1. Overview

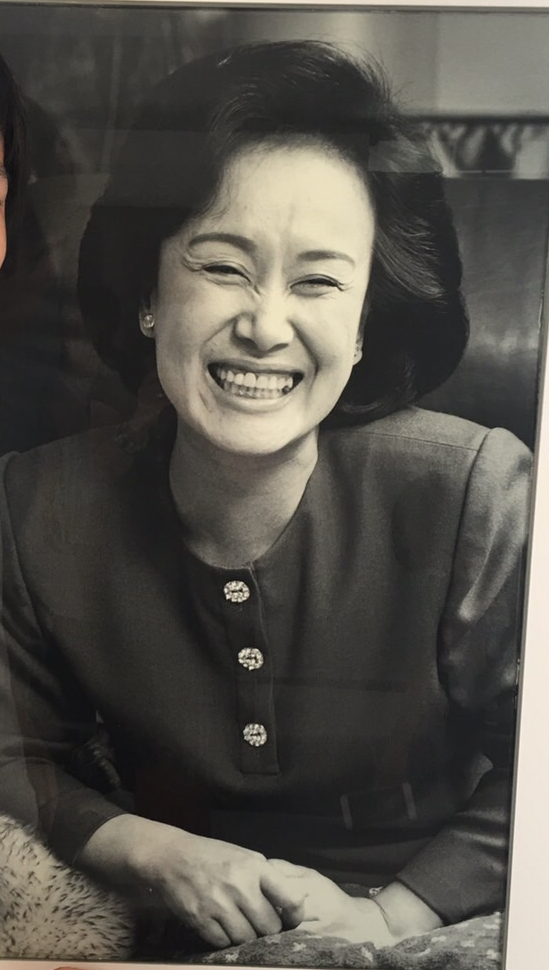

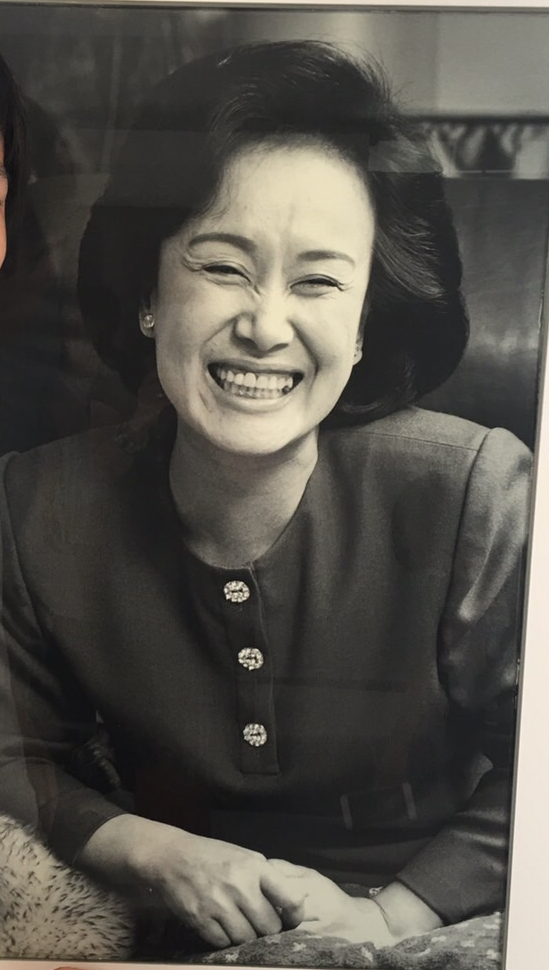

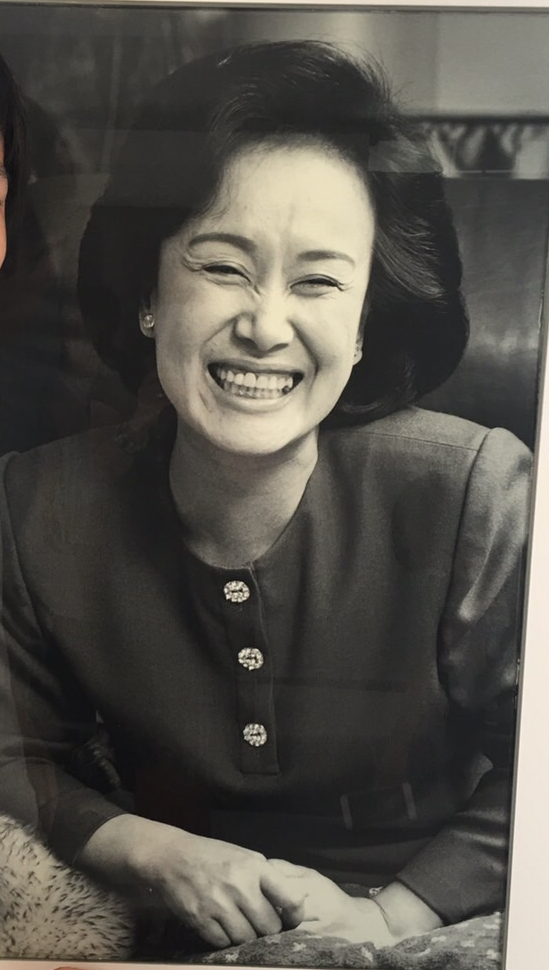

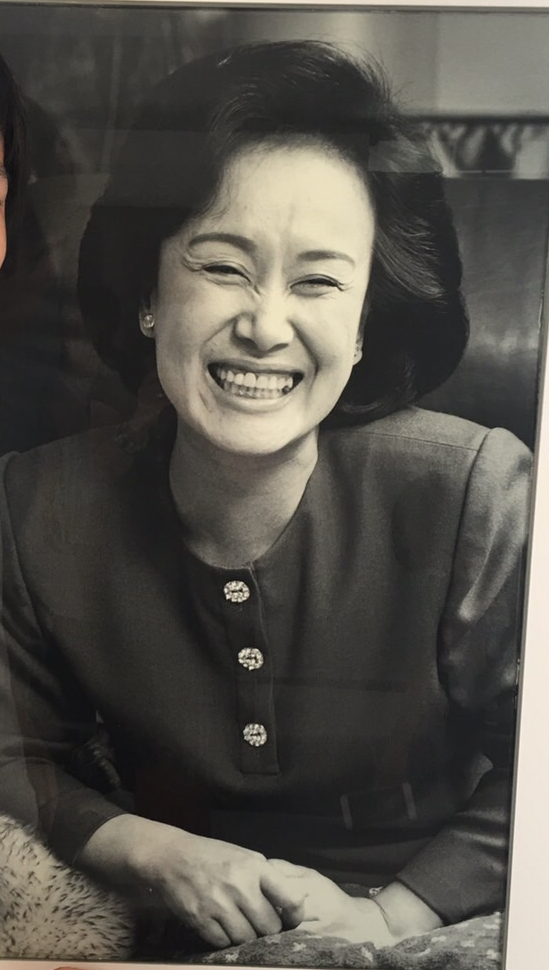

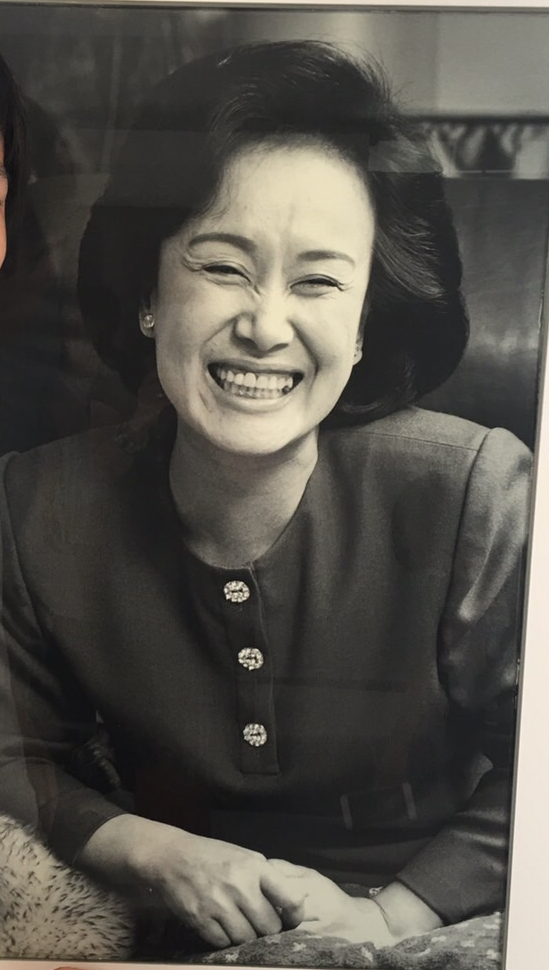

Hibari Misora (美空 ひばりMisora HibariJapanese, born 加藤 和枝Katō KazueJapanese on May 29, 1937 - June 24, 1989) was a legendary Japanese singer, actress, and cultural icon. Often hailed as the "Queen of Showa" and "Queen of the popular song," she captivated audiences with her prodigious vocal talent from a young age, making her debut at eight. Throughout her career, Misora recorded approximately 1,500 songs, with 517 original compositions, and achieved monumental record sales, surpassing 68 M copies by her death in 1989, and over 117 M by 2019. Her final single, "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", became an enduring classic, widely performed as a tribute. Misora was the first woman to receive Japan's prestigious People's Honour Award, conferred posthumously for her contributions to public welfare and for providing hope and encouragement after World War II. Her prolific career, spanning over four decades in music, film, and theater, solidified her status as an irreplaceable figure in Japanese popular culture, leaving an indelible mark on generations of artists and the national psyche.

2. Early Life and Family Background

Hibari Misora was born Kazue Katō on May 29, 1937, in Isogo-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. She was the eldest daughter of Masukichi Katō (1912-1963), a fishmonger who operated the "Uomasu" fish shop, and Kimie Katō, a housewife. Her father hailed from Toyooka Village (now Nikkō), Tochigi Prefecture, while her mother was from Sanya, Tokyo. She had a younger sister, Setsuko Sato, and two younger brothers, Tetsuya Katō and Takehiko Kayama. Both of her parents were avid music lovers and owned a phonograph, which exposed young Kazue to kayōkyoku and popular songs from an early age, fostering her enjoyment of singing.

