1. Biography

Hajime Kawakami's life was a journey of intellectual development, social critique, and political engagement, profoundly shaping his contributions to economics and Japanese society.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Hajime Kawakami was born on October 20, 1879, in Iwakuni, Kuga District, Yamaguchi Prefecture (present-day Iwakuni). He was born into a former samurai family of the Iwakuni Domain and was reportedly doted upon by his grandmother, which led to him being somewhat spoiled in his youth. After graduating from Yamaguchi Ordinary Middle School, he went on to graduate from the Law Department of Yamaguchi High School in 1898. He then enrolled in the Faculty of Law, Political Science, at Tokyo Imperial University. During his time in Tokyo, Kawakami was deeply shocked by the stark wealth disparities he witnessed, a stark contrast to his hometown. He was significantly influenced by the Christian thinker Uchimura Kanzō. In November 1901, he was profoundly moved by a speech on the Ashio Copper Mine pollution incident given by Naoe Kinoshita and Shōzō Tanaka at the Tokyo Hongo Central Hall. In an act of spontaneous generosity, he donated his coat, haori, and scarf on the spot, an act that was reported by the Tokyo Mainichi Shimbun as an "especially devoted university student." He graduated from Tokyo Imperial University in 1902. Following his graduation, he began contributing to the State Studies magazine, where he started to formulate his ambition to contribute to human happiness through the study of economics.

1.2. Journalism and Early Career

In 1903, Kawakami began his professional career as a lecturer at the Practical School of the Faculty of Agriculture at Tokyo Imperial University. He concurrently held lecturing positions at various institutions, including Senshu School, Taiwan Association Technical School, and Gakushuin University. During this period, he also wrote extensively on economic topics for the Yomiuri Shimbun. In December 1905, he resigned from his teaching positions and briefly joined the "Mugaa-en" (無我苑Mugaa-enJapanese, "Garden of Selflessness"), a community advocating for selflessness led by Shōshin Itō. However, he left Mugaa-en in February 1906 and subsequently joined the Yomiuri Shimbun as a full-time staff writer.

1.3. Professorship at Kyoto Imperial University

In 1908, Hajime Kawakami was invited by Kinji Tajima to become a lecturer at Kyoto Imperial University (now Kyoto University), marking a significant shift to a research-focused academic life. In 1912, he authored Studies in Economics (経済学研究Keizaigaku KenkyūJapanese), a collection of essays that summarized his research up to that point. From 1913 to 1915, he embarked on a two-year study trip to Europe, which greatly broadened his intellectual horizons. Upon his return, he was appointed a professor at Kyoto Imperial University. In 1914, he was awarded a Doctor of Law degree. In September 1920, he became the Dean of the Faculty of Economics at Kyoto Imperial University, a testament to his growing academic influence.

1.4. Turn to Marxism and "Poverty Tale"

Kawakami's intellectual journey increasingly led him towards Marxist economics. His influential work, Poverty Tale (貧乏物語Binbō MonogatariJapanese), was serialized in the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun from September 11 to December 26, 1916, and published as a book in March 1917. The book became a best-seller amidst the intellectual ferment of the Taishō Democracy, addressing the pressing issue of poverty from an economic perspective. Initially, Kawakami argued that poverty could be eliminated if the wealthy abandoned luxury, asserting that the creation of working poor resulted from the rich's extravagance and society's failure to produce necessities for the poor. He believed that if society as a whole embraced frugality, poverty would be resolved. However, this view was sharply criticized as unrealistic by fellow economist Tokuzo Fukuda and socialist Toshihiko Sakai.

