1. Early Life and Background

George Brown's early life in Scotland and his subsequent move to New York City laid the groundwork for his future career in journalism and politics, exposing him to both entrepreneurial endeavors and public discourse.

1.1. Scotland

George Brown was born in Alloa, Clackmannanshire, Scotland, on November 29, 1818. He was the eldest son of Peter Brown and Marianne Mackenzie, whose father, George Mackenzie, was a nobleman from Stornoway on the island of Lewis. Peter Brown managed a large wholesale business in Edinburgh and was also involved in directing a glassworks in Alloa. George's family returned to Edinburgh before he turned eight. He attended the renowned Royal High School and later the Southern Academy of Edinburgh, taking pride in his connection to Scotland's national capital. After graduating with awards, George joined his father's business instead of attending university, briefly living in London to receive training from the business's agents before returning to Edinburgh. He became a member of the Philo-Lectic Society of Edinburgh, a forum where young men engaged in parliamentary-style debates.

In addition to his business ventures, Peter Brown worked as a tax collector for the municipality. In 1836, some municipal funds, which had been mixed with his business bank accounts, were lost in business speculations. While Peter was not accused of corruption, he sought to restore his reputation and recover the lost funds. His attempts to collect debts were hindered by the onset of the economic depression in 1837. Consequently, Peter decided to emigrate to New York City in search of new business opportunities and to rebuild his financial standing. George accompanied his father, departing Europe in May 1837.

1.2. New York City

The Browns arrived in New York in June 1837. Peter opened a dry goods store on Broadway, with George assisting him. The following year, George's mother and sisters joined them in New York, and the family resided in a rented home on Varick Street. As the dry goods store expanded, George traveled extensively to New England, Upstate New York, and Canada to further develop their business.

In July 1842, Peter Brown launched the British Chronicle, a newspaper promoting a Whig-Liberal political ideology, initially focusing on British news and politics. As its circulation increased in Canada, the paper began to include articles on political developments within the Province of Canada. In March 1843, George assumed the role of the paper's publisher, continuing to travel across New England, Upstate New York, and Canada to promote it. During his time in Canada, he engaged with politicians and editors in Toronto, Kingston, and Montreal. It is believed that George also contributed articles to the paper, with a series titled "A Tour of Canada" showing a writing style consistent with his later works.

Peter Brown was a strong supporter of the evangelical faction during the Disruption of 1843 within the Church of Scotland. In May 1843, these members separated to form the Free Church of Scotland. While George was touring Canada, he received an offer from members of the Free Church: a bond of 2.50 K USD if his father would relocate the publication of the British Chronicle to Upper Canada. George strongly endorsed this proposal, believing that Canada offered greater opportunities for success and noting a perceived hostility towards the paper in New York due to its focus on British affairs. His interactions with Reform politicians during his travels in Canada further convinced him that they would support his newspaper if it moved to the province. George persuaded his father, and the final issue of the British Chronicle was published on July 22, 1843, before their move to Canada.

2. Journalism Career in Canada

George Brown's journalism career in Canada was marked by the establishment and growth of highly influential newspapers, cementing his role as a powerful media proprietor and political commentator.

2.1. Founding of The Globe and Influence

After arriving in Toronto, George and Peter Brown rented a storefront and, on August 18, 1843, published the inaugural edition of their new newspaper, Banner. George managed the secular department, focusing on non-religious issues. Initially, Banner did not formally align with any political party, though it supported many policies advocated by Reformers. This changed dramatically when the Governor-General of the province, Charles Metcalfe, prorogued the Reform-dominated Canadian assembly after several Reform politicians resigned. On December 15, George published a scathing editorial critical of the Governor-General's actions. In subsequent weeks, Banner continued to publish editorials refuting political accusations against Reformers and calling for unity behind Liberal candidates in upcoming elections.

