1. Biography

Hideko Takamine's life and career were marked by an early start in the film industry, a successful transition from child stardom to leading actress, and a later career as a respected author. Her personal and professional journey was intertwined with major Japanese film studios and collaborations with renowned directors, culminating in a legacy of artistic excellence and social engagement.

1.1. Early Life and Childhood

Hideko Takamine was born on March 27, 1924, in Hakodate, Hokkaidō, as the eldest daughter of Kinji Hirayama and Iso. Her family's home was a soba noodle restaurant and teahouse called "Maruhira Sunaba," owned by her grandfather, Rikimatsu, who was a prominent local figure also managing the "Maruhira Theater" and "Maruhira Cafe." She had four brothers: Sanji, Seiji, Ryuzo, and Koichiro. At the age of four, following the death of her mother from tuberculosis, Takamine was adopted by her paternal aunt, Shige, who had previously been a female benshi (silent film narrator) under the name Hideko Takamine. Shige had eloped with a benshi named Ichiji Ogino at 17. After their benshi careers ended, Ichiji became a traveling show promoter, often leaving Shige to support the family through needlework. This early period saw Takamine facing significant financial burdens, with the livelihood of nine family members eventually resting on her shoulders after her grandfather's business went bankrupt in the Hakodate fire, prompting his family to move to Tokyo and rely on her.

1.2. Child Stardom

Takamine's acting career began serendipitously in September 1929 when her adoptive father took her to visit the Shochiku Kamata Studio, guided by Shoichi Nodera, an actor living downstairs. On that day, director Hōtei Nomura was holding auditions for child actors for his film Mother (Haha). Despite being a last-minute addition to the audition line, Takamine was chosen for the role of the daughter of the heroine, played by Yoshiko Kawada. She officially joined Shochiku Kamata Studio on October 1, adopting her aunt's former stage name, Hideko Takamine. The film, released on December 1, became a massive hit, enjoying a 45-day run in Asakusa and even an encore screening the following year. Her initial salary was 35 JPY, and the family soon moved closer to the studio in Kitakamata, Ebara District.

Takamine quickly became a sought-after child actress, earning the nickname "Deko-chan" from staff, who sometimes cast her in boy roles. She appeared in popular films such as Heinosuke Gosho's A Corner of Great Tokyo, Yasujirō Ozu's Tokyo Chorus, and Yasujirō Shimazu's Love with Humanity. Gosho was reportedly so impressed that he considered adopting her, but Shige opposed it. In 1931, she enrolled in an elementary school in Kamata but rarely attended due to her demanding filming schedule, which often involved all-night shoots. In April 1932, she was borrowed for a Shinpa play, Matsukaze Murasame, at the Meijiza theater, co-starring with Shōtarō Hanayagi and Yoshiko Okada. In the same production, she played the young Puyi in "Manchukuo," further solidifying her reputation as a child prodigy.

In 1934, lyricist Masato Fujita took a liking to Takamine, and she performed as Kantaro in a live stage show at the Hibiya Public Hall to celebrate Taro Shoji's hit song "Akagi no Komoriuta." Shoji was so fond of her that he insisted on adopting her, persuading her by promising intensive singing and piano lessons. Takamine and Shige moved into Shoji's home. However, Shoji's possessiveness meant Takamine was constantly with him, even on tour, and the promised lessons never materialized. Shige, treated as an unpaid maid, eventually prompted Takamine to leave Shoji's home, and they moved to an apartment in Oomori. This angered Fujita, who subsequently stopped writing songs for Shoji, instead giving his new songs like "Tsuma Koi Dochu" and "Oshidori Dochu" to newcomer Toshi Uehara.

In 1936, at the age of 12, as Shochiku moved its studio from Kamata to Shochiku Ofuna Studio, Takamine was transitioning from child roles to young female characters. She landed a significant role as the younger sister of the heroine, played by Kinuyo Tanaka, in Gosho's melodrama Shindo. Tanaka treated her like a real sister, and Takamine often stayed at Tanaka's luxurious home in Kamakurayama.

1.3. Studio Transitions

Feeling a desire to escape the film industry, Takamine considered joining the Takarazuka Revue. She consulted with Hanayagi Shotaro and Yaeko Mizutani, who helped her secure an offer for admission without an exam from Ichizō Kobayashi, the head of the Takarazuka Music School. However, in early 1937, she received an offer from Masumi Fujimoto of P.C.L. (Photo Chemical Laboratories), which would later become Toho. The terms included a monthly salary of 100 JPY, a house near the studio, and the opportunity to attend a girls' school. Takamine accepted, left Shochiku in January, and joined P.C.L. In April, she enrolled in Bunka Gakuin in Ochanomizu as promised.

Her first film with P.C.L. was The Chastity of a Husband, directed by Kajirō Yamamoto and based on a novel by Nobuko Yoshiya. She played Mutsumi, the younger sister of Kuniko, portrayed by Sachiko Chiba. She also co-starred with Ken'ichi Enomoto in Edokko Ken-chan. In September of the same year, P.C.L. became Toho Film Co., Ltd., and Takamine continued to appear in numerous films, becoming a beloved figure at the studio, affectionately known as "Deko." In 1938, she starred in Yamamoto's Tsuzurikata kyōshitsu (Composition Class), an adaptation of Masako Toyoda's best-selling collection of essays. Her portrayal of a strong and cheerful girl living in poverty became one of her earliest representative works. Due to her busy schedule, she attended Bunka Gakuin only two or three days a month and was eventually forced to withdraw after a year and a half.

At Toho, Takamine's popularity soared, and she appeared in nine films in 1939. Films were even named after her, such as Hideko's Cheering Squad Leader, for which she sang the theme song "Seishun Ground." However, the B-side song, "Kirameku Seiza," sung by Katsuhiko Haida, became a massive hit, selling 400,000 units. Her film Hideko the Bus Conductor (1941) marked her first collaboration with director Mikio Naruse, with whom she would later form a significant partnership. In 1940, she was deeply moved by Haruko Sugimura's performance as a leprosy patient in Shirō Toyoda's Spring on Leper's Island, which inspired her to take her acting career more seriously. She also studied vocalization under singers Ryōzō Okuda and Miho Nagato and performed for Japanese troops in war zones and for American occupation forces after the war.

