1. Life

Guo Xi's life saw him transition from a relatively unknown background to a celebrated court painter, though his later years were marked by a shift in artistic appreciation and a decline in his prominence after the passing of his imperial patron.

1.1. Early Life and Background

Guo Xi was born in 1023 in Wen County, Henan Province, during the early period of the Northern Song dynasty. Details of his early life and family background are limited, but he is known by his courtesy name, Chunfu (淳夫Chinese). His foundational artistic training and initial development are not extensively documented, but his eventual rise to prominence in the imperial court suggests a significant period of dedicated study and practice.

1.2. Court Activities

Guo Xi's career flourished beginning in the early years of Emperor Shenzong's reign. He was appointed to the imperial court, where he held significant positions such as a scholar-artist post in the Imperial Academy and later ascended to the highest rank for a calligraphy and painting technician, becoming a Daizhao (chief technician). Under Emperor Shenzong's patronage, Guo Xi created numerous large-scale murals and screens for imperial offices, palaces, and temples. His innovative style and grand compositions deeply impressed the young emperor, who reportedly took special care to ensure Guo Xi's artistic freedom, allowing him to work outside the confines of the traditional Imperial Painting Academy. This special arrangement underscored Shenzong's appreciation for Guo Xi's unique talent and his desire to foster an environment where the artist's genius could fully manifest.

1.3. Later Years

After Emperor Shenzong's death, Guo Xi's activities in the court diminished. With the loss of his main patron, his artistic style, which was highly technical and often focused on grand, decorative effects, gradually diverged from the prevailing aesthetic sensibilities of the literati class. The literati, who increasingly favored a more understated, spontaneous, and intellectually driven approach to painting, found Guo Xi's intricate style less appealing. There are anecdotes from the Huaji (Record of Paintings) by Deng Chun indicating that many of Guo Xi's large-scale murals and screens were eventually removed from the palace and treated as discarded items during the reign of Emperor Huizong. Despite his earlier fame, Guo Xi faced a period of being overlooked in his later years, leading up to his death in 1085.

2. Artistic Style and Techniques

Guo Xi developed a distinctive landscape painting style characterized by innovative compositions and a deep understanding of natural phenomena, profoundly influencing subsequent generations of Chinese artists.

2.1. View of Nature and Artistic Philosophy

Guo Xi approached nature not merely as a subject to be copied, but as a living entity to be intimately experienced and understood. His philosophical approach emphasized the importance of direct observation and personal immersion in the natural world. He famously articulated this by stating, "The best way to understand nature is to personally wander and observe these mountains, so that the landscape appears vividly in one's mind." This belief underpinned his artistic practice, leading him to create landscapes that conveyed not just the physical appearance of mountains and rivers, but also their inherent spirit and changing moods. He recognized that the mists and vapors of real landscapes vary significantly across the four seasons: light and diffused in spring, rich and dense in summer, scattered and thin in autumn, and dark and solitary in winter. Similarly, he observed the mountains themselves presenting different visages: light and seductive in spring, verdant in summer, bright and tidy in autumn, and sad and tranquil in winter. This deep appreciation for nature's nuances allowed him to imbue his paintings with a sense of life and atmospheric vitality.

2.2. Major Painting Techniques

Guo Xi is celebrated for perfecting several landscape painting techniques that became hallmarks of his style and influenced later artists. Among his most notable innovations is the "Three-distance method" (三遠法Chinese), which integrates multiple perspectives into a single composition:

- Pingyuan (平遠Chinese): "Horizontal distance," depicting a flat, expansive view.

- Gaoyuan (高遠Chinese): "High distance," an elevated or high-angle perspective, looking down from a peak.

- Shenyuan (深遠Chinese): "Deep distance," a deep or receding perspective, looking into a valley or chasm.