In 1844, Reformers, concerned that Tories would leverage loyalty to the British monarch to sway voters in the upcoming legislative election for the Province of Canada, sought to establish newspapers to disseminate their ideas. They offered Brown 250 GBP to start a new publication. In March, Brown launched The Globe, serving as both its editor and publisher. Two months later, he acquired a rotary press, the first of its kind in Upper Canada, significantly boosting printing efficiency and enabling him to expand into book publishing and printing services. Although his primary focus shifted to politics, Brown continued writing for Banner and traveled to Kingston in July to report on the Canadian Synod for the Church of Scotland. Following the meeting, he joined the committee of Free Kirks in Kingston, who sought to secede from the Church of Scotland. That autumn, Brown actively campaigned for Reform candidates in communities surrounding Toronto, even persuading Caleb Hopkins to withdraw his candidacy in Halton to prevent splitting the Reform vote. Brown himself declined to run, prioritizing his father's financial debts and the improvement of his newspapers. Despite his efforts, the Reformers were largely unsuccessful in the election, with many prominent members failing to secure seats in the legislature.

In the summer of 1845, Brown put his father in charge of The Globe and traveled to Southwestern Ontario to boost subscriptions. He discovered that a rival Reform newspaper, Pilot, was undercutting his prices, making it difficult to attract new subscribers. Brown appealed to Reform leaders, who convinced Francis Hincks, the editor of Pilot, to raise his paper's cost. In October, Brown launched the Western Globe in London, Canada West, which combined editorials from The Globe with local stories from the southwestern region. By 1846, The Globe began publishing semi-weekly, marking it as the first Reform newspaper in Toronto to do so.

During the 1848 Province of Canada legislative election, Hincks was preoccupied with business in Montreal and unable to campaign in Oxford county for his re-election. Brown spoke on Hincks's behalf at the nomination meeting, contributing to his successful re-election. The Reformers secured a majority of seats in the election, forming an administration led by Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine. In July 1848, Brown and his father closed Banner to concentrate entirely on expanding The Globe and their publishing business.

In the summer of 1848, the administration appointed Brown to lead a Royal Commission investigating accusations of official misconduct at the Provincial Penitentiary in Portsmouth, Canada West. His report, drafted in early 1849, meticulously documented widespread abuse by prison staff. Brown recommended structural changes, including separating juvenile, first-time, and long-term prisoners, and hiring prison inspectors. During the investigation, the prison's Board of Inspectors resigned, and Brown, alongside Adam Fergusson and William Bristow, assumed their roles. Initially volunteers, Brown and Bristow later received payment, becoming the first government inspectors in this capacity. By October 1853, The Globe began printing daily issues, asserting that it had achieved the largest circulation in British North America.

3. Early Political Career

Brown's entry into politics marked a significant period of advocacy and reform, as he quickly became a leading voice within the Reform movement and engaged in critical policy debates.

3.1. Involvement in Reform Movement and Early Elections

In 1848, the Reformers secured a majority in the Province of Canada legislature, leading to the formation of an administration under co-premiers Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine. By the following year, disagreements over the secularization of clergy reserves, the potential annexation of the Province of Canada by the United States, and the influence of Reformers involved in the Upper Canada Rebellion led to the formation of two distinct factions within the Reform movement. Brown remained aligned with the core Reform party, while others branched off to form the Clear Grit movement. In May 1850, he joined the Toronto Anti-Clergy Reserves Association, advocating for the abolition of clergy reserves. He believed that promoting this policy would prevent further Reform defections to the Clear Grits, even if French-Canadian reformers might not fully support such measures.

In April 1851, Brown contested a byelection to represent Haldimand County in the Canadian parliament but was defeated by William Lyon Mackenzie. In the subsequent parliamentary session, Baldwin and Lafontaine announced their retirement from politics, and Hincks assumed leadership of the western Reform movement. This period saw a renewal of the rivalry between Hincks and Brown, with Hincks criticizing The Globe for its opposition to state support for religious institutions. In the fall of 1851, Brown acquired agricultural land in Kent County, Upper Canada, intending to pursue farming. Later that year, Reformers in Kent County, including Alexander Mackenzie and Archibald McKellar, encouraged Brown to run in the upcoming Canadian parliament election for the Kent County constituency. Brown accepted, despite planning to campaign against the current Reform ministry's policy of state support for religious institutions. His campaign also championed representation by population, free trade agreements with British colonies and the United States, and the development of crucial transportation infrastructures such as railways and canals. Brown ultimately won the election as an independent Reform candidate, defeating Arthur Rankin, the ministry-approved Reformer, and a Tory opponent.