In 1941, she starred in Yamamoto's Horse, a semi-documentary depicting the bond between a farm girl and her foal in rural Tohoku, which took three years to film. During its production, she fell in love with Akira Kurosawa, who was the production manager and director of the B-unit. Although their romance did not last due to her aunt's opposition, this episode was documented in her autobiography, Watashi no Tosei Nikki. In July 1945, while filming Yamamoto's America Yosoro in Tateyama, Chiba Prefecture, she experienced the end of World War II after a慰問 (comfort) performance at the Suzaki Air Corps. The production of America Yosoro, which dealt with kamikaze pilots, was subsequently canceled.

In 1946, Takamine's first postwar film was Kiyoshi Saeki's A Cheerful Woman. In August, she performed hula dance with Haida in "Hawaii no Yoru" at the Nippon Theater, which became a huge hit. However, in October, the second Toho labor dispute erupted. Takamine sided with Denjirō Ōkōchi, who opposed the strike, and along with Kazuo Hasegawa, Takako Irie, Isuzu Yamada, Susumu Fujita, Yatarō Kurokawa, Setsuko Hara, Toshiko Yamane, and Ranko Hanai, she formed the "Ten Flag Group" (Jūnin no Hata no Kai) and withdrew from the Toho Employees Union, which was under the umbrella of the Japan Film and Theater Workers Union. In March 1947, the Shintoho Film Production Company was established by these defectors, and Takamine became an exclusive actress for the new company. Her first film with Shintoho was Ryō Hagiwara's Oni of Oedo, followed by Yutaka Abe's Love with the Stars, in which she portrayed a woman's life from 16 to 35, and Taiji Chiba's Invitation to Happiness, where she played an unfortunate woman, solidifying her image as an adult actress.

During this period, the "Hideko Takamine Fan Club" was established, with an office in the Ginza Kanebo Building and a fan magazine called DECO. Within a year of Shintoho's founding, many of the "Ten Flag Group" members, including Setsuko Hara, Isuzu Yamada, and Takako Irie, left the company. This made Takamine the central figure among Shintoho's actresses. In 1949, she starred in Ginza Kankan Musume, for which she also sang the theme song. The record, released before the film, sold 500,000 units by 1957, becoming a major hit. In 1950, she played the youngest daughter in Abe's The Makioka Sisters, following Ranko Hanai, Yukiko Todoroki, and Toshiko Yamane. She maintained a close relationship with the original author, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, and his family until his death. In the same year, she appeared as the younger sister of Kinuyo Tanaka in Ozu's The Munekata Sisters. In November 1950, she left Shintoho after discovering that a company executive she was dating had embezzled fan club funds and was involved with another woman.

1.4. Freelance Career and Key Collaborations

In 1950, Takamine made the pivotal decision to become a freelance actress, a rare move for a major film star at the time. This decision allowed her to work with various studios and directors, unrestricted by the "Big Five Agreement" (Goshakyōtei) signed by film companies in 1953.

In 1951, she starred in Carmen Comes Home, Japan's first full-length color film, marking her first collaboration with director Keisuke Kinoshita. In June of that year, she traveled to Paris as a student, staying for six months. This period was a much-needed escape from her strained relationship with her aunt and the anxieties of her newfound freelance status, allowing her to enjoy freedom away from the film world. She returned to Japan in January 1952.

Her freelance status enabled her to appear in numerous films by master directors. She became particularly favored by Mikio Naruse, starring in 17 of his films between 1941 and 1966. These roles are widely considered "some of her finest performances," with her "sensitive yet resourceful persona" proving ideal for "Naruse's suffering, persevering heroines." Among her collaborations with Naruse were Lightning, where she excelled as the youngest of four siblings with different fathers but the same mother, and her acclaimed role in Floating Clouds (1955), where she portrayed a woman entangled with an unfaithful man. Other notable Naruse films include When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960), where she played a bar hostess in Ginza, and A Wanderer's Notebook (1962), portraying a young Fumiko Hayashi.

Film historian Donald Richie noted that the characters she played "wanted more out of life, but couldn't get it. The war may have been over, women found, but they weren't better off. They were still fairly unhappy. So the kind of roles Takamine played fit the zeitgeist, may have even made that zeitgeist." Takamine herself explained her approach to acting, stating, "Though different in style, they [Naruse and Kinoshita] shared a common aversion to things that were not natural. What I tried to do was to be as natural as women we see in the news, but adding a touch of drama so that I would be even more real."

Takamine also appeared in 12 films directed by Kinoshita. Her role as a new teacher on Shodoshima in Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) became one of her most iconic performances, earning her numerous acting awards. In Times of Joy and Sorrow (1957), she played a lighthouse keeper's wife alongside Keiji Sada, a film that became a major hit with its theme song. She also took on challenging roles such as a flawed wife in A Light in the Darkness (1957) and a peasant woman enduring harsh conditions during wartime in The River Fuefuki (1960), where she played characters ranging from 18 to 85 years old. In Immortal Love (1961), she portrayed a character from 20 to 49 years old, and in Years of Trial (1962), she played a road worker's wife, continuing her prominent roles as Kinoshita's heroine.

Beyond Naruse and Kinoshita, Takamine collaborated with other acclaimed directors, including Heinosuke Gosho on Where Chimneys Are Seen (1953), Shirō Toyoda on The Wild Geese (1953), Yōtarō Nomura on The Chase (1958), Hiroshi Inagaki on Rickshaw Man (1958), and Masaki Kobayashi on The Human Condition: A Soldier's Prayer (1961).

1.5. Marriage and Personal Life

On February 25, 1955, Hideko Takamine announced her engagement to Zenzo Matsuyama, who was then an assistant director under Kinoshita and whom she had met during the filming of Twenty-Four Eyes. The matchmakers were Matsutarō Kawaguchi and Aiko Mimatsu, along with Keisuke Kinoshita. Kinoshita, wanting to avoid gossip, personally called news agencies, stating, "This is Kinoshita from Shochiku. My Matsuyama and Hideko Takamine are getting married, so please come for an interview." This event is considered a pioneering example of a celebrity wedding press conference in Japan. Their wedding ceremony took place on March 26, 1955.

