1. Early Life and Education

Georg Wilhelm Steller's early life and academic pursuits laid the foundation for his distinguished career as a naturalist and explorer.

1.1. Childhood and Family Background

Steller was born on 10 March 1709, in Windsheim, near Nuremberg in the Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Germany). He was the son of Johann Jakob Stöhler, a Lutheran cantor. Around 1715, Georg changed his last name from Stöhler to Steller to better accommodate Russian pronunciation, a change that would become permanent.

1.2. Education

Steller began his formal education at the University of Wittenberg. He later pursued a wide range of studies at the University of Halle, where he delved into theology, philosophy, medicine, and the natural sciences. This diverse academic background equipped him with the interdisciplinary knowledge essential for his future expeditions and scientific contributions.

2. Career and Expeditions

Steller's professional journey began with his entry into the Russian scientific community, leading to his pivotal role in the monumental Second Kamchatka Expedition and his subsequent explorations.

2.1. Joining the Russian Academy of Sciences

In November 1734, Steller arrived in Russia as a physician aboard a troop ship returning with wounded soldiers. He officially joined the Imperial Academy of Sciences in 1734 as a physician. During this period, he met the renowned naturalist Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt (1685-1735). Two years after Messerschmidt's death, Steller married his widow, through whom he gained access to Messerschmidt's extensive notes from his travels in Siberia, which had not yet been submitted to the Academy.

2.2. Second Kamchatka Expedition

Steller learned of Vitus Bering's Second Kamchatka Expedition, which had departed Saint Petersburg in February 1733. Eager to contribute, he volunteered to join and was accepted. He left Saint Petersburg in January 1738, though his wife chose to remain in Moscow and not continue the journey. In January 1739, Steller met Johann Georg Gmelin in Yeniseisk, who recommended Steller to take his place in the planned exploration of Kamchatka. Steller embraced this new role and finally reached Okhotsk and the main expedition in March 1740, just as Bering's ships, the St. Peter and St. Paul, were nearing completion.

2.2.1. Voyage to Alaska

In September 1740, the expedition sailed to the Kamchatka Peninsula, with Bering and his two vessels navigating around the peninsula's southern tip and up to Avacha Bay on the Pacific coast. Steller went ashore on the east coast of Kamchatka to spend the winter in Bolsherechye. There, he actively participated in organizing a local school and began his initial explorations of the Kamchatka region. When Bering summoned him to join the voyage in search of America and the strait between the two continents, Steller, serving as the expedition's scientist and physician, crossed the peninsula by dog sled.

After the St. Peter was separated from its sister ship, the St. Paul, in a severe storm, Bering continued sailing east, expecting to find land soon. Steller, however, carefully observed sea currents, flotsam, and wildlife, insisting that they should sail northeast. After considerable time was lost due to Bering's initial reluctance, they finally turned northeast and made landfall in Alaska at Kayak Island on Monday, 20 July 1741. Bering initially intended to stay only long enough to replenish fresh water. Steller, recognizing the immense scientific opportunity, successfully argued Captain Bering into granting him more time for land exploration, securing a mere ten hours. Steller famously remarked on the mathematical irony of "10 years preparation for ten hours of investigation."

Although the crew never set foot on the mainland due to Bering's perceived stubbornness and "dull fear," Georg Steller is credited with being one of the first non-natives to have set foot on Alaskan soil. During his brief time on land, Steller became the first European naturalist to describe a number of North American plants and animals, including a distinctive blue-crested bird later named Steller's jay.

2.2.2. Shipwreck and Survival

During the arduous return journey, the crew suffered greatly from a growing scurvy epidemic. Steller attempted to treat the ailment using leaves and berries he had gathered, but his proposals were largely scorned by the officers. Notably, Steller and his assistant were among the very few who did not contract the disease, likely due to their adherence to his dietary recommendations.

