1. Life

Erich Fromm's life journey, from his early years in Germany to his later academic career and retirement in Switzerland, was marked by deep intellectual engagement and a commitment to understanding human nature and society.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Erich Fromm was born on March 23, 1900, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, as the only child of Rosa (Krause) and Naphtali Fromm. His father, born in 1869, was an Orthodox Jewish and introverted wine merchant who was not particularly successful. His mother was described as energetic, narcissistic, and depressive, contributing to an unhappy childhood for Fromm. A traumatic experience at the age of 12, witnessing the suicide of a talented and beautiful woman he admired, deeply affected him, as she reportedly took her own life due to an unbreakable bond with her father, seeking unity with him in death. Fromm himself wished to be pronounced as "Erich Fromm".

Fromm began his academic studies in 1918 at the University of Frankfurt am Main, initially pursuing jurisprudence for two semesters. In the summer semester of 1919, he transferred to the University of Heidelberg, where he shifted his focus to sociology. At Heidelberg, he studied under influential figures such as Alfred Weber (the brother of sociologist Max Weber), the psychiatrist-philosopher Karl Jaspers, and Heinrich Rickert. Fromm received his Ph.D. in sociology from Heidelberg in 1922, with a dissertation titled "On Jewish Law" (Das jüdische Gesetz. Ein Beitrag zur Soziologie des Diaspora-JudentumsGerman). During this period, Fromm was also actively involved in Zionism, influenced by the religious Zionist rabbi Nehemia Anton Nobel, and participated in Jewish student organizations. However, he soon distanced himself from Zionism, believing it conflicted with his ideal of "universalist Messianism and Humanism."

1.2. Psychoanalytic Training and Early Career

In the mid-1920s, Fromm pursued training as a psychoanalyst at Frieda Reichmann's psychoanalytic sanatorium in Heidelberg. They married in 1926, but separated shortly after and divorced in 1942. Fromm began his own clinical practice in 1927. In 1930, he joined the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, the home of the Frankfurt School, where he completed his psychoanalytical training and further developed his theoretical framework.

1.3. Migration to the United States and Academic Career

With the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany, Fromm, being Jewish, was compelled to leave the country. He initially moved to Geneva, Switzerland, before emigrating to the United States in 1934, settling in New York City. In New York, he joined Columbia University. Fromm became a prominent figure within the Neo-Freudian school of psychoanalytical thought, alongside contemporaries like Karen Horney and Harry Stack Sullivan. Fromm and Horney significantly influenced each other's intellectual development; Horney gained insights into psychoanalysis from Fromm, while he helped her understand sociological concepts. Their intellectual relationship, however, concluded in the late 1930s.

After leaving Columbia, Fromm continued to contribute significantly to the field. In 1943, he helped establish the New York branch of the Washington School of Psychiatry. In 1946, he co-founded the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology. He also held faculty positions at Bennington College from 1941 to 1949 and taught courses at The New School for Social Research in New York from 1941 to 1959.

1.4. Move to Mexico and Later Life

In 1949, Fromm relocated to Mexico City, where he became a professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and established a psychoanalytic section within its medical school. Concurrently, he served as a professor of psychology at Michigan State University from 1957 to 1961 and as an adjunct professor of psychology at the graduate division of Arts and Sciences at New York University after 1962. He continued teaching at UNAM until his retirement in 1965 and at the Mexican Society of Psychoanalysis (SMP) (Instituto Mexicano de PsicoanálisisSpanish) until 1974. Around the 1970s, Fromm and his wife lived in Cuernavaca, Mexico.

In 1974, Fromm moved from Mexico City to Muralto, Switzerland, where he spent his final years. He passed away at his home in Muralto on March 18, 1980, just five days before his eightieth birthday. Throughout his academic career, Fromm maintained his private clinical practice and published a prolific series of influential books. Although he was reportedly an atheist who ceased observing Jewish religious rituals and rejected Zionism, he described his spiritual stance as a form of "nontheistic mysticism."