3.2. Political Debates and Stances

Brown supported an administration led by Hincks and Augustin-Norbert Morin as successors to the Baldwin-Lafontaine government, though he openly criticized the government for abandoning liberal ideals. He tirelessly worked to end state support for religious institutions, vehemently opposed government funding for a religious separate school system, and steadfastly endorsed representation by population in the legislature. His newspaper, The Globe, maintained widespread circulation, and on October 1, it began publishing daily as The Daily Globe to compete with other newspapers that had already adopted daily publication. Brown's support eroded when scandals against Hincks emerged in the fall of 1853, prompting Brown to tour Canada West, demanding new leadership for the Reform party. For the 1854 general election, his constituency was divided into two, and he chose to run in Lambton, uncertain of his chances in the other Kent constituency. Following the election, Hincks formed a new Liberal-Conservative administration with Allan MacNab, leading Brown to assume a role within the opposition.

Brown collaborated with his opposition colleagues, including former Clear Grit rivals, Reformers who had abandoned Hincks, and the Parti Rouge, to criticize the governing coalition. Through these efforts, Brown emerged as one of the unofficial leaders of the opposition. He further consolidated his influence by acquiring two Grit-aligned newspapers and merging their staffs with The Globe. In May 1855, the Canadian legislature passed a bill authorizing the creation of Roman Catholic-based separate school boards in Upper Canada. This was widely perceived as French-Canadian encroachment into Upper Canadian affairs, as the bill passed without the support of the majority of Upper Canadian parliamentarians. Brown seized upon this event to campaign vigorously for representation by population, arguing for electoral districts to be apportioned based on population to ensure equal representation. Brown's pursuit of this goal, which he viewed as correcting a grave injustice to Canada West, was at times accompanied by stridently critical remarks against French Canadians and the perceived power wielded by the Catholic population of Canada East over the predominantly anglophone and Protestant Canada West. Despite these strong sentiments, he did not advocate for the dissolution of the Canadas, as a significant portion of Canada West's trade flowed through Canada East via the Saint Lawrence River, and a split would grant the eastern province control over this vital waterway before it entered Canada West.

In 1855, Brown organized and provided the necessary credit for the development of the town of Bothwell, within his Lambton constituency, also setting aside farmland for his personal use. In 1856, John A. Macdonald publicly accused Brown of falsifying evidence and coercing witnesses during the 1848 Royal Commission on the Kingston Provincial Penitentiary. A subsequent committee of inquiry produced a report that remained non-committal regarding Brown's guilt. Macdonald's accusations and the ensuing investigation deepened the political rivalry between Brown and Macdonald.

3.3. 1857 Election and Subsequent Legislature

Brown played a key role in organizing a political convention on January 8, 1857, aiming to unite his followers with the Clear Grits and Liberals who had departed the Hincks administration. Brown served as one of the "joint secretaries of the local committee" for this meeting. This convention marked a significant shift for the Reform party, moving away from radicalism towards a political ideology more closely aligned with liberal principles in Britain. The meeting successfully adopted a new political platform for the Reformers, largely based on Brown's political positions and those articulated in his newspaper.

An election for the Parliament of the Province of Canada was held in November 1857. Brown initially hesitated to run for the Lambton seat, as constituency concerns consumed too much of his time, and he wished to focus on broader Reform party matters. He accepted the candidacy nomination for North Oxford, expecting fewer constituency demands, and as it consistently elected Liberal candidates, it would allow him to campaign for other Liberal candidates across the province. Simultaneously, a petition circulated in Toronto urging Brown to run for one of its two seats. This petition garnered support from groups that traditionally did not back Reform candidates, such as Orangemen, who felt Conservative candidates were overly cooperative with French Canadians. Brown decided to run in both constituencies, dedicating most of his attention to the Toronto campaign. He was elected in both constituencies, and his Reformers secured the majority of seats in Canada West. However, his allies in the Parti Rouge were unsuccessful in Canada East, leading Brown to return to the legislature as an opposition member.