Despite her marriage, Takamine continued her acting career, stating her desire to "create a new style of wife who has a job." In 1961, she starred in Matsuyama's directorial debut, Happiness of Us Alone (Na mo Naku Mazushiku Utsukushiku), portraying a deaf-mute wife alongside Keiju Kobayashi. She delivered a remarkable performance, communicating entirely through sign language. She continued to star in Matsuyama's subsequent films, including I Am but a Grain of Wheat and Rokujo Yukiyama Tsumugi.

After 1965, her film appearances decreased, but she continued to deliver impactful performances, such as the mother of Seishū Hanaoka in Yasuzo Masumura's The Doctor's Wife (1967), starring Raizo Ichikawa VIII, and a devoted daughter-in-law caring for her senile father-in-law, played by Hisaya Morishige, in Toyoda's The Twilight Years (1973). She also began appearing in television dramas in 1968, including The Setting Sun Burns (1976), written by her husband Matsuyama, and episodes of Toshiba Sunday Theater. She also hosted the "Hideko Takamine Dialogue" segment on Fuji TV's "Ogawa Hiroshi Show." In October 1972, she appeared in the anti-war play The Catonsville Nine at Kinokuniya Hall.

In her personal life, Takamine and Matsuyama lived in a modest yet elegant house near Azabu-Juban, which was later downsized in their later years. She donated many of her film-related materials and trophies to memorial museums. She also owned a villa in Karuizawa, which she sold along with her antique collection in her later years. In her final years, she adopted Akemi Saito, a writer and editor for Bungei Shunju. Takamine was a heavy smoker, having started at age 22 for a role in the film Love with the Stars. She described herself as a "considerable chain smoker" in her book Oishii Ningen. Her death at 86 was due to lung cancer.

Takamine maintained close friendships throughout her life. She affectionately called Setsuko Hara "Onee-chan" (older sister) after they met at Toho. She was known for her playful teasing, once telling Meiko Nakamura's mother that "ugly children become cute when they grow up," only to later apologize when Nakamura blossomed, a memory Takamine herself had forgotten. She also taught Haruko Sugimura how to wash makeup puffs, a technique Sugimura passed on to her juniors, though Takamine had forgotten both the lesson and the technique. She was invited to Denjirō Ōkōchi's mountain villa, Ōkōchi Sansō, which was under construction and traditionally forbidden to women, due to their co-starring roles. Her long-standing friendship with director Kon Ichikawa began when he lodged at her home as an assistant director. She considered him a "comrade-in-arms" and actively defended him during the controversy surrounding the film Tokyo Olympiad. Takamine was also an avid antique collector, a hobby she picked up after seeking refuge in an antique shop from chasing fans. She had a long-standing friendship with antique dealer Seichosuke Nakajima, who called her "Ane-san" (big sister), and they even ran an antique shop together. The comedian Casey Takamine adopted his stage name from her, as he had a crush on her during the filming of Horse in Mogami, Yamagata Prefecture. She also developed a friendship with Empress Michiko after serving as a guest commentator for the live broadcast of the Imperial Wedding Parade in 1959, later selecting Empress Michiko as the "most beautiful woman in Japan" in a magazine discussion, emphasizing inner qualities over mere physical appearance.

1.6. Retirement and Literary Pursuits

In 1979, Hideko Takamine retired from acting after her final film, Kinoshita's Oh, My Son! (Shōdō Satsujin: Musuko yo). She had been asked to replace Yachie Kaoru, who withdrew from the project. At the press conference for the film, when asked if this would be her retirement, she replied, "I thought I had already retired." Her official announcement came during the film's production.

Following her retirement, Takamine primarily focused on her career as an essayist. Her acclaimed autobiography, Watashi no Tosei Nikki (My Life's Journey), was serialized in Shūkan Asahi starting in 1975. This book candidly recounted her life as a national actress and a woman, featuring real names of people she encountered. Its authenticity led to numerous inquiries, to which the editorial department responded, "If a ghostwriter were used, the writing wouldn't be so unique." The autobiography was published in two volumes by Asahi Shimbun in 1976 and became a bestseller, earning her the 24th Japan Essayists' Club Award.

Despite her limited formal schooling as a child actress, Takamine diligently cultivated her knowledge through reading scripts and extensive self-study. After marrying Matsuyama, she further honed her writing skills by transcribing his dictated screenplays at home. Her first book, Paris Hitori Aruki (Walking Alone in Paris), an essay collection detailing her six-month stay in Paris, was published in 1953. Other notable essay collections include Maimai Tsuburo, Watashi no Interview, Bin no Naka, and Ippiki no Mushi. She also co-authored travelogues with Matsuyama, such as Tabi wa Michizure Gandhara and Tabi wa Michizure Tutankhamen, and a cookbook, Daisho no Orchestra. In 2013, her adoptive daughter, Akemi Saito, discovered previously unpublished essays, which were released as Tabi Nikki Europe Futarisankyaku (Travel Diary: Europe Two-Legged Journey), a travelogue from her 1958 trip to Europe with her husband.

Beyond writing, Takamine remained involved in film in other capacities; she participated as an assistant director in Matsuyama's film Noriko, Now (1983) and wrote the script for the 1994 television drama Shinobazu no Onna. In 2003, she provided narration for the film Freddie the Leaf. Hideko Takamine passed away from lung cancer on December 28, 2010, at the age of 86, in a hospital in Shibuya, Tokyo.