2. Thought and Theory

Erich Fromm's intellectual contributions are diverse, spanning psychology, sociology, philosophy, and social criticism. His work is characterized by a profound humanism and a critical analysis of modern society, aiming to understand the human condition and advocate for a more humane social order.

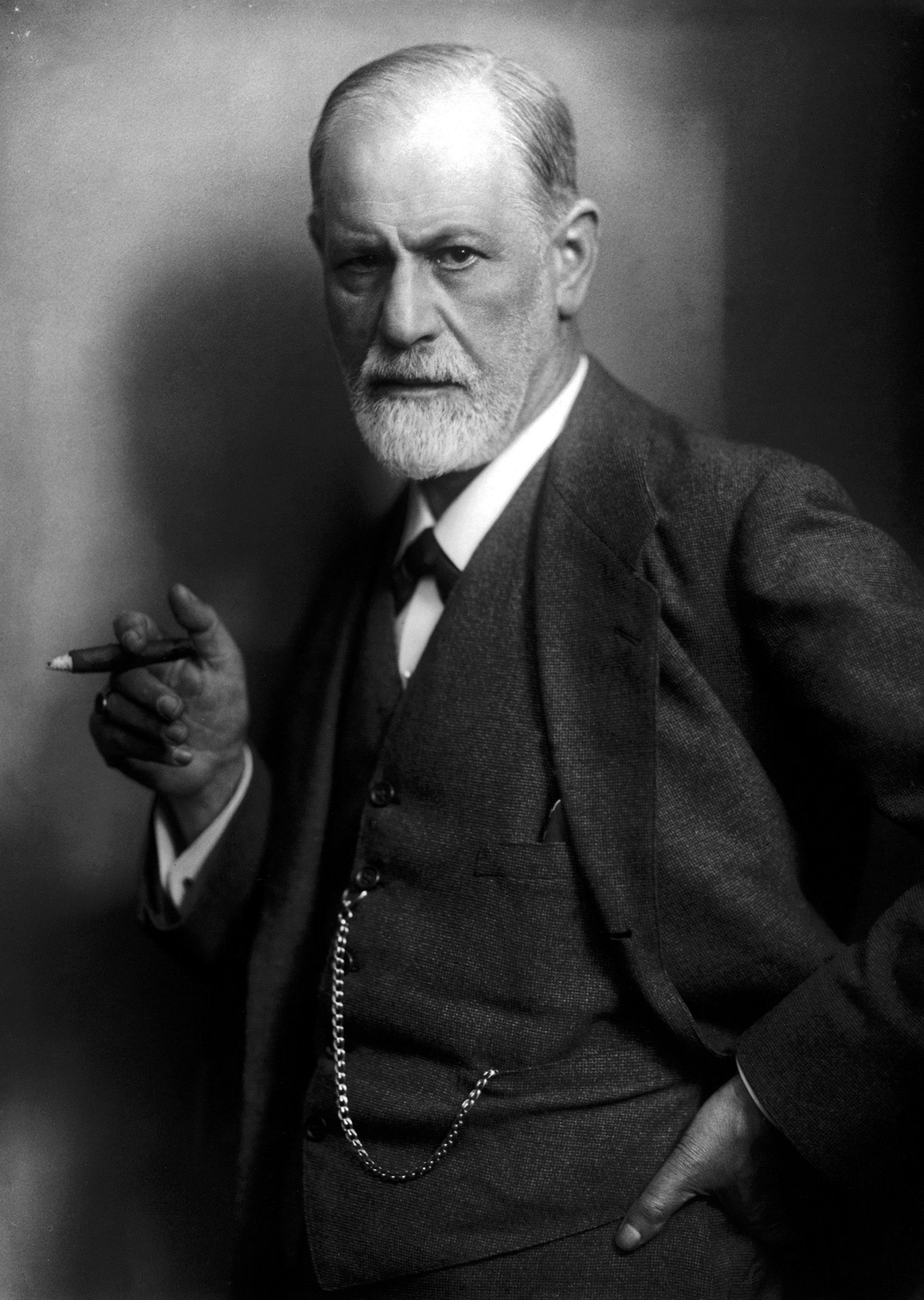

2.1. Critique of Freud

Fromm extensively examined the life and work of Sigmund Freud, acknowledging Freud's foundational impact while also offering significant critiques. He identified a notable discrepancy between Freud's early and later theories of human drives. Before World War I, Freud conceptualized human drives as a tension between desire and repression. However, after the war, Freud shifted his focus to a struggle between biologically universal Life (Eros) and Death (Thanatos) instincts. Fromm criticized Freud and his followers for failing to acknowledge the contradictions between these two theoretical phases.

Fromm also challenged Freud's dualistic thinking, arguing that Freudian descriptions of human consciousness as a struggle between two poles were too narrow and limiting. Furthermore, Fromm condemned Freud for what he perceived as misogyny, suggesting that Freud was unable to transcend the patriarchal environment of early 20th-century Vienna. Despite these criticisms, Fromm held a deep respect for Freud and his achievements. He considered Freud one of the "architects of the modern age," alongside Albert Einstein and Karl Marx, though Fromm emphasized that he regarded Marx as both historically more important and a superior thinker.

2.2. Psychological and Social Psychology

Fromm's psychological theories are deeply intertwined with his social philosophy, exploring how individual psychology is shaped by societal structures and how individuals navigate the challenges of modern existence.

2.2.1. Core Concepts and Major Works

Fromm's seminal works laid the groundwork for his psychological theories, which often blended psychoanalysis with sociology and ethics. His first major work, Escape from Freedom (1941, known in Britain as The Fear of Freedom), is considered a foundational text in political psychology. In this book, Fromm analyzed the psychological origins of fascism and explored how the emergence of individual freedom in modern society could lead to a desire to escape that freedom, resulting in authoritarian tendencies.