These three perspectives allowed him to create a sense of vastness and depth, making his landscapes immersive and dynamic. He also developed distinctive brushstrokes such as "Cloud-head Wrinkle" (雲頭皴Yun-tou cunChinese), which involves short, rounded, and overlapping brushstrokes to depict the texture of rocks and mountains, resembling cloud formations. Another signature technique is "Crab-claw Trees" (蟹爪樹Xie-zhao shuChinese), where the branches of his depicted trees splay out in a sharp, angular manner, reminiscent of crab claws, conveying a sense of struggle and resilience, especially in winter scenes.

Guo Xi also employed an "angle of totality," sometimes referred to as "Floating Perspective," which allows the viewer's eye to move freely through the composition, observing the scene from multiple, non-static viewpoints. This technique differentiates Chinese spatial representation from the single-point perspective common in Western art. Furthermore, he was a master at expressing changes in light, mist, and the four seasons, using layered ink washes and amorphous brushstrokes to model surfaces and suggest the veiling effects of the atmosphere. His ability to depict the subtle shifts from morning to evening, and from clear skies to rain, added an unprecedented sense of realism and temporal depth to his landscapes.

3. Major Works

Guo Xi's artistic legacy is primarily defined by his masterful landscape paintings, which captured the essence of nature with profound depth and innovative techniques. Among his most acclaimed works are "Early Spring," "Snow Mountain" (also known as "Deep Valley"), and "Autumn in the River Valley."

