1. Overview

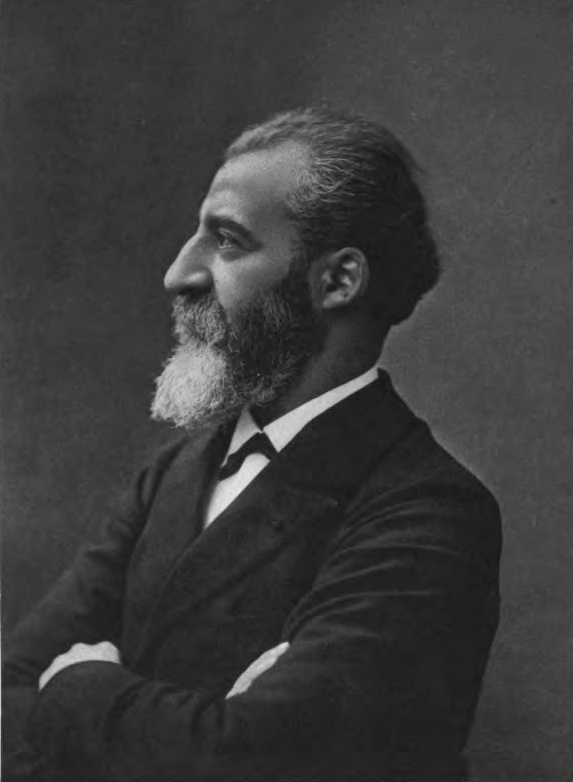

Ferdinand Frédéric Henri Moissan (Ferdinand Frédéric Henri Moissanfɛʁdinɑ fʁedeʁik ɑʁi mwasɑFrench; 28 September 1852 - 20 February 1907) was a prominent French chemist and pharmacist. He is best known for his groundbreaking work in isolating the highly reactive element fluorine from its compounds, an achievement for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1906. Moissan also gained recognition for his invention and development of the electric arc furnace, a revolutionary tool that enabled the synthesis of various new chemical compounds at extremely high temperatures. Beyond these major contributions, his research included attempts to synthesize diamonds and the discovery of the natural mineral moissanite. He was an original member of the International Atomic Weights Committee.

2. Biography

Henri Moissan's life journey led him from humble beginnings and a challenging early education to the pinnacle of scientific achievement, marked by his persistent dedication to chemistry.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Moissan was born in Paris, France, on September 28, 1852. His father, Francis Ferdinand Moissan, was a minor officer for the Eastern Railway Company, and his mother, Joséphine Améraldine (née Mitel), was a seamstress of Jewish descent. In 1864, his family relocated to Meaux, where he attended the local school. During his time there, Moissan began an apprenticeship as a clockmaker. However, in 1870, the Franco-Prussian War compelled Moissan and his family to move back to Paris. Despite his desire to pursue higher education, Moissan was initially unable to obtain the necessary grade universitaire for university admission. Following a year of service in the army, he eventually enrolled at the École Supérieure de Pharmacie de Paris.

2.2. Academic Career

Moissan's formal scientific career commenced in 1871 when he became a trainee in pharmacy. A pivotal moment in 1872 saw him working for a chemist in Paris, where he successfully intervened in a case of arsenic poisoning, an experience that solidified his resolve to study chemistry. He began his chemical studies first in the laboratory of Edmond Frémy at the Musée d'Histoire Naturelle, and later continued his work under Pierre Paul Dehérain at the École Pratique des Haute Études. Dehérain played a crucial role in persuading Moissan to commit to an academic career.

After an earlier unsuccessful attempt, Moissan finally passed the baccalauréat in 1874, a qualification essential for university study. He further advanced his credentials by becoming a first-class pharmacist at the École Supérieure de Pharmacie in 1879, and subsequently earned his doctoral degree from the same institution in 1880.

His academic ascent within the School of Pharmacy was swift. By 1886, he was appointed Assistant Lecturer, then Senior Demonstrator, and eventually Professor of Toxicology. In 1899, he was awarded the Chair of Inorganic Chemistry. The following year, in 1900, he succeeded Louis Joseph Troost as Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the Sorbonne. During his time in Paris, he cultivated friendships with notable contemporaries, including the chemist Alexandre Léon Étard and the botanist Vasque.

3. Scientific Research and Achievements

Henri Moissan's scientific endeavors were marked by his perseverance in tackling difficult chemical problems and his innovative approach to high-temperature synthesis, leading to several significant breakthroughs.

3.1. Isolation of Fluorine

The isolation of fluorine was one of the most challenging problems in 19th-century chemistry. Despite its existence being known since Carl Wilhelm Scheele's work in 1771, all previous attempts to isolate it had failed, and some experimenters even died due to fluorine's extreme reactivity and toxicity. Moissan himself sustained an injury to one eye during these perilous experiments.