With only 12 members of the crew still able to move and the ship's rigging rapidly failing, the expedition was tragically shipwrecked on what later became known as Bering Island. Almost half of the crew had perished from scurvy during the voyage. Steller diligently nursed the survivors, including Bering, but the commander could not be saved and died on the island. The remaining men established a camp with scarce food and water, a dire situation exacerbated by frequent raids from Arctic foxes. To survive the harsh winter, the crew resorted to hunting sea otters, Steller sea lions, northern fur seals, and Steller's sea cows. Steller took a leading role in organizing the surviving crew and their eventual escape from the uninhabited island.

2.3. Exploration of Kamchatka Peninsula and Commander Islands

In early 1742, the shipwrecked crew ingeniously used salvaged materials from the St. Peter to construct a new, smaller vessel, which they nicknamed The Bering. With this makeshift ship, they successfully returned to Avacha Bay. After his return, Steller spent the next two years extensively exploring the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Commander Islands, meticulously documenting their natural history and geography.

3. Scientific Contributions

Georg Wilhelm Steller's scientific contributions were profound, marked by his meticulous documentation and classification of countless new species, as well as his valuable ethnographic observations.

3.1. Documentation and Classification of Flora and Fauna

Steller's expeditions, particularly the Second Kamchatka Expedition, were instrumental in expanding Western scientific knowledge of the North Pacific's biodiversity. He meticulously documented numerous plants and animals, many of which were previously unknown.