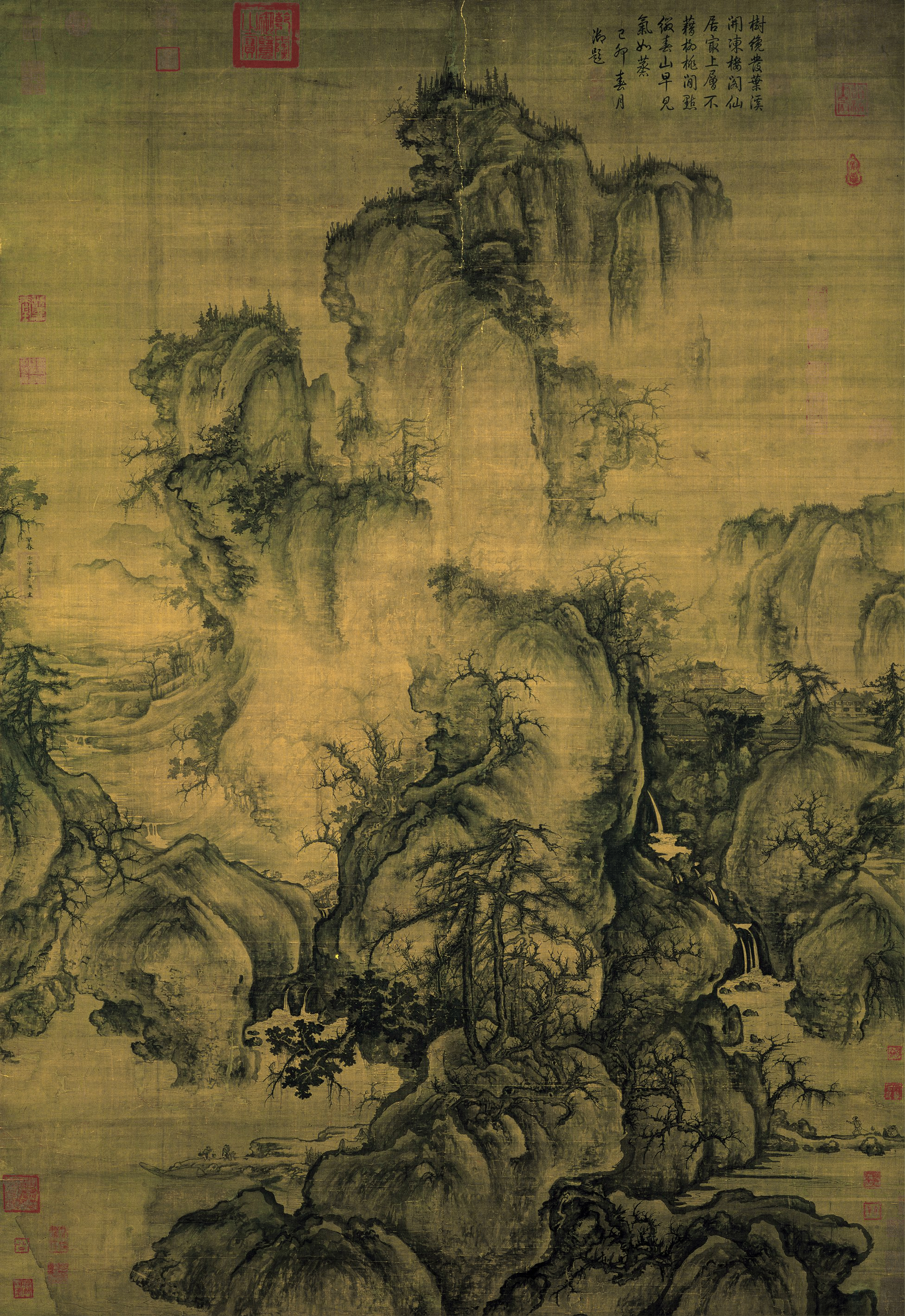

One of his most famous masterpieces is Early Spring, dated 1072. This painting exemplifies his "angle of totality" or "Floating Perspective," allowing the viewer's eye to traverse the intricate details of the landscape from various viewpoints simultaneously. The work showcases a monumental composition with towering peaks, winding streams, and delicate trees, all enveloped in a misty atmosphere that conveys the nascent energy of spring. The intricate details, from the texture of the rocks rendered with "Cloud-head Wrinkle" to the expressive "Crab-claw Trees," demonstrate his command of brushwork and his ability to evoke the season's unique light and spirit.

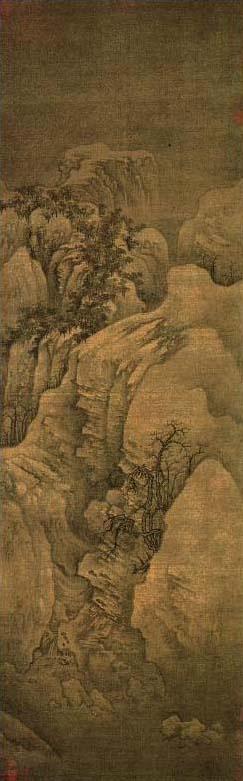

Another significant work is Snow Mountain, also known as Deep Valley, which is part of the collection of the Shanghai Museum. This scroll painting depicts a serene mountain valley heavily covered with snow, where old trees struggle to survive on precipitous cliffs. Guo Xi masterfully uses light ink washes and magnificent composition to express an open and profound artistic conception. The amorphous brush strokes effectively model surfaces, suggesting the veiling effects of the cold, misty atmosphere characteristic of winter.

Autumn in the River Valley (sometimes referred to as The Coming of Autumn) is another painting attributed to Guo Xi that skillfully captures the distinctive atmosphere of the autumn season. Like Early Spring, this work demonstrates his ability to convey the transient beauty of nature through changes in light, color, and mood. These paintings are regarded as pivotal accomplishments of the Song Dynasty, showcasing Guo Xi's innovative techniques and his deep connection to the natural world. Another notable work attributed to him is Old Trees, Level Distance, currently housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which showcases his detailed portrayal of aged trees and expansive, flat landscapes.

4. Writings and Treatises on Art

Guo Xi's profound artistic philosophy and practical insights were codified in a highly influential treatise titled The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams (林泉高致Linquan GaozhiChinese).

This significant text is primarily attributed to Guo Xi, but it was compiled and edited by his son, Guo Si (郭思Chinese), who meticulously recorded his father's teachings and observations. The treatise covers a wide array of themes central to landscape painting, offering detailed guidance on the appropriate methods for depicting mountains, rivers, trees, and atmospheric conditions. It elaborates on his famous "Three-distance method" and provides insights into his philosophical approach to understanding and representing nature. The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams is not merely a technical manual but also a philosophical discourse on the painter's relationship with nature and the spiritual dimensions of art. It emphasizes that a painter must achieve a deep empathy with the landscape to truly capture its essence, encouraging artists to wander and observe mountains intimately until their forms vividly unfold within their minds. This treatise had a profound and lasting impact on subsequent Chinese art theory, serving as a foundational text for later generations of landscape painters and critics who sought to understand and extend the principles of Northern Song aesthetics.