Her innate musical talent became apparent during a send-off party for her father in June 1943, as he departed for military service in the Second World War. Six-year-old Kazue sang "九段の母Kudan no HahaJapanese" for him, moving the attendees to tears. Witnessing the profound emotional impact of her daughter's singing, her mother, Kimie, recognized Kazue's potential to captivate people. Kimie then began organizing慰問 (comfort) performances for Kazue in and around Yokohama. In 1945, at the age of eight, Kazue made her public debut at a concert hall in Yokohama. At her mother's suggestion, she adopted the stage name "Misora Kazue," with "Misora" (美空) literally meaning "beautiful sky."

There were some unsubstantiated claims that Misora and her family were Zainichi Koreans, holding Korean passports. However, after her death, writers Rō Takenaka and Tsukasa Yoshida investigated her family background and confirmed that she and her family were of pure Japanese descent.

3. Debut and Early Career

Following the war, Kimie continued her efforts to launch her daughter's singing career. Investing her personal funds, Kimie established her own "Aozora Gakudan" (Blue Sky Orchestra). Young Hibari performed on makeshift stages in local community centers and public bathhouses. In 1946, at the age of nine, Kazue entered the NHK "Shiroto Nodo Jiman" (Amateur Singing Contest) competition, singing "リンゴの唄Ringo no UtaJapanese" in the preliminary round. Despite the confidence of both Kazue and her mother, the judges did not pass her, citing her voice as "too mature" and "unsuitable for a child to sing adult songs," also criticizing her "bright red dress" as "uneducational."

Later that year, she performed at the Athena Theater in Yokohama, her first official stage appearance. The following spring, renowned Japanese composer Masao Koga, who was judging a "Nodo Jiman" competition in Yokohama, visited the Katō residence. He requested Kazue to sing for him. She performed his composition "悲しき竹笛Kanashiki TakebueJapanese" a cappella. Koga was deeply impressed by her talent, courage, and emotional maturity, stating, "You are no longer at the 'Nodo Jiman' level. You are already a mature singer." He encouraged her to pursue a professional singing career.

In 1947, Hibari performed as an opening act for the touring troupe of mandan artist Seiha Iguchi and zokkyoku singer Otomaru at the Sugita Theater in Yokohama. She officially joined their troupe, touring various regions. During a tour in Kōchi Prefecture on April 28, 1947, the bus carrying Hibari and her mother collided with an oncoming truck and plunged towards a ravine. Fortunately, the bus was caught by a single cherry tree, preventing a fatal fall into the Ananai River. Kazue sustained a cut on her left wrist, a nosebleed, and lost consciousness, appearing in a state of suspended animation with dilated pupils. A doctor from a nearby village provided life-saving treatment, and she regained consciousness that night. Upon returning home, her father, Masukichi, angrily demanded that she stop singing. However, Kazue firmly declared, "If I can't sing, I'll die!" She eventually returned to Tokyo, where she would begin her recording career in 1949.

In February 1948, during an appearance at the Kobe Shochiku Theater, she was introduced to Kazuo Taoka, the leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi, who held significant influence over entertainment in Kobe. Taoka took a liking to her. In May of the same year, Yoshio Kawada (later Haruhisa Kawada), a popular vaudeville artist and naniwabushi/kayōkyoku singer, recognized Hibari's hidden talent and took her under his wing as an apprentice. Hibari affectionately called Kawada "Aniki" (big brother) and learned much of her unique vocal phrasing (kobushi) from him, later stating that only her father and Kawada were her true mentors. At this time, Hibari's performances often mimicked the voice and expressions of the popular singer Shizuko Kasagi, earning her the nickname "Baby Kasagi." However, not all reception was positive; poet and lyricist Satō Hachirō criticized her in an article, stating, "Lately, there seems to be a low-quality child singer who imitates adults." Hibari and her mother kept this article for a long time, harboring resentment towards Satō, though they later reconciled.

In October 1947, Hibari joined the Shinpu Show theater troupe led by comedian Ban Junzaburō, performing with them and securing a semi-exclusive contract with the Yokohama International Theater. Her mother requested Keikichi Okada of the Takarazuka Revue to give her a stage name, and he bestowed upon her the name "Misora Hibari." Michihito Fukushima, the manager of the Yokohama International Theater, recognized her talent and became her manager, successfully planning numerous "Hibari films." It is believed that the name "Misora Hibari" was adopted by March 1948 at the latest, as evidenced by newspaper advertisements.

4. Rise to National Stardom

In January 1949, Hibari performed and danced in the Nichigeki revue "Love Parade," starring Katsuhiko Haida, where her renditions of Kasagi's songs like "Sekohan Musume" and "Tokyo Boogie Woogie" were well-received. In March of the same year, she made her film debut in Tōyoko Film's Nodojiman-kyō Jidai, singing boogie-woogie as a young girl. In August, she appeared in Shochiku's Odoru Ryūgūjō, and the film's theme song, "河童ブギウギKappa Boogie-WoogieJapanese", was released as the B-side of a Columbia Records single. This marked her official record debut on July 30, 1949, at the age of 11. The single became a commercial hit, selling over 450 K copies.

At the age of 12, she starred in the film Kanashiki Kuchibue (Sad Whistling), which became a massive hit. The accompanying theme song also sold 450 K copies, setting a new record at the time. Her image from this period, often depicted in a top hat and tailcoat, remains iconic. In 1950, Hibari traveled to the United States with Haruhisa Kawada for a fundraising performance to establish a memorial for the 100th Infantry Battalion Nisei unit. Upon their return, they starred in the film Tokyo Kid, which, along with its theme song, became another major hit. Her role as a street orphan in Tokyo Kid made her a symbol of both the hardships and the national optimism of post-World War II Japan.

In 1951, Hibari starred in Shochiku's Ano Oka o Koete (Cross That Hill), playing a character who admired a university student portrayed by the popular actor Kōji Tsuruta. In real life, Hibari also admired Tsuruta, affectionately calling him "Oniichan" (big brother). In May of the same year, Shin-Geijutsu Production (Shin-Gei Pro) was established, with Michihito Fukushima as president and Hibari, Haruhisa Kawada, and Torajiro Saito as executives. She also appeared as the boy Sugisaku in Shochiku's Kurama Tengu, a role she would reprise.

In 1952, her single coupling the theme song "リンゴ園の少女Ringo-en no ShōjoJapanese" and the insert song "リンゴ追分Ringo OiwakeJapanese" from the film Ringo-en no Shōjo became a huge hit, selling 700 K copies, setting a new record. After starring in Ojōsan Shachō (Madame Company President) in 1953, her mother Kimie began calling her "Ojō" (young lady), a nickname that was soon adopted by those around her.

On New Year's Eve 1954, Hibari made her first appearance on NHK's Kōhaku Uta Gassen. In 1955, she starred in the Toho film Janken Musume with Chiemi Eri and Izumi Yukimura. This film led to the formation of the popular singing trio "Sannin Musume" (Three Young Girls), who became stars in films produced by Shochiku and Toei Company. Their film fees varied significantly, with Hibari earning 7.50 M JPY per film, Eri 3.00 M JPY, and Yukimura 1.50 M JPY, making Hibari the highest-paid actress in the film industry at the time.

In 1956, Hibari was briefly engaged to jazz musician Mitsuru Ono, but the engagement was called off when she was told she would have to give up her career to marry. Her first performance in Naha, Okinawa (then under US administration), drew over 50,000 spectators in a week, with fans even traveling from remote islands, causing congestion at Naha Port.

On January 13, 1957, Hibari was attacked with hydrochloric acid at the Asakusa International Theater by a fanatical admirer. She was rushed to Asakusa Hospital and hospitalized for three weeks, but miraculously, no permanent scars remained on her face. This incident led her to request Kazuo Taoka to provide bodyguards, and she entrusted her performance rights to Kobe Geinō-sha. She returned to the stage at the Kabuki-za. On December 31, 1957, she made her second appearance on Kōhaku Uta Gassen, serving as the red team's final performer, surpassing veteran singers like Hamako Watanabe and Akiko Futaba, marking her golden age in the entertainment industry.

On April 1, 1958, Kazuo Taoka officially established Kobe Geinō-sha. Hibari became an exclusive artist of Kobe Geinō-sha in April of the same year. In July, she left Shin-Gei Pro, and on August 1, Hibari Production was founded, with Taoka assuming the role of vice president. On August 18, 1958, she signed an exclusive film contract with Toei. Toei subsequently produced 13 successful films featuring Hibari in their titles between the late 1950s and 1960s, including the "Hibari Torimono-chō" and "Beranmei Geisha" series. Her song "哀愁波止場Aishū HatobaJapanese" became a hit, earning her the 2nd Japan Record Award for vocal performance, solidifying her moniker as the "Queen of the popular song world."

5. Singing Career

Hibari Misora's musical career was exceptionally vast and impactful, cementing her status as a legendary figure in Japanese music. She recorded approximately 1,500 songs throughout her lifetime, with 517 original compositions. By the time of her death in 1989, she had sold 68 M records. This figure continued to climb posthumously, exceeding 80 M by 2001 and surpassing 100 M by 2019, with a total cumulative shipment of approximately 117 M physical media units as of May 1, 2019. This figure does not include digital sales.

Her musical style evolved significantly over her career, encompassing traditional enka, kayōkyoku, jazz, and even pop-oriented tracks. She was known for her incredible vocal range, emotional depth, and ability to master various genres.

Some of her most iconic and best-selling singles include:

- "柔YawaraJapanese" (1964): Her biggest hit, selling 1.8 M copies (later 1.95 M). It won her the 7th Japan Record Award.

- "悲しい酒Kanashii SakeJapanese" (1966): Sold 1.45 M copies (later 1.55 M).

- "真赤な太陽Makka na TaiyōJapanese" (1967): A pop-infused track with Jackie Yoshikawa and Blue Comets, selling 1.4 M copies (later 1.5 M).