On January 20, 1919, Kawakami launched his personal magazine, Studies of Social Problems (社会問題研究Shakai Mondai KenkyūJapanese), which continued until October 1930. This publication served as a platform for him to disseminate Marxist economic theories to students and laborers. In 1921, a paper he authored titled "Fragments" (断片DanpenJapanese) led to the banning of the magazine Kaizō, and it is believed to have influenced Daisuke Namba, who later carried out the Toranomon Incident. In 1924, Minzō Kushida of the Rōnō-ha (Labor-Farmer Faction) severely criticized Kawakami's interpretation of Marxism. Kawakami acknowledged the validity of the criticism and was spurred to delve deeper into the essence of Marxism. He proceeded to translate numerous Marxist texts, including Das Kapital, and his lectures exerted significant influence on his students. From February 1927 to December 1928, he published "Self-Purification Regarding Historical Materialism" in Studies of Social Problems. His works from this period, particularly Outline of Economics (経済学大綱Keizaigaku TaikōJapanese) and Introduction to Das Kapital (資本論入門Shihonron NyūmonJapanese), played a decisive role in the development of theoretical economics in Japan during the 1920s and 1930s.

1.5. Social and Political Activism

Kawakami's increasing engagement with Marxist thought led to his resignation from Kyoto Imperial University on April 18, 1928. The university pressured him to resign due to what it deemed "inappropriate short texts" in an advertisement booklet for his "Marxist Economics course," "inappropriate sections" in an election speech he delivered in Kagawa Prefecture, and the emergence of individuals who "disturbed public order" from his social science research group. Students at the Faculty of Economics organized a protest meeting with about 400 participants against the university authorities' decision. However, the Ministry of Education had already issued a nationwide policy to dismiss "left-leaning professors," making it impossible to reverse the decision. Ironically, on the same day of his dismissal, Kawakami was granted a special salary increase, raising his salary by 700 JPY (from fourth-grade to second-grade pay).

Following his resignation, Kawakami participated in the formation of the Labor-Farmer Party under Ikuo Oyama. In 1930, he moved from Kyoto to Tokyo. However, he soon criticized the Labor-Farmer Party and broke ties with Oyama. During this period, he serialized Second Poverty Tale (第二貧乏物語Daini Binbō MonogatariJapanese) in the magazine Kaizō, which became widely read as an introductory text to Marxism. During the Shōwa Depression, Kawakami controversially argued that deflation was not an issue that needed to be resolved and that even overcoming deflation would not resolve the fundamental limitations of the capitalist economy.

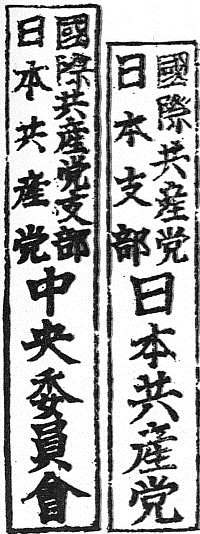

1.6. Involvement with the Japanese Communist Party

After resigning from Kyoto Imperial University and immersing himself in the translation of Das Kapital, Hajime Kawakami began providing financial support to the underground Japanese Communist Party (JCP) in the early Shōwa period. Initially, his contributions were small donations to grassroots activists. However, by the summer of 1931, through Shunichi Sugino, a civil law scholar at Nihon University, Kawakami established direct contact with the Party Central Committee and began channeling funds directly to them. While his initial contributions were in the hundreds of yen per month (equivalent to approximately 200.00 K JPY in today's value), he was frequently asked for larger, temporary donations in the thousands of yen.

On September 9, 1932, Kawakami himself formally joined the Japanese Communist Party. At the time of his entry, he provided a substantial sum of 15.00 K JPY to the party. The same month, he went underground to participate in clandestine activities. His work within the party included assisting with the editing of the party's official newspaper, Akahata, and participating in the creation and writing of political pamphlets. One of his most notable contributions during this period was the swift acquisition and translation of the Comintern's 1932 Theses, officially titled "Theses on the Situation in Japan and the Tasks of the Japanese Communist Party." He published this translation in a special issue of Akahata on July 10, under the pseudonym Hirofuji Honda. Kawakami continued his underground activities until January 12, 1933, when a unit from the Metropolitan Police Department's Special Higher Police raided a painter's house in Nakano Ward, where he was hiding, and arrested him. He was indicted on January 26, 1933, for violating the Public Security Preservation Law. On July 6, 1933, from a solitary cell for unconvicted prisoners at Ichigaya Prison, he issued a statement titled "Prison Soliloquy" (獄中独語Gokuchū DokugoJapanese) to various newspapers, declaring his complete withdrawal from all practical political activities.

