1. Early Life and Education

Eugene Kranz's early life and educational path provided the foundational experiences that shaped his remarkable career in space exploration.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Kranz was born on August 17, 1933, in Toledo, Ohio. He grew up on a farm that overlooked the Willys-Overland Jeep production plant, an early exposure to industrial innovation. His father, Leo Peter Kranz, was the son of German immigrants and served as an Army medic during World War I. Tragically, his father passed away in 1940 when Eugene was only seven years old. Kranz has two older sisters, Louise and Helen.

1.2. Education and Military Service

Kranz's interest in space exploration began at a young age. While attending Central Catholic High School, he wrote a thesis titled The Design and Possibilities of the Interplanetary Rocket, which explored the concept of a single-stage rocket to the Moon. After graduating from high school in 1951, he pursued higher education. In 1954, he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from Saint Louis University's Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology.

Following his academic achievements, Kranz received his commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. He completed pilot training at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas in 1955. Shortly after earning his pilot wings, Kranz married Marta Cadena, whose parents were Mexican immigrants who had fled Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. His military service included a deployment to South Korea, where he flew F-86 Sabre aircraft for patrol operations around the Korean DMZ. After completing his tour of duty in Korea, Kranz left the Air Force. He then joined the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, where he contributed to the research and testing of new Surface-to-Air (SAM) and Air-to-Ground missiles for the U.S. Air Force at its Research Center at Holloman Air Force Base. He was honorably discharged from the Air Force Reserve as a Captain in 1972.

2. NASA Career

Eugene Kranz's extensive career at NASA was marked by his progressive ascent through leadership roles and his profound impact on the operational methodologies of human spaceflight, particularly during the challenging Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs.

2.1. Early Roles

After his tenure at McDonnell Aircraft, Kranz joined the NASA Space Task Group, which was then located at the Langley Research Center in Virginia. Upon his arrival at NASA, Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft assigned him as a Mission Control procedures officer for the uncrewed Mercury-Redstone 1 (MR-1) test. Kranz famously dubbed this mission the "Four-Inch Flight" due to its failure to launch, a detail he recounted in his autobiography.

As Procedures Officer, Kranz was responsible for integrating Mercury Control operations with the Launch Control Team stationed at Cape Canaveral, Florida. He was instrumental in developing the critical "Go/NoGo" procedures, which dictated whether missions could proceed as planned or had to be aborted. Additionally, he served as a crucial communication link, effectively acting as a switchboard operator between the control center at Cape Canaveral and NASA's global network of fourteen tracking stations and two tracking ships, communicating via Teletype. Kranz performed this vital role for all crewed and uncrewed Mercury flights, including the Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) and Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) missions, which marked the first Americans in space and in orbit, respectively.

Following the MA-6 mission, Kranz was promoted to Assistant Flight Director for the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) flight involving astronaut Scott Carpenter in May 1962. This was his initial assignment as an Assistant Flight Director (AFD), working under Kraft, who was the Flight Director for MA-7. While the successful outcome of MA-7 was a collective effort by Mission Control, both Kranz and Kraft played major roles in its resolution. Kranz continued in this capacity for the remaining two Mercury flights and the first three Gemini missions.

2.2. Gemini Program

With the commencement of the Gemini flights, Eugene Kranz was promoted to the Flight Director level. His first shift as a Flight Director, famously known as the "operations shift," occurred during the Gemini 4 mission in 1965. This mission was notable for featuring the first U.S. EVA (spacewalk) and for achieving a duration of four days in space, significantly advancing American human spaceflight capabilities.

2.3. Apollo Program

Following his contributions to the Gemini program, Eugene Kranz continued to serve as a Flight Director on several key Apollo missions. His assignments included odd-numbered flights such as Apollo 1, Apollo 5, Apollo 7, and Apollo 9. Notably, he directed Apollo 5, which achieved the first (and only) successful uncrewed test of the Lunar Module.