- "リンゴ追分Ringo OiwakeJapanese" (1952): Sold 1.3 M copies (later 1.4 M).

- "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese" (1989): Her final single, selling 1.5 M copies (later 2.05 M). This song is often considered her magnum opus and swan song.

- "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese" (1987)

- "港町十三番地Minatomachi Jūsanban-chiJapanese" (1957)

- "波止場だよ、お父つぁんHatoba dayo, OtochanJapanese" (1956)

- "東京キッドTokyo KidJapanese" (1950)

- "悲しき口笛Kanashiki KuchibueJapanese" (1949)

Misora also collaborated with various artists and creators across different generations, including Nobuyasu Okabayashi (Tsuki no Yogisha, 1975), Takao Kisugi (Waratte yo Moonlight, 1983), Iruka (Yume Hitori, 1985), and Kei Ogura (Aisansan, 1986), showcasing her versatility and willingness to explore new musical territories.

She also penned lyrics for 22 songs during her lifetime, 18 of which she performed herself. Notable songs with her lyrics include Hana no Inochi, Taiyo to Watashi, Kiba no Onna, Romantic na Cupid, and Shinju no Namida, all of which were released as singles. She also wrote Yumemiru Otome (1966) for Mieko Hirota under her birth name, Kazue Katō, and three songs, Jūgoya, Katasezuki, and Lamp no Yado de, for her close friend Chiyoko Shimakura.

Misora was a regular and dominant presence on NHK's Kōhaku Uta Gassen, appearing 17 times and serving as the red team's final performer (Ōtori) an unprecedented 13 times, including 10 consecutive years (1963-1972), which remains an all-time record for any artist. In 1970, she also served as the red team's host, making her the first and only female artist in Kōhaku history to hold both roles simultaneously.

6. Acting Career

Hibari Misora was a prolific actress, starring in over 150 films between 1949 and 1971, with a total of 166 film appearances throughout her career. Her filmography is notable for its sheer volume and the diverse range of characters she portrayed. From 1949 to 1971, she typically appeared in 8 to 12 films annually, almost always receiving top billing.

Her roles spanned various genres, from light contemporary romances to period films featuring sword-fighting action. A recurring motif in many of her period films was her portrayal of male characters or female characters disguised as men. After concluding her film career, Misora occasionally continued to perform in male drag during her television appearances.

Her performance in Tokyo Kid (1950), where she played a street orphan, became symbolic of both the hardships and the national optimism that characterized post-World War II Japan. Other notable early films include Nodojiman-kyō Jidai (1949), her debut, and Kanashiki Kuchibue (1949), which became a major hit. She also famously played the boy Sugisaku in the Kurama Tengu series, starting with Kurama Tengu, Kakubeijishi (1951).

Misora's films were consistently popular, contributing significantly to the golden age of Toei's period dramas. She signed an exclusive contract with Toei in 1958, and during her 10-year exclusive period with the studio (until 1963), she starred in 102 Toei films. Her presence in a film, especially those with "Hibari" in the title (47 films, a national record), guaranteed box office success. Despite her films rarely receiving major artistic awards, they consistently delivered entertainment, and her fans celebrated her dedication to popular cinema. She was recognized for her immense popularity with the Blue Ribbon Award for Popularity in 1961, acknowledging her 13 years of being loved and cherished by the public.

Her acting credits include:

- Nodojiman-kyō Jidai (1949)

- Odoru Ryūgūjō (1949)

- Kanashiki Kuchibue (1949)

- Tokyo Kid (1950)

- Aozora Tenshi (1950)

- Kurama Tengu: Kakubējishi (1951)

- Haha wo Shitaite (1951)

- Ano Oka Koete (1951)

- Yōki-na Wataridori (1952)

- Ringo-en no Shōjo (1952)

- Ushiwakamaru (1952)

- Ojōsan Shachō (1953)

- Izu no Odoriko (1954)

- Yaoya Oshichi Furisode Tsukiyo (1954)

- Janken Musume (1955)

- Takekurabe (1955)

- Romance Musume (1956)

- Ōatari Sanshoku Musume (1957)

- Ōatari Tanukigoten (1958)

- Hibari Torimonochō: Kanzashi Koban (1958)

- Chūshingura: Ōka no Maki, Kikka no Maki (1959)

- Beranmē Geisha (1959)

- Samurai Vagabond (1960)

- Hibari no Mori no Ishimatsu (1960)

- Sen-hime to Hideyori (1962)

- Hibari no Hahakoi Guitar (1962)

- Hibari, Chiemi, Izumi: Sannin Yoreba (1964)

- Noren Ichidai: Jokyo (1966)

- Gion Matsuri (1968)

- Hibari no Subete (1971)

- Onna no Hanamichi (1971)

7. Personal Life and Relationships

Hibari Misora's personal life was marked by deep family bonds, public scrutiny, and significant losses. Her mother, Kimie Katō, was an exceptionally influential figure in her life, serving not only as her devoted parent but also as her primary producer and manager throughout her career. Their closeness was so profound that they were often referred to as "one-egg parents" by the media. Kimie's influence extended to Hibari's romantic life, as she openly expressed her disapproval of Hibari's marriage to actor Akira Kobayashi, later stating that the unhappiest moment of her life was her daughter's marriage to Kobayashi, and the happiest was their divorce.

In 1956, Hibari was briefly engaged to jazz musician Mitsuru Ono, but the engagement was called off due to the condition that she would have to give up her career to marry.

In 1962, Hibari married Akira Kobayashi, a top actor from Nikkatsu. Their marriage, however, was short-lived, ending in divorce in 1964 after just two years. Although Kobayashi desired to formally register their marriage, Kimie consistently refused, citing concerns about property disposition. Consequently, Hibari remained legally single throughout her life. The constant interference from her mother and other associates, coupled with Hibari's reluctance to fully abandon her career, contributed to the marriage's dissolution. Kobayashi later recalled that Hibari tried her best to be a good wife, describing her as "the best as a woman." The term "understanding divorce" became a buzzword after their separate press conferences. Kobayashi expressed deep regret, stating he wished he could cry in front of everyone, as the divorce was not his true intention. Hibari, accompanied by Kazuo Taoka, stated that revealing the reasons would hurt both parties and that she chose the path to her own happiness, emphasizing her inability to abandon her art or her mother.

A year after her marriage, in 1963, her father, Masukichi, passed away at the age of 52 from pulmonary tuberculosis.

In 1973, Hibari faced a major controversy when her younger brother, Tetsuya Katō, was arrested for gang-related activities. Tetsuya, who had debuted as a singer under the stage name Ono Tōru in 1957, became a senior member of the Masuda-gumi, a branch of the Yamaguchi-gumi. He had a history of arrests for gambling, illegal firearm possession, assault, and smuggling. This incident brought to light the Katō family's ties with the Yamaguchi-gumi and its leader, Kazuo Taoka, who was also involved in Hibari's management. As a direct consequence, many public venues refused to host her performances if her brother was involved, leading to widespread media criticism. This led to her exclusion from NHK's prestigious Kōhaku Uta Gassen for the first time in 18 years, effectively a ban. Offended by this, Misora refused to appear on any NHK programs for several years, though she eventually made peace with the broadcaster, appearing as a special guest on the 1979 Kōhaku, which was her final appearance on the program.

In 1978, Hibari adopted her seven-year-old nephew, Kazuya Katō, Tetsuya's son.

The 1980s proved to be an incredibly difficult period for Hibari due to a series of profound personal losses. Her beloved mother, Kimie, passed away in 1981 at the age of 68 from metastatic brain tumor. Her 35th-anniversary recital at the Nippon Budokan that year was held while Kimie was in critical condition. Her father figure, Kazuo Taoka, also died shortly after. In 1982, her close friend and fellow singer/actress, Chiemi Eri, died suddenly at 45. Her two younger brothers, Tetsuya and Takehiko Kayama, both died young at 42 in 1983 and 1986, respectively. To cope with her immense sorrow and loneliness, Hibari, already known for her heavy drinking and smoking, increased her consumption, which began to severely impact her health.

Hibari maintained deep friendships with many prominent figures across entertainment, sports, and politics. She was particularly close to Sadaharu Oh, whom she considered a "brother," and also had strong ties with Masaichi Kaneda. She was also a mentor to comedian Shinji Maki and had a unique relationship with the comedy duo Tunnels, whom she affectionately called "Taka" and "Nori," treating them like younger brothers.

8. Health Struggles and Later Years

The demanding nature of Hibari Misora's career, coupled with her increasing reliance on alcohol and cigarettes to cope with personal tragedies, took a severe toll on her health in the 1980s. In May 1985, during a golf competition celebrating her birthday, she twisted her lower back, experiencing sharp, pulling pains in both inner thighs. She began complaining of unexplained lower back pain, which gradually worsened, though she continued to perform with unwavering passion, showing no signs of discomfort. In 1986, she held her 40th-anniversary recitals in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. However, by February 1987, during her Shikoku tour, the pain in her legs became unbearable.

Despite her deteriorating health, she visited Toba City in Mie Prefecture to see the sea otters at Toba Aquarium, a personal request. She also filmed a karaoke video there. During a retake, she struggled to step over a small rise and needed assistance to walk, completing the shoot with help from her attendant. Footage from this period, showing her walking with difficulty, is still used in karaoke videos for songs like "Ringo Oiwake" and "Makka na Taiyō."

On April 7, just two weeks before her hospitalization, she appeared on Nippon TV's "Columbia Enka Daikōshin," where she was visibly unwell and had to be assisted by Takashi Hosokawa and Chiyoko Shimakura to enter. Despite her condition, she sang "Aisansan" and other songs.

On April 22, 1987, while on tour in Fukuoka, she suddenly collapsed due to extreme ill health and was emergency-hospitalized at Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital. She was diagnosed with severe chronic hepatitis and bilateral idiopathic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Although her actual condition was cirrhosis, this was kept secret from the press to avoid alarming her fans and associates. Her scheduled May performance at the Meiji-za was canceled. On May 29, her 50th birthday, while still hospitalized, she released a voice message to the media and fans, stating, "I am diligently following my doctors' instructions as a model patient. No need to rush, just a little rest."