During the 1880s, Moissan dedicated his efforts to fluorine chemistry and the daunting task of producing pure fluorine. Lacking his own laboratory, he often borrowed space from others, including Charles Friedel. It was in Friedel's lab that he had access to a powerful battery comprising 90 Bunsen cells, which allowed him to experiment with the electrolysis of molten arsenic trichloride, though the gas produced was reabsorbed by the trichloride.

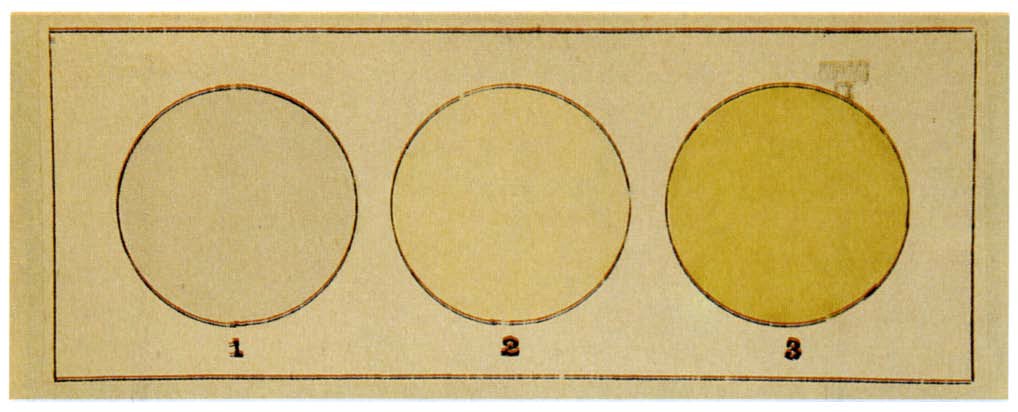

Moissan finally achieved success on June 26, 1886. He managed to isolate fluorine by the electrolysis of a solution of potassium hydrogen difluoride (KHF₂) in liquid hydrogen fluoride (HF). This specific mixture was crucial because hydrogen fluoride itself is a nonconductor. He meticulously designed an apparatus with platinum-iridium electrodes housed in a platinum holder, and the entire setup was cooled to -58 °F (-50 °C). This allowed for the complete separation of hydrogen produced at the negative electrode from fluorine generated at the positive one.

The French Academy of Science dispatched three representatives-Marcellin Berthelot, Henri Debray, and Edmond Frémy-to verify his results. Initially, Moissan was unable to reproduce the outcome, as the hydrogen fluoride he used for the demonstration lacked the trace amounts of potassium fluoride that had been present in his successful prior experiments. After identifying and resolving this critical issue, he demonstrated the production of fluorine multiple times, which earned him a prize of 10.00 K FRF. For this monumental achievement, he was ultimately awarded the 1906 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His method remains the standard for commercial fluorine production today. Following this breakthrough, Moissan's research expanded to characterizing fluorine's chemistry, leading to the discovery of numerous fluorine compounds, including sulfur hexafluoride in 1901, which he discovered alongside Paul Lebeau.

3.2. Development and Application of the Electric Arc Furnace

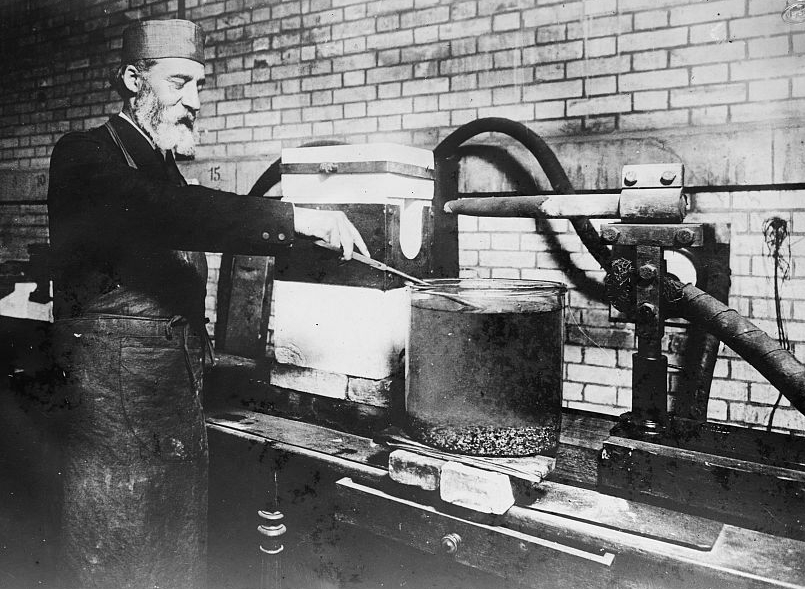

Moissan's ingenuity extended beyond fluorine chemistry to the realm of high-temperature synthesis. He significantly contributed to the development of the electric arc furnace, a device that allowed him to achieve unprecedented temperatures, reaching up to 38.3 K °F (3.50 K °C) with a power supply of 220 amperes and 80 volts by 1900. He published his studies on this invention in his 1897 book, Le Four électrique (The Electric Furnace).