2. Filmography

Hideko Takamine's extensive filmography spans over 50 years, showcasing her remarkable versatility and enduring presence in Japanese cinema. She appeared in a wide range of genres and collaborated with many of Japan's most celebrated directors.

| Year | Title | Role | Director(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | Mother (Haha) | Haruko | Hōtei Nomura | Film debut |

| 1930 | Review no Shimai | Hajime | ||

| 1930 | Dai Tokyo no Ikakku | Ichiro | Heinosuke Gosho | |

| 1930 | Reijin | Boy Iwao | ||

| 1930 | Chichi | Otsuna | ||

| 1930 | Shimai-hen Haha | Yukiko | ||

| 1931 | Watashi no Papa-san Mama ga Suki | Mitsuko | ||

| 1931 | Uruwashiki Ai | Ito's real daughter | ||

| 1931 | Love with Humanity (Ai yo Jinrui to Tomo ni Are) | Son Yasuo | Yasujirō Shimazu | |

| 1931 | Bōfūu no Bara | Koichi | ||

| 1931 | Onna wa Itsu no Yo nimo | Taro | ||

| 1931 | Shimai: Zenpen Kōhen | Ruiko | ||

| 1931 | Itarō ya Ai | Kinu | ||

| 1931 | Tokyo Chorus (Tokyo no Gassho) | Eldest daughter | Yasujirō Ozu | |

| 1931 | Reijin no Bishō | Yoichi | ||

| 1932 | Jōnetsu | Mitsuko's daughter | ||

| 1932 | Seven Seas: Part I. Virginity Chapter (Nanatsu no Umi: Zenpen) | Momoyo Sone | ||

| 1932 | Yōki na Ojōsan | Michiko | ||

| 1932 | Love Tied to Heaven (Tengoku ni Musubu Koi) | |||

| 1932 | Hototogisu | Michiko | ||

| 1932 | Nezumi Kozō Jirōkichi: Kaiketsu-hen | Tarokichi | ||

| 1933 | Hoho o Yose Sureba | Miyako | ||

| 1933 | Yotamono to Kaisuiyoku | Toshiyuki | ||

| 1934 | Tōyō no Haha | Shizuko's childhood | ||

| 1934 | Nukiashi Sashiashi | Toshiko | ||

| 1934 | An Inn in Tokyo (Sono Yo no Onna) | Shigeko | Yasujirō Ozu | |

| 1935 | Haha no Ai | Harue | ||

| 1935 | Eikyū no Ai | Hideko | ||

| 1936 | Shindo: Zenpen Akemi no Maki, Shindo: Kōhen Ryōta no Maki | Kyoko | Heinosuke Gosho | |

| 1937 | Hanayome Karuta | Kikue | ||

| 1937 | Hanagō no Uta | Hamako | ||

| 1937 | Ryōjin no Teiso | Mutsuko | Kajirō Yamamoto | |

| 1937 | Edokko Ken-chan | Mi-chan | ||

| 1937 | Misemono Ōkoku | Hiden-chan | ||

| 1937 | Shirobara wa Sakikedo | Flower shop girl | ||

| 1937 | Ojōsan | Unemployed teacher's daughter | ||

| 1938 | Composition Class (Tsuzurikata kyōshitsu) | Masako | Kajirō Yamamoto | |

| 1938 | Tōjūrō no Koi | Takeno-jō Uemura | ||

| 1938 | Niji Tatsu Oka | Yuri | Toshio Ōtani | |

| 1938 | Chocolate to Heitai | Shigeko | ||

| 1939 | Uruwashiki Shuppatsu | Natsuko | ||

| 1939 | Musume no Negai wa Tada Hitotsu | Hideko | ||

| 1939 | Roppa no Hohojiro Sensei | Hideyo | ||

| 1939 | Chūshingura | Aguri, maid at Ichiriki | ||

| 1939 | Ichiyō Higuchi | Midori Ōguroya | ||

| 1939 | Warera ga Kyōkan | Hideko | ||

| 1939 | Sono Zenya | Otsu | ||

| 1939 | Hanatsumi Nikki | Eiko Shinohara | ||

| 1939 | Shinpen Tange Sazen: Sekigan no Maki | Oharu | ||

| 1940 | Hideko no Ōendancho | |||

| 1940 | Soyokaze Chichi to Tomo ni | Hideko | ||

| 1940 | Tsuriganesō | Yumiko | ||

| 1940 | Enoken no Son Gokū | Princess | ||

| 1941 | The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday (Kinō Kieta Otoko) | Okyō | ||

| 1941 | Horse (Uma) | Ine Onoda | Kajirō Yamamoto | |

| 1941 | Awa no Odoriko | Omitsu | ||

| 1941 | Jogakusei Ki | Sachiko Kamata | ||

| 1941 | Hideko the Bus Conductor (Hideko no Shashō-san) | Okoma | Mikio Naruse | First film with Naruse |

| 1942 | Musashibō Benkei | Ushiwakamaru | ||

| 1942 | Kibō no Aozora | Hideko | ||

| 1942 | Matteita Otoko | Oyuki | ||

| 1942 | Genealogy of Women (Onna Keizu) | Taeko | ||

| 1943 | Ahen Sensō | Reiran | Masahiro Makino | |

| 1943 | Ai no Sekai: Yamaneko to Tomi no Hanashi | Tomi Odagiri | ||

| 1943 | Hanako-san | Chiyoko-san | ||

| 1943 | Hyōroku Yume Monogatari | Mysterious girl | ||

| 1943 | Wakaki Hi no Yorokobi | Yuko Takamura | ||

| 1944 | Obāsan | Maruko | ||

| 1944 | Sanjaku Sagohei | Otama | ||

| 1945 | Shōri no Hi made | |||

| 1945 | Kita no Sannin | Yoshie Matsumoto | ||

| 1946 | Yōki na Onna | Yoko Arai | Kiyoshi Saeki | |

| 1946 | Urashima Tarō no Kōei | Akako Tatsuta | ||

| 1946 | Those Who Make Tomorrow (Asu o Tsukuru Hitobito) | Takamine | Akira Kurosawa, Hideo Sekigawa, Kajirō Yamamoto | |

| 1946 | Aru yo no Tonosama | Taeko | Teinosuke Kinugasa | |

| 1946 | Toho Show Boat | Shoe-shining boy | ||

| 1947 | Toho Sen'ya Ichiya | Hideko Takayama | ||

| 1947 | Ōedo no Oni | Ryō Hagiwara | ||

| 1947 | Ai yo Hoshi to Tomo ni | Harue Shirakawa | Yutaka Abe | |

| 1947 | Kōfuku e no Shōtai | Hisa Shiina | Taiji Chiba | |

| 1948 | Aijō Shindansho | Akie | ||

| 1948 | Hana Hiraku: Machiko yori | Machiko Sone | ||

| 1948 | Sanbyaku Rokujūgo Ya | Ranko Komaki | ||

| 1948 | Niji o Daku Shojo | Akiko Hojo | ||

| 1949 | Haru no Tawamure | Ohana | ||

| 1949 | Good-Bye | Kinuko Nagai | ||

| 1949 | Ginza Kankan Musume | Oaki | Koji Shima | |

| 1950 | Shojo Hō | Makane | ||

| 1950 | Sasameyuki | Taeko | Yutaka Abe | |

| 1950 | The Munekata Sisters (Munekata Shimai) | Mariko | Yasujirō Ozu | |

| 1950 | Senka o Koete | Zhu Yan | ||

| 1950 | Sasaki Kojiro | Nami, Ryukyuan girl | ||

| 1951 | Onna no Mizukagami | Naeko | ||

| 1951 | Carmen Comes Home (Carmen Kokyō ni Kaeru) | Okin (Lily Carmen) | Keisuke Kinoshita | First film with Kinoshita |

