanied by two other instructors, Delzell A. Bunker and George W. Gilmore. They immediately proceeded to Seoul, where they became teachers at Yukyeong Gongwon (Royal English School), the first national modern school in Joseon. Hulbert taught English and geography to the children of Korean royalty and nobility. From March 1888, he also taught students at the Jejungwon (first Western-style hospital in Korea) for two hours daily. Recognizing the importance of effective communication, Hulbert began studying Korean immediately upon his arrival, hiring a private tutor to accelerate his learning. Within four days, he was able to read and write Hangul, and within a week, he observed that Koreans often disregarded their own great writing system. His proficiency in Korean grew rapidly, enabling him to author books in Hangul within three years.

Hulbert's appreciation for Hangul deepened during an English examination at Yukyeong Gongwon, where he witnessed Emperor Gojong read English sentences transcribed into Hangul, despite not knowing English himself. This experience highlighted Hangul's phonetic superiority and its ability to accurately represent foreign sounds without requiring separate phonetic symbols, prompting Hulbert to begin his in-depth research into the Korean alphabet.

3.2. Paejae Hakdang and Contributions to Education

After a brief return to the United States in 1891, where he served as principal of Putnam Military Academy in Ohio and continued his writings on Hangul, Hulbert returned to Korea on October 14, 1893, as a missionary for the American Methodist Episcopal Church. He took charge of the Samun Publishing House, the Methodist publishing arm in Korea. Having received training in publishing in the U.S., he brought a new printing press from Cincinnati. Within a year of his appointment, Samun Publishing House became self-sufficient, printing over a million pages of evangelical tracts and religious books.

Hulbert also taught at Paejae Hakdang, a prominent modern school, where he mentored influential figures such as Seo Jae-pil, Syngman Rhee, and Ju Si-gyeong. His influence on these future leaders was profound. In 1895, he resumed publication of The Korean Repository, an English monthly magazine that had been suspended for two years, and published the first Korean translation of an English novel, The Pilgrim's Progress (텬로력뎡). That same year, he devised a system for the Romanization of Hangul.

Following the Eulmi Incident (assassination of Empress Myeongseong) on October 8, 1895, Hulbert, along with Horace Grant Underwood and Oliver R. Avison, stood guard at Emperor Gojong's sleeping quarters. In April 1896, he collaborated with Seo Jae-pil and Ju Si-gyeong to launch Dongnip Sinmun (The Independent), Korea's first private newspaper, which was printed at Samun Publishing House under Hulbert's supervision. He continued his linguistic work with Ju Si-gyeong, advocating for the introduction of spacing, periods, and commas in Hangul and repeatedly proposing the establishment of a National Language Research Institute to Emperor Gojong.

In May 1897, Hulbert signed an employment contract with the Korean government, becoming the head of Hansung Normal School, which had 50 students, and also taught at the Royal English School. From 1900 to 1905, he served as a teacher at Gwanrip Junggyo (the predecessor to Gyeonggi High School), actively engaging in social activities that criticized Japanese injustices. His wife, May Hannah Hulbert, whom he married in 1888 and brought back to Korea, taught music at Ewha Hakdang and tutored foreign children at their home.

Hulbert also served as the pastor of Baldwin Church, now Dongdaemun Methodist Church. In this role, he translated foreign books and promoted Korea abroad through numerous writings. He developed a keen interest in Korean history, assisting in the publication of Yoon Gi-jin's Daedong Gi-nyeon (大東紀年), a Korean history book, in 1903. In 1908, he co-authored Daehan Yeoksa (대한역사), a pure Hangul history textbook, with his student Oh Seong-geun from Gwanrip Junggyo. Although planned for two volumes, only the first was published. This book was subsequently banned by Japanese authorities in 1909, with all copies at the publishing house confiscated and burned.

3.3. Media and Publishing Activities

Hulbert was a significant figure in the development of modern Korean media. He served as the editor of The Korean Repository, a monthly English magazine published from 1892 to 1898, which aimed to inform the international community about Korea. In 1901, he founded and edited The Korea Review, an English monthly magazine that continued until 1906. This publication served as a crucial platform for disseminating information about Korea, promoting Korean culture, and criticizing Japanese imperial policies. His involvement with Dongnip Sinmun as its printer further solidified his role in supporting independent journalism in Korea.

3.4. YMCA Activities

Hulbert played a foundational role in the establishment of the Korean YMCA. He served as its first president, actively working towards youth enlightenment and social development. His efforts contributed significantly to fostering a modern civic society in Korea.