Kranz was selected as one of the initial Flight Directors for the crewed Apollo missions. He had previously collaborated with McDonnell-Douglas, the contractor for the Mercury and Gemini projects. However, for the Apollo program, a new contractor, Rockwell International, was involved. Kranz noted that although Rockwell was a prominent entity in aeronautics at the time, they were new to and less familiar with the space industry.

Kranz was appointed as a division chief for Apollo, with his responsibilities encompassing comprehensive mission preparation, mission design, the meticulous writing of procedures, and the development of essential handbooks. He emphasized that the Apollo program was distinct from previous missions due to the critical constraint of time; unlike other missions that afforded ample development time, Apollo operated under tight deadlines. Kranz, alongside James Otis Covington, co-authored a section on the Flight Control Division of the Apollo program within the NASA book What Made Apollo a Success?, providing detailed insights into its operations. The

Mission Control logo itself, according to Kranz, is highly symbolic, embodying principles of commitment, teamwork, discipline, morale, toughness, competence, risk, and sacrifice. His leadership and meticulous approach were central to the success of these complex missions, culminating in his role as Flight Director for Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969, when the Lunar Module Eagle successfully landed on the Moon.

2.4. Apollo 13

Eugene Kranz is most widely recognized for his pivotal role as the lead Flight Director, specifically his "White Flight" team, during NASA's Apollo 13 crewed lunar landing mission. His team was on duty when a catastrophic explosion occurred in the Service Module of Apollo 13, initiating the critical hours of the unfolding accident.

Kranz's "White Team," famously dubbed the "Tiger Team" by the press, played an indispensable role in overcoming the crisis. They meticulously set the precise constraints for the consumption of critical spacecraft consumables, including oxygen, electricity, and water, which were vital for the crew's survival. Furthermore, they expertly controlled the three crucial course-correction burns during the trans-Earth trajectory and managed the complex power-up procedures that ultimately enabled the astronauts to safely land back on Earth in the Command Module. For their extraordinary efforts and dedication, NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine formally recommended Kranz and his team to President Richard Nixon for the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

2.5. Later Career and Retirement

Following his pivotal role in the Apollo 13 mission, Eugene Kranz continued to serve as a Flight Director through Apollo 17, with his final shift in this role overseeing the mission's liftoff. In 1974, he was promoted to Deputy Director of NASA Mission Operations, further advancing his leadership within the agency. He then assumed the role of Director in 1983, a position he held during significant events in space history.

Kranz was in Mission Control on January 28, 1986, when the Space Shuttle Challenger was lost during the STS-51-L launch, a somber moment in NASA's history. He retired from NASA in 1994, concluding a distinguished career after the successful STS-61 flight in 1993, which notably repaired the optically flawed Hubble Space Telescope.