His second important work, Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947), further developed these ideas, outlining Fromm's theory of human character as a natural outgrowth of his theory of human nature. These books collectively explored the human urge to seek authority and control when faced with the burdens of freedom. Fromm's most popular book, The Art of Loving (1956), became an international bestseller, reiterating and complementing the principles of human nature discussed in his earlier works.

Central to Fromm's worldview was his interpretation of the Talmud and Hasidic Judaism. He studied Talmud from a young age and later the Tanya by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi. Although he turned away from orthodox Judaism in 1926, he adopted secular interpretations of scriptural ideals. He interpreted the biblical story of Adam and Eve's exile from the Garden of Eden allegorically, viewing their act of eating from the Tree of Knowledge not as a sin but as a virtuous step in human evolution. For Fromm, this act represented humanity's awareness of being separate from nature, leading to existential angst but also enabling the development of love and reason to overcome this disunity.

2.2.2. Character Theory

In Man for Himself, Fromm introduced his theory of "character orientation," distinguishing it from Freud's libido organization. Fromm focused on two fundamental ways individuals relate to the world: "Assimilation" (acquiring and assimilating things) and "Socialization" (reacting to people). He asserted that these orientations are not instinctive but are responses to life's circumstances, and individuals are rarely exclusively one type.

Fromm identified four nonproductive character orientations and one positive, productive orientation:

- Receptive**: Individuals who believe the source of all good is outside themselves and that they can only receive things, not create them.

- Exploitative**: Those who believe they must take what they need or want from others by force or cunning.

- Hoarding**: Individuals who find security in accumulating and keeping things, including emotions, rather than sharing or spending.

- Marketing**: Characterized by treating oneself and others as commodities to be marketed and exchanged, adapting one's personality to fit societal demands. This orientation, arising in modern society, reflects a relativistic ethic where value is determined by market needs.