4. Hangul Research and Promotion

Hulbert's profound appreciation for Hangul, the Korean alphabet, led him to dedicated research and advocacy, recognizing its pivotal role in preserving Korean culture and national identity.

4.1. Research on Hangul's Excellence

Hulbert was a staunch advocate for Hangul, proclaiming it to be "the most excellent writing system in existence." He actively encouraged its use over the more complex Chinese characters, which were favored by the ruling class. In 1892, he published a scholarly paper titled "The Korean Alphabet," in which he lauded King Sejong the Great's creation of Hangul as a brilliant achievement in human history. He further elaborated on Hangul's superiority in a paper presented in the 1903 annual report of the Smithsonian Institution, concluding that "Hangul is superior to the English alphabet as a medium of communication." He also published papers on other aspects of Korean culture, including Korean metal movable type and the turtle ship.

4.2. Textbook Compilation and Distribution

In 1889, Hulbert authored Samin p'ilchi (사민필지, Essential Knowledge for Scholars and Commoners), the first geography textbook written entirely in Hangul. This book, used as a textbook at Yukyeong Gongwon, provided comprehensive information on global geography, societies, and cultures. In its preface, Hulbert lamented the prevailing attitude among Korea's ruling class who clung to Chinese characters while disparaging Hangul, despite its excellence. He continued to produce educational materials, publishing a total of 15 Hangul textbooks by 1908.

4.3. Linguistic Contributions

Hulbert made specific and significant contributions to Korean linguistics. Collaborating with his student, the prominent Korean linguist Ju Si-gyeong, he worked on refining Hangul orthography, actively advocating for the introduction of spacing, punctuation marks (like periods and commas), which were not traditionally used in Korean writing. He also devised a system for the Romanization of Hangul in 1895. His linguistic interests extended to comparative studies, as evidenced by his 1905 paper, Comparative Grammar of Korean and Dravidian, which compared Korean with the Dravidian languages of India. This interest was partly influenced by his maternal grandfather, Henry Woodward, who was a missionary in India, and his mother, Mary Woodward, who was born there.

5. Support for Korean Independence

Hulbert's unwavering commitment to Korean sovereignty intensified as Japanese imperial ambitions grew, leading him to actively participate in the Korean independence movement and advocate for self-determination on the international stage.

5.1. Gojong's Trust and Diplomatic Activities

From the mid-1890s, as Joseon faced increasing threats from Imperial Japan, Hulbert became deeply concerned with Korea's domestic and international political affairs, dedicating himself to the restoration of its sovereignty. After the 1895 Eulmi Incident, Hulbert became a trusted confidant and advisor to Emperor Gojong, serving as a vital diplomatic conduit between the Korean Empire and Western nations, including the United States. He was one of the most trusted foreigners by Gojong, who appointed him as a special envoy on three separate occasions. From 1903, Hulbert served as a guest correspondent for The Times, and from 1904, for the Associated Press, providing in-depth coverage of the Russo-Japanese War.

5.2. Opposition to the Eulsa Treaty and Appeals to the International Community

Hulbert's initial positive view of Japanese involvement in Korea, seeing them as agents of reform, shifted dramatically in September 1905 when he became a vocal critic of Japan's plans to turn the Korean Empire into a protectorate. After the Eulsa Treaty (also known as the Eulsa Protectorate Treaty) was imposed, stripping Korea of its diplomatic rights, Hulbert actively sought to expose its illegality and invalidity to the international community. In 1905, Emperor Gojong appointed him as a special envoy to deliver a personal letter to U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, protesting the treaty's illegality.

Hulbert informed the U.S. Minister to Korea of his mission and departed immediately. However, upon arrival in Washington D.C., he was denied an audience with both President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Elihu Root. In a statement submitted to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Hulbert expressed his shock at the refusal, noting that the rejection of the Emperor's letter was clearly premeditated. He highlighted the existing Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Korea and the U.S., which stipulated mutual assistance in times of distress, and questioned why the U.S. legation in Seoul was being withdrawn. This refusal stemmed from the secret Taft-Katsura Agreement of July 1905, in which the U.S. had already conceded Japan's dominance over Korea. Despite the clear violation of the treaty, the U.S. government's actions accelerated Japan's annexation of the Korean Empire.