| 1951 | Waga Ya wa Tanoshi | Tomoko, eldest daughter | Noboru Nakamura | |

| 1952 | Asa no Hamon | Atsuko Takimoto | ||

| 1952 | Tokyo no Ekubo | Kyoko Mine | ||

| 1952 | Inazuma | Kiyoko Komori | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1952 | Carmen's Pure Love (Carmen Junjōsu) | Carmen | Keisuke Kinoshita | |

| 1953 | Onna to Iu Shiro: Mari no Maki, Yuko no Maki | Mari Tsukiji | ||

| 1953 | Where Chimneys Are Seen (Entotsu no Mieru Basho) | Senko Higashi | Heinosuke Gosho | |

| 1953 | Asu wa Dotchi da | Mitsuyo | ||

| 1953 | Gan | Otama | Shirō Toyoda | |

| 1954 | Daini no Seppun | Shizuko Yamauchi | ||

| 1954 | The Garden of Women (Onna no Sono) | Yoshie Izushi | Keisuke Kinoshita | |

| 1954 | Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijūshi no Hitomi) | Hisako Ōishi | Keisuke Kinoshita | |

| 1954 | Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky (Kono Hiroi Sora no Dokoka ni) | Yasuko | Masaki Kobayashi | |

| 1955 | Floating Clouds (Ukigumo) | Yukiko Koda | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1955 | Wataridori Itsu Kaeru | Machiko | ||

| 1955 | Tōi Kumo | Fuyuko Terada | ||

| 1955 | Kuchizuke: Dai 3-wa "Onna Dōshi" | Tomoko Kaneda | ||

| 1956 | Shin Heike Monogatari: Yoshinaka o Meguru Sannin no Onna | Fuyuhime | ||

| 1956 | Kodomo no Me | Kiyoko | ||

| 1956 | A Wife's Heart (Tsuma no Kokoro) | Kiyoko Tomita | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1956 | Nagareru | Katsuyo | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1957 | Kumo no Bohyō yori: Sora Yukaba | Sachi | ||

| 1957 | Arakure | Oshima | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1957 | Times of Joy and Sorrow (Yorokobi mo Kanashimi mo Ikutoshitsuki) | Kiyoko Arisawa | Keisuke Kinoshita | |

| 1957 | Fūzen no Tomoshibi | Yuriko Sato | ||

| 1958 | Harikomi | Sadako Yokokawa | Yōtarō Nomura | |

| 1958 | Rickshaw Man (Muhōmatsu no Isshō) | Yoshiko Yoshioka | Hiroshi Inagaki | |

| 1960 | When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Onna ga Kaidan o Agaru Toki) | Keiko Yashiro | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1960 | Daughters, Wives and a Mother (Musume Tsuma Haha) | Kazuko Sakanishi | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1960 | The River Fuefuki (Fuefukigawa) | Okei | Keisuke Kinoshita | |

| 1961 | Happiness of Us Alone (Na mo Naku Mazushiku Utsukushiku) | Akiko Katayama | Zenzo Matsuyama | |