5. Later Assessment and Influence

Guo Xi's contributions to Chinese art were multifaceted, establishing a significant school of thought and influencing countless artists, despite facing periods of criticism and neglect.

5.1. Influence on Contemporary and Later Art Circles

Guo Xi, alongside his predecessor Li Cheng, formed a formidable partnership in the history of Chinese landscape painting, leading to the establishment of the "Li-Guo School" (李郭派Chinese). This school became one of the two major stylistic lineages in Chinese landscape painting, standing alongside the "Dong-Ju style" (董巨風格Chinese) of Dong Yuan and Juran. The Li-Guo School was characterized by its emphasis on dramatic, monumental compositions, often depicting tall, slender trees with distinct "crab-claw" branches, and employing a range of innovative brushwork to capture the textures of rocks and mountains, often enveloped in atmospheric mists. Guo Xi's unification and synthesis of the ideals and styles of earlier northern landscape masters like Li Cheng and Fan Kuan culminated in a comprehensive system of painting that profoundly shaped the aesthetics of the Northern Song dynasty. His detailed system of idiomatic brushstrokes and his innovative compositional approaches became essential for subsequent painters, extending his influence well beyond his lifetime. Many later artists were inspired by his work, and some even dedicated their own landscapes to his style.

5.2. Historical Assessment and Criticism

During his lifetime, Guo Xi received high praise from some of the most esteemed literati and officials of the Northern Song court, including the renowned poet Su Shi, the calligrapher Huang Tingjian, and the statesman Wang Anshi. These contemporary figures recognized the artistic brilliance and innovative spirit in his work. However, following the death of his imperial patron, Emperor Shenzong, Guo Xi's artistic fortunes shifted. His highly refined and technical style, which had once been celebrated for its grandeur and decorative qualities, began to fall out of favor with the rising literati class. This class increasingly prioritized a more understated, natural, and intellectually profound approach to painting, often favoring expressive brushwork over intricate detail. The anecdote of his works being removed from the palace during Emperor Huizong's reign reflects this changing aesthetic landscape and a period where his contributions were perhaps undervalued or even forgotten. Despite these later criticisms and periods of neglect, Guo Xi's artistic legacy has been re-evaluated over time, and he is now recognized as one of the most important landscape painters in Chinese history. His enduring influence on artistic theory through The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams and his innovative techniques continue to be studied and appreciated for their significant contribution to the development of Chinese art.

6. Personal Life and Working Methods

Guo Xi's dedication to his art was profound, and his working methods reflected a deeply contemplative and meticulous approach, as recounted by his son, Guo Si.

His son described a ritualistic process that Guo Xi would undertake before beginning a painting session. On days when he intended to paint, Guo Xi would carefully prepare his workspace. He would seat himself at a clean table situated by a bright window, ensuring optimal light. To create an atmosphere conducive to artistic creation, he would burn fragrant incense to his right and left. He was particular about his tools, selecting only the finest brushes and the most exquisite ink. Before beginning, he would wash his hands and meticulously clean his ink-stone, performing these actions with the same reverence as if he were preparing to receive a visitor of high rank. Crucially, he would wait until his mind achieved a state of complete calm and stillness, ensuring he was entirely undisturbed by external distractions. Only after achieving this inner tranquility would he begin to paint. This detailed account highlights Guo Xi's disciplined approach, emphasizing that for him, painting was not merely a technical skill but a spiritual and meditative practice that required a prepared mind and an environment of serenity. This personal commitment to the artistic process undoubtedly contributed to the depth and expressive quality of his renowned landscape works.