5.3. Support for the Hague Emissary Affair

In 1907, Hulbert played a crucial role in facilitating the secret dispatch of three Korean emissaries-Yi Jun, Yi Sang-seol, and Yi Wi-jong-to the Second Hague Peace Conference in the Netherlands, carrying Emperor Gojong's secret letter. He significantly contributed to the preparatory work, evading the surveillance of the Japanese Resident-General, earning him the moniker "the fourth emissary." However, due to Japanese interference, the emissaries were denied entry to the conference. This failure became a pretext for Japan to force Gojong's abdication and led to Hulbert's effective expulsion from the Korean Empire by Itō Hirobumi, the Japanese Resident-General, on May 8, 1907.

5.4. Support for the Independence Movement in the US

After being expelled from Korea, Hulbert returned to the United States, where he continued his fervent advocacy for Korean independence. He actively supported Korean independence activists in the U.S., including Seo Jae-pil and Syngman Rhee. He traveled across the U.S., vehemently condemning Japan's aggressive actions and appealing for Korea's right to self-determination. In 1918, he co-authored an "Independence Petition" with Yeo Un-hong for the Paris Peace Conference. He strongly supported the March 1st Movement of 1919, publishing articles in support of it in a magazine overseen by Seo Jae-pil and testifying before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee about Japanese atrocities. In 1942, he attended the Korean Liberty Conference held in Washington, D.C.. In a 1944 publication by the Korean Problem Research Society titled Voice of Korea, Hulbert asserted that President Roosevelt's refusal to accept Emperor Gojong's plea after the Eulsa Treaty had altered the course of East Asian history, and that America's pro-Japanese policy had ultimately led to the Pacific War.

6. Writings and Thought

Hulbert's intellectual contributions provided valuable insights into Korean society and modernization, articulated through his extensive writings and scholarly works.

6.1. Main Thoughts and Perspectives

Hulbert's perspectives on Korean culture, modernization, and colonialism evolved significantly. Initially, he viewed Japan as a potential agent of reform in Korea, contrasting it with what he saw as reactionary Russia. However, this view shifted dramatically as he witnessed Japan's aggressive imperialistic policies. His 1906 book, The Passing of Korea, became a scathing critique of Japanese rule. His opposition to colonialism was not merely theoretical; he was deeply concerned that modernization under secular Japanese influence was inferior to a Christian-inspired modernization, which he believed would genuinely benefit Korea. He believed in the inherent strength and potential of the Korean people and their culture, particularly Hangul, which he saw as a symbol of their unique identity and intellectual prowess.

6.2. Representative Works and Papers

Hulbert was a prolific writer, contributing numerous books and papers that shaped international understanding of Korea.

- 1889: Samin p'ilchi (사민필지, Essential Knowledge for Scholars and Commoners), the first pure Hangul geography textbook.

- 1892-1898: Editor of The Korean Repository, an English monthly magazine.

- 1892: "The Korean Alphabet," a paper praising Hangul.

- 1901-1906: Editor and publisher of The Korea Review, an English monthly magazine.

- 1903: Sign of the Jumna.

- 1903: Search for a Siberian Klondike.

- 1903: Assisted in the publication of Yoon Gi-jin's Daedong Gi-nyeon (大東紀年), a Korean history book.

- 1903: Published a paper on the superiority of Hangul in the Smithsonian Institution's annual report.

- 1905: The History of Korea, which became a standard source on Korean history in the U.S. for about half a century.

- 1905: Comparative Grammar of Korean and Dravidian.

- 1906: The Passing of Korea, a critical account of Japanese rule. This work is considered one of the three major foreign accounts of late Joseon, alongside William Elliot Griffis's Hermit Kingdom and Isabella Bird Bishop's Korea and Her Neighbors.

- 1907: The Japanese in Korea: Extracts from The Korea Review.

- 1908: Co-authored Daehan Yeoksa (대한역사), a pure Hangul history textbook, with Oh Seong-geun.

- 1925: Omjee - The Wizard.

- 1926: The Face in the Mist.

- 1928: The Mummy Bride.

7. Personal Life

Hulbert's personal life in Korea was marked by deep relationships, particularly his close friendship with Emperor Gojong, and his family's integration into Korean society.

7.1. Personal Relationships and Friendship with Gojong

Hulbert was widely known to be a close personal friend of Emperor Gojong. This friendship was so profound that Hulbert stood guard at Gojong's palace during the Eulmi Incident in 1895. His deep trust with the Emperor allowed him to serve as a crucial intermediary in diplomatic efforts. Hulbert married May Hannah in 1888, and she accompanied him back to Korea, where she taught music at Ewha Hakdang and tutored foreign children at their home. Their first son, Sheldon, died at the age of two and was buried in Yanghwajin.