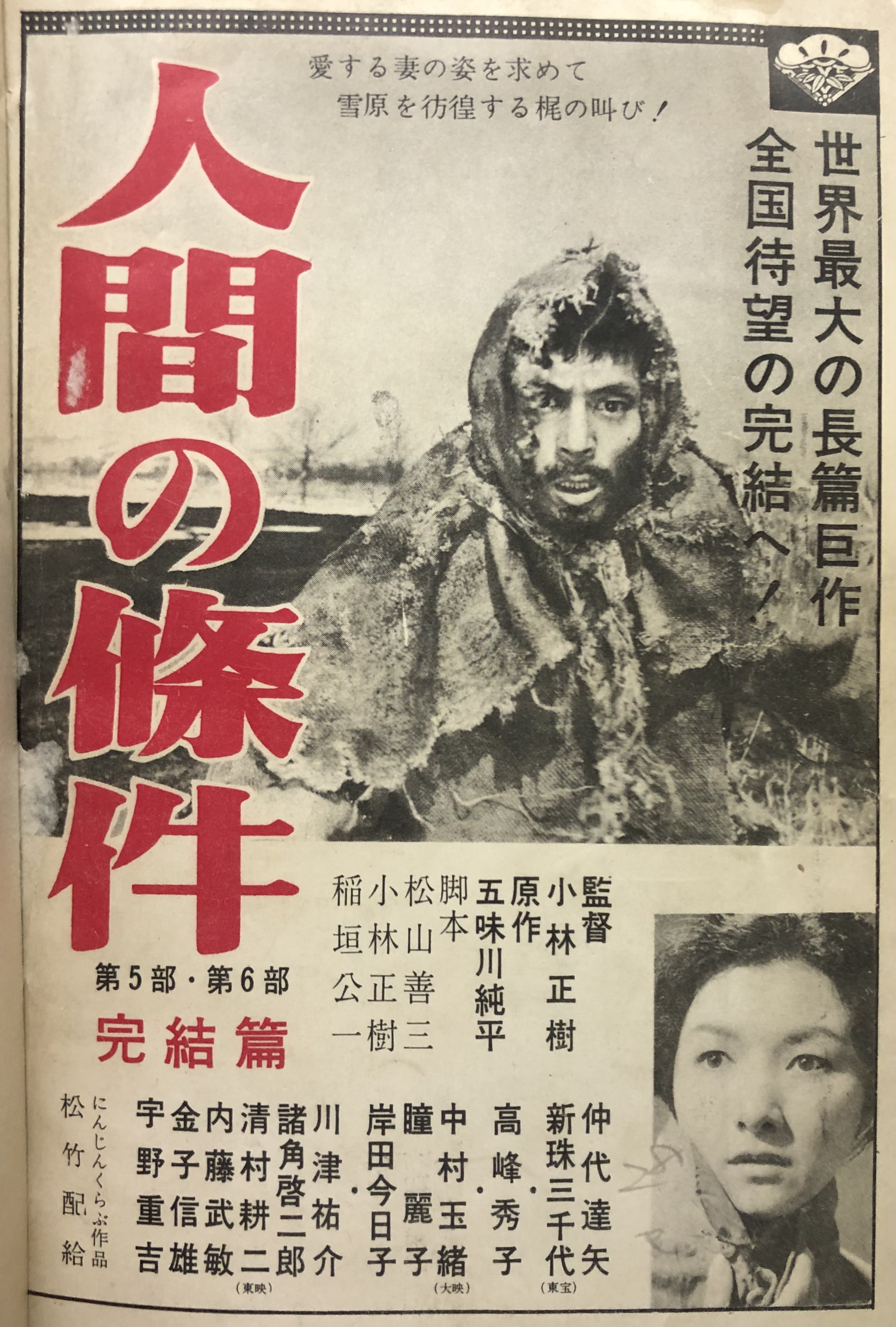

| 1961 | The Human Condition: A Soldier's Prayer (Ningen no Jōken: Dai 5-bu Dai 6-bu Kanketsu-hen) | Refugee woman | Masaki Kobayashi | |

| 1961 | As a Wife, As a Woman (Tsuma Toshite Onna Toshite) | Miho Nishigaki | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1961 | Immortal Love (Eien no Hito) | Sadako | Keisuke Kinoshita | |

| 1962 | Onna no Za | Yoshiko Ishikawa | ||

| 1962 | Sanga Ari | Kishino Inoue | ||

| 1962 | Futari de Aruita Ikutoshitsuki | Torae Nonaka | ||

| 1962 | A Wanderer's Notebook (Hōrōki) | Fumiko Hayashi | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1962 | Burari Burabura Monogatari | Komako Kuwata | Zenzo Matsuyama | |

| 1963 | Onna no Rekishi | Nobuko Shimizu | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1964 | Midareru | Reiko Morita | Mikio Naruse | |

| 1964 | Ware Ichitubu no Mugi Naredo | Noriko Nemoto | Zenzo Matsuyama | |

| 1965 | Rokujo Yukiyama Tsumugi | Ine Rokujo | Zenzo Matsuyama | |

| 1966 | Hikinige | Kuniko Bannai | ||

| 1967 | Zoku Na mo Naku Mazushiku Utsukushiku: Chichi to Ko | Akiko Katayama | ||

| 1967 | The Doctor's Wife (Hanaoka Seishū no Tsuma) | Otsugi | Yasuzo Masumura | |

| 1969 | Oni no Sumu Yakata | Kaede | ||

| 1973 | Kōkotsu no Hito | Akiko Tachibana | Shirō Toyoda | |

| 1976 | Sri Lanka no Ai to Wakare | Mrs. Jacaranda | ||

| 1976 | Futari no Ida | Kikue Sugawa | ||

| 1976 | Nakinagara Warau Hi | Yukiko Nakai | ||

| 1979 | Oh, My Son! (Shōdō Satsujin: Musuko yo) | Yukie Kawase | Keisuke Kinoshita | Final film |

3. Awards and Honors

Hideko Takamine received numerous awards and honors throughout her illustrious career, recognizing her exceptional contributions to Japanese cinema and literature.

- Japan Academy Film Prize**

- 1979: Outstanding Lead Actress for Oh, My Son!

- 1996: Chairman's Special Achievement Award

- 2011: Chairman's Special Award (posthumous)

- Mainichi Film Concours for Best Actress**

- 1954: For Twenty-Four Eyes, The Garden of Women, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky, Pleasure of Evil

- 1955: For Floating Clouds

- 1957: For Times of Joy and Sorrow, Untamed

- 1961: For Immortal Love, Happiness of Us Alone

- 2010: Special Award (posthumous)

- Blue Ribbon Award for Best Actress**

- 1954: For Twenty-Four Eyes, The Garden of Women, Somewhere Beneath the Wide Sky

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Actress**

- 1955: For Floating Clouds

- Asia-Pacific Film Festival (formerly Southeast Asian Film Festival) Best Actress Award**

- 1956: For Floating Clouds

- San Francisco International Film Festival Best Actress Award**

- 1961: For Happiness of Us Alone

- Arts Encouragement Prize**

- 1962: For Happiness of Us Alone, Immortal Love

- Locarno International Film Festival Best Actress Award**

- 1965: For Yearning

- Eidanren Lifetime Achievement Award**

- 1975: For long-term distinguished service

- Order of the Blue Ribbon (Konju Hosho)**

- 1975: For her donation of a portrait by Ryuzaburo Umehara to the Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art.

- Japan Essayists' Club Award**

- 1976: For Watashi no Tosei Nikki

- Japan Film Critics Award Golden Glory Award**

- 1994

- Film Day Special Achievement Award**

- 2011 (posthumous)

- Osaka Cinema Festival Special Award**

- 2011 (posthumous)

- Golden Gross Award Special Achievement Award**

- 2011 (posthumous)

4. Writings and Essays

Hideko Takamine's literary career was as distinguished as her acting, marked by a prolific output of essays and an acclaimed autobiography. Despite her limited formal education as a child actress, she cultivated her writing skills through extensive reading and by assisting her husband, Zenzo Matsuyama, with his screenplays.

Her first book, Paris Hitori Aruki (Walking Alone in Paris), an essay collection detailing her six-month stay in Paris, was published in 1953. This was followed by numerous other essay collections, including Maimai Tsuburo (1955), Watashi no Interview (1958), Bin no Naka (1972), Ippiki no Mushi (1978), Tsuzuri Kata Paris (1979), Ii Mono Mitsuketa (1980), Daisho no Orchestra (1982), Cotton ga Suki (1983), Ninjo Hanashi Matsutaro (1985), Oishii Ningen (1992), Shinobazu no Onna (1994), Ningen Nomi no Ichi (1997), Ningen no Oheso (1998), and Ningen Jūshoroku (2002).