Amidst the deaths of close friends and Showa-era stars like Kōji Tsuruta (June 16, 1987) and Yujiro Ishihara (July 17, 1987), Hibari was discharged from the hospital on August 3. She greeted her waiting fans with a smile and a flying kiss. At the press conference, she tearfully expressed her unwavering belief in singing again, concluding with a smile, "I will quit alcohol, but I will not quit singing." After two months of home recuperation, she resumed her entertainment activities on October 9 with the recording of her new song "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese."

However, her illness was far from cured. Her liver function had only recovered to about 60% of normal, and the avascular necrosis was deemed difficult to heal. Her health continued to decline, making it difficult for her to even climb stairs alone, requiring a lift to get onto stages.

On April 11, 1988, Hibari held her legendary "Fushichō Concert" (Phoenix Concert) at the newly opened Tokyo Dome. Despite overwhelming pain in her legs and her liver function fluctuating between 20-30%, she performed a total of 39 songs. The audience was unaware of her true condition; backstage, she lay on a bed with an oxygen tank. Celebrities like Mitsuko Mori, Izumi Yukimura, Chiyoko Shimakura, Ruriko Asaka, and Kayoko Kishimoto attended to support her. Ruriko Asaka described her dressing room as resembling a hospital room, recalling Hibari's brave smile and her words, "I'm not okay, but I'll do my best." After her final song, "人生一路Jinsei IchiroJapanese", she slowly walked the 328 ft (100 m) flower path, her face contorted in pain, yet waving to fans. Upon reaching the end, she collapsed into her adopted son Kazuya's arms and was immediately taken away by an ambulance on standby. While the media reported a "complete comeback," it was a performance that cost Hibari her life force.

Her health continued to worsen after the Tokyo Dome concert. She could no longer climb stairs unaided and required lifts for stage entrances. Despite this, she continued to work tirelessly, including recording for her final original album, Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni ~ Fushichō Part II, with young creators like Yasushi Akimoto and Akira Mitake. Her staff initially planned to release "ハハハHahahahaJapanese" as a single, but Hibari passionately insisted on "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", stating, "Please, just this once, indulge my selfishness!" This song, released on January 11, 1989, became her final single.

On December 12, 16, and 17, 1988, she recorded her final one-woman show, "Haru Ichiban! Netshō Misora Hibari," for TBS, which aired on January 4, 1989. Despite her severe pain and breathlessness, she performed mostly seated. At the end, she thanked the staff and guests, saying, "Hibari will continue to sing as much as possible. Because it's the path I chose." She also teared up after receiving words of encouragement from Shigeharu Mori. Her final TV drama appearance was a cameo in "Papa wa News Caster" on January 2, 1989.

By this time, the symptoms of interstitial pneumonitis, her direct cause of death, had already begun. On December 25 and 26, 1988, she held her final Christmas dinner show at the Imperial Hotel, attended by friends like Fukuko Ishii and Sadaharu Oh. Despite her struggles, she performed a vigorous twist, delighting the audience. Ishii later recounted how Hibari, unannounced, appeared at a restaurant where she and Oh were dining after the show and sang a naniwabushi, leaving Ishii deeply moved.

9. Death and National Mourning

On January 8, 1989, as the Japanese era transitioned from Showa to Heisei, Hibari penned a tanka poem: "Heisei no ware shinkai ni nagaretsuki inochi no uta yo odayaka ni..." (In the Heisei era, I flow to a new sea, may my song of life be peaceful...). Just three days later, on January 11, her final single, "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", was released, though her lungs were already severely affected by illness.

She made her last television appearances on Enka no Hanaji and Music Fair on January 15, singing "Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni" and other songs. Her condition continued to deteriorate. A few days before a concert in Fukuoka, she was informed by a doctor that her condition was worsening. Despite strong opposition from those around her, she insisted on performing the concert on February 6 at Fukuoka Sunpalace, where she experienced cyanosis due to worsening cirrhosis. She pushed through, performing the next day, February 7, at Kyushu Koseinenkin Kaikan in Kokura, which became her final stage performance. Due to her extreme weakness, she traveled by helicopter and rested backstage with an oxygen tank, facing the risk of esophageal varices rupture. Her adopted son Kazuya recalled her performing solely on willpower, as doctors warned of imminent collapse. She could not even step over a small rise to the stage alone. She performed 20 songs, mostly seated, concealing her severe idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis.

After her final concert, she was hospitalized for examination at Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital on February 8. After a temporary discharge, she stayed at a friend's home in Fukuoka until late February, returning to Tokyo by helicopter. Her physical strength was completely depleted. Days of home recuperation followed, and despite the cancellation of her nationwide tour, she remained determined to perform at the opening concert of Yokohama Arena, her hometown, on April 17. She adamantly stated, "I want to stand on the Yokohama Arena stage. I will crawl if I have to for this performance!" Her son Kazuya, concerned for her health, urged her to cancel, leading to frequent arguments.

Around this time, a doctor introduced by Fukuko Ishii examined Hibari, noting her blue fingertips and pale face, and strongly recommended hospitalization. On March 9, after a long silence, Hibari tearfully accepted the decision to be re-hospitalized. She was temporarily discharged after further tests and made her final media appearance on March 21, a 10-hour live radio special for Nippon Broadcasting System from her home, where she stated, "Hibari will never retire. I will keep singing and then disappear without anyone noticing." Immediately after the broadcast, her condition worsened, and she was re-hospitalized at Juntendo University Hospital in Tokyo.

Two days later, on March 23, her son Kazuya announced the cancellation of all her concerts, including the Yokohama Arena opening, and a year-long hiatus from all entertainment activities, citing "worsening allergic bronchitis" and "intractable cough" (the actual diagnosis of interstitial pneumonitis was not revealed to the public or to Hibari herself, though she had been informed of it by a doctor in early March).

On May 27, while hospitalized, Hibari released a message to the media along with a photo, stating, "A lark flies from a wheat field... Do not shoot that bird, villagers!" She also released a recorded voice message, expressing her desire to live without regrets. However, her voice was weak and strained compared to her previous hospitalization. This was her final message and recorded voice released to the public.

Two days later, on May 29, Hibari celebrated her 52nd birthday in the hospital. Her sister Setsuko Sato recalled Hibari crying and asking, "Setsuko, can I still live?" to which Setsuko replied, "What are you saying? You're only 52! You have to keep living!" Hibari then said, "You're right, I can't die and leave Kazuya alone. I'll do my best."

Fifteen days after her birthday, on June 13, she experienced severe respiratory distress and was placed on a ventilator. Her last words to the Juntendo Hospital medical team were reportedly, "Thank you. I'll do my best." Kazuya later recounted that a few days before her death, when he encouraged her, she had tears in her eyes, as if she had accepted her fate.

On June 24, 1989, at 0:28 AM, 136 days after her last stage performance and three months after her re-hospitalization, Hibari Misora died at Juntendo University Hospital due to respiratory failure caused by worsening idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis. She was 52 years old. Her death was widely mourned across Japan, and many felt that the Showa period had truly come to an end with her passing. Major television networks canceled their regular programming that evening to broadcast news of her death and air various tributes.

Her wake was held on June 25, followed by her funeral at her residence on June 26, attended by numerous figures from the entertainment, sports, and political worlds. As her hearse left her home, many fans lined the streets to mourn her passing. On July 22, her funeral at Aoyama Funeral Hall in Tokyo attracted a record 42,000 attendees. Kazuya served as chief mourner, and eulogies were delivered by Kinnosuke Yorozuya, Shigeharu Mori, Meiko Kaji, Sadaharu Oh, and Takaaki Ishibashi of Tunnels. Fellow singers like Saburō Kitajima, Izumi Yukimura, Masako Mori, Fumiya Fujii, and Masahiko Kondō sang "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese" in tribute. Her posthumous Buddhist name is Jishōin Misora Nichiwa Seitai-shi. Her grave is located at Hino Public Cemetery in Konan Ward, Yokohama.

10. Legacy and Cultural Impact

Hibari Misora's death did not diminish her immense influence; rather, it solidified her status as an "eternal diva" and cultural icon in Japan. Her legacy continues to resonate deeply through annual television and radio specials dedicated to her music, particularly her swan song, "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese." In a 1997 national poll by NHK, this song was voted the greatest Japanese song of all time by over 10 million people. It has been notably performed as a tribute by international artists such as The Three Tenors, Teresa Teng, Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán, and the Twelve Girls Band.

Posthumous tributes and commemorations abound:

- Memorial Monuments**: In April 1993, a monument featuring Misora's portrait and an inscribed poem was erected near Sugi no Osugi in Ōtoyo, Kōchi. This location holds special significance as a 10-year-old Misora, recovering from a severe bus accident there in 1947, reportedly visited the ancient cedar tree and wished to become Japan's top singer. Her father had wanted her to quit singing after the accident, but she famously declared, "If I can't sing, then I will die." In Iwaki City, Fukushima Prefecture, the setting of her hit song "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese", a song monument was erected on October 2, 1988, followed by a memorial portrait monument on May 26, 1990. The surrounding 1378 ft (420 m) of road was developed as "Hibari Kaidō" (Hibari Road) in 1998, and a bronze statue titled "Eternal Hibari" was erected on May 25, 2002. In October 2024, a bronze statue from the former Kyoto Uzumasa Hibari-za was relocated to Iwaki, further solidifying the site as a place of remembrance.

- Museums and Memorial Halls**: The Hibari Misora Museum opened in Arashiyama, Kyoto, in April 1993, showcasing her personal belongings and career history. After attracting over 5 million visitors, it closed in 2006 for renovation. It reopened as the Hibari Misora Theater in April 2008, and later, in October 2013, a new "Kyoto Uzumasa Hibari-za" opened within the Toei Uzumasa Eigamura, displaying approximately 500 items, including stage costumes and restored film posters. In May 2014, the "Tokyo Meguro Hibari Memorial Hall" opened, converting a part of her former residence in Meguro, Tokyo, into a public museum.