3. Activities After Retirement

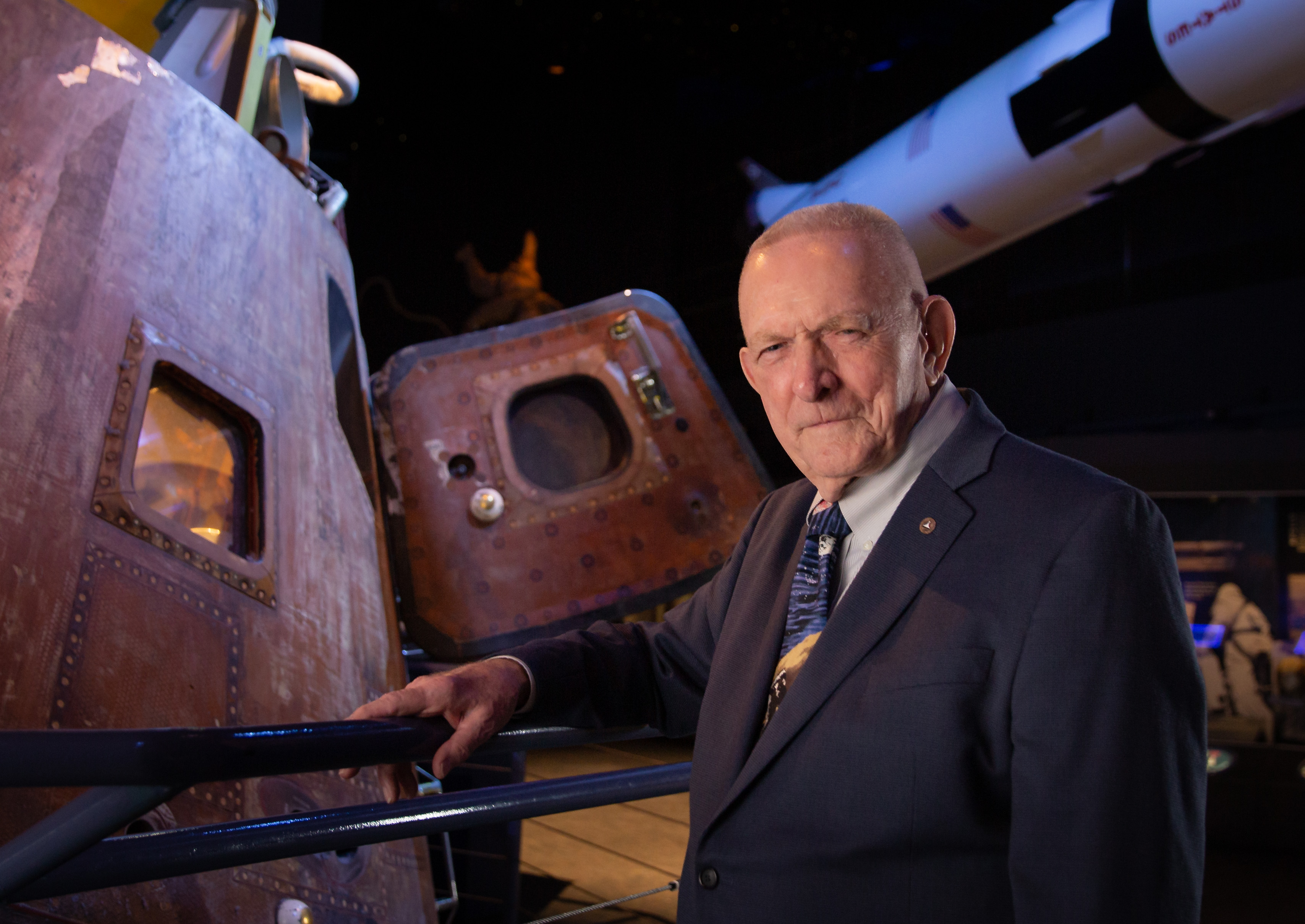

Following his retirement from NASA, Eugene Kranz remained an active figure, dedicating his efforts to advocacy for space exploration, public outreach, and the preservation of the historical legacy of mission control.

In 2000, Kranz published his autobiography, titled Failure Is Not An Option. The title famously borrowed from the line spoken by actor Ed Harris, who portrayed Kranz in the 1995 film Apollo 13. This book later served as the basis for a 2004 documentary about Mission Control produced by The History Channel.

Beginning in 2017, Kranz played a leading role in initiating and directing the restoration of the Mission Control Room at the Johnson Space Center. The goal was to restore the room to its appearance and functional state as it was during the Apollo 11 mission in 1969. This extensive project, costing 5.00 M USD, was intended to be completed in time for the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. In recognition of his significant efforts, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner declared October 23, 2018, as "Gene Kranz Day." During the 2018 "To the Moon and Beyond" luncheon hosted by Space Center Houston, the "Gene Kranz Scholarship" was established, aimed at providing funding for young students to participate in activities and training for careers in STEM fields. In the fall of 2019, the Ohio State Legislature introduced House Bill 358, proposing to designate August 17 as "Gene Kranz Day" in his home state. As of June 2020, the bill had passed the state house and was awaiting consideration by the state senate.