- Productive**: The positive orientation, characterized by the capacity for love, reason, and productive work. Despite existential struggles, productive individuals realize their potential, engage actively with the world, and strive for self-realization. Fromm believed that the answer to the paradox of human existence-the simultaneous need for closeness and independence-is productiveness.

Fromm's four nonproductive orientations were later validated through psychometric tests, such as The Person Relatedness Test by Elias H. Porter and the LIFO test and Strength Deployment Inventory.

2.2.3. Human Nature and Needs

Fromm posited that humans have fundamental needs that arise from their unique existential situation. He introduced concepts like biophilia (love of life) and necrophilia (love of death) to describe productive and destructive psychological orientations, respectively. Biophilia, for Fromm, represented a productive psychological orientation and a "state of being," encompassing love for humanity, nature, independence, and freedom.

Fromm outlined the following basic human needs:

| Need | Description |

|---|---|

| Transcendence | Humans, thrown into the world without their consent, must transcend their nature by destroying or creating. This can manifest as malignant aggression (killing for reasons other than survival) or as the capacity to create and care for their creations. |

| Rootedness | The need to establish roots and feel at home in the world. Productively, this allows individuals to grow beyond the security of their origins and form ties with the outside world. Nonproductively, it can lead to fixation and fear of moving beyond the security of a mother figure or substitute. |

| Sense of Identity | The drive to establish one's unique sense of self. Nonproductively, this is expressed as conformity to a group; productively, as individuality. |

| Frame of orientation | The need to understand the world and one's place within it, providing a consistent way of perceiving and comprehending reality. |

| Excitation and Stimulation | The need to actively strive for goals and engage with the world, rather than passively responding to stimuli. |

| Unity | A sense of oneness and connection between oneself and the "natural and human world outside." |

| Effectiveness | The need to feel accomplished and to make an impact on the world. |

2.2.4. Love and Relationships

Fromm viewed love not as a fleeting emotion but as an interpersonal creative capacity that requires effort and skill. He distinguished this creative capacity from what he considered various forms of narcissistic neuroses and sado-masochistic tendencies often mistaken for "true love." He argued that the experience of "falling in love" often indicates a failure to grasp the true nature of love, which he believed always comprises four essential elements:

- Care**: Active concern for the life and growth of the loved one.

- Responsibility**: A voluntary response to the needs of another, not a duty.

- Respect**: The ability to see a person as they are, to be aware of their unique individuality, and to desire their growth.

- Knowledge**: Understanding the other person deeply, going beyond superficial appearances to grasp their core being.

Drawing from the Torah, Fromm cited the story of Jonah, who did not wish to save the residents of Nineveh, as an example of how the qualities of care and responsibility are often absent in human relationships. He also asserted that few people in modern society truly possess respect for the autonomy of others or objective knowledge of their genuine needs.

2.2.5. Freedom and Escape Mechanisms

A central theme in Fromm's work is the human relationship with freedom. He believed that freedom is an inherent aspect of human nature that individuals either embrace or attempt to escape. Embracing one's freedom of will is psychologically healthy, whereas escaping freedom through various mechanisms is a root cause of psychological conflict. Fromm outlined three common escape mechanisms:

- Automaton conformity**: Individuals change their ideal self to conform to societal expectations, thereby losing their true self. This displaces the burden of choice from the individual to society.

- Authoritarianism**: Involves giving control of oneself to another person or entity. By submitting one's freedom, this act almost entirely removes the burden of choice.

- Destructiveness**: Any process that attempts to eliminate others or the world as a whole, serving as a desperate attempt to escape the overwhelming burden of freedom. Fromm stated that "the destruction of the world is the last, almost desperate attempt to save myself from being crushed by it."

Fromm's thesis of the "escape from freedom" highlights the paradox of modern existence, where individuals, freed from traditional "primary ties" (such as nature or family), find this newfound freedom an unbearable burden. If economic, social, and political conditions do not offer a basis for the realization of individuality, while at the same time people have lost those ties which gave them security, this lag makes freedom an unbearable burden. It then becomes identical with doubt, with a kind of life which lacks meaning and direction. Powerful tendencies arise to escape from this kind of freedom into submission or some kind of relationship to man and the world which promises relief from uncertainty, even if it deprives the individual of his freedom.