1.7. Imprisonment and "Tenko" (Ideological Conversion)

On August 1, 1933, Hajime Kawakami was again arrested as part of the "New Communist Party Incident," which was the fourth major government crackdown on the JCP. He was apprehended along with other prominent figures such as Kinosuke Otsuka, a professor at Tokyo University of Commerce, and Yasoji Kazahaya, a former professor at Kyushu Imperial University. Kawakami was sentenced to five years in prison for violating the Public Security Preservation Law and was initially incarcerated at Toyotama Prison, later transferred to Ichigaya Prison. As a result of his conviction, he was stripped of his court rank (Junior Fourth Rank, Shōshii) and his decorations, including the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 3rd Class, and the Taishō Enthronement Commemorative Medal.

During his imprisonment, Kawakami issued a statement acknowledging the defeat of his Communist Party activities and announcing his "転向tenkoJapanese" (ideological conversion or recantation). This declaration caused a significant shock within political and intellectual circles. While incarcerated, he found solace in Chinese poetry, composing his own verses and studying the works of poets such as Cao Cao and Lu You. This deep engagement with classical Chinese literature later bore fruit in works like Appreciation of Lu Fangweng (陸放翁鑑賞Riku Hōō KanshōJapanese), published after his release.

1.8. Post-Release Life and Literary Pursuits

Hajime Kawakami was released from prison in the early hours of June 15, 1937. His sentence had been reduced by one year and three months due to an amnesty, meaning he served three years and nine months. Upon his release, he met with newspaper reporters at his home but refrained from speaking directly. Instead, he released a written statement, transcribed by his family, which declared, "I close my life as a Marxist scholar with this release from prison."

Following his release, Kawakami dedicated himself to writing, including his comprehensive autobiography, Jijoden (自叙伝JijodenJapanese "Autobiography"). This work was secretly written between 1943 and 1945 and serialized posthumously in 1946. It became a best-seller and was widely praised as an unprecedented achievement in Japanese literature. In 1941, he relocated from Amanuma in Suginami-ku, Tokyo, to Kyoto. Besides his autobiography, he spent the remainder of his life translating Das Kapital from German into Japanese, although only a portion of the first volume was completed. He also continued to be a prolific writer, producing numerous essays, novels, and poetry.

2. Thought and Writings

Kawakami's intellectual output was vast and varied, reflecting his deep engagement with economic theory, social issues, and personal reflection.

2.1. Economic Theories

Hajime Kawakami's economic theories primarily revolved around a critical analysis of capitalism through a Marxist lens. He was a pioneer in introducing and interpreting Marxist economics in Japan, notably translating Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman's Economic Interpretation of History, which served as an early introduction to dialectical materialism in the country. His early work, Poverty Tale, while not fully Marxist, highlighted the stark realities of poverty and wealth disparity, advocating for a societal shift towards frugality to alleviate suffering. However, this initial proposition was criticized by contemporary economists and socialists for being idealistic and impractical, prompting Kawakami to delve deeper into the complexities of Marxist theory.

He later developed more sophisticated critiques of capitalism, emphasizing the inherent contradictions and exploitative mechanisms within the system. Kawakami's interpretations of Marxist economics, particularly as presented in works like Outline of Economics and Introduction to Das Kapital, were instrumental in shaping the development of theoretical economics in Japan during the 1920s and 1930s. He argued that the fundamental problems of capitalism, such as poverty and economic crises, could not be resolved by superficial measures like overcoming deflation, as he asserted during the Shōwa Depression. Instead, he believed that a fundamental transformation of the economic system was necessary to achieve social justice and economic equality. His lectures and writings significantly influenced a generation of students and workers, spreading Marxist thought across Japan.