Beyond his work related to NASA's historical preservation, Kranz also actively participated in aviation. Post-retirement, he served as a flight engineer on a restored Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, flying at air shows across the United States for six years. He continues to deliver motivational speeches and share his experiences from the space programs, inspiring audiences with his insights on leadership, teamwork, and resilience.

4. Philosophy and Core Concepts

Eugene Kranz's career at NASA was defined not only by his technical expertise but also by a distinct philosophy and a set of core concepts that shaped the culture of mission control and continue to influence perspectives on human endeavor in complex environments.

4.1. "Tough and Competent" (Kranz Dictum)

The phrase "Tough and Competent" is a cornerstone of Eugene Kranz's legacy, often referred to as the "Kranz Dictum." This guiding principle originated during a pivotal moment in NASA's history: a meeting Kranz called with his branch and flight control team on the Monday morning following the devastating Apollo 1 disaster, which claimed the lives of astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee.

In his powerful address, Kranz articulated a profound expression of values and admonishments for the future of spaceflight. He declared that "Spaceflight will never tolerate carelessness, incapacity, and neglect." He acknowledged collective responsibility, stating, "Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up... We are the cause! We were not ready! We did not do our job." He emphasized that the problems, from non-functional simulators to constantly changing procedures, should have been addressed.

Kranz then defined the two words that would characterize Flight Control from that day forward: "Tough" and "Competent." He explained that "Tough" meant being "forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do," never compromising responsibilities, and knowing what they stood for every time they entered Mission Control. "Competent," he clarified, meant "we will never take anything for granted," never being "found short in our knowledge and in our skills," striving for Mission Control to be "perfect." He instructed his team to write "Tough and Competent" on their blackboards, to "never be erased," serving as a constant reminder of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee, and as the "price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control." This dictum instilled a culture of rigorous accountability, meticulous preparation, and unwavering excellence. Following the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe notably quoted this speech, asserting that these words represent "the price of admission to the ranks of NASA."

4.2. "Failure Is Not an Option" Phrase

Eugene Kranz has become widely associated with the phrase "Failure is not an option," largely due to its prominent use in the 1995 film Apollo 13, where it was uttered by actor Ed Harris in his portrayal of Kranz. Kranz later adopted the phrase as the title of his 2000 autobiography. It subsequently became the title of a 2004 History Channel television documentary about NASA and its 2005 sequel, Beyond the Moon: Failure Is Not an Option 2. Kranz frequently delivers motivational lectures titled "Failure Is Not an Option," often at historical venues like the Apollo 13 flight control room.

However, the phrase was not originally coined by Kranz himself. It was, in fact, created by William Broyles, Jr., one of the screenwriters for Apollo 13. Broyles' inspiration came from a statement made by another member of the Apollo 13 mission control crew, FDO Flight Controller Jerry Bostick. Bostick recounted that when interviewed for the film, he was asked if anyone panicked during the crisis. His reply was: "No, when bad things happened, we just calmly laid out all the options, and failure was not one of them. We never panicked, and we never gave up on finding a solution." Broyles immediately recognized the power of this statement and identified it as the perfect "tag line for the whole movie," ultimately attributing it to the Kranz character in the film. The phrase has since become a powerful symbol of resilience, determination, and innovative problem-solving in the face of extreme adversity.

4.3. The Human Factor and "The Right Stuff"

Kranz believed that the rescue of the Apollo 13 astronauts, despite the mission not achieving its primary objective, served as a prime example of the "human factor" that emerged from the 1960s space race. According to Kranz, this human element was largely responsible for the United States' achievement of landing on the Moon within a single decade. He described this factor as a unique blend of young, intelligent minds, working relentlessly through sheer willpower to produce what he termed "the right stuff."