- Posthumous Releases and Events**:

- Her unreleased song "流れ人NagarebitoJapanese", recorded for a 1980 stage play, was released as her first posthumous single in 1999. In 2016, another unreleased recording, "さくらの唄Sakura no UtaJapanese", was released.

- Commemorative concerts are held periodically, such as the major memorial concert at Tokyo Dome on November 11, 2012, featuring numerous contemporary artists paying tribute by singing her famous songs.

- AI-Powered Performances**:

- In a groundbreaking initiative in September 2019, NHK Special utilized advanced AI technology to recreate Misora's voice and image. Using Yamaha's VOCALOID:AI deep learning technology, a new song, "あれからArekaraJapanese", was created with her synthesized vocals, accompanied by a 4K 3D hologram of her performing on stage. This "AI Hibari Misora" also performed on the 2019 Kōhaku Uta Gassen, showcasing her continued relevance through technological innovation.

- Cultural Influence**:

- Her songs, especially "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", are played annually on Japanese television and radio on her birth date as a mark of respect.

- Her influence is evident in popular culture, with pachinko machines featuring her image and music, and various television dramas and stage plays depicting her life, such as The Hibari Misora Story (1989) and The Hibari Misora Birth Story (2005).

These ongoing commemorations and modern adaptations ensure that Hibari Misora remains a vibrant and cherished part of Japan's cultural landscape, continuing to inspire and entertain new generations.

11. Awards and Honors

Hibari Misora received numerous awards and honors throughout her career, both during her lifetime and posthumously, recognizing her profound contributions to Japanese music and culture.

- Medal of Honor (Japan)**: Awarded for her contributions to music and for improving public welfare.

- People's Honour Award**: Conferred posthumously on July 2, 1989, making her the first woman to receive this prestigious award. It recognized her role in giving the public hope and encouragement after World War II. Her adopted son, Kazuya Katō, and Kinnosuke Yorozuya attended the ceremony.

- Japan Record Award**:

- Vocal Performance Award (1960) for "哀愁波止場Aishū HatobaJapanese"

- Grand Prize (1965) for "柔YawaraJapanese"

- 15th Anniversary Special Award (1973)

- Special Award (1976)

- Special Honor Singer Award (1989) for "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese"

- Blue Ribbon Award**: Popularity Award (1962) for her enduring popularity as a film actress over 13 years.

- Japan Red Cross Gold Medal of Merit** (October 8, 1969)

- Dark Blue Ribbon Medal** (December 17, 1969)

- Japan Music Award**:

- Special Broadcasting Music Award (1971)

- Special Honor Award (1989)

- Morita Tama Pioneer Award** (1977)

- Japan Lyricist Award**: Special Award (1989)

- FNS Music Festival**: Special Award (1989)

- Aomori Apple Medal** (2000)

Her record on NHK's Kōhaku Uta Gassen is particularly notable: she appeared 17 times, serving as the red team's final performer (Ōtori) 13 times, including 10 consecutive years (1963-1972), which remains an all-time record for any artist. In 1970, she also served as the red team's host, becoming the first and only female artist in Kōhaku history to simultaneously hold both the host and Ōtori roles.

12. Discography

Hibari Misora's discography is extensive, encompassing 1,500 recorded songs and 517 original compositions. Her total record sales reached over 117 M copies by 2019, making her one of the best-selling music artists of all time.

12.1. Notable Singles and Sales

Her top-selling singles, with sales figures as of March 2019 (Nippon Columbia data, including re-releases):

- "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese" (1989) - 2.05 M copies

- "柔YawaraJapanese" (1964) - 1.95 M copies

- "悲しい酒Kanashii SakeJapanese" (1966) - 1.55 M copies

- "真赤な太陽Makka no TaiyōJapanese" (1967) - 1.5 M copies

- "リンゴ追分Ringo OiwakeJapanese" (1952) - 1.4 M copies

- "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese" (1987) - 1.25 M copies

- "港町十三番地Minatomachi Jūsanban-chiJapanese" (1957) - 1.2 M copies

- "東京キッドTokyo KidJapanese" (1950) - 1.2 M copies

- "悲しき口笛Kanashiki KuchibueJapanese" (1949) - 1.1 M copies

- "波止場だよ、お父つぁんHatoba dayo, OtochanJapanese" (1956) - 1.1 M copies

12.2. Selected Albums

Hibari Misora released numerous original albums, cover albums, live albums, and best-of compilations throughout her career.

Original Albums:

- Hibari no Madorosu-san (1958)

- Hibari no Uta Nikki (1958)

- Hibari no Hana Moyō (1960)

- Kono Uta to Tomoni (1961)

- Uta wa Waga Inochi ~ Misora Hibari Geinō Seikatsu 20 Shūnen Kinen (1967)

- Omae ni Horeta (1980)

- Fushichō (1988)

- Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni ~ Fushichō Part II (1988)

Cover Albums:

- Hibari Jazz o Utau ~ Nat King Cole o Shinonde (1965)

- Hibari Min'yō o Utau (1966)

- Kokoro no Gunka ~ Misora Hibari Aishū no Gunka o Utau (1972)

- Watashi to Anata no Chiisana Snack (1976)

Live Albums:

- Hibari no Hana Emaki (1958)

- Misora Hibari Recital (1968)

- Hibari in America (1974)

- Geinō Seikatsu 35 Shūnen Kinen Misora Hibari Budokan Live (1981)

- Fushichō Misora Hibari in Tokyo Dome (1988)

- Uta wa Waga Inochi 1989 in Kokura ~ Misora Hibari Last On Stage "Sayonara no Mukō ni" (2005) - Recording of her final performance.

Best Albums and Special Releases:

- Misora Hibari Zenkyokushū (1962) - Her first comprehensive collection.

- Misora Hibari Daizenshū Kyō no Ware ni Asu wa Katsu (1989) - A 35-CD, 517-song compilation released posthumously, selling 63,000 sets.

- Misora Hibari Treasures (2011) - A treasure book with unreleased songs, photos, and replicas.

- Hibari Senya Ichie (2011) - A 56-CD, 2-DVD set containing 1,001 songs, the largest collection by a single artist.

- Misora Hibari & Kawada Haruhisa in America 1950 (2013) - A CD of rediscovered recordings from her 1950 US tour.

- Arekara (2019) - A new song featuring AI-synthesized vocals, released posthumously.

13. Filmography

Hibari Misora starred in 166 films from 1949 to 1971, with most of them being leading roles. Her film career was a significant part of her stardom, contributing to the golden age of Japanese cinema.

- Nodo jimankyō jidai (1949)

- Odoru Ryūgūjō (1949)

- Kanashiki Kuchibue (1949)

- Tokyo Kid (1950)

- Aozora Tenshi (1950)

- Kurama Tengu: Kakubējishi (1951)

- Haha wo Shitaite (1951)

- Ano Oka Koete (1951)

- Yōki-na Wataridori (1952)

- Ringo-en no Shōjo (1952)

- Ushiwakamaru (1952)

- Ojōsan Shachō (1953)

- Izu no Odoriko (1954)

- Yaoya Oshichi Furisode Tsukiyo (1954)

- Janken Musume (1955)

- Takekurabe (1955)

- Romance Musume (1956)

- Ōatari Sanshoku Musume (1957)

- Ōatari Tanukigoten (1958)

- Hibari Torimonochō: Kanzashi Koban (1958)

- Chūshingura: Ōka no Maki, Kikka no Maki (1959)

- Beranmē Geisha (1959)

- Samurai Vagabond (1960)

- Hibari no Mori no Ishimatsu (1960)

- Sen-hime to Hideyori (1962)

- Hibari no Hahakoi Guitar (1962)

- Hibari, Chiemi, Izumi: Sannin Yoreba (1964)

- Noren Ichidai: Jokyo (1966)

- Gion Matsuri (1968)

- Hibari no Subete (1971)

- Onna no Hanamichi (1971)

14. Personal Life and Relationships

Hibari Misora's personal life was marked by deep family bonds, public scrutiny, and significant losses. Her mother, Kimie Katō, was an exceptionally influential figure in her life, serving not only as her devoted parent but also as her primary producer and manager throughout her career. Their closeness was so profound that they were often referred to as "one-egg parents" by the media. Kimie's influence extended to Hibari's romantic life, as she openly expressed her disapproval of Hibari's marriage to actor Akira Kobayashi, later stating that the unhappiest moment of her life was her daughter's marriage to Kobayashi, and the happiest was their divorce.

In 1956, Hibari was briefly engaged to jazz musician Mitsuru Ono, but the engagement was called off due to the condition that she would have to give up her career to marry.

In 1962, Hibari married Akira Kobayashi, a top actor from Nikkatsu. Their marriage, however, was short-lived, ending in divorce in 1964 after just two years. Although Kobayashi desired to formally register their marriage, Kimie consistently refused, citing concerns about property disposition. Consequently, Hibari remained legally single throughout her life. The constant interference from her mother and other associates, coupled with Hibari's reluctance to fully abandon her career, contributed to the marriage's dissolution. Kobayashi later recalled that Hibari tried her best to be a good wife, describing her as "the best as a woman." The term "understanding divorce" became a buzzword after their separate press conferences. Kobayashi expressed deep regret, stating he wished he could cry in front of everyone, as the divorce was not his true intention. Hibari, accompanied by Kazuo Taoka, stated that revealing the reasons would hurt both parties and that she chose the path to her own happiness, emphasizing her inability to abandon her art or her mother.

A year after her marriage, in 1963, her father, Masukichi, passed away at the age of 52 from pulmonary tuberculosis.

In 1973, Hibari faced a major controversy when her younger brother, Tetsuya Katō, was arrested for gang-related activities. Tetsuya, who had debuted as a singer under the stage name Ono Tōru in 1957, became a senior member of the Masuda-gumi, a branch of the Yamaguchi-gumi. He had a history of arrests for gambling, illegal firearm possession, assault, and smuggling. This incident brought to light the Katō family's ties with the Yamaguchi-gumi and its leader, Kazuo Taoka, who was also involved in Hibari's management. As a direct consequence, many public venues refused to host her performances if her brother was involved, leading to widespread media criticism. This led to her exclusion from NHK's prestigious Kōhaku Uta Gassen for the first time in 18 years, effectively a ban. Offended by this, Misora refused to appear on any NHK programs for several years, though she eventually made peace with the broadcaster, appearing as a special guest on the 1979 Kōhaku, which was her final appearance on the program.