2.2.6. Human Destructiveness

Fromm extensively explored the nature of human destructiveness, particularly in his work The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness. He argued against the Freudian idea of a universal death instinct, instead positing that human aggression is not always instinctual or phylogenetically programmed. While influenced by Konrad Lorenz's book On Aggression, Fromm asserted that not all creativity is constructive; some forms, like the creation of bombs, are inherently destructive, harming humanity itself. He distinguished between benign aggression (defensive, serving survival) and malignant aggression (cruelty, sadism, necrophilia), which is uniquely human and not serving biological survival.

2.3. Social Philosophy and Criticism

Fromm's social philosophy is characterized by a sharp critique of societal structures that he believed hinder human potential and foster alienation. He advocated for social systems that promote humanistic values and democratic principles.

2.3.1. Alienation

Erich Fromm introduced the concept of alienation (keterasinganIndonesian) to describe a pervasive human experience in modern society. He believed that individuals become alienated in a technological and rationalized society, leading them to feel like strangers to themselves. This alienation stems from a system where humans no longer perceive themselves as the center of the world, and their actions are not seen as their own creations but rather as something to be obeyed or even worshipped. Fromm argued that this alienation permeates nearly all aspects of human life, including one's relationship with oneself, with others, with food, with work, and even with the state. This condition is also caused by humanity's inability to fulfill its fundamental human needs.

2.3.2. Social Character

Fromm's theory of social character describes a shared psychological framework that shapes individuals' behavior and adaptation within specific societal contexts. He viewed social character as a system for channeling life energy (élan vitalFrench) and satisfying material needs through positive relationships with others and adaptation to nature. According to Fromm, social character is a coherent system where individual traits are interconnected, meaning a change in a single trait can only occur if the entire system undergoes transformation. This system serves as a fundamental guide for behavior, differentiating individuals while sharing common physiological bases.

2.3.3. Critique of Societal Systems

Fromm's social criticism extended to various societal systems that he believed inhibited human potential and fostered alienation. He was a vocal critic of capitalism and authoritarianism. In Escape from Freedom, Fromm even found a certain value in medieval feudalism due to its lack of individual freedom, rigid structure, and clear obligations, which provided a sense of belonging and meaning, reducing the burden of choice and competition.

Fromm's critique of the modern political and capitalist order led him to advocate for a more humane society. He rejected both Western capitalism and Soviet communism, viewing both as dehumanizing systems that contributed to the widespread modern phenomenon of alienation.

2.3.4. Humanism and Democratic Socialism

The culmination of Fromm's social and political philosophy was his 1955 book, The Sane Society, in which he argued for a humanistic and democratic socialism. Building on the early works of Karl Marx, Fromm sought to re-emphasize the ideal of freedom, which he felt was often missing from Soviet Marxism and more prevalent in the writings of libertarian socialists and liberal theorists. He became a co-founder of socialist humanism, actively promoting Marx's early writings and their humanist messages to the public in the U.S. and Western Europe. He also participated in a Christian-Marxist intellectual dialogue group in 1960s Czechoslovakia.

In the early 1960s, Fromm published works like Marx's Concept of Man and Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx and Freud, aiming to correct misunderstandings of Marxism. In 1965, to foster cooperation between Marxist humanists in the West and East, he edited Socialist Humanism: An International Symposium. His contributions were recognized when the American Humanist Association named him Humanist of the Year in 1966. He also received the Nelly Sachs Prize in 1979.