This groundbreaking furnace opened new avenues for developing and preparing compounds that were previously thought to be intractable or impossible to synthesize. For example, in 1892, Moissan and Thomas Willson developed a commercial method for producing calcium carbide, which had been first generated by Friedrich Wöhler. This achievement was particularly significant as it paved the way for the extensive development of acetylene chemistry. Moissan extensively used his furnace to synthesize various borides and carbides of numerous elements, further expanding the field of inorganic chemistry.

3.3. Other Discoveries and Research

Beyond his work on fluorine and the electric arc furnace, Moissan pursued other notable research areas. One such endeavor involved his attempts to create synthetic diamonds. Using his electric arc furnace, he melted iron and carbon together and then rapidly cooled the mixture, hoping the contraction pressure of the metal would crystallize the carbon into diamonds. He announced the successful synthesis of diamonds in 1893. However, after Moissan's death, there was speculation, reportedly from an assistant's confession, that natural diamonds had been secretly introduced into the samples to please him.

Another significant discovery came in 1893, when Moissan began studying fragments of a meteorite recovered from Meteor Crater near Diablo Canyon in Arizona. Within these fragments, he found minute quantities of a new mineral. After extensive research, Moissan concluded that this mineral was composed of silicon carbide (SiC). In 1905, this mineral was officially named moissanite in his honor.

Earlier in his career, in 1874, Moissan published his first scientific paper with Dehérain, focusing on carbon dioxide and oxygen metabolism in plants. He later shifted his focus to inorganic chemistry, and his subsequent research on pyrophoric iron gained considerable recognition from prominent French inorganic chemists of the time, Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville and Jules Henri Debray. His doctoral degree in 1880 was based on his research into cyanogen and its reactions to form cyanides.

4. Personal Life

Henri Moissan married Léonie Lugan in 1882. The couple had one son, named Louis Ferdinand Henri, who was born in 1885. Beyond his scientific pursuits, Moissan also had a passion for collecting art.

5. Awards and Honors

Henri Moissan received numerous accolades throughout his distinguished career, authoring more than three hundred scientific publications. His most significant recognition came in 1906 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking isolation of fluorine and for his innovative development of the electric arc furnace. Notably, he reportedly won the Nobel Prize by a single vote against the renowned Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, and was the second person of Jewish descent to receive a Nobel Prize.

Other major honors and awards bestowed upon him include:

- The Prix Lucaze

- The Davy Medal in 1896

- The Elliott Cresson Medal in 1898

- The Hofmann Medal in 1903

He was also elected as a fellow of the Royal Society and The Chemical Society of London. Furthermore, he served on the International Atomic Weights Committee, having been elected in 1903 and serving until his death. In recognition of his contributions to France, he was made a commandeur in the Légion d'honneur.

6. Death

Henri Moissan died suddenly in Paris on February 20, 1907, at the age of 54. His death occurred shortly after his return from Stockholm, where he had received the Nobel Prize. While his death was officially attributed to an acute case of appendicitis, there has been speculation that his repeated exposure to highly toxic substances, particularly fluorine and carbon monoxide, during his extensive research career, may have contributed to his premature passing.

7. Legacy and Impact

Henri Moissan left an enduring legacy in the field of chemistry. His successful isolation of fluorine marked a monumental achievement, solving a long-standing chemical challenge and making the element available for further study and application. This breakthrough inaugurated the field of fluorine chemistry, which has since become vital in various industrial and scientific domains, including the synthesis of compounds like sulfur hexafluoride and the ongoing use of Moissan's electrolytic method for commercial fluorine production.

The invention and development of the electric arc furnace revolutionized high-temperature chemistry. This innovation allowed for the synthesis of many previously unattainable compounds, such as various carbides and borides, and played a crucial role in the development of acetylene chemistry through the commercial production of calcium carbide. While his attempts to synthesize diamonds were met with some controversy, his pioneering work with the electric arc furnace firmly established its potential for high-temperature synthesis. Furthermore, his discovery of moissanite in meteorites added a new dimension to mineralogy.

Moissan's dedication to rigorous experimentation, his perseverance in the face of scientific challenges and personal risks, and his innovative spirit cemented his place as one of the most influential chemists of his time. His scientific contributions are comprehensively documented in his numerous publications, including his significant works Le Fluor et ses composés (1900) and Le Four électrique (1897).

8. External links

- [https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1906/moissan/biographical/ Biography of Henri Moissan] on Nobelprize.org

- [https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henri-Moissan Biography of Henri Moissan] on Britannica

- [https://www.scs.uiuc.edu/~mainzv/Web_Genealogy/Info/moissanffh.pdf Scientific genealogy]

- [http://europeana.eu/portal/search.html?query=who%3A+henri+moissan Books and letters by Henri Moissan] in Europeana