2.2. Major Works

Hajime Kawakami was a prolific writer whose works spanned economic theory, social commentary, and personal narrative. His major contributions include:

- Poverty Tale (貧乏物語Binbō MonogatariJapanese, 1917): This best-selling work critically examined the issue of poverty in Japan. While it initially proposed that the wealthy should abandon luxury to solve poverty, it served as a significant social commentary and introduced early Marxist ideas to a broad audience, sparking widespread public debate on wealth disparity.

- Second Poverty Tale (第二貧乏物語Daini Binbō MonogatariJapanese, 1930): Published later, this work delved deeper into Marxist analysis, serving as a more direct introduction to Marxist principles and their application to understanding poverty, widely read by the masses.

- Outline of Economics (経済学大綱Keizaigaku TaikōJapanese, 1928): This academic work played a crucial role in establishing and developing theoretical economics in Japan, particularly in popularizing Marxist economic thought within academic circles.

- Introduction to Das Kapital (資本論入門Shihonron NyūmonJapanese, 1929): A foundational text for understanding Marxist economics in Japan, this work simplified complex concepts from Karl Marx's Das Kapital, making them accessible to a wider readership.

- Jijoden (自叙伝JijodenJapanese, "Autobiography", 1947): Written secretly during his later years and published posthumously, this autobiography is celebrated for its literary quality and candid reflections on his life, intellectual journey, and political struggles. It became a best-seller and was highly acclaimed.

- Appreciation of Lu Fangweng (陸放翁鑑賞Riku Hōō KanshōJapanese, 1949): This work, developed from his studies during imprisonment, showcases his deep appreciation for classical Chinese poetry, particularly the works of Lu You (Lu Fangweng).

Kawakami also produced extensive collected works, including the 12-volume Hajime Kawakami Collected Works (河上肇著作集Kawakami Hajime ChosakushūJapanese, 1964-1965) and the 28-volume Hajime Kawakami Complete Works (河上肇全集Kawakami Hajime ZenshūJapanese, 1982-1984), followed by a 7-volume continuation. He was also a prolific translator of key economic and philosophical texts, including works by Leo Tolstoy, Adolf Wagner, Nicolaas Pierson, Frank Fetter, Irving Fisher, Karl Marx (such as Wage Labour and Capital and Wages, Price and Profit), Nikolai Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin, and Friedrich Engels (co-translating The German Ideology).

3. Personal Life

Hajime Kawakami's personal life was intertwined with his public and intellectual pursuits. His father was Kawakami Tadashi, a samurai from Yamaguchi Prefecture. His mother, Tazu, was the second daughter of Kawakami Matasaburo and the younger sister of Kawakami Kin'ichi. Notably, his mother was divorced from his father nine months into her pregnancy with Hajime. He also had a half-brother, Kawakami Nobusuke, who was the son of his father's second wife; his father's second marriage also ended in divorce three months after Nobusuke's birth. His younger brother, Sakyo Kawakami, was a painter who notably designed the cover for Hajime's influential work, Poverty Tale.

In 1902, Kawakami married Hide (秀Japanese, 1885-1966), the daughter of Kenzaburo Otsuka. Hide was also the younger sister of Takeshi Otsuka and the elder sister of Yushō Otsuka. Through her, Kawakami was the grandson of Baron Hikaru Inoue. Hajime and Hide had three children: one son and two daughters. Their eldest son tragically passed away while attending university. Their eldest daughter, Shizu, married Nikio Hamura, a professor at Kyoto Imperial University. Their second daughter, Yoshi (also known as Yoshiko Kawakami), became an underground activist and served as a housekeeper for her maternal uncle, Yushō Otsuka, who was also a member of the Japanese Communist Party. Yushō Otsuka described Kawakami as "truly honest, inflexible, capable of concentrating his spirit on one point to the point of appearing narrow-minded." Hajime Kawakami's brother-in-law was Hiroshi Suekawa, who was married to Hide's sister. Hide herself documented her experiences in a book titled Rusudō Nikki (留守日記Rusudō NikkiJapanese, "Diary of Absence"), and her life was also the subject of a novel by Yaeko Kusakawa, Runaway Horse: Hajime Kawakami's Wife.