Fromm was also actively involved in U.S. politics. He joined the Socialist Party of America in the mid-1950s, seeking to provide an alternative viewpoint to McCarthyism. His paper May Man Prevail? An Inquiry into the Facts and Fictions of Foreign Policy (1961) articulated this perspective. As a co-founder of SANE, Fromm's strongest political activism was in the international peace movement, where he campaigned against the nuclear arms race and U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. After supporting Senator Eugene McCarthy's unsuccessful bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968, Fromm largely withdrew from the American political scene, though he did write Remarks on the Policy of Détente for a U.S. Senate hearing in 1974.

2.4. Religion and Spirituality

Fromm believed that all humans possess a fundamental need for religion, which he defined as the need for an object of worship that provides a frame of orientation. In this context, he emphasized that love should serve as the framework for humanity's understanding of religion, asserting that humans are inherently religious beings.

Fromm's personal spiritual stance is often described as a form of "non-theistic mysticism," reflecting his complex intellectual background in sociology, psychology, and philosophy. In his 1966 work, You Shall Be as Gods: A Radical Interpretation of the Old Testament and Its Tradition, Fromm explored the concept of God in the Jewish tradition of the Old Testament. He identified four shifts in the understanding of God within these texts: from an omnipotent God to a constitutionally powerful God who adheres to His own principles, then to a nameless God, and finally to a God entirely devoid of essential attributes.

2.5. Educational Philosophy

Erich Fromm held a humanistic view of character education. He posited that character is an unfinished spiritual condition, capable of transformation. Its development and quality are shaped by the social processes that define an individual's environment and identity. He believed that healthy character development involves individuals working productively in accordance with social demands and participating in social life with a sense of love. A healthy personality, for Fromm, is characterized by a productive individual who can develop their potential, show love and compassion, possess imagination, and maintain a strong sense of self-awareness.

3. Major Works

Erich Fromm was a prolific writer whose works significantly influenced social psychology, psychoanalysis, and humanistic philosophy.

- Das jüdische Gesetz. Ein Beitrag zur Soziologie des Diaspora-Judentums (1922)

- Über Methode und Aufgaben einer analytischen Sozialpsychologie (1932)

- Die psychoanalytische Charakterologie und ihre Bedeutung für die Sozialpsychologie (1932)

- Sozialpsychologischer Teil. In: Studien über Autorität und Familie (1936)

- Zweite Abteilung: Erhebungen (1936)

- Die Furcht vor der Freiheit (1941)

- Psychoanalyse & Ethik (1946)

- Psychoanalyse & Religion (1949)

- Escape from Freedom (US), The Fear of Freedom (UK) (1941): This seminal work analyzes the psychological origins of fascism and explores how the burdens of modern freedom can lead individuals to seek escape through submission to authoritarian systems. It is considered a foundational text in political psychology.

- Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947): Building on Escape from Freedom, this book delves into Fromm's theory of human character and his humanistic ethical framework, emphasizing the importance of productive living for human well-being.

- The Forgotten Language: An Introduction to the Understanding of Dreams, Fairy Tales, and Myths (1951)

- The Sane Society (1955): In this work, Fromm critiques modern industrial societies, particularly capitalism and communism, arguing that they foster alienation and inhibit human potential. He advocates for a humanistic and democratic socialism as a path to a more mentally healthy and fulfilling society.

- The Art of Loving (1956): An international bestseller, this book explores love not as a passive emotion but as an active, creative capacity that requires knowledge, care, responsibility, and respect. It offers a guide to developing the capacity for true love in all its forms.

- Sigmund Freud's Mission: An Analysis of his Personality and Influence (1959)

- Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis (1960)

- May Man Prevail? An Inquiry into the Facts and Fictions of Foreign Policy (1961)

- Marx's Concept of Man (1961): Fromm reinterprets Marx's early philosophical writings, emphasizing their humanistic and ethical dimensions, often overlooked in later, more dogmatic interpretations of Marxism.

- Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx and Freud (1962)

- The Dogma of Christ and Other Essays on Religion, Psychology and Culture (1963)

- The Heart of Man: Its Genius for Good and Evil (1964)

- Socialist Humanism: An International Symposium (editor) (1965)

- You Shall Be as Gods: A Radical Interpretation of the Old Testament and Its Tradition (1966): This book, published in New York, explores Fromm's unique interpretation of the Old Testament, particularly the evolving concept of God within Jewish tradition, highlighting its humanistic implications.

- The Revolution of Hope: Toward a Humanized Technology (1968)

- The Nature of Man (1968)

- The Crisis of Psychoanalysis: Essays on Freud, Marx and Social Psychology (1970)

- Social Character in a Mexican Village: A Sociopsychoanalytic Study (with Michael Maccoby) (1970)

- The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973): This comprehensive study examines the roots and manifestations of human aggression and violence, distinguishing between benign and malignant forms of destructiveness.

- To Have or to Be? (1976): In his later work, Fromm contrasts two fundamental modes of existence: the "having" mode, focused on material possessions and consumption, and the "being" mode, centered on experience, growth, and genuine human connection. He argues for a shift towards the "being" mode for individual and societal well-being.

- Greatness and Limitation of Freud's Thought (1979)

- On Disobedience and Other Essays (1981)

- The Working Class in Weimar Germany: A Psychological and Sociological Study (1984)

- For the Love of Life (1986)

- The Revision of Psychoanalysis (1992)

- The Art of Being (1993)

- The Art of Listening (1994): Published posthumously, this work compiles Fromm's insights on the importance of deep, empathetic listening in psychoanalysis and human relationships.

- On Being Human (1994)

- The Essential Erich Fromm: Life Between Being and Having (1995)

- Love, Sexuality, and Matriarchy: About Gender (1997)

- The Erich Fromm Reader (1999)

- Beyond Freud: From Individual to Social Psychoanalysis (2010)

- The Pathology of Normalcy (2010)

4. Influence and Evaluation

Fromm's intellectual legacy is profound, extending across various disciplines and influencing subsequent generations of thinkers.