In 1978, Hibari adopted her seven-year-old nephew, Kazuya Katō, Tetsuya's son.

The 1980s proved to be an incredibly difficult period for Hibari due to a series of profound personal losses. Her beloved mother, Kimie, passed away in 1981 at the age of 68 from metastatic brain tumor. Her 35th-anniversary recital at the Nippon Budokan that year was held while Kimie was in critical condition. Her father figure, Kazuo Taoka, also died shortly after. In 1982, her close friend and fellow singer/actress, Chiemi Eri, died suddenly at 45. Her two younger brothers, Tetsuya and Takehiko Kayama, both died young at 42 in 1983 and 1986, respectively. To cope with her immense sorrow and loneliness, Hibari, already known for her heavy drinking and smoking, increased her consumption, which began to severely impact her health.

Hibari maintained deep friendships with many prominent figures across entertainment, sports, and politics. She was particularly close to Sadaharu Oh, whom she considered a "brother," and also had strong ties with Masaichi Kaneda. She was also a mentor to comedian Shinji Maki and had a unique relationship with the comedy duo Tunnels, whom she affectionately called "Taka" and "Nori," treating them like younger brothers.

15. Health Struggles and Later Years

The demanding nature of Hibari Misora's career, coupled with her increasing reliance on alcohol and cigarettes to cope with personal tragedies, took a severe toll on her health in the 1980s. In May 1985, during a golf competition celebrating her birthday, she twisted her lower back, experiencing sharp, pulling pains in both inner thighs. She began complaining of unexplained lower back pain, which gradually worsened, though she continued to perform with unwavering passion, showing no signs of discomfort. In 1986, she held her 40th-anniversary recitals in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. However, by February 1987, during her Shikoku tour, the pain in her legs became unbearable.

Despite her deteriorating health, she visited Toba City in Mie Prefecture to see the sea otters at Toba Aquarium, a personal request. She also filmed a karaoke video there. During a retake, she struggled to step over a small rise and needed assistance to walk, completing the shoot with help from her attendant. Footage from this period, showing her walking with difficulty, is still used in karaoke videos for songs like "Ringo Oiwake" and "Makka na Taiyō."

On April 7, just two weeks before her hospitalization, she appeared on Nippon TV's "Columbia Enka Daikōshin," where she was visibly unwell and had to be assisted by Takashi Hosokawa and Chiyoko Shimakura to enter. Despite her condition, she sang "Aisansan" and other songs.

On April 22, 1987, while on tour in Fukuoka, she suddenly collapsed due to extreme ill health and was emergency-hospitalized at Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital. She was diagnosed with severe chronic hepatitis and bilateral idiopathic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Although her actual condition was cirrhosis, this was kept secret from the press to avoid alarming her fans and associates. Her scheduled May performance at the Meiji-za was canceled. On May 29, her 50th birthday, while still hospitalized, she released a voice message to the media and fans, stating, "I am diligently following my doctors' instructions as a model patient. No need to rush, just a little rest."

Amidst the deaths of close friends and Showa-era stars like Kōji Tsuruta (June 16, 1987) and Yujiro Ishihara (July 17, 1987), Hibari was discharged from the hospital on August 3. She greeted her waiting fans with a smile and a flying kiss. At the press conference, she tearfully expressed her unwavering belief in singing again, concluding with a smile, "I will quit alcohol, but I will not quit singing." After two months of home recuperation, she resumed her entertainment activities on October 9 with the recording of her new song "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese."

However, her illness was far from cured. Her liver function had only recovered to about 60% of normal, and the avascular necrosis was deemed difficult to heal. Her health continued to decline, making it difficult for her to even climb stairs alone, requiring a lift to get onto stages.

On April 11, 1988, Hibari held her legendary "Fushichō Concert" (Phoenix Concert) at the newly opened Tokyo Dome. Despite overwhelming pain in her legs and her liver function fluctuating between 20-30%, she performed a total of 39 songs. The audience was unaware of her true condition; backstage, she lay on a bed with an oxygen tank. Celebrities like Mitsuko Mori, Izumi Yukimura, Chiyoko Shimakura, Ruriko Asaka, and Kayoko Kishimoto attended to support her. Ruriko Asaka described her dressing room as resembling a hospital room, recalling Hibari's brave smile and her words, "I'm not okay, but I'll do my best." After her final song, "人生一路Jinsei IchiroJapanese", she slowly walked the 328 ft (100 m) flower path, her face contorted in pain, yet waving to fans. Upon reaching the end, she collapsed into her adopted son Kazuya's arms and was immediately taken away by an ambulance on standby. While the media reported a "complete comeback," it was a performance that cost Hibari her life force.

Her health continued to worsen after the Tokyo Dome concert. She could no longer climb stairs unaided and required lifts for stage entrances. Despite this, she continued to work tirelessly, including recording for her final original album, Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni ~ Fushichō Part II, with young creators like Yasushi Akimoto and Akira Mitake. Her staff initially planned to release "ハハハHahahahaJapanese" as a single, but Hibari passionately insisted on "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", stating, "Please, just this once, indulge my selfishness!" This song, released on January 11, 1989, became her final single.

On December 12, 16, and 17, 1988, she recorded her final one-woman show, "Haru Ichiban! Netshō Misora Hibari," for TBS, which aired on January 4, 1989. Despite her severe pain and breathlessness, she performed mostly seated. At the end, she thanked the staff and guests, saying, "Hibari will continue to sing as much as possible. Because it's the path I chose." She also teared up after receiving words of encouragement from Shigeharu Mori. Her final TV drama appearance was a cameo in "Papa wa News Caster" on January 2, 1989.

By this time, the symptoms of interstitial pneumonitis, her direct cause of death, had already begun. On December 25 and 26, 1988, she held her final Christmas dinner show at the Imperial Hotel, attended by friends like Fukuko Ishii and Sadaharu Oh. Despite her struggles, she performed a vigorous twist, delighting the audience. Ishii later recounted how Hibari, unannounced, appeared at a restaurant where she and Oh were dining after the show and sang a naniwabushi, leaving Ishii deeply moved.

16. Death and National Mourning

On January 8, 1989, as the Japanese era transitioned from Showa to Heisei, Hibari penned a tanka poem: "Heisei no ware shinkai ni nagaretsuki inochi no uta yo odayaka ni..." (In the Heisei era, I flow to a new sea, may my song of life be peaceful...). Just three days later, on January 11, her final single, "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", was released, though her lungs were already severely affected by illness.

She made her last television appearances on Enka no Hanaji and Music Fair on January 15, singing "Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni" and other songs. Her condition continued to deteriorate. A few days before a concert in Fukuoka, she was informed by a doctor that her condition was worsening. Despite strong opposition from those around her, she insisted on performing the concert on February 6 at Fukuoka Sunpalace, where she experienced cyanosis due to worsening cirrhosis. She pushed through, performing the next day, February 7, at Kyushu Koseinenkin Kaikan in Kokura, which became her final stage performance. Due to her extreme weakness, she traveled by helicopter and rested backstage with an oxygen tank, facing the risk of esophageal varices rupture. Her adopted son Kazuya recalled her performing solely on willpower, as doctors warned of imminent collapse. She could not even step over a small rise to the stage alone. She performed 20 songs, mostly seated, concealing her severe idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis.

After her final concert, she was hospitalized for examination at Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital on February 8. After a temporary discharge, she stayed at a friend's home in Fukuoka until late February, returning to Tokyo by helicopter. Her physical strength was completely depleted. Days of home recuperation followed, and despite the cancellation of her nationwide tour, she remained determined to perform at the opening concert of Yokohama Arena, her hometown, on April 17. She adamantly stated, "I want to stand on the Yokohama Arena stage. I will crawl if I have to for this performance!" Her son Kazuya, concerned for her health, urged her to cancel, leading to frequent arguments.

Around this time, a doctor introduced by Fukuko Ishii examined Hibari, noting her blue fingertips and pale face, and strongly recommended hospitalization. On March 9, after a long silence, Hibari tearfully accepted the decision to be re-hospitalized. She was temporarily discharged after further tests and made her final media appearance on March 21, a 10-hour live radio special for Nippon Broadcasting System from her home, where she stated, "Hibari will never retire. I will keep singing and then disappear without anyone noticing." Immediately after the broadcast, her condition worsened, and she was re-hospitalized at Juntendo University Hospital in Tokyo.

Two days later, on March 23, her son Kazuya announced the cancellation of all her concerts, including the Yokohama Arena opening, and a year-long hiatus from all entertainment activities, citing "worsening allergic bronchitis" and "intractable cough" (the actual diagnosis of interstitial pneumonitis was not revealed to the public or to Hibari herself, though she had been informed of it by a doctor in early March).

On May 27, while hospitalized, Hibari released a message to the media along with a photo, stating, "A lark flies from a wheat field... Do not shoot that bird, villagers!" She also released a recorded voice message, expressing her desire to live without regrets. However, her voice was weak and strained compared to her previous hospitalization. This was her final message and recorded voice released to the public.

Two days later, on May 29, Hibari celebrated her 52nd birthday in the hospital. Her sister Setsuko Sato recalled Hibari crying and asking, "Setsuko, can I still live?" to which Setsuko replied, "What are you saying? You're only 52! You have to keep living!" Hibari then said, "You're right, I can't die and leave Kazuya alone. I'll do my best."

Fifteen days after her birthday, on June 13, she experienced severe respiratory distress and was placed on a ventilator. Her last words to the Juntendo Hospital medical team were reportedly, "Thank you. I'll do my best." Kazuya later recounted that a few days before her death, when he encouraged her, she had tears in her eyes, as if she had accepted her fate.