Kranz articulated his view on the "human factor" by stating that "They were people who were energized by a mission. And these teams were capable of moving right on and doing anything America asked them to do in space." He cited organized examples of this factor in the work of companies like Grumman, which developed the Apollo Lunar Module, North American Aviation, and the Lockheed Corporation. He noted that after the intense period of the 1960s, many of these pioneering companies dissolved through corporate mergers, such as when Lockheed became Lockheed Martin. Another testament to the "human factor" was the ingenuity and hard work displayed by the teams that developed emergency plans and procedures as new, unforeseen problems arose during the critical Apollo 13 mission, highlighting the indispensable role of human creativity and dedication in overcoming complex technological challenges.

4.4. Views on the Space Program

Eugene Kranz held strong views on the evolution of the space program after the conclusion of the Apollo missions, expressing concern that much of the "human factor" he had witnessed seemed to diminish. He attributed this decline partly to the perception that the Moon landings were primarily a short-term goal to surpass the Soviet Union, rather than a sustained commitment to space exploration.

In a spring 2000 interview, when asked if NASA remained the same institution it was during the space race years, Kranz responded, "No. In many ways we have the young people, we have the talent, we have the imagination, we have the technology. But I don't believe we have the leadership and the willingness to accept risk, to achieve great goals." He emphasized the critical need for "a long-term national commitment to explore the universe," asserting it as "an essential investment in the future of our nation - and our beautiful, but environmentally challenged planet."

In his autobiography, Failure Is Not an Option, Kranz openly expressed his disappointment that public and governmental support for space exploration waned significantly after the Apollo program. He outlined his vision for revitalizing the space program, advocating for a rejuvenated NASA. He argued that "Lacking a clear goal the team that placed an American on the Moon, NASA, has become just another federal bureaucracy beset by competing agendas and unable to establish discipline within its structure." While acknowledging NASA's "amazing array of technology and the most talented workforce in history," he contended that it "lacks top-level vision."

Kranz observed that NASA's retreat from the inherent risks of space exploration began after the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster and had intensified over the subsequent decade. He stressed that the NASA Administrator, being a presidential appointee, largely reflects the incumbent President's views on space. He suggested that if space exploration were placed on the national agenda for upcoming elections, a newly elected President would have the opportunity to appoint new, committed top-level NASA leadership willing to rebuild the space agency and reinvigorate America's space program.

5. Personal Life

Eugene Kranz's personal life reflects a committed family man who balanced a demanding and high-stakes career with his private commitments.

5.1. Family

Kranz is a devout Catholic and has six children with his wife, Marta: Carmen (born 1958), Lucy (1959), Joan Frances (1961), Mark (1963), Brigid (1964), and Jean Marie (1966). His youngest daughter, Jeannie, penned an article for NASA titled Lessons from My Father, in which she described her father as a very "engaged" parent. She affectionately compared his parenting style to that of Ward Cleaver, the father figure in the classic television show Leave It to Beaver, highlighting his dedication to his family despite the pressures of his professional life.

6. Honors and Evaluation

Eugene Kranz's distinguished career and profound contributions to human spaceflight have been widely recognized through numerous awards, extensive portrayal in popular culture, and lasting commemorations that underscore his significant influence.

6.1. Awards and Honors

Kranz has received a multitude of awards and honors throughout his career and in retirement, acknowledging his exceptional service and leadership in space exploration:

- American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Lawrence Sperry Award, 1967

- Saint Louis University: Alumni Merit Award, 1968; Founders Award, 1993; Honorary Doctor of Science, 2015

- NASA Exceptional Service Medal, 1969 and 1970

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1970

- Downtown Jaycees of Washington D.C. Arthur S. Fleming Award - recognized as one of ten outstanding young men in government service in 1970