Regarding his anthropological views, Homer Hulbert stated that Korea and Japan shared the same two racial types, but Japan was predominantly Malay, while Korea was mostly Manchu-Korean. He also suggested that although Korea was physically mostly of the northern type, this did not disprove his claim that the Malay element developed Korea's first civilization, even if it did not necessarily originate it, and that the Malay element imposed its language in its main features across the entire peninsula. Hulbert also believed that a genetic admixture with Chinese blood in Korea had ceased over a thousand years prior.

8. Later Life and Death

Hulbert's final years saw his return to the Korea he loved, where he ultimately passed away, leaving behind a legacy enshrined in his final resting place.

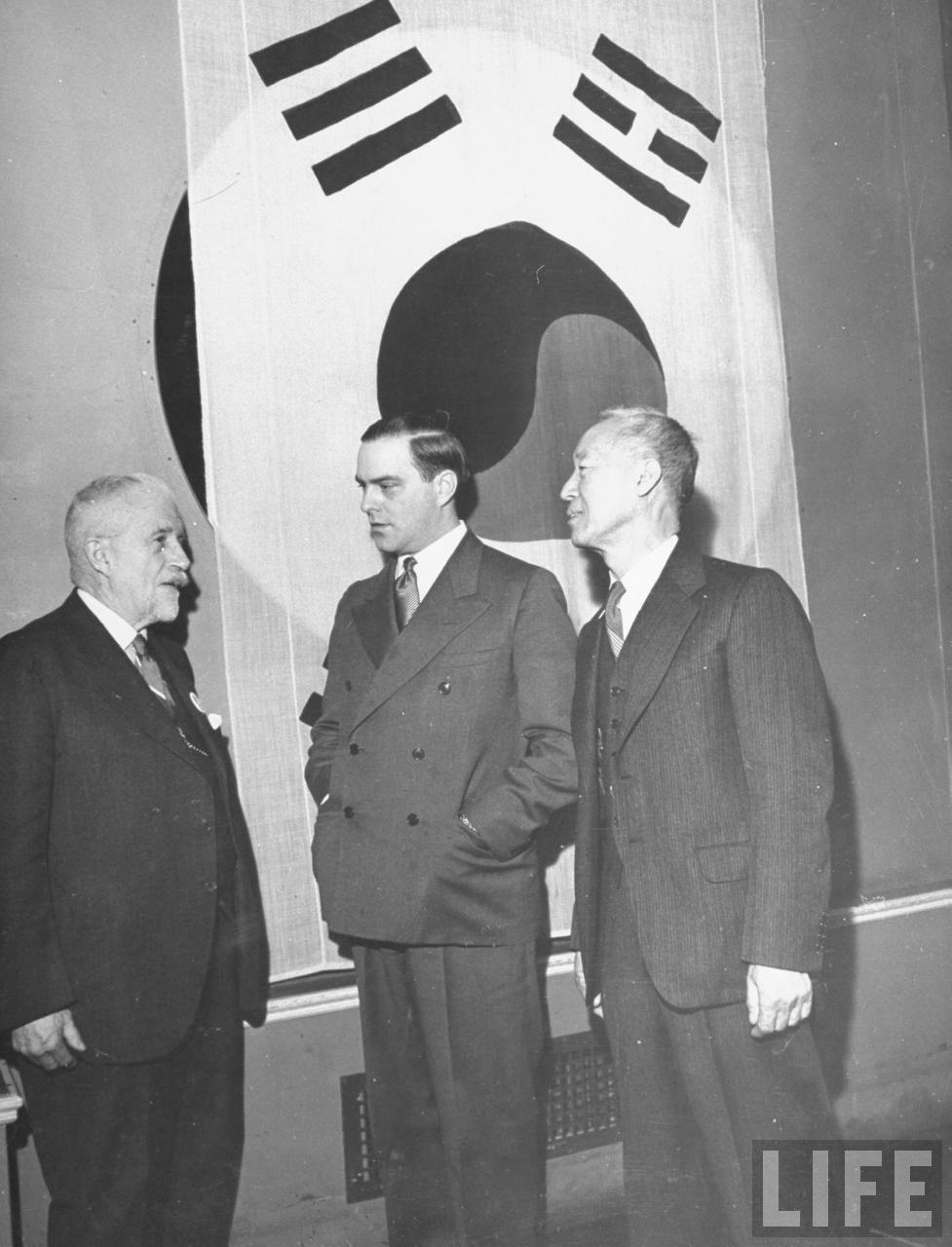

8.1. Return to Korea and Death