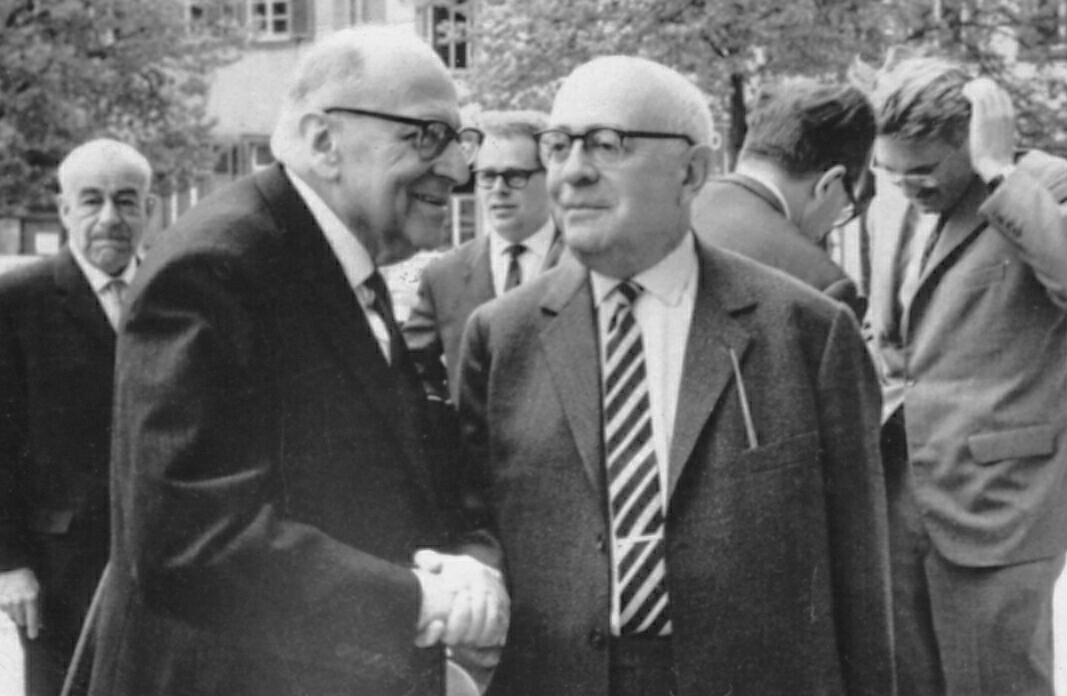

4.1. Relationship with the Frankfurt School

Fromm was a significant member of the Frankfurt School, a group of thinkers associated with the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research. His work contributed to the development of critical theory by integrating psychoanalysis with Marxism and social critique. He introduced psychoanalytic insights to the Frankfurt School, explaining how psychological factors contribute to societal realities and the loss of critical consciousness among the proletariat. Fromm's intellectual standing within the Frankfurt School is often equated with that of other prominent figures like Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, and Jürgen Habermas. His cross-disciplinary approach, combining philosophy, sociology, and psychoanalysis, allowed him to generate creative ideas about human values and the future of humanity. He also collaborated with members of the Frankfurt School on works such as The Authoritarian Personality.

4.2. Influence on Later Thinkers

Fromm's humanistic insights, social criticism, and psychoanalytic perspectives have influenced numerous scholars across various disciplines. His character orientations, particularly the four nonproductive types, served as the basis for psychometric tests such as The Person Relatedness Test by Elias H. Porter in collaboration with Carl Rogers, and later the LIFO test and the Strength Deployment Inventory. Fromm also influenced his student Sally L. Smith, who went on to found the Lab School of Washington and the Baltimore Lab School, institutions focused on educational approaches for children with learning differences.

4.3. Overall Assessment

Erich Fromm's work remains highly relevant for understanding contemporary social and psychological issues. His emphasis on human freedom, the dangers of alienation, and the importance of love and productive living offers a powerful critique of dehumanizing societal systems and a vision for a more humane future. His ability to synthesize complex ideas from diverse fields like psychoanalysis, sociology, and philosophy continues to provide valuable frameworks for analyzing individual and collective well-being in a rapidly changing world.

5. Criticism

Despite his widespread influence, Erich Fromm's theories and ideas have drawn criticism from prominent contemporaries.

Herbert Marcuse, in his work Eros and Civilization, criticized Fromm, suggesting that Fromm, initially a radical theorist, later became too conformist. Marcuse argued that Fromm, along with his colleagues Harry Stack Sullivan and Karen Horney, removed Freud's libido theory and other radical concepts, thereby reducing psychoanalysis to a set of idealist ethics that merely embraced the status quo. Fromm, in response (notably in The Sane Society and The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness), argued that while Freud deserved credit for recognizing the unconscious, he tended to reify his concepts, depicting the self as a passive outcome of instinct and social control, with minimal volition. Fromm contended that later scholars like Marcuse accepted these concepts as dogma, whereas social psychology requires a more dynamic theoretical and empirical approach.

In reference to Fromm's leftist political activism as a public intellectual, Noam Chomsky stated, "I liked Fromm's attitudes but thought his work was pretty superficial."

6. Related Topics

Fromm's work is connected to a wide array of concepts, figures, and academic fields that provide context for his intellectual contributions.

6.1. Key Concepts

- Alienation

- Authoritarianism

- Biophilia

- Character orientation

- Critical theory

- Democratic socialism

- Existentialism

- Humanism

- Necrophilia

- Psychoanalysis

- Social character

- Social psychology

- Unconscious mind

6.2. Associated Figures

- Theodor W. Adorno

- Max Horkheimer

- Karen Horney

- Karl Jaspers

- Carl Jung

- Konrad Lorenz

- Herbert Marcuse

- Karl Marx

- Frieda Reichmann

- Heinrich Rickert

- Carl Rogers

- Alfred Weber

- Max Weber