In the legislative session following the election, Brown served as the de facto leader of the opposition. On July 28, 1858, the cabinet of the Macdonald-Cartier administration resigned after the legislature rejected Ottawa as the new permanent capital of the province. Edmund Walker Head, the Governor-General of Canada, then asked Brown to form a new administration. Lacking a majority of support in the legislature, Brown negotiated a cabinet under a co-premiership with Antoine-Aimé Dorion. As required by law, Brown and the other members of his cabinet resigned their seats in parliament to run in a by-election. On August 2, parliament passed an amendment disapproving of the administration, prompting Brown to request a general election from Head. Head declined Brown's request, and on August 4, Brown resigned as co-Premier. Macdonald and Cartier were subsequently able to form a new ministry with Alexander Tilloch Galt.

On August 28, Brown won the by-election necessitated by his brief appointment to the cabinet during the Brown-Dorion administration. He then toured the province, delivering speeches at various Reform gatherings that strongly denounced the Cartier-Macdonald administration. In the 1859 Toronto mayoral election, the first where the electorate directly voted for the mayor, Brown organized the Municipal Reform Association to nominate Adam Wilson as the Reformer candidate; Wilson ultimately won the election against his Conservative opponents.

In 1859, Brown and other Upper Canadian Reformers organized a convention in Toronto to discuss the governance of the province. Their hope was that agreeing on a unified policy would prevent further divisions within the movement on this issue. Brown advocated for creating a federalist system that would grant provinces more control over their governance, believing this system would deter American encroachment into British North American territory west of Upper Canada and curb what he perceived as Conservative corruption exemplified by the administration. Brown's speech at the convention, supporting a federal government, was positively received by the delegates, who passed resolutions endorsing his preferred policy positions. On April 30, 1860, Brown proposed a bill in the Province of Canada's legislature to form a convention to discuss federalism. Although the bill was defeated, the vote documented the Reformer's support for federalism, and Brown successfully convinced the majority of Reformers to back his resolution.

Throughout this period, Brown continued to operate and invest in various business ventures across Upper Canada. In The Globe, he announced a new layout for the paper that allowed more text to be printed on each page, made possible by investments in new, copper-faced type. In Kent, he sold some acres of his land and a cabinet factory to recover from financial difficulties, but he found profit in his mills, which sold hardwood to American lumber-dealers.

4. Confederation

George Brown's pivotal involvement in the Great Coalition and his participation in key conferences were instrumental in shaping the framework for Canadian Confederation, reflecting his strong advocacy for federalism and national unity.

4.1. Participation in the Great Coalition and Conferences

Brown's health began to decline in 1859, with residual effects continuing into 1860, exacerbated by the stress of leading the Reform faction in parliament and growing financial concerns with his businesses. His health deteriorated further, leading him to stay in bed for over two months during the winter of 1861, causing him to miss the entire parliamentary session. An election took place later that year, where the Toronto Reform Association nominated Brown as their candidate for the Toronto East constituency. Despite his health not being fully recovered, Brown struggled to campaign effectively, though he managed to deliver passionate speeches towards the end of the campaign. He also faced challenges regarding his limited success in enacting proposed policies during his tenure as a legislator. His Conservative opponent, John Willoughby Crawford, campaigned on similar policy promises, arguing that as a member of the ruling party, he would be better positioned to achieve goals that Brown, as an opposition legislator, had struggled to realize. Crawford won the election, ending Brown's time as a legislator.

Although Conservative factions secured another majority of seats in parliament, their position was precarious, with only a few votes against the government capable of disbanding it. Despite his electoral defeat, Brown remained a recognized leader of the Liberal movement in Western Canada. He engaged with his Liberal counterparts in Eastern Canada about forming a government should the Conservative coalition be defeated. When his inquiries were rejected, Brown took the opportunity to withdraw from public life, declining requests to speak at rallies. In 1862, still afflicted by illness, Brown decided to recuperate in Great Britain. He spent a month in London, where he had a chance encounter with Tom Nelson, a former schoolmate from Royal High School. Nelson persuaded Brown to visit him in Edinburgh, where Brown met Nelson's sister, Anne. Brown moved to a location near the Nelson home and began courting Anne. Five weeks after their first meeting, on November 27, 1862, they were married at the Nelson's home. The couple departed for Toronto just over a week later.

