1. Early Life and Background

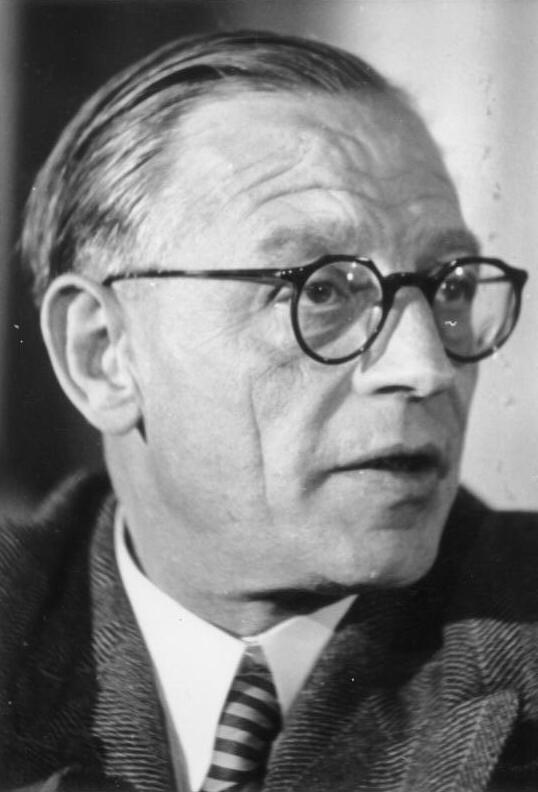

Georg Dertinger was born on December 25, 1902, in Berlin, Germany. He grew up in a middle-class Protestant family. Following his early education, Dertinger pursued higher studies, briefly focusing on law and economics.

2. Early Career and Political Leanings

After completing his studies, Dertinger embarked on a career in journalism. He initially worked as a journalist and later held editorial positions at the Magdeburger Volkszeitung and the nationalistic newspaper Der Stahlhelm. Despite his involvement with Der Stahlhelm, he eventually distanced himself from the organization due to its rigid right-wing philosophy. During this period, Dertinger expressed sympathy for the German National People's Party, a prominent right-wing nationalist political party in Germany.

3. Pre-World War II Activities

Dertinger became associated with the political circle surrounding Chancellor Franz von Papen. In his capacity as a journalist, representing the Hamburger Nachrichten, Dertinger accompanied Papen to Rome for the signing of the Reichskonkordat between Nazi Germany and the Holy See. This event occurred shortly after Adolf Hitler's rise to power. In 1934, Dertinger returned to Berlin, where he assumed the role of publisher for Dienst aus Deutschland, a news agency primarily responsible for providing news to foreign newspapers.

4. Post-War Political Activities in East Germany

Following World War II, Georg Dertinger played a foundational role in the establishment of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) within the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. His influence within the party grew rapidly, leading to his appointment as General Secretary of the East German CDU from 1946 to 1949. Subsequently, he served as the party's Vice-Chairman from 1949 until 1953. Dertinger was a strong proponent of the official policy of cooperation with the Socialist Unity Party (SED), which increasingly dominated the political landscape of the nascent East German state. His support for this alignment led him to oppose more independent-minded figures within the CDU.

4.1. Role within the East German Christian Democratic Union (CDU)

Within the East German CDU, Dertinger was instrumental in shaping the party's direction towards closer alignment with the SED. He notably opposed Jakob Kaiser, who served as the party chairman and held more independent views regarding the CDU's role in the Soviet occupation zone. Dertinger played a significant part in Kaiser's eventual deposition from the chairmanship in December 1947. This event marked a crucial turning point, solidifying the CDU's path towards becoming a bloc party within the SED-controlled National Front. Beyond his party activities, Dertinger also became a member of the Cultural Association of the DDR (KulturbundGerman) and served on its Presidential Council, further integrating himself into the East German political and cultural establishment.

5. Activities as Foreign Minister

On October 11, 1949, Georg Dertinger was appointed as East Germany's first Minister of Foreign Affairs within Otto Grotewohl's inaugural cabinet. His tenure as Foreign Minister lasted until January 15, 1953. A significant action during his time in office was the signing of the Oder-Neisse Treaty with Poland in 1950, which formally established the borderline between East Germany and the Polish People's Republic. Despite holding this prominent position, Dertinger was largely perceived as a figurehead. His appointment was primarily intended to secure the CDU's participation in the SED-dominated National Front, lending an appearance of broader political representation. However, most critical foreign policy decisions were made by the SED leadership, often by his eventual successor, Anton Ackermann, rather than by Dertinger himself.

6. Arrest, Trial, and Imprisonment

On January 15, 1953, Georg Dertinger was arrested by East German authorities. The official grounds for his arrest were his allegedly harmful activities against the East German state. The following year, in 1954, Dertinger was subjected to a show trial on charges of espionage. During the trial, which lacked due process and was designed to produce a predetermined outcome, he was found guilty and subsequently sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. His arrest and conviction were part of a broader pattern of political purges within the East German regime, targeting individuals perceived as disloyal or insufficiently aligned with the SED's agenda.

7. Amnesty and Later Life

After spending over a decade in prison, Georg Dertinger was granted amnesty in 1964, leading to his release. Following his release, he spent his final years working for the Roman Catholic St. Benno publishing house. Georg Dertinger passed away on January 21, 1968, at the age of 65.

8. Assessment and Impact

Georg Dertinger's political career in East Germany offers a critical case study of the challenges to democratic principles and human rights in the early years of the German Democratic Republic. His journey from a journalist with conservative nationalist leanings to a key figure in the East German CDU, and ultimately its first Foreign Minister, highlights the complex political landscape of the Soviet occupation zone. His active support for cooperation with the SED and his role in the deposition of the more independent-minded Jakob Kaiser were instrumental in aligning the East German CDU with the ruling communist party, effectively transforming it into a compliant bloc party rather than an independent political force. This contributed to the suppression of genuine multi-party democracy in the GDR.

Despite his high-profile position as Foreign Minister, Dertinger's limited actual influence underscores the centralized power of the SED and the largely ceremonial nature of other political offices. His eventual arrest, trial, and harsh imprisonment on dubious charges of espionage serve as a stark reminder of the repressive tactics employed by the East German regime to eliminate perceived dissent and consolidate its control. Dertinger's fate exemplifies how individuals, even those who initially collaborated with the system, could be purged when they no longer served the regime's immediate political objectives. His career thus reflects the broader erosion of democratic freedoms and the systematic curtailment of human rights that characterized East German politics.