4. Evaluation and Impact

Hajime Kawakami's multifaceted career as an economist, activist, and writer left a lasting impact on Japanese society, economics, and literature.

4.1. Scholarly and Social Contributions

Kawakami is widely recognized for his significant scholarly contributions, particularly as a pioneer of Marxist economics in Japan. His efforts to translate and popularize Marxist theories, especially through works like Introduction to Das Kapital and Outline of Economics, were crucial in shaping the discourse of theoretical economics in the country during the 1920s and 1930s. His lectures at Kyoto Imperial University were highly influential, inspiring a generation of students and intellectuals. Beyond academia, Kawakami actively engaged in social reform movements, using his writings, most notably Poverty Tale, to highlight and critique social inequalities and advocate for economic justice. His ability to articulate complex economic issues in an accessible manner made his work resonate with a broad audience, leading to best-selling publications and widespread public discussion on poverty and wealth disparity. Furthermore, his literary accomplishments, including his acclaimed autobiography Jijoden and his skill as a Chinese poet, cemented his reputation as a versatile and impactful intellectual figure.

4.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his significant contributions, Kawakami's life and work were not without criticism and controversy. His early economic theories, particularly the initial solution proposed in Poverty Tale-that the wealthy should abandon luxury to eliminate poverty-were sharply criticized by contemporaries like Tokuzo Fukuda and socialist Toshihiko Sakai for being unrealistic and lacking practical applicability. Later, his interpretations of Marxism faced scrutiny, notably from Minzō Kushida of the Rōnō-ha faction, who argued that Kawakami's understanding of Marxism was flawed. Kawakami, to his credit, acknowledged the validity of some of these criticisms, which spurred him to deepen his study of Marxist theory.

His political affiliations and activities, especially his involvement with the outlawed Japanese Communist Party and subsequent underground work, led to his arrest and imprisonment under the Public Security Preservation Law. The most significant controversy surrounding his life was his "転向tenkoJapanese" (ideological conversion or recantation) while in prison. His public statement from jail, declaring his withdrawal from all practical political activities and closing his life as a Marxist scholar, sent shockwaves through the intellectual and political communities. This "tenko" was viewed by some as a capitulation to state pressure, while others saw it as a complex personal decision made under duress, reflecting the intense ideological pressures of the time.

4.3. Legacy

Hajime Kawakami's enduring influence on Japanese society is multifaceted. He is remembered as a foundational figure in the development of Marxist economics in Japan, having introduced and popularized complex theories that shaped academic discourse and social movements for decades. His writings on poverty and social inequality continued to inspire generations of activists and thinkers concerned with economic justice. The widespread popularity of his works, particularly Poverty Tale and his autobiography Jijoden, underscores his lasting literary legacy and his ability to connect with the public on profound social issues. Despite the controversies surrounding his political activities and "tenko," Kawakami's commitment to social critique and his intellectual rigor ensured his place as a pivotal figure in modern Japanese intellectual history, whose ideas continued to be studied and debated long after his death.

5. Death

Hajime Kawakami died on January 30, 1946, at his home in Sakyo-ku, Kyoto. His death was attributed to a combination of old age, malnutrition, and pneumonia. He had planned to resume his activities after the end of World War II but succumbed to his ailments shortly thereafter. His posthumous Buddhist name is Tenshin'in Shōjin Nichijō Koji. His autobiography, Jijoden, which he had written in secret during his final years, was published in 1947, becoming a widely read and celebrated work after his passing.