- NASA Distinguished Service Medal, 1970, 1982, and 1988

- NASA Outstanding Leadership Medal, 1973 and 1993

- NASA SES Meritorious Executive, 1980, 1985 and 1992

- American Astronautical Society: AAS Fellow, 1982; Spaceflight Award, 1987

- Robert R. Gilruth Award, 1988, North Galveston County Jaycees

- The National Space Club; Astronautics Engineer of the Year Award, 1992

- Theodore Von Karman Lectureship, 1994

- Recipient of the 1995 History of Aviation Award for the "Safe return of the Apollo 13 Crew," Hawthorne, California

- Honorary Doctor of Engineering Degree from the Milwaukee School of Engineering, 1996

- Louis Bauer Lecturer, Aerospace Medical Association, 2000

- Selected for "2004 and 2006 Gathering of Eagles" honoring Aerospace and Aviation Pioneers at the Air Force Air Command and Staff College, Maxwell AFB, Alabama

- John Glenn Lecture, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, 2005

- Lloyd Nolen, Lifetime Achievement in Aviation Award, 2005

- Wright Brothers Lecture - Wright Patterson AFB, 2006

- NASA Ambassador of Exploration, 2006

- Rotary National Award for Space Achievement's National Space Trophy, 2007

- Air Force ROTC Distinguished Alumni Award, 2014

- National Aviation Hall of Fame, 2015

- Honorary Doctorate of Science from Saint Louis University, 2015

- Great American Award, The All-American Boys Chorus, 2015

- Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) Medal of Honor, 2017

- Vice Admiral Donald D. Engen, U.S. Navy (Ret.), Flight Jacket Night Lecture, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum - National Air and Space Society, November 8, 2018

- Awarded the 2021 Michael Collins Trophy for Lifetime Achievement from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

6.2. Portrayal in Popular Culture

Eugene Kranz's compelling story and iconic image have led to his portrayal in numerous dramatizations of the Apollo program, significantly shaping public perception of space exploration heroes.

He was first depicted in the 1974 TV movie Houston, We've Got a Problem, where he was played by Ed Nelson. His most famous portrayal was by actor Ed Harris in the 1995 film Apollo 13, a role for which Harris received an Oscar nomination. Matt Frewer portrayed him in the 1996 TV movie Apollo 11, and Dan Butler took on the role in the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon. In a 2016 episode titled "Space Race" of the NBC series Timeless, he was played by John Brotherton. In the 2019 Apple TV+ series For All Mankind, Eric Ladin portrays him, with elements of his character featuring fictionalized aspects due to the series' alternate history context. In the video game Kerbal Space Program, the character representing Mission Control is named "Gene Kerman," a clear reference to Kranz, and is depicted wearing a vest similar to his signature apparel.

Kranz has also been featured in several documentaries that utilize NASA film archives, including:

- The 2004 History Channel production Failure Is Not an Option

- Its 2005 follow-up Beyond the Moon: Failure Is Not an Option 2

- Recurring History Channel broadcasts based on the 1979 book The Right Stuff

- The 2008 Discovery Channel production When We Left Earth

- The 2017 David Fairhead documentary Mission Control: The Unsung Heroes of Apollo.

Archived audio clips containing Kranz's name and voice are included in the track "Go!" on the 2015 Public Service Broadcasting album The Race for Space, a track inspired by the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

6.3. Influence and Commemoration

Eugene Kranz's influence extends beyond his direct contributions to spaceflight through lasting commemorations and his continued advocacy. The Eugene Kranz Junior High School, located in Dickinson, Texas, is named in his honor. In 2020, Toledo Express Airport was officially renamed the Eugene F. Kranz Toledo Express Airport, recognizing his roots in Ohio. The establishment of the Gene Kranz Scholarship, aimed at supporting young students in STEM fields, continues his legacy of fostering future generations of innovators.

In a 2010 survey conducted by the Space Foundation, Kranz was ranked as the second most popular space hero, a testament to his indelible mark on public consciousness. His enduring commitment to sharing his experiences and insights through motivational speeches and public appearances continues to inspire, reinforcing his role as an icon of resilience, problem-solving, and the human spirit of exploration.