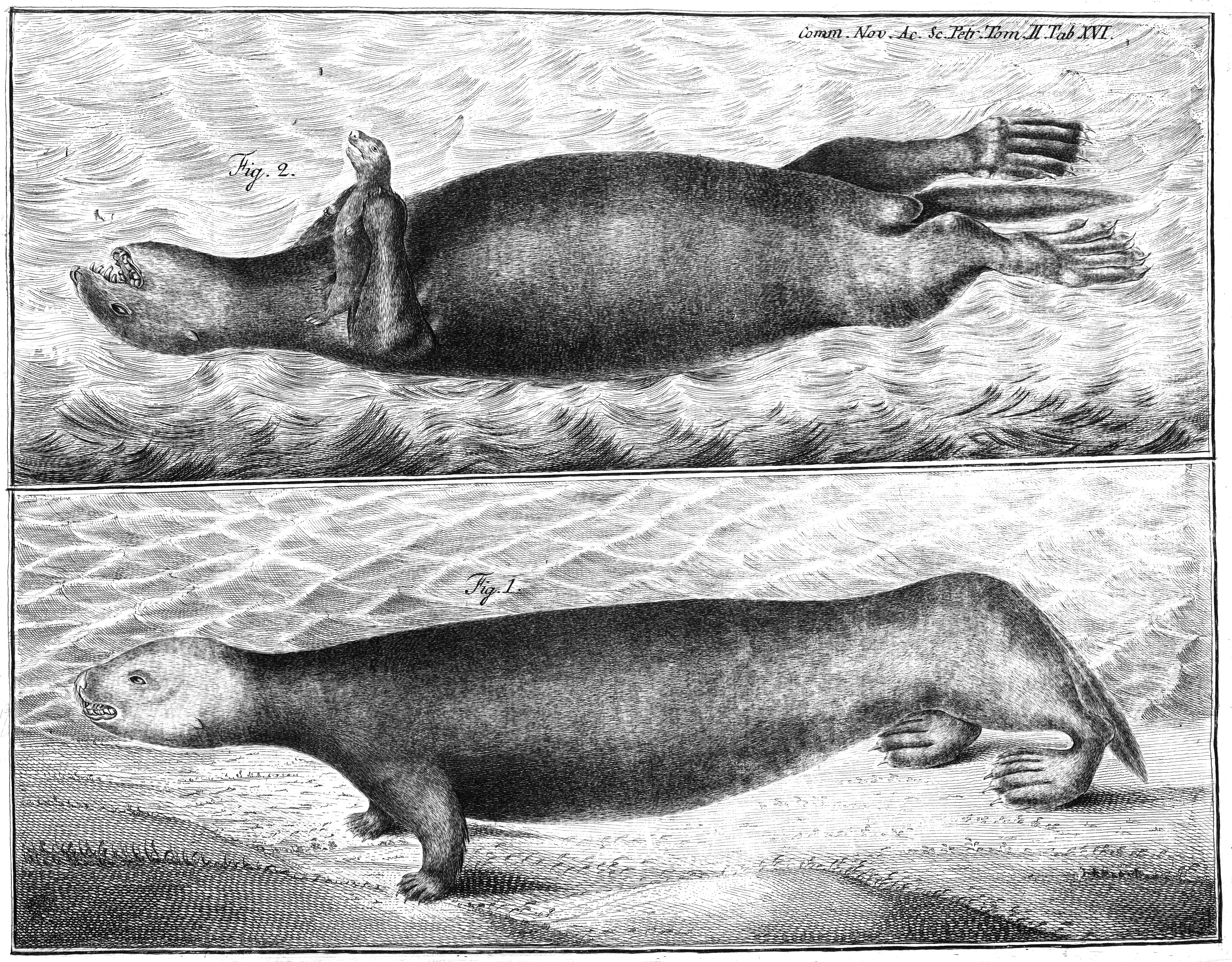

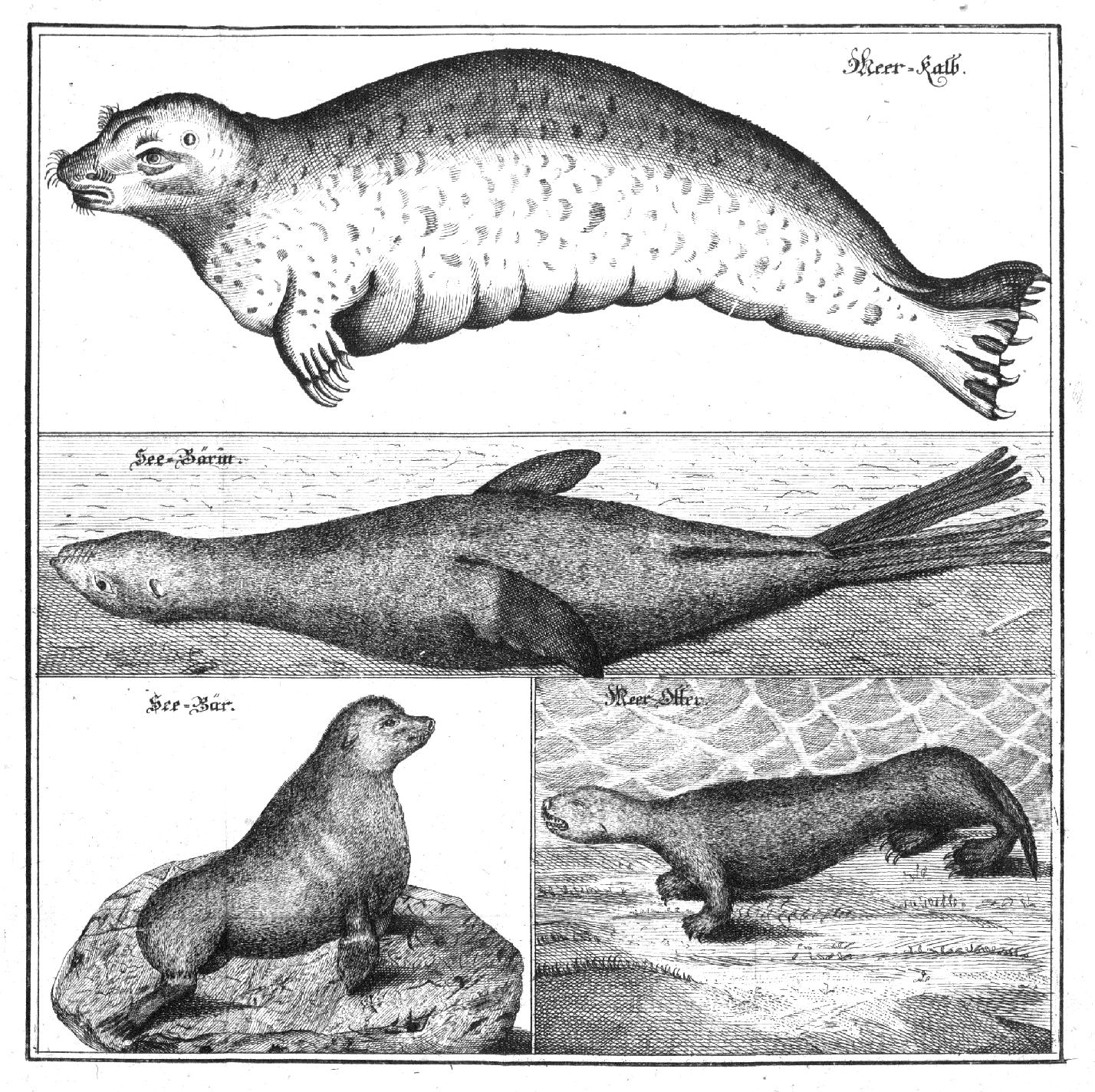

3.1.1. Marine Mammals

Steller made groundbreaking discoveries and detailed descriptions of several marine mammals. Among his most significant findings was the Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), a massive sirenian mammal, a northern relative of the dugong. This species, which once ranged across the Northern Pacific during the Ice Ages, had a relict population confined to the shallow kelp beds around the Commander Islands. Steller's detailed behavioral and anatomical observations of the sea cow remain the only known accounts of this animal. Tragically, the Steller's sea cow, discovered and named by Steller, lasted only 27 years after its discovery, becoming a victim of overhunting by Russian crews who followed in Bering's wake, and was extinct by 1768.

Other marine mammals first described or named by Steller include the Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus), the sea otter (Enhydra lutris), and the northern fur seal.

3.1.2. Birds

Steller also discovered and documented several bird species. The Steller's sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) and Steller's eider (Polysticta stelleri) are among the notable birds he described. He also documented the spectacled cormorant, a species that, like the Steller's sea cow, later became extinct.

The Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) is one of the few species named after Steller that is not currently listed as endangered. In his brief encounter with the bird, Steller was able to deduce its kinship to the American blue jay, a fact that provided crucial proof that Alaska was indeed part of North America.

3.1.3. Other Species