With his health restored, Brown desired to return to politics, though he committed to his wife that his political involvement would be temporary and not his primary career, as she wished to spend more time with him. In March 1863, a by-election was called for the South Oxford constituency, and Reformers selected Brown as their candidate, despite his unfamiliarity with the riding's specific concerns. Brown won the by-election and reassumed a leadership position within the Reform party. He was re-elected during the July 1863 general election, where Reformers secured a majority of seats in Canada West, while Conservatives won the majority in Canada East. This electoral outcome created a political deadlock in the legislature, making governance of the province extremely difficult.

Brown proposed the formation of a select committee to investigate the sectional problems within Canada and seek a solution. The bill for the committee's creation passed in the spring of 1864. Under Brown's chairmanship, the committee reported on June 14, expressing a strong preference for a new federal system of government. On the very same day, the Macdonald-Taché administration was dissolved. Brown publicly stated his willingness to support any administration committed to resolving the legislative deadlock. Subsequently, Brown, Macdonald, Taché, and George-Étienne Cartier agreed to form an administration later known as the Great Coalition, with the explicit goal of pursuing a federal union with the Atlantic provinces. Brown accepted the position of President of the Council, a cabinet-level role, under the premiership of Taché.

4.2. Advocacy for Federalism and Negotiations

Brown attended the Charlottetown Conference, where Canadian delegates outlined their proposal for Canadian Confederation with the Atlantic provinces. On September 5, 1864, Brown presented the proposed constitutional structure for the union. The conference accepted the proposal in principle, and Brown participated in subsequent meetings in Halifax, Nova Scotia and Saint John, New Brunswick to finalize the details of the union.

During the Quebec Conference, Brown strongly advocated for separate provincial and federal governments. He believed that establishing distinct provincial governments would effectively address and remove local concerns from the federal level, which he felt were more politically divisive. He also argued for an appointed Senate, based on his view that upper houses were inherently conservative and served to protect the interests of the wealthy. He deliberately sought to deny the Senate the legitimacy and power that typically accompany an electoral mandate, also expressing concern that two elected legislative bodies could lead to political deadlock, particularly if different parties held majorities in each. The Quebec Conference concluded with the formulation of the Quebec Resolutions. Brown presented these resolutions in a significant speech in Toronto on November 3. Later that month, he traveled to England to initiate discussions with British officials regarding Canadian Confederation, the integration of the North West Territories into Canada, and the defense of British North America against potential American invasion.

Brown recognized that achieving satisfaction for Canada West necessitated the support of the French-speaking majority in Canada East. In his speech advocating for Confederation in the Legislature of the Province of Canada on February 8, 1865, he spoke enthusiastically about Canada's future prospects. He emphatically stated, "whether we ask for parliamentary reform for Canada alone or in union with the Maritime Provinces, the views of French Canadians must be consulted as well as ours. This scheme can be carried, and no scheme can be that has not the support of both sections of the province." Although he had initially supported the idea of a legislative union at the Quebec Conference, Brown was eventually persuaded to favor the federal view of Confederation. This approach, which was closer to that supported by Cartier and the Bleus of Canada East, ensured that the provinces retained sufficient control over local matters, satisfying the French-speaking population's need for jurisdiction over issues deemed essential to their survival. Despite this shift, Brown remained a proponent of a stronger central government with weaker constituent provincial governments.

In May and June 1865, Brown was part of a delegation sent to London to continue discussions on Confederation with British officials. The British government agreed to support Canadian Confederation, to defend Canada in the event of an American attack, and to assist in establishing a new trade agreement with the United States. In September, Galt and Brown represented the Province of Canada at the Confederate Trade Council, a gathering of Canadian colonies convened to negotiate common trade policies following the termination of their reciprocity trade agreement with the United States. During the meeting, Brown engaged with Maritime delegates to garner support for Canadian Confederation, as enthusiasm for the project was waning in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. He also supported the council's resolution to pursue trade policies that would reduce tariffs with the United States. However, the administration for the Province of Canada disagreed, seeking instead to increase tariffs on American goods. Frustrated by this divergence with his cabinet colleagues, Brown resigned from the Great Coalition on December 19.