Her most famous work is Watashi no Tosei Nikki (My Life's Journey), a two-volume autobiography serialized in Shūkan Asahi starting in 1975. This work was notable for its candid and direct recounting of her life, featuring real names of individuals she encountered. Its authenticity led to numerous inquiries, to which the editorial department responded, "If a ghostwriter were used, the writing wouldn't be so unique." The autobiography was published in two volumes by Asahi Shimbun in 1976 and became a bestseller, earning her the 24th Japan Essayists' Club Award.

She also co-authored several travelogues with her husband, Zenzo Matsuyama, including Tabi wa Michizure Gandhara (1979), Tabi wa Michizure Tutankhamen (1980), Tabi wa Michizure Aloha Oe (1982, later retitled Tabi wa Michizure Aloha Hawaii), and Tabi wa Michizure Setsugetsuka (1986). In 2013, her adoptive daughter, Akemi Saito, discovered previously unpublished essays from a 1958 trip to Europe with her husband, which were published as Tabi Nikki Europe Futarisankyaku (Travel Diary: Europe Two-Legged Journey). Takamine also penned an essay collection dedicated to her relationship with the painter Ryuzaburo Umehara, titled Watashi no Umehara Ryuzaburo (1987).

5. Other Activities and Interests

Beyond her celebrated careers in acting and writing, Hideko Takamine pursued various other interests and activities, showcasing her diverse talents and passions.

As a singer, Takamine had a notable presence, particularly in her early career. She released several records, including "Tabakoya no Musume" (1941), "Mori no Suisha" (1942), and "Utae Yamabiko" (1943). Her song "Ginza Kankan Musume" (1949), from the film of the same name, became a massive hit, selling 500,000 units. She also sang the theme song for Carmen Comes Home (1951). During World War II, she performed for Japanese troops in war zones, often without sound equipment, and later for American occupation forces in Tokyo.

Takamine was also a passionate painter and art collector. In 1949, during her time at Shintoho, she joined the Churchill-kai, an art appreciation society in Ginza. In 1950, she exhibited her painting "Midori-i" at the "Meishi Yogi Kaiga-ten" (Exhibition of Paintings by Notables) at Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi, where it sold for 4.70 K JPY. This led to her acquaintance with the master painter Ryuzaburo Umehara, with whom she maintained a close friendship for 40 years. Umehara painted numerous portraits of Takamine, with the first one created during the filming of Carmen Comes Home at his villa in Karuizawa. Takamine noted that Umehara struggled to capture her essence, initially making her eyes too large, before realizing it was her intense gaze rather than size that defined them. In March 1974, Takamine, at her husband's suggestion, donated her first portrait by Umehara to the Ryuzaburo Umehara Corner at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, for which she received the Order of the Blue Ribbon (Konju Hosho) and a wooden cup in 1975. In 1987, she published an essay collection, Watashi no Umehara Ryuzaburo, recounting her memories with the painter. In November 2005, Takamine herself donated 11 portraits, including seven by Umehara, one by Saburo Miyamoto, one by Motoko Morita, and two by Inshō Dōmoto, to Setagaya Ward, where they are now housed at the Setagaya Art Museum.

Her interest in antiques was also a significant part of her life. She developed a deep knowledge and passion for collecting antiques after seeking refuge in an antique shop in Ginza from persistent fans. She had a long-standing friendship with the renowned antique dealer Seichosuke Nakajima, who affectionately called her "Ane-san" (big sister). They even briefly co-owned an antique shop, an experience detailed in her autobiography Ningen Nomi no Ichi.

In television, Takamine hosted the "Hideko Takamine Dialogue" segment on Fuji TV's "Ogawa Hiroshi Show." She also appeared in various other television programs, including the "NHK Big Show" and "Hito ni Rekishi Ari" (People Have History), where she was featured in an episode titled "Hideko Takamine: Fifty Years of Acting, Her Long Journey." She also appeared in TV commercials for Tupperware (1963), Tanabe Seiyaku, Ajinomoto's "Hi-Me" (1980), and Kikkoman's "Sashimi Shoyu."

6. Artistic Philosophy

Hideko Takamine's artistic philosophy was rooted in a profound dedication to naturalism and an exceptional ability to portray complex characters with depth and authenticity. She was celebrated for breaking the "child actor to great actress" jinx, a common perception in both Japan and Hollywood, where many child stars struggled to transition successfully into adult roles.

Her approach to acting was characterized by a commitment to being "as natural as women we see in the news," while subtly "adding a touch of drama so that I would be even more real." This philosophy allowed her to inhabit a vast array of roles, making each portrayal distinct and believable. Unlike some actors whose personal charisma might overshadow their characters, Takamine had a rare ability to disappear into her roles, embodying the essence of each character without her own personality becoming a dominant feature. This "hundred-transformation" quality made her a singular figure in Japanese cinema history.

Takamine's roles evolved significantly from her early innocent portrayals to complex, multifaceted women in the postwar era. She played pioneering professional women, the nationally beloved teacher in Twenty-Four Eyes, a woman trapped in a destructive romantic relationship in Floating Clouds, a wife in a difficult marriage in Immortal Love, a strong deaf-mute woman navigating society in Happiness of Us Alone, a bar madam in Ginza in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, and a mistress in As a Wife, As a Woman. Her ability to convincingly embody such diverse characters, often spanning wide age ranges within a single film (e.g., 18 to 85 in The River Fuefuki), demonstrated her exceptional range and profound understanding of human nature.

Her dedication to her craft intensified after witnessing Haruko Sugimura's performance as a leprosy patient in Spring on Leper's Island (1940), which deeply impacted her and solidified her commitment to acting. She was known for her rigorous preparation and immersion in her roles. Her artistic vision was highly valued by directors like Mikio Naruse and Keisuke Kinoshita, who found her "sensitive yet resourceful persona" ideal for their nuanced portrayals of women. Takamine's legacy is defined by her remarkable versatility and her unwavering commitment to portraying authentic human experiences on screen, making her one of Japan's most revered and influential actresses.

7. Social and Political Engagement

Beyond her artistic contributions, Hideko Takamine was a figure who actively engaged with social and political issues, demonstrating a progressive stance and a commitment to human rights and societal improvement. Her actions reflected a deep sense of civic responsibility and a willingness to use her public platform for causes she believed in.