Beyond marine mammals and birds, Steller's comprehensive studies included various other flora and fauna. These include the Steller's sculpin (Myoxocephalus stelleri), the gumboot chiton (Cryptochiton stelleri), and the hoary mugwort (Artemisia stelleriana). He also identified the plant genera Stellera L. (in the family Thymelaeaceae) and Restella Pobed. (also in Thymelaeaceae). Steller also claimed the only recorded sighting of the marine cryptid known as Steller's sea ape.

3.2. Ethnographic Observations

Steller's scientific curiosity extended beyond flora and fauna to the human populations he encountered. He meticulously recorded his observations of the indigenous peoples, particularly the Itelmens of Kamchatka. His journals contain valuable ethnographic details about their culture, customs, and daily lives, making him a significant ethnographer for the region.

4. Personal Life

Beyond his scientific endeavors, Steller's personal life included his marriage to the widow of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt. However, his wife did not accompany him beyond Moscow when he departed for the Second Kamchatka Expedition.

5. Death

After his extensive explorations, Steller was falsely accused by a jealous rival of freeing Kamchadal rebels from prison and was recalled to Saint Petersburg. He was subsequently placed under arrest and compelled to return to Irkutsk for a hearing. Though he was eventually freed and began his journey back west towards Saint Petersburg, he fell ill with a fever and died on 14 November 1746, in Tyumen, Siberia, at the age of 37. A memorial to Steller was erected in a riverside park in Tyumen in 2009.

6. Legacy and Evaluation

Georg Wilhelm Steller's legacy is multifaceted, encompassing his profound influence on scientific exploration, the numerous species and places named in his honor, and the critical evaluation of the long-term impact of his discoveries.

6.1. Species and Places Named After Steller

Steller's significant contributions to natural history are commemorated by numerous animals, plants, minerals, and geographical features bearing his name.