Following his resignation, Brown sought to rebuild relationships with his Rouge colleagues to strengthen the Reform party's political prospects in Canada West. He subsequently lost an election in Southern Ontario for a seat in the new legislature. Brown concluded that too many Reformers had aligned with Macdonald and the Conservatives during the Great Coalition, and that the public largely supported this non-partisan administration. He declined to run in other, safer constituencies and instead embarked on a holiday to Scotland.

5. Post-Confederation Political Activities

Following Confederation, George Brown continued his significant contributions to Canadian public life, albeit outside the immediate legislative spotlight. He remained a leader within the Liberal Party, pursued important international trade negotiations, and managed various business ventures.

5.1. Liberal Party Leadership and Reciprocity Treaty

In 1866, Brown purchased an estate called Bow Park near Brantford, Upper Canada, where he engaged in the herding of shorthorn cattle. He continued his active role in journalism, writing and editing The Globe, and was frequently consulted by Grit officials on matters concerning both provincial and Canadian politics. Throughout his career, from 1843 to 1872, Brown engaged in numerous disputes with the typographical union, ultimately being compelled to pay union wages after intense negotiations and strikes.

In 1874, Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie appointed Brown to negotiate a new reciprocity treaty with the United States. Brown engaged in negotiations with the United States Secretary of State Hamilton Fish from February until June 18, when a draft treaty was proposed in the US Congress. However, the Congress did not pass the bill into law, and it was set aside when Congress adjourned just four days after the treaty's proposal.

5.2. Senate Appointment and Business Ventures

Brown was appointed to the Canadian Senate in 1874 and attended his first session the following year. He provided crucial support to Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie when Edward Blake and the Canada First movement expressed their frustrations with Mackenzie's leadership. Brown's attendance in the Senate was sporadic, as his primary focus remained on the business affairs of his ranch. In February 1876, he traveled to England to raise capital for a new cattle-raising company, successfully obtaining a charter for the venture upon his return to Canada in May. Despite his efforts, the company struggled financially, and two fires in December 1879 destroyed many of the buildings on his property, compounding his business difficulties.

6. Personal Life

George Brown married Anne Nelson on November 27, 1862, in Edinburgh, just five weeks after their initial meeting. The couple promptly departed for Toronto shortly after their wedding. Together, they had two daughters, Margaret and Catherine, who notably became among the first women to graduate from the University of Toronto in 1885.

7. Death

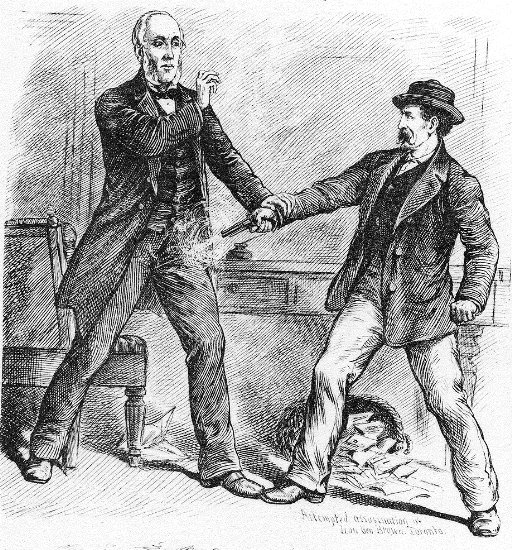

In 1880, The Globe was facing significant financial challenges as Brown had invested heavily in updating the newspaper's printing press to produce multi-page and machine-folded papers. On March 25, 1880, a former Globe employee named George Bennett entered Brown's office. Bennett, who had recently been fired by a foreman, demanded a certificate proving his five years of employment with the newspaper. Brown, not recognizing Bennett, directed him to speak with the foreman. An argument ensued, during which Bennett produced a gun. As Brown attempted to seize the weapon, it discharged, firing a bullet into Brown's thigh. Bennett was subsequently apprehended by other individuals present, and the wound was initially deemed minor. Brown left his office and retired to his Toronto home to recover. However, his leg became infected, leading to a fever and delirium. George Brown died at his Toronto home on May 9, 1880. He was buried at Toronto Necropolis. Bennett was subsequently charged with murder and was later hanged.