One notable instance of her political engagement occurred on June 4, 1960, when she participated in the central rally in Nagano Prefecture to protest the Anpo Treaty. While filming The River Fuefuki in Nagano City, Takamine, along with co-stars Takanobu Hata and Michiko Araki, and director Keisuke Kinoshita, joined members of the "Anti-Anpo Treaty Criticism Group." Standing on stage, Takamine declared, "I hate war. Everyone, please do your best," and subsequently led the demonstration march through the city, actively participating in the peace movement.

Takamine also critically engaged with media content. On February 10, 1971, she was invited as a witness (under her married name, Hideko Matsuyama) to the House of Representatives' Posts and Telecommunications Committee's "Subcommittee on Broadcasting." She voiced her concerns regarding the vulgarization of television programs and the escalating value of prizes in viewer-participation quiz shows. She famously stated that while violence and eroticism might be considered vulgar, "quiz shows where people win various things or go abroad... I think that falls into the lowest category of vulgarity." Her testimony contributed to a subsequent agreement in September of the same year between the Japan Fair Trade Commission and the National Association of Commercial Broadcasters in Japan to cap prize money and goods in quiz shows at 1.00 M JPY.

In the political arena, Takamine publicly supported progressive candidates. In the April 1967 Tokyo gubernatorial election, she endorsed Ryokichi Minobe, a prominent progressive politician who went on to become Governor of Tokyo.

She also demonstrated a strong commitment to defending artistic freedom and integrity. In 1965, when the film Tokyo Olympiad, directed by Kon Ichikawa, faced severe criticism from then-Minister of State for Olympic Affairs, Ichiro Kono, before its completion, Takamine publicly defended Ichikawa. She stated in magazines and newspapers that the film was "very beautiful and enjoyable," and criticized Kono's "violent words" calling Ichikawa's work "a stain on the Olympics," asserting that such remarks were unbecoming of a Minister of State. Takamine personally sought a meeting with Kono, where she passionately advocated for Ichikawa and the film's brilliance, urging Kono to meet with the director. Kono, who admitted to Takamine that he "didn't understand films at all," eventually met with Ichikawa. As a result of Takamine's mediation, Kono acknowledged the efforts of the production staff and ultimately allowed Ichikawa to retain editing rights for the international version, resolving the contentious dispute. Ichikawa later expressed deep gratitude for her intervention.

Furthermore, Takamine played a role in international cultural diplomacy and human rights advocacy. Before Japan established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, she and her husband were requested by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan to host a Chinese film delegation visiting Japan. When Zhao Dan, a major Chinese film star from the pre-war era, was imprisoned by Jiang Qing during the Cultural Revolution simply for knowing her during her acting days, Takamine consistently inquired about Zhao Dan's well-being through her contacts. Her persistent calls for his status are believed to have helped prevent his execution by the Cultural Revolutionaries, an episode detailed in her autobiographies Watashi no Tosei Nikki and Ippiki no Mushi. These actions underscore her commitment to human rights and her willingness to challenge injustice on an international scale.

8. Critical Reception and Legacy

Hideko Takamine's career was marked by consistent critical acclaim and immense public adoration, solidifying her status as a cultural icon and one of the most significant figures in Japanese cinema history. She famously defied the "child actor's jinx," a common belief that child stars rarely succeed as adult actors, by seamlessly transitioning from a child prodigy into a versatile and respected leading lady.

Critics and audiences alike lauded her remarkable range and ability to embody a vast spectrum of characters. From innocent young girls to complex, suffering women, independent career women, devoted wives, and even elderly figures, Takamine's performances were consistently praised for their depth and authenticity. She was noted for her unique ability to fully disappear into her roles, portraying diverse personalities without her own strong individuality overshadowing the character. This made her a rare "chameleon" actress in Japanese film history, capable of "a hundred transformations."

Her enduring legacy is reflected in numerous posthumous recognitions. In 2000, a poll by Kinema Junpo, Japan's oldest film magazine, named her the number one Japanese actress of the 20th century based on reader selections. This was reaffirmed in 2014 when Kinema Junpo again ranked her as the number one actress in their "All-Time Best Japanese Actors/Actresses" survey. Her dedication to cinema was so profound that she was often described as an actress who "debuted in film and retired from film," having very few stage appearances in her later years. Her contributions are seen as integral to the golden age of Japanese cinema, and her work continues to be studied and celebrated for its artistic merit and emotional resonance.

9. Posthumous Recognition

Hideko Takamine's enduring influence and memory within Japanese culture and the film industry have been celebrated through various posthumous tributes and projects.

On March 27, 2012, a memorial service was held for Hideko Takamine at Toho Studios, attended by approximately 400 industry figures, including actresses Yachie Kaoru, Kyoko Kagawa, Yoko Tsukasa, and Meiko Nakamura, as well as actors Akira Takarada and Masahiro Shinoda. At this event, the establishment of "Ippon no Kugi o Sanaeru Kai" (Praising a Single Nail) was announced, an award dedicated to recognizing behind-the-scenes staff who contribute to the film industry, fulfilling Takamine's lifelong wish to honor the unsung heroes of filmmaking.

In 2014, Kinema Junpo magazine, a leading authority on Japanese cinema, announced its "All-Time Best Japanese Actors/Actresses" list, where Hideko Takamine was ranked first in the actress category, further cementing her status as an unparalleled talent. This followed her previous top ranking in the magazine's "20th Century Film Stars" reader poll in 2000.

The year 2024 marked the 100th anniversary of Takamine's birth, prompting the launch of the "Hideko Takamine 100th Anniversary Project." As part of this project, a major special exhibition titled "The Aesthetics of Hideko Takamine: A Great Actress Who Overcame Adversity" was held at Tokyo Tower. The exhibition featured a wide array of her personal belongings, including handwritten manuscripts, illustrations, cherished possessions, and film posters, offering a comprehensive look into her life and career. Additionally, the National Film Archive of Japan hosted a special retrospective screening series titled "Hideko Takamine at 100," showcasing 22 of her most iconic films. Numerous other exhibitions, talk shows, and screenings were also organized across Japan to commemorate her life and work, underscoring her lasting impact on Japanese cinema and her cherished place in the nation's cultural memory.