On June 24, 1989, at 0:28 AM, 136 days after her last stage performance and three months after her re-hospitalization, Hibari Misora died at Juntendo University Hospital due to respiratory failure caused by worsening idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis. She was 52 years old. Her death was widely mourned across Japan, and many felt that the Showa period had truly come to an end with her passing. Major television networks canceled their regular programming that evening to broadcast news of her death and air various tributes.

Her wake was held on June 25, followed by her funeral at her residence on June 26, attended by numerous figures from the entertainment, sports, and political worlds. As her hearse left her home, many fans lined the streets to mourn her passing. On July 22, her funeral at Aoyama Funeral Hall in Tokyo attracted a record 42,000 attendees. Kazuya served as chief mourner, and eulogies were delivered by Kinnosuke Yorozuya, Shigeharu Mori, Meiko Kaji, Sadaharu Oh, and Takaaki Ishibashi of Tunnels. Fellow singers like Saburō Kitajima, Izumi Yukimura, Masako Mori, Fumiya Fujii, and Masahiko Kondō sang "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese" in tribute. Her posthumous Buddhist name is Jishōin Misora Nichiwa Seitai-shi. Her grave is located at Hino Public Cemetery in Konan Ward, Yokohama.

17. Legacy and Cultural Impact

Hibari Misora's death did not diminish her immense influence; rather, it solidified her status as an "eternal diva" and cultural icon in Japan. Her legacy continues to resonate deeply through annual television and radio specials dedicated to her music, particularly her swan song, "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese." In a 1997 national poll by NHK, this song was voted the greatest Japanese song of all time by over 10 million people. It has been notably performed as a tribute by international artists such as The Three Tenors, Teresa Teng, Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán, and the Twelve Girls Band.

Posthumous tributes and commemorations abound:

- Memorial Monuments**: In April 1993, a monument featuring Misora's portrait and an inscribed poem was erected near Sugi no Osugi in Ōtoyo, Kōchi. This location holds special significance as a 10-year-old Misora, recovering from a severe bus accident there in 1947, reportedly visited the ancient cedar tree and wished to become Japan's top singer. Her father had wanted her to quit singing after the accident, but she famously declared, "If I can't sing, then I will die." In Iwaki City, Fukushima Prefecture, the setting of her hit song "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese", a song monument was erected on October 2, 1988, followed by a memorial portrait monument on May 26, 1990. The surrounding 1378 ft (420 m) of road was developed as "Hibari Kaidō" (Hibari Road) in 1998, and a bronze statue titled "Eternal Hibari" was erected on May 25, 2002. In October 2024, a bronze statue from the former Kyoto Uzumasa Hibari-za was relocated to Iwaki, further solidifying the site as a place of remembrance.

- Museums and Memorial Halls**: The Hibari Misora Museum opened in Arashiyama, Kyoto, in April 1993, showcasing her personal belongings and career history. After attracting over 5 million visitors, it closed in 2006 for renovation. It reopened as the Hibari Misora Theater in April 2008, and later, in October 2013, a new "Kyoto Uzumasa Hibari-za" opened within the Toei Uzumasa Eigamura, displaying approximately 500 items, including stage costumes and restored film posters. In May 2014, the "Tokyo Meguro Hibari Memorial Hall" opened, converting a part of her former residence in Meguro, Tokyo, into a public museum.

- Posthumous Releases and Events**:

- Her unreleased song "流れ人NagarebitoJapanese", recorded for a 1980 stage play, was released as her first posthumous single in 1999. In 2016, another unreleased recording, "さくらの唄Sakura no UtaJapanese", was released.

- Commemorative concerts are held periodically, such as the major memorial concert at Tokyo Dome on November 11, 2012, featuring numerous contemporary artists paying tribute by singing her famous songs.

- AI-Powered Performances**:

- In a groundbreaking initiative in September 2019, NHK Special utilized advanced AI technology to recreate Misora's voice and image. Using Yamaha's VOCALOID:AI deep learning technology, a new song, "あれからArekaraJapanese", was created with her synthesized vocals, accompanied by a 4K 3D hologram of her performing on stage. This "AI Hibari Misora" also performed on the 2019 Kōhaku Uta Gassen, showcasing her continued relevance through technological innovation.

- Cultural Influence**:

- Her songs, especially "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", are played annually on Japanese television and radio on her birth date as a mark of respect.

- Her influence is evident in popular culture, with pachinko machines featuring her image and music, and various television dramas and stage plays depicting her life, such as The Hibari Misora Story (1989) and The Hibari Misora Birth Story (2005).

These ongoing commemorations and modern adaptations ensure that Hibari Misora remains a vibrant and cherished part of Japan's cultural landscape, continuing to inspire and entertain new generations.

18. Awards and Honors

Hibari Misora received numerous awards and honors throughout her career, both during her lifetime and posthumously, recognizing her profound contributions to Japanese music and culture.

- Medal of Honor (Japan)**: Awarded for her contributions to music and for improving public welfare.

- People's Honour Award**: Conferred posthumously on July 2, 1989, making her the first woman to receive this prestigious award. It recognized her role in giving the public hope and encouragement after World War II. Her adopted son, Kazuya Katō, and Kinnosuke Yorozuya attended the ceremony.

- Japan Record Award**:

- Vocal Performance Award (1960) for "哀愁波止場Aishū HatobaJapanese"

- Grand Prize (1965) for "柔YawaraJapanese"

- 15th Anniversary Special Award (1973)

- Special Award (1976)

- Special Honor Singer Award (1989) for "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese"

- Blue Ribbon Award**: Popularity Award (1962) for her enduring popularity as a film actress over 13 years.

- Japan Red Cross Gold Medal of Merit** (October 8, 1969)

- Dark Blue Ribbon Medal** (December 17, 1969)

- Japan Music Award**:

- Special Broadcasting Music Award (1971)

- Special Honor Award (1989)

- Morita Tama Pioneer Award** (1977)

- Japan Lyricist Award**: Special Award (1989)

- FNS Music Festival**: Special Award (1989)

- Aomori Apple Medal** (2000)

Her record on NHK's Kōhaku Uta Gassen is particularly notable: she appeared 17 times, serving as the red team's final performer (Ōtori) 13 times, including 10 consecutive years (1963-1972), which remains an all-time record for any artist. In 1970, she also served as the red team's host, becoming the first and only female artist in Kōhaku history to simultaneously hold both the host and Ōtori roles.

19. Discography

Hibari Misora's discography is extensive, encompassing 1,500 recorded songs and 517 original compositions. Her total record sales reached over 117 M copies by 2019, making her one of the best-selling music artists of all time.

19.1. Notable Singles and Sales

Her top-selling singles, with sales figures as of March 2019 (Nippon Columbia data, including re-releases):

- "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese" (1989) - 2.05 M copies

- "柔YawaraJapanese" (1964) - 1.95 M copies

- "悲しい酒Kanashii SakeJapanese" (1966) - 1.55 M copies

- "真赤な太陽Makka na TaiyōJapanese" (1967) - 1.5 M copies

- "リンゴ追分Ringo OiwakeJapanese" (1952) - 1.4 M copies

- "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese" (1987) - 1.25 M copies

- "港町十三番地Minatomachi Jūsanban-chiJapanese" (1957) - 1.2 M copies

- "東京キッドTokyo KidJapanese" (1950) - 1.2 M copies

- "悲しき口笛Kanashiki KuchibueJapanese" (1949) - 1.1 M copies

- "波止場だよ、お父つぁんHatoba dayo, OtochanJapanese" (1956) - 1.1 M copies

19.2. Selected Albums

Hibari Misora released numerous original albums, cover albums, live albums, and best-of compilations throughout her career.

Original Albums:

- Hibari no Madorosu-san (1958)

- Hibari no Uta Nikki (1958)

- Hibari no Hana Moyō (1960)

- Kono Uta to Tomoni (1961)

- Uta wa Waga Inochi ~ Misora Hibari Geinō Seikatsu 20 Shūnen Kinen (1967)

- Omae ni Horeta (1980)

- Fushichō (1988)

- Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni ~ Fushichō Part II (1988)

Cover Albums:

- Hibari Jazz o Utau ~ Nat King Cole o Shinonde (1965)

- Hibari Min'yō o Utau (1966)

- Kokoro no Gunka ~ Misora Hibari Aishū no Gunka o Utau (1972)

- Watashi to Anata no Chiisana Snack (1976)

Live Albums:

- Hibari no Hana Emaki (1958)

- Misora Hibari Recital (1968)

- Hibari in America (1974)

- Geinō Seikatsu 35 Shūnen Kinen Misora Hibari Budokan Live (1981)

- Fushichō Misora Hibari in Tokyo Dome (1988)

- Uta wa Waga Inochi 1989 in Kokura ~ Misora Hibari Last On Stage "Sayonara no Mukō ni" (2005) - Recording of her final performance.

Best Albums and Special Releases:

- Misora Hibari Zenkyokushū (1962) - Her first comprehensive collection.

- Misora Hibari Daizenshū Kyō no Ware ni Asu wa Katsu (1989) - A 35-CD, 517-song compilation released posthumously, selling 63,000 sets.

- Misora Hibari Treasures (2011) - A treasure book with unreleased songs, photos, and replicas.

- Hibari Senya Ichie (2011) - A 56-CD, 2-DVD set containing 1,001 songs, the largest collection by a single artist.

- Misora Hibari & Kawada Haruhisa in America 1950 (2013) - A CD of rediscovered recordings from her 1950 US tour.

- Arekara (2019) - A new song featuring AI-synthesized vocals, released posthumously.

20. Filmography

Hibari Misora starred in 166 films from 1949 to 1971, with most of them being leading roles. Her film career was a significant part of her stardom, contributing to the golden age of Japanese cinema.