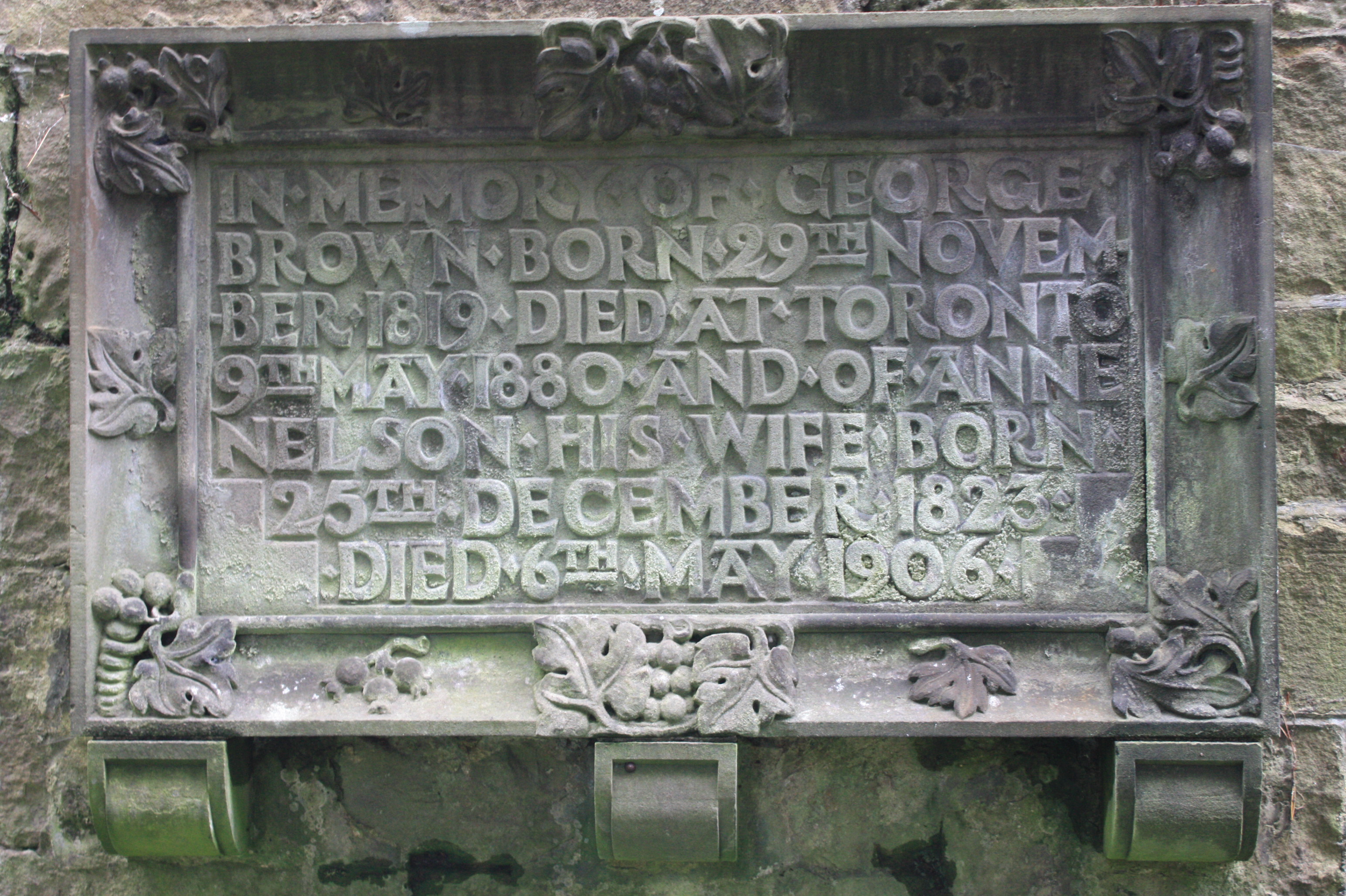

Following George Brown's death, his wife, Anne Nelson, returned to Scotland, where she passed away in 1906. She is interred on the southern terrace of Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh, and her grave also commemorates George Brown.