In 1948, Syngman Rhee, one of Hulbert's former students at Paejae Hakdang and now the first President of the newly established Republic of Korea, invited Hulbert to return to Korea. On July 29, 1949, at the age of 86, Hulbert embarked on the journey, returning to Korea after 40 years, with the intention of attending the Liberation Day ceremony. However, the arduous journey took a toll on his health. Just seven days after his arrival, on August 5, he succumbed to pneumonia while hospitalized in Seoul. His funeral, held on August 11, was the first social funeral for a foreigner in Korea, attended by President Syngman Rhee, who delivered a lengthy eulogy.

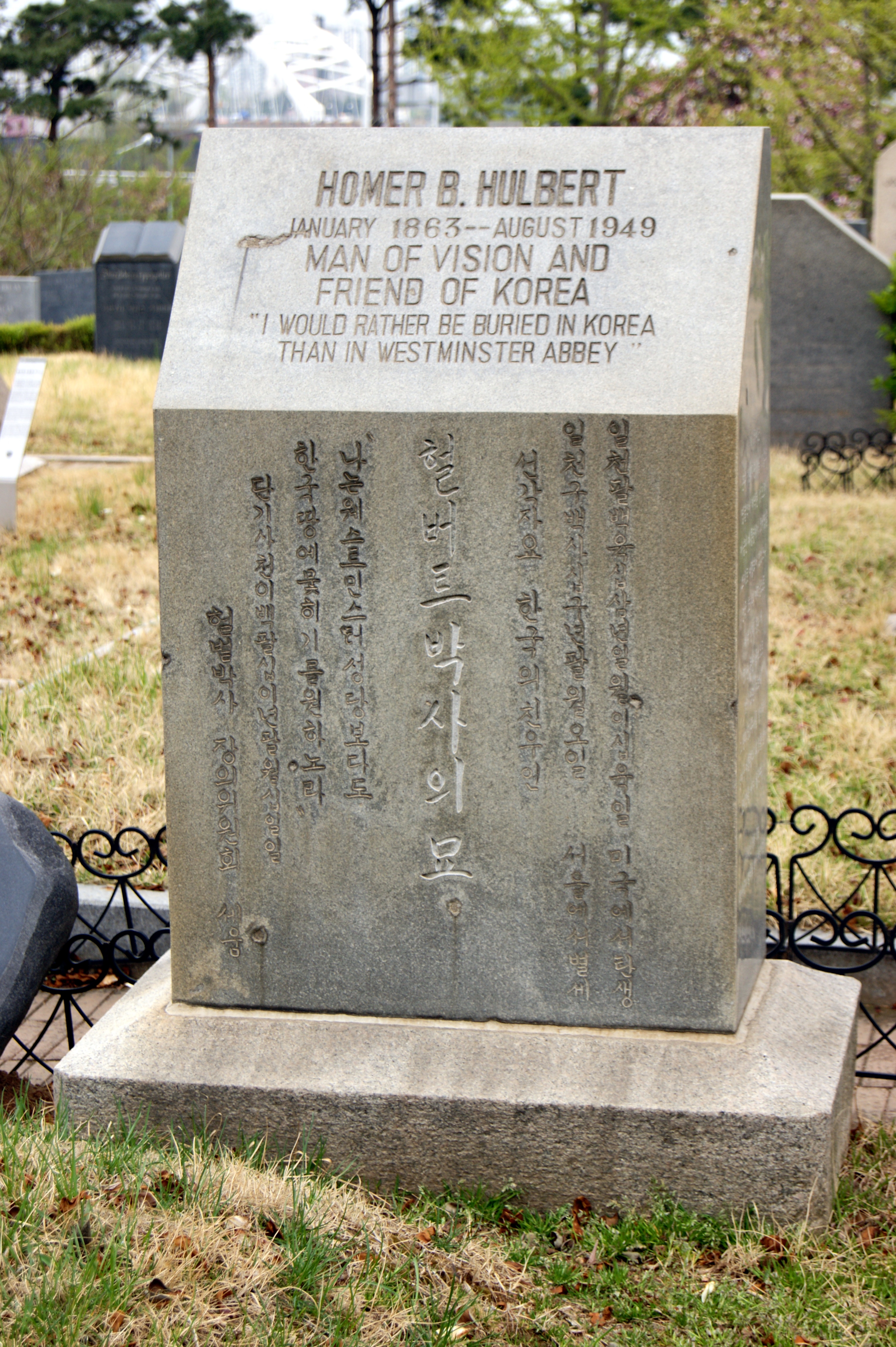

8.2. Last Will and Burial

Hulbert had often expressed his wish to be buried in Korea, the land he had loved in his youth. He famously stated, "I would rather be buried in Korea than in Westminster Abbey." This wish was honored, and he was interred at the Yanghwajin Foreigners' Cemetery in Seoul, where his first son, Sheldon, had already been buried.