- Nodo jimankyō jidai (1949)

- Odoru Ryūgūjō (1949)

- Kanashiki Kuchibue (1949)

- Tokyo Kid (1950)

- Aozora Tenshi (1950)

- Kurama Tengu: Kakubējishi (1951)

- Haha wo Shitaite (1951)

- Ano Oka Koete (1951)

- Yōki-na Wataridori (1952)

- Ringo-en no Shōjo (1952)

- Ushiwakamaru (1952)

- Ojōsan Shachō (1953)

- Izu no Odoriko (1954)

- Yaoya Oshichi Furisode Tsukiyo (1954)

- Janken Musume (1955)

- Takekurabe (1955)

- Romance Musume (1956)

- Ōatari Sanshoku Musume (1957)

- Ōatari Tanukigoten (1958)

- Hibari Torimonochō: Kanzashi Koban (1958)

- Chūshingura: Ōka no Maki, Kikka no Maki (1959)

- Beranmē Geisha (1959)

- Samurai Vagabond (1960)

- Hibari no Mori no Ishimatsu (1960)

- Sen-hime to Hideyori (1962)

- Hibari no Hahakoi Guitar (1962)

- Hibari, Chiemi, Izumi: Sannin Yoreba (1964)

- Noren Ichidai: Jokyo (1966)

- Gion Matsuri (1968)

- Hibari no Subete (1971)

- Onna no Hanamichi (1971)

21. Personal Life and Relationships

Hibari Misora's personal life was marked by deep family bonds, public scrutiny, and significant losses. Her mother, Kimie Katō, was an exceptionally influential figure in her life, serving not only as her devoted parent but also as her primary producer and manager throughout her career. Their closeness was so profound that they were often referred to as "one-egg parents" by the media. Kimie's influence extended to Hibari's romantic life, as she openly expressed her disapproval of Hibari's marriage to actor Akira Kobayashi, later stating that the unhappiest moment of her life was her daughter's marriage to Kobayashi, and the happiest was their divorce.

In 1956, Hibari was briefly engaged to jazz musician Mitsuru Ono, but the engagement was called off due to the condition that she would have to give up her career to marry.

In 1962, Hibari married Akira Kobayashi, a top actor from Nikkatsu. Their marriage, however, was short-lived, ending in divorce in 1964 after just two years. Although Kobayashi desired to formally register their marriage, Kimie consistently refused, citing concerns about property disposition. Consequently, Hibari remained legally single throughout her life. The constant interference from her mother and other associates, coupled with Hibari's reluctance to fully abandon her career, contributed to the marriage's dissolution. Kobayashi later recalled that Hibari tried her best to be a good wife, describing her as "the best as a woman." The term "understanding divorce" became a buzzword after their separate press conferences. Kobayashi expressed deep regret, stating he wished he could cry in front of everyone, as the divorce was not his true intention. Hibari, accompanied by Kazuo Taoka, stated that revealing the reasons would hurt both parties and that she chose the path to her own happiness, emphasizing her inability to abandon her art or her mother.

A year after her marriage, in 1963, her father, Masukichi, passed away at the age of 52 from pulmonary tuberculosis.

In 1973, Hibari faced a major controversy when her younger brother, Tetsuya Katō, was arrested for gang-related activities. Tetsuya, who had debuted as a singer under the stage name Ono Tōru in 1957, became a senior member of the Masuda-gumi, a branch of the Yamaguchi-gumi. He had a history of arrests for gambling, illegal firearm possession, assault, and smuggling. This incident brought to light the Katō family's ties with the Yamaguchi-gumi and its leader, Kazuo Taoka, who was also involved in Hibari's management. As a direct consequence, many public venues refused to host her performances if her brother was involved, leading to widespread media criticism. This led to her exclusion from NHK's prestigious Kōhaku Uta Gassen for the first time in 18 years, effectively a ban. Offended by this, Misora refused to appear on any NHK programs for several years, though she eventually made peace with the broadcaster, appearing as a special guest on the 1979 Kōhaku, which was her final appearance on the program.

In 1978, Hibari adopted her seven-year-old nephew, Kazuya Katō, Tetsuya's son.

The 1980s proved to be an incredibly difficult period for Hibari due to a series of profound personal losses. Her beloved mother, Kimie, passed away in 1981 at the age of 68 from metastatic brain tumor. Her 35th-anniversary recital at the Nippon Budokan that year was held while Kimie was in critical condition. Her father figure, Kazuo Taoka, also died shortly after. In 1982, her close friend and fellow singer/actress, Chiemi Eri, died suddenly at 45. Her two younger brothers, Tetsuya and Takehiko Kayama, both died young at 42 in 1983 and 1986, respectively. To cope with her immense sorrow and loneliness, Hibari, already known for her heavy drinking and smoking, increased her consumption, which began to severely impact her health.

Hibari maintained deep friendships with many prominent figures across entertainment, sports, and politics. She was particularly close to Sadaharu Oh, whom she considered a "brother," and also had strong ties with Masaichi Kaneda. She was also a mentor to comedian Shinji Maki and had a unique relationship with the comedy duo Tunnels, whom she affectionately called "Taka" and "Nori," treating them like younger brothers.

22. Health Struggles and Later Years

The demanding nature of Hibari Misora's career, coupled with her increasing reliance on alcohol and cigarettes to cope with personal tragedies, took a severe toll on her health in the 1980s. In May 1985, during a golf competition celebrating her birthday, she twisted her lower back, experiencing sharp, pulling pains in both inner thighs. She began complaining of unexplained lower back pain, which gradually worsened, though she continued to perform with unwavering passion, showing no signs of discomfort. In 1986, she held her 40th-anniversary recitals in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. However, by February 1987, during her Shikoku tour, the pain in her legs became unbearable.

Despite her deteriorating health, she visited Toba City in Mie Prefecture to see the sea otters at Toba Aquarium, a personal request. She also filmed a karaoke video there. During a retake, she struggled to step over a small rise and needed assistance to walk, completing the shoot with help from her attendant. Footage from this period, showing her walking with difficulty, is still used in karaoke videos for songs like "Ringo Oiwake" and "Makka na Taiyō."

On April 7, just two weeks before her hospitalization, she appeared on Nippon TV's "Columbia Enka Daikōshin," where she was visibly unwell and had to be assisted by Takashi Hosokawa and Chiyoko Shimakura to enter. Despite her condition, she sang "Aisansan" and other songs.

On April 22, 1987, while on tour in Fukuoka, she suddenly collapsed due to extreme ill health and was emergency-hospitalized at Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital. She was diagnosed with severe chronic hepatitis and bilateral idiopathic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Although her actual condition was cirrhosis, this was kept secret from the press to avoid alarming her fans and associates. Her scheduled May performance at the Meiji-za was canceled. On May 29, her 50th birthday, while still hospitalized, she released a voice message to the media and fans, stating, "I am diligently following my doctors' instructions as a model patient. No need to rush, just a little rest."

Amidst the deaths of close friends and Showa-era stars like Kōji Tsuruta (June 16, 1987) and Yujiro Ishihara (July 17, 1987), Hibari was discharged from the hospital on August 3. She greeted her waiting fans with a smile and a flying kiss. At the press conference, she tearfully expressed her unwavering belief in singing again, concluding with a smile, "I will quit alcohol, but I will not quit singing." After two months of home recuperation, she resumed her entertainment activities on October 9 with the recording of her new song "みだれ髪MidaregamiJapanese."

However, her illness was far from cured. Her liver function had only recovered to about 60% of normal, and the avascular necrosis was deemed difficult to heal. Her health continued to decline, making it difficult for her to even climb stairs alone, requiring a lift to get onto stages.

On April 11, 1988, Hibari held her legendary "Fushichō Concert" (Phoenix Concert) at the newly opened Tokyo Dome. Despite overwhelming pain in her legs and her liver function fluctuating between 20-30%, she performed a total of 39 songs. The audience was unaware of her true condition; backstage, she lay on a bed with an oxygen tank. Celebrities like Mitsuko Mori, Izumi Yukimura, Chiyoko Shimakura, Ruriko Asaka, and Kayoko Kishimoto attended to support her. Ruriko Asaka described her dressing room as resembling a hospital room, recalling Hibari's brave smile and her words, "I'm not okay, but I'll do my best." After her final song, "人生一路Jinsei IchiroJapanese", she slowly walked the 328 ft (100 m) flower path, her face contorted in pain, yet waving to fans. Upon reaching the end, she collapsed into her adopted son Kazuya's arms and was immediately taken away by an ambulance on standby. While the media reported a "complete comeback," it was a performance that cost Hibari her life force.

Her health continued to worsen after the Tokyo Dome concert. She could no longer climb stairs unaided and required lifts for stage entrances. Despite this, she continued to work tirelessly, including recording for her final original album, Kawa no Nagare no Yō ni ~ Fushichō Part II, with young creators like Yasushi Akimoto and Akira Mitake. Her staff initially planned to release "ハハハHahahahaJapanese" as a single, but Hibari passionately insisted on "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", stating, "Please, just this once, indulge my selfishness!" This song, released on January 11, 1989, became her final single.

On December 12, 16, and 17, 1988, she recorded her final one-woman show, "Haru Ichiban! Netshō Misora Hibari," for TBS, which aired on January 4, 1989. Despite her severe pain and breathlessness, she performed mostly seated. At the end, she thanked the staff and guests, saying, "Hibari will continue to sing as much as possible. Because it's the path I chose." She also teared up after receiving words of encouragement from Shigeharu Mori. Her final TV drama appearance was a cameo in "Papa wa News Caster" on January 2, 1989.

By this time, the symptoms of interstitial pneumonitis, her direct cause of death, had already begun. On December 25 and 26, 1988, she held her final Christmas dinner show at the Imperial Hotel, attended by friends like Fukuko Ishii and Sadaharu Oh. Despite her struggles, she performed a vigorous twist, delighting the audience. Ishii later recounted how Hibari, unannounced, appeared at a restaurant where she and Oh were dining after the show and sang a naniwabushi, leaving Ishii deeply moved.

23. Death and National Mourning

On January 8, 1989, as the Japanese era transitioned from Showa to Heisei, Hibari penned a tanka poem: "Heisei no ware shinkai ni nagaretsuki inochi no uta yo odayaka ni..." (In the Heisei era, I flow to a new sea, may my song of life be peaceful...). Just three days later, on January 11, her final single, "川の流れのようにKawa no Nagare no Yō niJapanese", was released, though her lungs were already severely affected by illness.