8. Political Philosophy and Views

George Brown's political philosophy was deeply influenced by his religious upbringing and his vision for a unified and progressive Canada. He held strong views on the separation of church and state, social justice, and the structure of national governance.

8.1. Views on Social Issues and National Unity

Brown was raised as a member of the Church of Scotland. Historian J. M. S. Careless described the family's faith as being closer to the tenets of the evangelical movement of the 1800s rather than a strict Calvinist interpretation of the bible. Brown advocated for a Puritan separation between politics and religion, believing that true political liberty could only be achieved if religious institutions were not involved in political affairs. While he maintained that everyone should be Christian, he believed that political institutions should not exert influence over religion. However, in 1850, despite his general opposition to state funding for religions through clergy reserves, he was willing to tolerate it to maintain the crucial allegiance between Upper Canadian Reformers and French Canadian Catholic Reformers.

Brown was a staunch opponent of slavery, viewing the enslavement of people in the American southern states as the greatest flaw of the United States. He was an active participant in the Elgin Association, a group primarily composed of Free Kirk individuals who purchased land in Kent County to establish a settlement for escaped slaves. Through his editorials in The Globe, he also defended a settlement of escaped slaves in Buxton from hostile white inhabitants in Kent. Additionally, Brown served as an executive member of the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada, further demonstrating his commitment to human rights and social justice.

Throughout the existence of the Province of Canada, Brown consistently advocated against dissolving the union. In the 1850s, he feared that a dissolution would disrupt trade along the Saint Lawrence River, a major thoroughfare, if two separate jurisdictions imposed differing rules on their respective sections of the river. He worried that farmers west of Upper Canada might then opt to use the Erie Canal in the United States, a route with a single set of regulations, potentially leading to American annexation of those lands. Instead, Brown proposed a federal union that would exercise jurisdiction over joint concerns, while allowing each section to create laws for its own territory. Brown particularly advocated for representation by population as a means to ensure that the French population did not wield disproportionate power. He aimed to preserve the defensive and trade advantages that a unified province would offer and sought to incorporate the Maritime provinces into the union, envisioning a stronger, more cohesive nation.

9. Legacy and Assessment

George Brown's legacy is profoundly ingrained in Canadian history, evident in the institutions bearing his name and his lasting contributions to the nation's political development, though his career also faced its share of controversies.

9.1. Honors and Institutions

Brown's former residence, known as Lambton Lodge and now as George Brown House, located at 186 Beverley Street in Toronto, was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1974. It is currently managed by the Ontario Heritage Trust and serves as a conference center and offices. Brown also maintained an estate, Bow Park, near Brantford. Acquired in 1826, it operated as a cattle farm during Brown's lifetime and functions as a seed farm today.

In recognition of his contributions, George Brown College in Toronto, founded in 1967, was named after him. Statues commemorating George Brown can be found on the front west lawn of Queen's Park in Toronto (erected in 1910) and on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, the latter sculpted by George William Hill in 1913. His historical significance was also recognized when he was portrayed by Peter Outerbridge in the 2011 CBC Television film John A.: Birth of a Country. Furthermore, George Brown's image appeared on a Canadian postage stamp issued on August 21, 1968, marking his enduring presence in the national memory.

9.2. Criticism and Controversy

While celebrated for his significant contributions to Canadian journalism and the establishment of Confederation, George Brown's political career was not without its criticisms and controversies. His stridently critical remarks against French Canadians and the perceived influence of the Catholic population of Canada East often stirred contention and highlighted a tension within his vision for national unity. Although he ultimately compromised on a federal structure to accommodate French-Canadian concerns within Confederation, his earlier pronouncements were sources of significant political friction. His disputes with the typographical union, which sometimes led to tense negotiations and strikes that forced him to pay union wages, also present a complex facet of his legacy, showing his entrepreneurial interests clashing with labor demands. These aspects reflect the challenges and complexities inherent in his efforts to shape a diverse and unified Canada.

10. Electoral Record

| 1867 Canadian federal election: South riding of Ontario | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | |

| Liberal-Conservative | Thomas Nicholson Gibbs | 1,292 | |

| Liberal | George Brown | 1,223 | |