Animals and plants named after him include:

- Steller's eider (Polysticta stelleri)

- Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri)

- Sea otter (Enhydra lutris)

- Steller's sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus)

- Short-tailed albatross or Steller's albatross (Phoebastria albatrus)

- Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)

- Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus)

- Steller's sculpin (Myoxocephalus stelleri)

- Gumboot chiton (Cryptochiton stelleri)

- Hoary mugwort (Artemisia stelleriana)

- Stellera L. (a plant genus in the family Thymelaeaceae)

- Restella Pobed. (a plant genus in the family Thymelaeaceae)

In the mineral kingdom, Stellerite (a mineral in the zeolite group) is named in his honor. Geographical features include Steller's Arch on Bering Island and Mount Steller at q=58.429722, -154.391389|position=right. The Steller Secondary School in Anchorage, Alaska, is also named for him.

6.2. Impact on Scientific Exploration

Steller's discoveries and meticulously kept records had a profound influence on subsequent scientific exploration of the North Pacific. His journals, many of which were published posthumously by Peter Simon Pallas, became invaluable resources for later explorers, including Captain Cook. Steller's work significantly advanced the understanding of North Pacific natural history, providing a foundational baseline for future research into the region's unique biodiversity. He is widely regarded as a pioneer of Alaskan natural history.

6.3. Historical Evaluation and Criticism

The historical evaluation of Steller's scientific achievements is complex. While his detailed documentation provided unprecedented insights into the natural world of the North Pacific, his discoveries inadvertently contributed to the tragic extinction of certain species. Of the six species of birds and mammals that Steller discovered during his voyage, two are now extinct: the Steller's sea cow and the spectacled cormorant. Three others are classified as near threatened or vulnerable: the Steller sea lion, Steller's eider, and Steller's sea eagle.

The Steller's sea cow, in particular, was driven to extinction within 27 years of its discovery. Steller's reports, which provided the first detailed accounts of these animals, ironically led to their rapid overhunting by Russian crews. Consequently, Steller's books and journals became the sole source of information on the ecology and behavior of the Steller's sea cow, highlighting the unintended negative consequences that can arise from scientific reporting without immediate conservation measures.

6.4. Cultural Impact

Steller's life and achievements have resonated in popular culture, literature, and the arts. He is referenced in "Xmas With the Skanks Adventure" (s3e10) of The Great North, where a character names a reindeer "Wilhelm" after the zoologist. T. Edward Bak's graphic novel Wild Man - vol. 1: Island of Memory: The Natural History of Georg Wilhelm Steller (2013) tells the story of Steller's journeys, intertwining his social connections and context. Steller is also the subject of the second section of W. G. Sebald's book-length poem, After Nature (2002), and a somewhat fictionalized account of his time with Bering is contained in James A. Michener's novel, Alaska.

7. Works

Georg Wilhelm Steller authored several significant works and expedition journals, many of which were published posthumously, providing invaluable scientific and historical records.

7.1. Major Works

Steller's most representative work is De Bestiis Marinis ('On the Beasts of the Sea'), published in Latin in 1751 and in German in 1753 as Georg Wilhelm Stellers ausführliche Beschreibung von sonderbaren Meerthieren, mit Erläuterungen und Nöthigen Kupfern versehen. This work meticulously describes the fauna of the Commander Islands, including the northern fur seal, the sea otter, Steller sea lion, Steller's sea cow, Steller's eider, and the spectacled cormorant. The Japanese source notes that some of the harsh expressions regarding the crew's behavior found in his posthumously published works might be due to the lack of his own proofreading.

7.2. Expedition Journals

Steller's expedition journals provide detailed accounts of his voyage with Vitus Bering during the Second Kamchatka Expedition (1741-1742). These journals, such as the Journal of a Voyage with Bering, 1741-1742, published by Stanford University Press in 1988, offer critical insights into the scientific observations, daily life, and challenges faced during the monumental journey. These records were later used by other explorers of the North Pacific, including Captain Cook, and are considered vital historical and scientific documents.

8. Related Items

During the shipwreck and subsequent survival on Bering Island, Steller's empirical knowledge of medicine proved crucial. He was able to save many crew members from scurvy through his understanding of local flora and their medicinal properties, despite initial skepticism from the officers.