Despite his lifelong dedication, Hulbert had two unfulfilled wishes at the time of his death: to see a unified Korea and to retrieve Emperor Gojong's secret fund. In 1903, Emperor Gojong had secretly deposited a significant amount of his private funds, estimated at 510.00 K DEM (German marks) in gold and Japanese yen, into the German-owned Deutsche Bank in Shanghai, entrusting Hulbert with the mission to retrieve it for Korea's independence movement. This was Hulbert's third secret mission from Gojong.

After his de facto expulsion by Japan in 1907, Hulbert briefly re-entered Korea in 1909 under the protection of the U.S. government, ostensibly to attend the 25th anniversary of Protestant missions in Korea. While arranging his affairs, he went to Shanghai to retrieve Gojong's funds. Despite presenting the bank manager's confirmation, Gojong's power of attorney, the German consul in China's certification, and the deposit receipt, he found the funds had been illegally withdrawn by the Japanese. Hulbert did not give up, hiring lawyers, confirming the withdrawal receipt written by Nabeshima, the first foreign affairs director of the Resident-General, and collecting related documents to submit a statement to the U.S. Congress. He continued his efforts to recover the money for 40 years, even sending a report and related documents to President Syngman Rhee in 1948 when he was over eighty. One of his purposes for returning to Korea in 1949 was to publicly expose Japan's illegal seizure of Gojong's independence funds and formally demand their return, thus fulfilling his promise to Gojong and his mission as a special envoy.

9. Legacy and Evaluation

Hulbert's enduring impact on Korea is profound, solidifying his place as a revered figure in Korean society and history.

9.1. Posthumous Awards from the South Korean Government

The South Korean government has bestowed numerous honors upon Homer B. Hulbert in recognition of his extraordinary contributions:

- In 1950, he was posthumously awarded the Order of Merit for National Foundation (Taegeukjang, or Independence Medal), making him the first foreigner to receive this honor.

- In 2009, the Mapo District of Seoul awarded honorary citizenship to his grandchildren, Bruce Hulbert and Margarets Hulbert.

- In July 2013, he was selected as the "Independence Activist of the Month" by the Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs, marking the first time a foreigner received this distinction. His great-grandson, Kimball Hulbert, also received honorary citizenship from Mapo District.

- On October 9, 2014, he was posthumously awarded the Order of Cultural Merit (Geumgwan), for his dedicated efforts in preserving and promoting Hangul.

- In 2015, he was honored with the first "Seoul Arirang Award" by the Seoul Arirang Festival Organizing Committee, recognizing his role in introducing the Korean folk song Arirang to the world.

9.2. Status in Korean Society

Hulbert is widely regarded in South Korea as one of the most beloved foreigners in its history, often ranked alongside the British journalist Ernest Bethell as a leading Western figure who actively worked to save Joseon during its late period. The independence activist An Jung-geun famously stated during his interrogation by Japanese police on December 2, 1909, "Koreans should not forget Hulbert for a single day." A statue of Hulbert stands in Seoul, the only such monument dedicated to an American civilian in the city. In 1999, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death, the epitaph "Dr. Hulbert's Tomb" was inscribed on his tombstone in Hangul, personally written by then-President Kim Dae-jung, fulfilling a long-standing wish after the space had remained empty for five decades.

9.3. Historical Influence

Hulbert's enduring influence is multifaceted. His scholarly work significantly contributed to the study of Hangul, advocating for its scientific excellence and promoting its use through textbooks and linguistic analyses. His efforts to introduce Hangul spacing and punctuation were crucial in its modernization. Beyond linguistics, he played a vital role in introducing Korean culture to the international community, notably by being the first to transcribe the traditional folk song Arirang into sheet music. His historical writings, particularly The Passing of Korea, provided critical insights into the Japanese occupation and served as an important record for understanding Korea's modernization and independence movements. His unwavering support for Korean sovereignty and his direct involvement in diplomatic efforts, such as the Hague Emissary Affair, cemented his legacy as a true champion of Korean self-determination.